Although dementia has probably been around since humans first appeared on earth, it is only as we live longer that we have begun to see its widespread occurrence in older adults. The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, but there are other types and causes of dementia. In fact, new research is suggesting that “pure” pathologies may be rare and most people likely have a mix of two or more types of dementia.

Worldwide more than 50 million people live with dementia and because people are living longer this number is expected to more than triple by 2050 (ADI, 2018). In Massachusetts, there are 130,000 residents living with Alzheimer’s disease, and by 2025 this number is expected to increase by more than 20,000 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019a).

Defining Dementia

The ugly reality is that dementia often manifests as a relentless and cruel assault on personhood, comfort, and dignity. It siphons away control over thoughts and actions, control that we take for granted every waking second of every day.

Michael J. Passmore, Geriatric Psychiatrist

University of British Columbia

Dementia is a collective name for the progressive, global deterioration of the brain’s executive functions. Dementia occurs primarily in later adulthood and is a major cause of disability in older adults. Although almost everyone with dementia is elderly, dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

Researchers believe that in Alzheimer’s disease toxic changes in the brain destroy the healthy balance that allows neurons (nerve cells) to communicate with each other and other cells (microglia and astrocytes) to clear away debris and keep neurons healthy (NIA, 2017).

The changes involve the protein fragment beta-amyloid and protein tau in which abnormal tau accumulates and eventually forms tangles inside neurons, and beta-amyloid clumps into plaques. These plaques build up slowly between neurons, and when they reach a tipping point tau spreads rapidly through the brain. This buildup triggers microglia, the brain’s immune system cells, but they cannot keep up with the buildup of debris and the result is chronic inflammation. Brain atrophy occurs as cells are lost. As the brain’s ability to metabolize glucose decreases, normal brain function is further affected (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; NIA, 2017)

This process, which may begin years or decades before the first signs of dementia, can be seen in the following video.

How Alzheimer’s Changes the Brain (3:59)

https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/video-how-alzheimers-changes-brain

Current research identifies three stages of Alzheimer’s disease:

- Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (still under investigation) which involves measurable biomarkers but no outward symptoms;

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer’s disease, which also has biomarkers and some symptoms that do not interfere significantly with everyday activities; and

- Dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, which divides into 3 stages: mild, moderate, and severe (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019).

In Alzheimer’s disease, damage begins in the temporal lobe, in and around the hippocampus. The hippocampus is part of the brain’s limbic system and is responsible for the formation of new memories, spatial memories, and navigation, and is also involved with emotions.

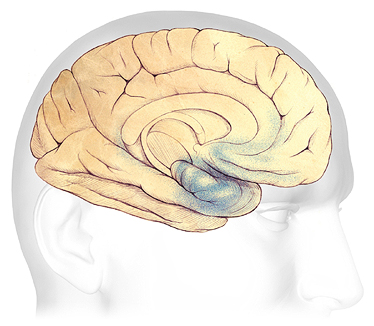

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease (Preclinical)

In the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, before symptoms can be detected, plaques and tangles form in and around the hippocampus (shaded in blue).

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

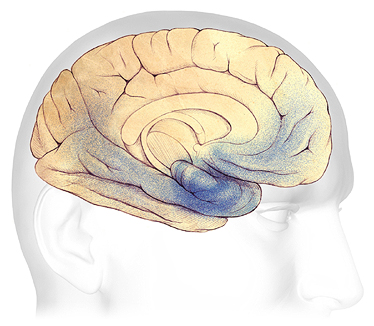

As the disease progresses, plaques and tangles spread to the front part of the brain (the temporal and frontal lobes). These areas of the brain are involved with language, judgment, and learning. Speaking and understanding speech, the sense of where your body is in space, and executive functions such as planning and ethical thinking are affected.

Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease

In mild to moderate stages, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) spread from the hippocampus forward to the frontal lobes.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

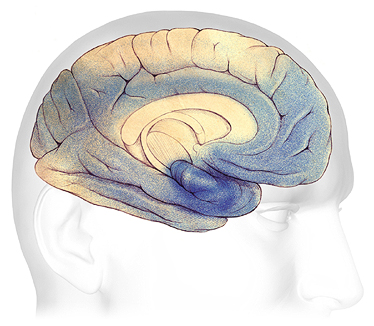

In severe Alzheimer’s disease, damage is spread throughout the brain. Notice in the illustration below the damage (dark blue) in the area of the hippocampus, where new, short-term memories are formed. At this stage, because so many areas of the brain are affected, individuals lose their ability to communicate, to recognize family and loved ones, and to care for themselves.

