Have you ever tried to introduce diabetes to a newly diagnosed patient and found yourself at a loss? Do you stumble trying to explain the difference between type 1 and type 2 diabetes? Are you frustrated by the disconnect between your own understanding of diabetes and your ability to explain it? You are not alone! Diabetes educators specialize in the management of diabetes and effectively teaching it to patients.

As a healthcare professional you have learned the basics of diabetes mellitus, but not how to teach a patient who lives with it. Simplifying pathophysiology, medication usage, blood glucose monitoring, meal planning, and overall management of the disease is daunting but it is a skill you can acquire with practice. Teaching patients to take their prescribed medications correctly may be as important as the medication itself because, without a good understanding, patients may take it incorrectly, with poor outcomes.

Studies confirm positive behavioral and economic outcomes of outpatient diabetes education programs on self-care (Brown, 1990). Patients with diabetes who have received diabetes education have better A1C glycosylated hemoglobin levels, fewer emergency department (ED) visits, and better overall health compared to those with diabetes who never received education. Clearly diabetes education matters.

The Need for Diabetes Educators

With over 29.1 million Americans—9.3% of the United States population—diagnosed with diabetes and another 86 million with prediabetes, there are a lot of people needing diabetes education (ADA, 2014). Diabetes is steadily increasing in incidence and prevalence in the United States and remains the seventh leading or contributing cause of death; further, it represents almost 26% of adults age 65 and older, which is 1 out of every 4 elders.

Diabetes in youth age 20 and under has also continued to rise, to 208,000 Americans compared to approximately 23,500 in 2008. Overweight and obesity trends and an aging population have been identified as risk factors causing the growing “diabesity” epidemic in our country. Almost 50% of all Americans are overweight or obese. Clearly a lot of people need your professional knowledge for health education, prevention, treatment, and management of diabetes. It’s a sad truth, but with the climbing rates of diabetes and obesity and projected trends, those who teach patients with diabetes have job security!

Most people with diabetes hear about the disease initially from a healthcare professional, and yet many people with diabetes leave more confused after being given the startling diagnosis because of the heavy use of medical jargon and the complicated information. Being able to simplify diabetes education and meet the learning needs of your patient can make the difference between patients who leave feeling empowered to take control of their diabetes or feeling overwhelmed, depressed, and inclined toward noncompliance.

Although there is plenty of information available via the Internet for anyone to learn about diabetes, most people need the help of a healthcare professional to decipher the information. Referring patients to www.diabetes.org is a great resource of the American Diabetes Association, but it is not enough. You are still needed to help guide your patients through the vast resources on diabetes.

Describing Diabetes Mellitus

A quick review of diabetes mellitus will give you confidence when you are needed to help a newly diagnosed patient cope with this sometimes overwhelming diagnosis.

What Is This Disease?

Knowing more about diabetes, and how to teach your patients about it, will put you in a position to answer the question “What is diabetes mellitus?” Diabetes mellitus has formally been defined by the American Diabetes Association as “a group of metabolic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from defects in the insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. The chronic hyperglycemia of diabetes is associated with long-term macro- and microvascular damage, dysfunction, and failure of various organs, especially the eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart, and blood vessels” (ADA, 2011).

Although that is a correct medical definition, it can be frightening and unintelligible to a patient who may still be in disbelief about having diabetes. Being able to simplify the definition to “Diabetes means your body doesn’t use your food effectively” makes more sense to most people.

Diabetes was recognized as a medical problem over 2000 years ago in Greek writings, so it is not a new disease. It wasn’t until the early 1900s, however, that insulin was identified as the hormone that controls blood sugar levels. Early scientists removed the pancreas from a dog, thus creating a diabetic dog, which helped them confirm that the pancreas produces insulin from beta cells within the islets of Langerhans. In 1921 insulin was finally purified for human injection by Eli Lilly, an early pharmaceutical company, which began the treatment to save lives for type 1 diabetics who produced no insulin.

What Is the Disease Process?

Without insulin, the food we eat, broken down into simple forms of glucose, can’t enter the cells of the body and remains in the bloodstream. After a meal, glucose levels in the body rise, which triggers insulin to be released from the beta cells of the pancreas. Glucose levels in the blood fall as glucose moves into the cells, where it is used for energy production to fuel the body. Extra glucose in the blood can be stored in fat and skeletal muscle tissue. Glucose stored in the liver becomes glycogen.

