UNAIDS reports that reaching Fast-Track Targets will avert nearly 28 million new HIV infections and end the AIDS epidemic as a global health threat by 2030.

If the world does not rapidly scale up in the next five years, the epidemic is likely to spring back with a higher rate of new HIV infections than today.

UNAIDS, 2014a

Your client, Mr. Glover, has been diagnosed with HIV. You don’t know much about HIV and are concerned whether you can “catch” HIV by working with him or even shaking hands. You recognize your need to be better educated so you can give appropriate care without bias or fear. You know that quality care can be given when you have a sound understanding of the disease, risk factors, diagnostics, clinical symptoms, and treatments. Becoming culturally sensitive to the unique needs of your patients requires you to better understand your patient’s values, definitions of health and illness, and preferences for care.

Definitions of HIV and AIDS

[Note: If not otherwise identified, material in this course is taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.]

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has infected tens of millions of people around the globe in the past three decades, with devastating results. In its advanced stage—acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)—the infected individual has no protection from diseases that may not even threaten people who have healthy immune systems. While medical treatment can delay the onset of AIDS, no cure is available for HIV or AIDS.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) kills or impairs the cells of the immune system and progressively destroys the body’s ability to protect itself. Over time, a person with a deficient immune system (immunodeficiency) may become vulnerable to common and even simple infections by disease-causing organisms such as bacteria or viruses. These infections can become life-threatening.

The term AIDS comes from “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.” AIDS refers to the most advanced stage of HIV infection. Medical treatment can delay the onset of AIDS, but HIV infection eventually results in a syndrome of symptoms, diseases, and infections. The diagnosis of AIDS requires evidence of HIV infection and the appearance of specific conditions or diseases beyond just the HIV infection. Only a licensed medical provider can make an AIDS diagnosis. A key concept is that all people diagnosed with AIDS have HIV, but an individual may be infected with HIV and not yet have AIDS.

HIV-Infection in the Body

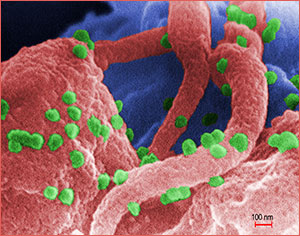

Human Lymphocyte Showing HIV Infection

A scanning electron micrograph showing HIV-1 virions (in green) on the surface of a human lymphocyte. HIV was identified in 1983 as the pathogen responsible for AIDS. In the infected individual, the virus causes a depletion of T-cells, which leaves these patients susceptible to opportunistic infections and to certain malignancies. Source: Public Health Image Library, image #11279, CDC, 1989.

HIV enters the bloodstream and attacks T-helper lymphocytes, which are white blood cells essential to the functioning of the immune system. One of the functions of T-helper cells is to regulate the immune response in the event of attack from disease-causing organisms such as bacteria or viruses. The T-helper lymphocyte cell is also called the T4 or the CD4 cell. When any pathogen infects the T-helper lymphocyte, the T cell sends signals to other cells, which produce helpful antibodies.

Antibodies (proteins made by the immune system in response to infection) are produced by the immune system to help get rid of specific foreign invaders that can cause disease. Producing antibodies is an essential function of our immune system. The body makes a specific antibody for each pathogen. For example, if we are exposed to the measles virus, the immune system will develop antibodies specifically designed to attack that virus. Polio antibodies fight the polio virus. A healthy immune system creates customized identification of pathogens, which results in the body’s ability to target and kill invading microorganisms. When our immune system is working correctly, it protects against these foreign invaders.

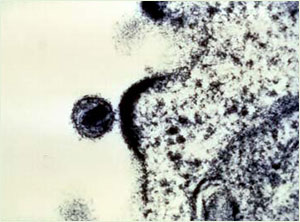

HIV “Budding” Out of a T-cell

Source: NIAID, courtesy of Dr. Tom Folks.