Severe Alzheimer’s Disease

In advanced Alzheimer’s, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) have spread throughout the cerebral cortex.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

Further research into molecular and cellular mechanisms and their interactions are critical to developing therapies, and progress has been made in identifying underlying factors. Brain imaging advances have allowed observation of the course of plaques and tangles in the living brain, blood and fluid biomarkers can help pinpoint disease beginning and progression, and further understanding of the disease’s genetic underpinnings and their effects are being explored to develop new therapies (NIA, 2017).

Types of Dementia

Although Alzheimer’s disease is the best-known and most common cause of dementia, it is not the only cause, and there are over 100 forms of dementia (ADI, n.d.). Frontal-temporal dementia—which begins in the frontal lobes—is a relatively common type of dementia in those under the age of 60. Vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia are other common types of dementia (see table).

Some Common Types of Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Dementia subtype | Early, characteristic symptoms | Neuropathology | % of dementia cases |

*Alzheimer’s disease (AD) |

|

| 50–75% |

Frontal-temporal dementia |

|

| 5–10% |

*Vascular dementia |

|

| 20–30% |

Dementia with Lewy-bodies |

| Cortical Lewy bodies (alpha-synuclein) | <5% |

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is based on symptoms; no test or technique can diagnose dementia. To guide clinicians, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) has developed the following diagnostic guidelines indicating the presence of Alzheimer’s disease:

- Gradual, progressive decline in cognition that represents a deterioration from a previous higher level;

- Cognitive or behavioral impairment in at least two of the following domains:

- episodic memory,

- executive functioning,

- visuospatial abilities,

- language functions,

- personality and/or behavior;

- Functional impairment that affects the individual’s ability to carry out daily living activities;

- Symptoms that are not accounted for by delirium or another mental disorder, stroke, another type of dementia or other neurological condition, or the effects of a medication. (DeFina et al., 2013)

First promulgated in 1984, the diagnostic guidelines were significantly updated in 2011. While this remains the current iteration, a working group is currently reassessing them for the Alzheimer’s Association (ADI, 2018). The guidelines are available from both the NIA and Alzheimer’s Association websites as well as in numerous open-access journal articles.

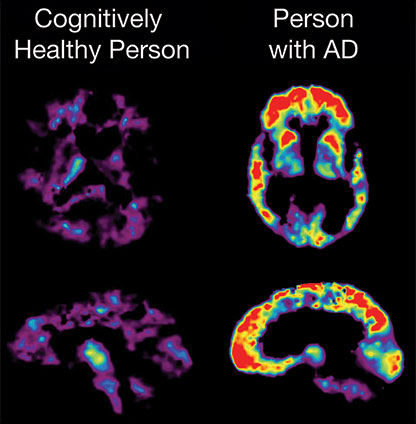

Neuroimaging shows promise in assisting with early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease by detecting visible, abnormal structural and functional changes in the brain (Fraga et al., 2013). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide information about the shape, position, and volume of the brain tissue. It is being used to detect brain shrinkage, which is likely the result of excessive nerve death. Positron emission tomography (PET) is being used to detect the presence of beta amyloid plaques in the brain.

PET Scans Showing PiB Uptake

PET imaging makes it possible to detect beta amyloid plaques using a radiolabeled compound called Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB). In this PET scan, the red and yellow colors indicate that PiB uptake is higher in the brain of the person with AD than in the cognitively healthy person.

Source: NIA, public domain.

Early diagnosis of cognitive impairment is important for a variety of reasons but it is often overlooked. One study indicated that physicians were unaware of cognitive impairment in more than 40% of their patients who were cognitively impaired. While a second study found that more than half of the patients with dementia had never been given a clinical cognitive evaluation by a physician (NIA, 2014).

Practitioners are sometimes concerned about the time needed and the techniques to use when assessing a patient for cognitive impairment. But the good news is that once trained, and using widely available tools, an initial assessment can be done in 10 minutes or less. While such testing can be done at any time, it is now a required part of the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit. In other situations, determining whether or not cognitive testing is needed can be facilitated by use of the Dementia Screening Indicator.