An opposing hormone, glucagon, has the opposite effect of insulin, resulting in elevated levels of glucose in the blood, where it can be sent for energy throughout the body. The perfect balance of insulin and glucagon production keeps our blood sugar levels regulated between 60 and 100 mg/dL in a fasting state and 100 to <140 mg/dl 2 hours after a meal.

When the body doesn’t produce any insulin (type 1 diabetes) or has a sluggish or resistant response to insulin (type 2 diabetes), chronic hyperglycemia develops; this is known as diabetes mellitus. The term diabetes means “to siphon through,” which refers to the loss of urine as the body attempts to rid itself of the excess glucose and pulls water along with it. The term mellitus was added years later; it means “sweet” or “honey,” referring to the glucose in the urine.

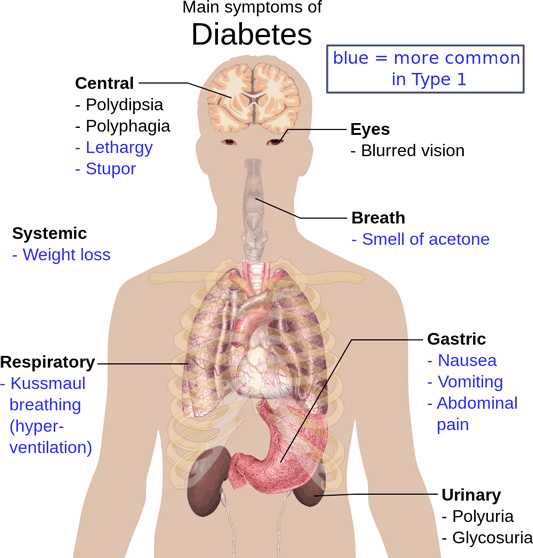

Source: Mikael Häggström, 2014. Wikimedia Commons.

Types of Diabetes

The pathology that causes each type of diabetes is different, and it is important for a patient to understand the medical management for their particular type of diabetes. In type 1 diabetes (the term now used instead of the older term juvenile diabetes), the body stops producing insulin completely. This has been linked to an autoimmune response and occurs mostly in children, representing only 5% to 10% of all people with diabetes.

People with type 1 diabetes have to take insulin injections or they will die, as their brain and body cells starve without the needed glucose. The body can use protein and fat for fuel but the ketones from metabolizing these fuels can create acidosis and become toxic to the body, leading to death. The discovery of insulin through injections has saved millions of lives.

Type 2 diabetes, representing 90% to 95% of all people with diabetes, stems from cellular insulin resistance, or sluggish insulin production, and is generally found in adults. Insulin resistance has a genetic risk and is often found in people who are overweight or obese. Type 2 diabetes can generally be treated with weight loss, meal planning, and exercise because the onset is related to overweight and obesity in 75% of diabetic patients. If lifestyle modifications don’t help, then medication management is added.

Differences Between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes | |

|---|---|

Type 1 Diabetes | Type 2 Diabetes |

Symptoms usually start in childhood or young adulthood. People often seek medical help, because they are seriously ill from sudden symptoms of high blood sugar. | The person may not have symptoms before diagnosis. Usually the disease is discovered in adulthood, but an increasing number of children are being diagnosed with the disease. |

Episodes of low blood sugar level (hypoglycemia) are common. | There are no episodes of low blood sugar level, unless the person is taking insulin or certain diabetes medicines. |

Cannot be prevented. | Can be prevented or delayed with a healthy lifestyle, including maintaining a healthy weight, eating sensibly, and exercising regularly. |

In the past decades the only medications available were insulin and a single class of antihyperglycemics called sulfonylureas. Today more than eight classes have been created, making medication management more complex. People often think incorrectly that if you take insulin you have type 1 diabetes and if you could manage blood sugar levels with a pill you have type 2 diabetes. Research has added significantly to our understanding of the pathophysiology, and type 2 diabetes involves more organs than just the pancreas. Some patients with type 2 may eventually require insulin injections due to pancreatic fatigue and the duration of the disease.

The third class of diabetes is gestational diabetes and it results when hyperglycemia is first manifest during pregnancy. Many pregnant women with diabetes can control blood sugars by careful food planning and avoidance of simple sugars during pregnancy, however some may require insulin injections just for the duration of the pregnancy. Gestational diabetes only occurs in about 2% to 5% of all pregnancies. Unfortunately, a women with gestational diabetes may be at 4 to 6 times greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life.

