Community agencies, mental health organizations, senior services, veterans support groups, and peer support programs can provide critically needed services, including employment and vocational help, housing assistance, and social interactions that are not focused on illness. Cooperation, collaboration, and communication are critical components of patient referral and recovery.

5.1 Recognition and Referral Training

Recognition and referral training—also called gatekeeper training—helps people without specific psychosocial training identify and refer people who may be at risk of suicide. Specific audiences for gatekeeper training include high school teachers and students, first responders, faith community leaders, people who work with older adults, LGBT youth, men in the middle years, and those involved in the criminal justice system (SPRC, 2018).

Gatekeeper trainings vary widely in their length, and depth of content, and target audience. They also vary by modality, with some utilizing online platforms and others offering in-person trainings (Spafford, 2023). Gatekeeper training is only one part of a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention.

It is of limited value if safety protocols are lacking as well as ways to help people find local agencies, professionals, and mental health professionals who can de-escalate suicidal crises (SPRC, 2018).

Gatekeeper trainings is most effective when the training is adapted to meet the specific cultural needs of the community in which they are used. Culturally speaking, who are the people being trained? Some populations share multiple cultures, so it is important to be as specific as possible. Possible groups can include (but are not limited to) race, ethnicity, spirituality, deaf and hard of hearing, LGBTQ2S, gender identity, tribal identity, military/veteran, socioeconomic status, and educational level (SPRC, 2020).

For providers who already have mental health training, recognition and referral training can still be a valuable training tool. It provides additional education, support, access to resources, and opportunities to practice assessment skills. Despite the comorbidity of mental health disorders and suicide, most mental health professionals—a group that includes psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, licensed counselors, and psychiatric nurses—do not typically receive routine training in suicide assessment, treatment, or risk management.

5.2 Crisis Lines

Crisis lines provide immediate access, often 24 hours a day, for crisis intervention. They are an access point for emergency care, clinical assessment, referral, and treatment. When other providers are closed and personal support networks are unavailable, crisis lines can be a lifeline for people at risk of suicide.

5.2.1 988 Crisis Line

Crisis intervention programs provide support and referral services, typically by directing a person in crisis (or a friend or family member of someone at risk) to trained volunteers or professional staff via telephone hotline, online chat, text messaging, or in person. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is now known as the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. It is active across the United States.

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is made up of an expansive network of over 200 local and state funded crisis centers located across the United States. The counselors at these local crisis centers answer calls and chats from people in distress every day. The Lifeline’s crisis centers provide the specialized care of a local community with the support of a national network.

Source: SAMHSA, 2022.

In an evaluation of the effectiveness of the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline to prevent suicide, more than 1,000 suicidal individuals who called the hotline completed a standard risk assessment for suicide. Researchers found that over half of the initial sample had a plan for their suicide when they called. Significant decreases in psychological pain, hopelessness, and intent to die occurred during the phone call, with sustained decreases in psychological pain and hopelessness up to three weeks later. These results are promising and underscore the importance of continued care following the call (CDC, 2022).

A 2022 Harris poll assessed public perception of suicide prevention services, including crisis lines. More than half of the 2,054 respondents said they had at least heard of the National Suicide Prevention Hotline although many were not familiar with its recent 988 designation.

Respondents to the Harris poll reported at least one barrier to reaching out to crisis services (SPRC, 2022 September):

- Fear of out-of-pocket costs (26%)

- Fear of what my family would think (26%)

- Lack of confidence that services in my area can help (25%)

- Fear of police/law enforcement responding (24%)

- Lack of insurance to cover costs (24%)

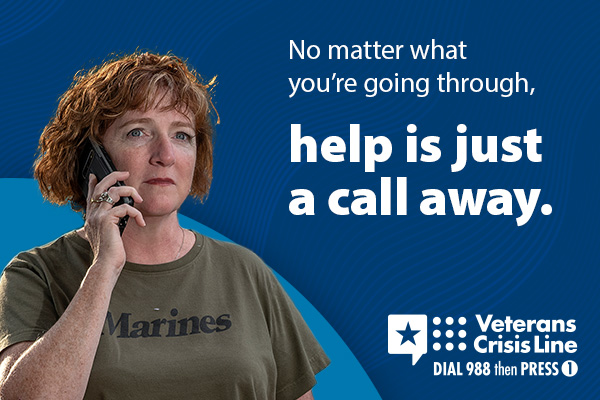

Veterans Crisis Line

Source: Department of Veterans Affairs, 2024.

The Military Crisis Line is a free, confidential resource for all service members, including members of the National Guard and Reserve, and Veterans, even if they’re not enrolled in VA benefits or healthcare. It is available 24/7 and is free and confidential. Phone, chat, and text services are available for service members stationed outside the United States (DVA, 2024).

5.3 Online Tools and Mobile Applications

Technology has created new possibilities for suicide prevention and referral. For some mental health problems, such as depression, online tools and mobile applications provide resources for self-help, which can detect symptoms of distress, and offer contact to hotlines or referral to other resources (Pauwels et al., 2017).

Online and mobile tools supplement traditional medical treatments and can be helpful for those who are reluctant or unable to find professional treatment. These tools provide an additional source of support and can lower the barrier to seeking professional help. Online tools and programs for suicide prevention create new possibilities due to their discretion, accessibility, availability, and low cost, which are important barriers for help seeking (Pauwels et al., 2017).

5.4 Continuity of Care

Caring for suicidal persons will most likely require multiple levels of services in a team environment. Discharge from one level of care must incorporate linkages to other necessary levels of care. Organizations must recognize, accept, and implement shared service responsibilities both among various clinical staff within the organization and among providers in the larger community.

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention

Continuity of care means there is coordination between different patient services and providers. This includes the smooth and effective transmission of information for the patient’s treatment and management. Poor or lacking continuity of care is related to elevated risk of hospital readmission and attempted and completed suicide, while better continuity of care appears to be protective against suicidality (Arnon et al., 2024).

Key components of good continuity of care within a healthcare organization includes (Arnon et al., 2024):

- Designating a suicide coordinator.

- Monitoring admissions related to suicide attempts.

- Training staff.

- Establishing written protocols.

- Implementing an agreed upon plan.

- Structuring collaboration between providers.

Because a variety of healthcare providers, friends, and family members may be associated with the care of a person at risk for suicide, continuity of care can be easily lost. Maintaining continuity across facilities and providers can be helped by electronic medical records; however, not everyone has access to this information. A confounding factor is that mental health information has higher levels of consent for accessing records.

It is estimated that about 23% of suicides are partially attributed to continuity of care issues. This can include admission difficulties, patient refusal of services, limited services offered by a continuing care team, abrupt termination of services, lack of community follow-up, poor transition between services, and the loss of or change in case manager (Arnon et al., 2024).

Continuity of care is often interrupted when patients transition between care facilities or between other health systems or provider organizations. Patients have expressed frustration with seeing multiple providers, both within a treatment facility and across multiple locations (DVA/DOD, 2019).

Continuity of care is improved when providers directly contact other providers and schedule follow-up appointments. Transition support services (such as telephone or telehealth contact with behavioral health providers) can improve continuity of care and prevent delays in follow-up services (DVA/DOD, 2019).

Additional practices that improve continuity of care include telephone reminders of appointments, providing a “crisis card” with emergency phone numbers and safety measures, or sending a letter of support. Motivational counseling and case management can also be used to promote adherence to the recommended treatment (HHS, 2012, latest available).

Unfortunately, many patients with high suicide risk are never referred for follow-up care and receive only limited mental health services. Many also fail to receive adequate treatment for underlying mental health or substance use disorders.