Among the tools available for practitioners to employ in testing for cognitive impairment are the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), the AD8 and the Mini-Cog. Some doctors may also use one of a number of computerized tests that have been cleared by the FDA (NIA, 2014; Alzheimer’s Association, 2019c). If screening is negative, patient and family concerns may be alleviated, at least at that point in time.

If screening is positive and further evaluation is warranted, the patient and physician can work to identify the cause of impairment (for example, medication side effects, metabolic and/or endocrine imbalance, delirium, depression, Alzheimer’s disease). This may result in:

- Treating the underlying disease or health condition

- Managing comorbid conditions more effectively

- Averting or addressing potential safety issues

- Allowing the patient to create or update advance directives and plan long-term care

- Ensuring the patient has a caregiver or someone else to help with medical, legal, and financial concerns

- Ensuring the caregiver receives appropriate information and referrals

- Encouraging participation in clinical research (NIA, 2014; NINDS, 2017).

Screening for cognitive impairment will usually be part of a more comprehensive examination but not all elements may be appropriate for every patient or accomplished by the same practitioner, and what is necessary may be dictated by what is already known about the patient’s situation.

An assessment generally includes:

- Medical history and physical exam. Assessing a person’s medical and family history, current symptoms and medication, and vital signs can help the doctor detect conditions that might cause or occur with dementia. Some conditions may be treatable.

- Neurologic evaluations. Assessing balance, sensory response, reflexes, and other functions helps the doctor identify signs of conditions that may affect the diagnosis or are treatable with drugs. Doctors also might use an electroencephalogram (EEG), a test that records patterns of electrical activity in the brain, to check for abnormal electrical brain activity.

- Brain scans. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect structural abnormalities and rule out other causes of dementia. Positron-emission tomography (PET) can look for patterns of altered brain activity that are common in dementia. Recent advances in PET can detect amyloid plaques and tau tangles in AD.

- Cognitive and neuropsychological tests. These tests are used to assess memory, language skills, math skills, problem-solving, and other abilities related to mental functioning.

- Laboratory tests. Testing a person’s blood and other fluids, as well as checking levels of various chemicals, hormones, and vitamin levels, can identify or rule out conditions that may contribute to dementia.

- Presymptomatic tests. Genetic testing can help some people who have a strong family history of dementia to identify risk for a dementia with a known gene defect.

- Psychiatric evaluation. This evaluation will help determine if depression or another mental health condition is causing or contributing to a person’s symptoms (NINDS, 2017).

- Input from family members as to changes in the person’s thinking skills and behavior may also be relevant (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019).

While some genetic tests are available and may be appropriate when there is a strong family history of dementia, “health professionals do not currently recommend routine genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease” (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019c).

The Future in Research

We were probably terribly naïve to think a brain disorder like Alzheimer’s disease would be more simple than any other human disorder, because there is nobody who thinks that diabetes is simple, or that cardiovascular disease is a simple thing.

Bart de Strooper, Director

UK Dementia Research Institute

In the World Alzheimer’s Report 2018 published by Alzheimer’s Disease International, leading researchers point out that it has become clear that Alzheimer’s is not simple. Just as research has shown that AD is not a normal part of ageing as first thought, it is also not something straightforward with a cure right around the corner. There is still debate, and research is still looking at the relative importance of different proteins, and their relationship to each other, why amyloid develops to such high levels, the role of the APOE e4 gene, and the possible role of numerous lifestyle elements (ADI, 2018).

Research is also important in the field of diagnosis where there have been two major breakthroughs in the last 45 years. The first of these was the establishment of diagnostic guidelines for dementia (discussed above) and the second was in the field of biomarkers—measurable indicators of a biologic condition—where structural scanning (CT, PET, and MRI) finally came to be seen as worth the money they cost. Some researchers are also studying blood and spinal fluid biomarkers, but these are still most important in the research setting than the clinical setting (ADI, 2018).

Even though research for dementia lags behind that for some other diseases and conditions, new work is released all the time and it can be challenging to keep up. As one example, a May 2019 PLOS|ONE research article addressed the issue of diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases causing dementia and the need for methods that can help address the rapid increase in the number of patients presenting for evaluation, the sometimes-prohibitive costs of diagnostic imaging, and the “learning effects which limit the number of possible administrations” of some of the cognitive impairment tests routinely administered in physicians’ offices. This research looked at the promising possibilities for “capturing neurodegeneration-associated characteristics in a person’s voice” noting that “the incorporation of novel methods based on the automatic analysis of speech signals may give us more information about a person’s ability to interact, which could contribute to the diagnostic process” (Al-Hameed et al., 2019).