The problem with hyperglycemia during pregnancy is potentially the large growth of the baby, who has been used to high volumes of glucose during gestation, and delivery complications for the mother. Generally, after the baby is born the mother’s blood glucose stabilizes and she will no longer need insulin. The baby, who had been so used to hyperglycemia in utero, does run the risk of dropping into hypoglycemia after birth and must be monitored until stable.

A fourth class of diabetes is “other,” and it includes endocrinopathies, mature onset diabetes of the young (MODY), and latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult (LADA, or diabetes 1.5). The pathophysiology of each varies and is related to genetic problems, hormone imbalance, and autoimmune destruction of beta cells. The “other” category also includes prediabetes and impaired fasting glucose (IFG).

Both prediabetes and IFG are precursors to diabetes and deserve increased attention by healthcare professionals to avoid chronic hyperglycemia and complications. Each class of diabetes requires different medication management based on the unique needs of the individual.

Knowing what kind of diabetes patients have been diagnosed with is important so you can help them understand specifically what is happening within their own body. The more informed you are about patients’ type of diabetes the better you can anticipate problems they may experience and develop a plan for prevention. By teaching them about symptoms of complications you can help identify problems earlier and get appropriate treatment sooner.

Using common analogies to explain the pathophysiology also can be helpful. Many diabetes educators use the comparison of insulin in the body like a lock (a body cell) and key (the insulin). A patient with type 1 diabetes no longer has the key (insulin) to open the door (the body cell) and food (glucose) cannot be used. The cell ends up starving and suffers damage even if the person eats food.

Even children with type 1 diabetes can understand the analogy of a “diabetic car.” A type 1 diabetic car has no insulin (key) to open the gas tank so the tank stays empty, with no fuel for energy. Without being able to open the lid, a meal is eaten but no gas enters the tank and the car doesn’t function correctly. An outside key must be used (insulin injection) to open the tank and fill it with gas (food). A type 2 car is able to receive some gas, however a lot of it spills on the outside of the car leaving noticeably high gas levels (glucose levels) outside the tank.

Using analogies, comparisons, and simple common terms and objects that people are familiar with can help them understand the complicated diabetes pathophysiology. Approaching patient education in simple terms can be less scary for both you and the patient. Many pharmaceutical companies involved in diabetes products and education have wonderful pictures, diagrams, and other resources to help teach the basic anatomy and physiology of food metabolism and diabetes (see Resources at the end of the course).

Clinical Scenario

Mr. Johnson wonders why he now has to take four insulin injections each day for his diabetes when he used to take a pill only twice daily.

Q: What questions would you ask Mr. Johnson to help him understand the medical management for his diabetes?

A: Examples could include:

- How long have you had diabetes?

- Tell me what you understand causes diabetes?

- Did you try weight loss, exercise, and meal management?

- What do you understand about insulin?

Overcoming Barriers to Effective Teaching

Many barriers prevent healthcare professionals from teaching effectively, or even at all. The first barrier is the fear of inadequate knowledge about the disease. Some don’t know all the facts about diabetes and feel embarrassed to admit it in front of a patient, so they just omit the teaching. You do not have to be a certified diabetes educator (CDE) to teach patients about diabetes. Healthcare professionals who teach about diabetes include lay health workers, health aids, medical assistants, nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, social workers, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certified diabetes educators.

Clearly knowledge is needed before you can teach, however research confirms the adage that people care more about how much you care and not just how much you know (Ciechanowski, 2001;Brown, 1990). Creating relationships of trust, non-judgment, and emotional safety are foundational for effective teaching.

Barriers to teaching also include poor communication, lack of time, low priority in acute settings, low or no reimbursement for teaching, low resources, and low interest from the patient; yet making sure the information is correct and correctly understood are critical to good patient outcomes. Overcoming these barriers has been the quest of the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE), and the organization is a wonderful resource for content, study guides, and even lesson plans for teaching (www.diabeteseducator.org).

Strategies to overcome barriers of poor communication begin with simplifying medical jargon. Healthcare professionals speak in medical (often Latin) vocabulary that can be confusing to patients. A persisting legend tells that a physician teaching a patient to inject insulin used an orange for practice. After having the patient return-demonstrate how to draw up and inject the insulin into the orange, the physician felt confident that the patient understood. Weeks later ,when the patient returned for a followup appointment, the patient’s blood glucose levels remained extremely high. Puzzled, the physician asked the patient if he was still taking the insulin injections as instructed. “Of course,” declared the patient. “But I don’t understand how injecting it into the orange is going to help my diabetes.”