Conditions That Can Mimic Dementia

A number of medical conditions other than dementia can cause cognitive changes. Gerontology specialists speak of the “3Ds”— delirium, depression, and dementia—because these three conditions are the most common reasons for cognitive changes in older adults. Delirium and depression may be mistaken for dementia.

Delirium

Delirium is a sudden, severe confusion with rapid changes in brain function. Delirium develops over hours or days and is temporary and reversible. Delirium can affect perception, mood, cognition, and attention. The most common causes of delirium in people with dementia are medication side effects, hypo- or hyper-glycemia, fecal impactions, urinary retention, electrolyte disorders and dehydration, infection, stress, and metabolic changes. An unfamiliar environment, injury, or severe pain can also cause delirium.

Delirium is under-diagnosed in almost two-thirds of cases and can be misdiagnosed as depression or dementia. Since the most common causes of delirium are reversible, recognition enhances early intervention. Early diagnosis can lead to rapid improvement (Hope et al., 2014).

Delirium: A Patient Story at Leicester’s Hospital (6:49)

NHS Leicester’s Hospital, England, U.K.

Depression

Depression(major depressive disorder or clinical depression) is a common but serious mood disorder. It causes severe symptoms that can interfere with how a person thinks and feels and with their ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy activities. A diagnosis of depression requires that the symptoms be present for at least two weeks. A person may experience a single episode of depression in their life but multiple episodes are more common (NIMH, 2018, 2016).

Persistent depressive disorder, or dysthymia, is characterized by long-term (2 years or longer) symptoms that may not be severe enough to disable a person but can prevent normal functioning or feeling well. Psychotic depression occurs when a person has severe depression plus some form of psychosis, such as delusions or hallucinations. Psychotic symptoms typically have a depressive “theme,” such as delusions of guilt, poverty, or illness (NIMH, 2018).

Depression is very common in people with Alzheimer’s, and experts believe it may be as high as 40%. It is especially common during the early and middle stages, and treatment can have significant benefits. Diagnosis can be difficult because dementia and depression share many symptoms, including apathy, loss of interest in activities and hobbies, social withdrawal, isolation, trouble concentrating, and impaired thinking. However, it can be difficult for patients with Alzheimer’s to communicate their feelings effectively. Depression in those with Alzheimer’s can be different because it may be less severe, may not last as long and have symptoms that come and go, and a person with Alzheimer’s may not talk about or attempt suicide as often as those with Alzheimer’s (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019b).

Those with co-occurring dementia and depression generally have been found to have a higher mortality rate from all causes. More research is needed, and one question that has been raised is whether there are differences in mortality rates between home-dwelling individuals and those living in nursing homes (Petersen et al., 2017).

Other Conditions

There are other conditions that can cause dementia-like symptoms; many of these conditions can be stopped and may be reversible with appropriate treatment:

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus is an abnormal buildup of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. Elders with the condition usually have trouble with walking and with bladder control before the onset of dementia. Normal pressure hydrocephalus can be treated or even reversed by implanting a shunt system to divert fluid from the brain.

- Nutritional deficiencies of vitamin B1 (thiamine), caused by chronic alcoholism, and of vitamin B12 can be reversed with treatment. People who have abused substances such as alcohol and recreational drugs sometimes display signs of dementia even after the substance abuse has stopped.

- Side effects of medications or drug combinations may cause cognitive impairment that looks like a degenerative or vascular dementia but which could reverse upon stopping these medications.

- Vasculitis, an inflammation of brain blood vessels, can cause dementia after multiple strokes and may be treated with immunosuppressive medications.

- Subdural hematoma, or bleeding between the brain’s surface and its outer covering (the dura), is common after a fall. Subdural hematomas can cause dementia-like symptoms and changes in mental function. With treatment, some symptoms can be reversed.

- Some non-malignant brain tumors can cause symptoms resembling dementia and recovery occurs following their removal by neurosurgery.

- Some chronic infections around the brain, so-called chronic meningitis, can cause dementia and may be treatable by drugs that kill the infectious agent. (NINDS, 2017)