Clearly, we often make assumptions about what the patient understands and forget we may speak a different language! Try to simplify the vocabulary you use as you discuss pathophysiology and other diabetes topics. Instead of saying “insulin resistant,” you could say “Your muscles don’t use the insulin you may be producing.” Instead of metabolic acidosis, you could say “When the body has too much sugar and no insulin it creates a state of too much acid, which makes the body sick.”

For communication barriers related to foreign language, it is important to have a professional translator or use pamphlets and instructional material in the native tongue of the patient. Many credible online sources, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH), provide a large library of free patient education materials in Spanish, Tagalog, and many other foreign languages.

Remember, second-language learners who are conversant in English may still be unfamiliar with slang words common to native English speakers. Phrases such as “fast-food” and “eat and run” may be confusing. Clarify terms and confirm understanding periodically during a teaching session to avoid undesirable outcomes. Click this link for more information.

Another barrier to effective communication has been the approach, often perceived as condescending, when the goal was getting a patient to “comply” with a medical plan of care. Compliance and adherence have always been legitimate issues of concern for healthcare professionals. In the past, educators were often sent to “set the patient straight” or use scare tactics to get a patient to adhere to the prescribed management regimen.

Traditional approaches to patient education have been disease-oriented and based on compliance. If patients disagreed with a plan of care, couldn’t afford the medications, or wanted to try alternative therapies, they were often seen as noncompliant. Good patient outcomes suffered if patients felt judged or dismissed. A useful strategy to overcome this barrier is for healthcare professionals to take on the role of health coaches instead of health dictators. Creating a partnership with the patient improves health outcomes.

The barriers of lack of time, low priority in acute settings, low or no reimbursement for teaching, low resources, and low interest from the patient can also be overcome. Time for diabetic teaching can be found in regular interactions with patients. Every interaction with a person who has diabetes can help educate the patient without making it a formal session. Giving patients their regular insulin dose in a hospital provides a few minutes for assessing their understanding of the purpose and action of the medication. Testing a patient’s blood sugar also creates a space for purposeful conversation.

You may not have the luxury of a half-hour teaching appointment, but can provide a few minutes of teaching during regular interactions of care throughout a shift or home visit. In the acute care setting, diabetes education is often delayed; however, it should be offered after the urgent medical problem has been addressed and the patient is stabilized.

Patients are often more interested in learning how to avoid a hypoglycemic episode or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) once they have experienced the emergency. As the saying goes, “When the student is ready, the teacher appears.” Lack of time is often cited as an excuse. A strategy to overcome that barrier is leaving a simple pamphlet or note with contact information for future diabetes education when the patient may be ready.

After years of lobbying by the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE), using persuasive research to prove the benefits of diabetic education, reimbursement is now available and diabetes education is paid for by most insurance companies. Free resources for diabetes education are exploding in availability. A simple search on the Internet for the word diabetes will quickly produce over 250 million links! Healthcare professionals can feel relieved that, even if their patient education time is limited, learning can continue via reputable online sites. Asking the patient if they are interested in free diabetes education may pique their interest in personally searching the Internet if they have computer skills (also see Resources at the end of this course).

Clinical Scenario

Mrs. Sanchez, a patient with type 2 diabetes who has limited English-speaking skill, keeps missing her diabetes education appointment because she “doesn’t have transportation” but she does have medical insurance.

Q: What strategies could you use to overcome barriers to her receiving diabetes education?

A: Identify alternative transportation for her. Provide Spanish literature through the mail. Find resources within her neighborhood for diabetes education. Inquire if she has access to a computer and the Internet. Provide education on the phone with a translator. Find her diabetes classes in Spanish.

Patient Centered Diabetes Education

Traditional patient education models focused on disease-oriented patient education (DOPE) and were physician centered. Newer models are known as health-oriented patient education (HOPE) and include empowerment strategies that place the patient rather than the physician at the center; this strategy sees the patient as a partner in decision making. Based on adult learning theory, psychodynamic motivational theories, and the Chronic Care Model, diabetes educators now focus on strategies that help patients help themselves.

The goal of diabetes education is to help patients manage their own chronic disease with the resources of a team of healthcare professionals supporting them. The role of the diabetes educator has changed from “sage on stage” to “guide on the side.” Effective diabetes education begins with a paradigm shift to a role as health coach and often cheerleader instead of professional laying down orders for the patient to follow.

Each patient should have a partnership role in making medical decisions. That means patient education must be customized to meet the individual’s needs and include the patient’s goals and desires. Instead of a diabetes educator simply writing a patient’s diet and exercise plan, an effective diabetes educator needs to assess the patient’s goals, abilities, barriers, interests, and resources and develop a goal plan together. Adherence improves because patients are working toward their own goals and not those dictated to them.

ASSURE Mnemonic for Teaching

A diabetes educator can ensure effective education by following the activities in the acronym ASSURE.

ASSURE effective education

- A Analyze the learner

- S State the objectives

- S Select appropriate teaching methods

- U Use effective instructional materials

- R Require learner performance

- E Evaluate the learning

Analyze the Learner

“Analyze the learner” means looking at the patient’s language ability, age, ethnicity, food preferences, gender, and learning style. People of different ages learn differently. We don’t teach a child or adolescent the same way we teach adults. Children need concrete examples to which they can relate, and do well with role play and games, for example. Adults can generally learn by references and analogies. Geriatric patients may need a different approach based on physical limitations such as hearing or vision.

It is essential to confirm English-speaking ability, literacy, and ability to understand written information. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, a national literacy survey found 23% of our adult population lack adequate literacy skills and may not read above a fifth-grade level (National Institute of Literacy, 2013; NCES, 2002). When presenting material to patients in written form, look for simply worded phrases and the inclusion of illustrations that can be understood easily across language and literacy levels. Asking about formal education completed can also help guide you in what level of literature would be appropriate for the person.

When teaching about food choices and meal planning for diabetes management, avoid assumptions about foods. Assuming everyone eats cereal for breakfast, or that breakfast is even in the morning when some people work night shift, can impact medications taken with food. Ethnicity may also impact how learners understands diet planning based on their background, preferred first language, values, and even associations with ethnic foods.

Do not assume people who “look like you” are the same as you! With the growing diversity in our country, people come from a large variety of backgrounds with cultural norms that impact their health; these may include food preferences and even adoption of complementary and alternative therapies. Simply asking people open-ended questions like “What do you typically eat for daily meals?” will provide valuable information to help you guide them toward healthier choices. Long gone are the days when we would give the same standardized ADA 1800-calorie diet handout to everyone. The patient often threw away the seemingly irrelevant pamphlet.

Effectively teaching someone with diabetes about meal planning and food choices must be customized based on food and cooking preferences and resources. Suggesting all patients buy organic produce may be scientifically sound, however not realistic for those on limited budgets or because organic stores may not be near them. Getting a 24-hour or even 3- to 7-day diet history will give you a better idea of what the patient generally eats and prefers in a typical week. Then dietary suggestions for improvement can be made based on tastes, budget, and schedule.

Basic Styles of Learning

Source: Feberal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, 2011.

Gender differences are important to consider when teaching a patient about healthcare needs and management of a chronic disease. Women are generally motivated by social relationships and may thrive in a group class. Men, however, are often motivated by task completion and may prefer a one-to-one teaching session so they can be finished and leave. Research shows that male brains are more developed in motor and spatial skills whereas female brains are more developed in verbal and social thinking (Lewis, 2013). Men may prefer to see graphs, charts, and statistics about the disease whereas women may prefer to learn how it will impact their daily life. Of course there is plenty of variation between the genders but the fact remains that education needs to be customized to meet the patient’s preferences.

Descriptions of the Basic Learning Styles | |

|---|---|

Visual

| Auditory

|

Read and Write

| Kinesthetic

|

Learning styles also impact how a person learns. Generally people can learn through all the methods shown above, and teachers should include a variety of teaching approaches; however, often people have a preferred method. There are online tests to help you identify your own learning style preference. It’s unrealistic to have every patient take a learning styles preference test before you plan your approach to fit their needs; however, you can assess their style through good questioning.

You can ask them how they prefer to learn new information: by reading, watching a video, seeing a demonstration, or learning by a hands-on approach. Based on their preference you can create a more effective presentation of the needed material. The saying “The more neurons that fire together, wire together” helps us remember that our brains require repetition of information to “hard wire” it, no matter the style.

State the Objectives

There are so many topics that need to be taught regarding diabetes management that it can feel overwhelming to both the clinician and the patient. Before teaching a patient with diabetes, clarify the goal of the learning session. Stating “We’re going to talk about diabetes” isn’t as clear as “You are going to learn how to test your blood sugar daily with this meter” or “You are going to learn how to use an insulin pen to give yourself the medicine your provider ordered.” Notice both sentences focused on what the learner was going to be able to do at the end of the training, rather than what the teacher was going to do.

People need to be able to come away from a teaching or training session with the ability to do something that will make a positive impact on their health, and not to just learn academic concepts. Behavior change is the focus of learning sessions in healthcare. Many times the objective of the learning session is given by the prescribing clinician, it may be learning about insulin devices or counting carbs. If you are the one choosing the topic and don’t know what to teach, ask the patient what they need or want to learn first. Adult learners are generally task-oriented and already know what they want to learn.

Select Appropriate Teaching Methods

Selecting appropriate teaching methods depends on what you have already discovered about your learner’s preferences. The methods of teaching include auditory, visual, one-on-one, group classes, and so on. If a person with diabetes seems interested in a group class, find out your local resources and where you can refer them. If a person says that they prefer private teaching, then schedule that if possible. The following list shows many different methods that could be used for teaching about diabetes:

Audiovisual

Case Study

Computer resources

Conference

Demonstration

E-learning

Group discussion

Gaming

Lecture

One-to-one

Reading

Return demonstration

Role playing

Simulation

Technology

Telecommunications

Workshop

Use Effective Instructional Materials

In addition to selecting appropriate teaching methods, using effective instructional materials is important to creating an effective teaching experience for the patient. If you found, for example, that your learner prefers to learn by watching videos, then a pamphlet may be useless unless it summarizes information from the video. If patients disclose they can’t read well in English, then other teaching methods need to be chosen.

Written instructional methods can be extremely helpful but they must be written at a fifth-grade reading level and without medical jargon. Using pictures can be helpful for those with limited English proficiency. Pharmaceutical representatives often offer diabetes education materials, generally free of cost. The following list identifies some of the many instructional materials available for diabetes:

Anatomical models

Charts

Demonstration materials

Displays

Food models

Graphs

Handouts

Pamphlets

Posters

Puzzles

Videos

Require Learner Performance

Learning for knowledge’s sake alone may not effect the actual behaviors needed to improve physical health. Notice that, within this course, each module identifies a learning objective. Knowledge becomes powerful when it prepares you to improve action toward a desired goal. The four domains of learning depicted earlier include affective (emotional), behavioral (ability to adopt new behaviors), cognitive (knowledge), and psychomotor (physical ability). As a diabetes educator you will choose some combination of these to achieve the goal of improved patient outcomes.

Insurance companies who pay for diabetes education want to know that their teaching impacts physical health for the better. Learning what insulin does isn’t as valuable as developing the skill to inject the insulin correctly and thus improve blood glucose levels. For the patient, learning about hypoglycemia is good but learning to check the blood glucose level regularly and take action when it drops to 60 mg/dL is more relevant for diabetes control.

Choosing an action item for each teaching session is likely to produce a concrete result from the training. Asking the patient “What will you do with this information now?” is meant to connect the learning to an action toward better health. The question is appropriate for you too, what will you do with the knowledge you’re learning in this diabetes course?

Evaluate the Learning

Evaluating the learning experience is important to ascertain whether your explanation was effective. Simply asking “You understand, right?” won’t elicit honest feedback. Many people will say yes just to save face for both their sake and yours. Cultural norms in many Asian cultures demand that patients nod a polite yes even if they don’t understand.

In fact, many people don’t want to admit they didn’t understand. Asking them to state back what you said, or requiring them to do a repeat demonstration after your instruction, will give you a better assessment of their learning. You may see holes in their understanding, which you can then fill. Asking patients to teach you is a good way to assess their understanding. Generally if someone can teach correctly, then they know. Asking open-ended questions after your instruction is also helpful: “Explain to me how insulin works in your body,” or “Tell me how you may know if your blood sugar is getting too low.”

Clinical Scenario

Q: What questions should you ask yourself about using this instructional material?

A: Can the person read? Is the timing right for this patient to learn about diabetes? Does the patient wear glasses? Is there someone else in the family who needs to attend the training session? Is there a language barrier? Is there some other material that this patient will find interesting and informative?