HIV infects and destroys the T-helper lymphocytes and damages their ability to signal for antibody production. This results in the eventual decline of the immune system. The HIV is then able to reproduce without being killed from the body. CD4 counts therefore are of great importance to people with HIV to confirm their ability to fight infection. The normal range for CD4 is between 500 and 1,500. A CD4 count below 200 reveals the body’s inability to create antibodies and fight infection, putting the client at greater risk for AIDS and other potentially fatal opportunistic infections. Serum lab results may also express CD4 percentage, and a normal result in an HIV negative person is between 25% and 65%, identifying that percentage of lymphocytes are CD4 cells. The remaining cells are other types of lymphocytes also involved in the immune attack against pathogens.

Primary HIV Infection

Primary HIV infection (acute HIV infection) is the first stage of HIV disease. It begins with initial infection and typically lasts only a week or two. During this time the virus is establishing itself in the body but the body has not yet begun to produce antibodies. Because of this, the infection cannot be identified by any HIV tests.

This period of acute infection is characterized by a high viral load (large numbers of the virus) and a decline in CD4 cells. Approximately half of infected patients experience clinical symptoms mimicking mononucleosis that include fever and swollen glands during the primary infection, but the symptoms are not life-threatening and may be misinterpreted as a minor illness.

During a primary infection, newly infected people can infect partners because they do not yet know they have HIV. The primary infection period ends when the body begins to produce HIV-specific antibodies as the CD4 cells are still able to respond. The number of antibodies is still insufficient, however, to be detectable by HIV testing.

Test Your Learning

Primary HIV infection is:

- The period beginning when AIDS is diagnosed.

- The time when antibodies are first detected.

- Referred to as the window period.

- The first weeks after infection when the body has not yet produced antibodies.

Online Resource

Answer: d

Video: How HIV Kills So Many CD4 T Cells

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8gnpnUFNloo

Window Period

The window period is the period of time between initial infection with HIV and the point when the body produces detectable antibodies, which can vary from 2 to 12 weeks. During the window period a person is infectious, with a high viral load, but still presents with a negative HIV antibody test. This false negative test means the infected person might get a negative test result while actually having HIV. The point when the HIV antibody test becomes positive is called seroconversion.

Test Your Learning

The window period:

- Is the time between infection with HIV and the body’s production of detectable antibodies.

- Typically lasts only a week or two.

- Refers to the stage of disease when the newly infected person is not yet contagious.

- Is the first stage of HIV disease.

Answer: a

Asymptomatic Stage

After the acute stage of HIV infection, people infected with HIV continue to look and feel completely well for long periods, sometimes for many years. During this time, the virus is replicating and slowly destroying the immune system. This asymptomatic stage is sometimes referred to as clinical latency. This means that, although a person looks and feels healthy, they can infect other people through any body fluid contact such as unprotected anal, vaginal, or oral sex or through needle sharing.

The virus can also be passed from an infected woman to her baby during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding when she is unaware of being HIV positive. Unless the infected person is given antiretroviral therapy, the onset of AIDS can occur an average of 10 years after being infected with HIV.

Apply Your Learning

Q: If a person has been infected with HIV but is not symptomatic, how would you explain this to a patient with HIV?

A: Although there may be no clinical symptoms, the HIV is replicating and slowly attacking the immune system’s CD4 cells. An untreated person can look and feel healthy, sometimes for many years, however the virus is still present in the blood and can cause infection in others. Also, the virus can be passed through unprotected sex and from pregnant or lactating mother to child.

The Origin of HIV

Since the human immunodeficiency virus was identified in 1983, researchers have worked to pinpoint the origin of the virus. In 1999 an international team of researchers reported that they discovered the origins of HIV-1, the predominant strain of HIV in the developed world. A subspecies of chimpanzees native to West Equatorial Africa was identified as the original source of the virus. Researchers believe that HIV-1 was introduced into the human population when hunters became exposed to infected blood. The transmission of HIV was driven through Africa by migration, housing, travel, sexual practices, drug use, war, and economics that affect both Africa and to the entire world.

HIV Strains and Subtypes

HIV is divided into two primary strains: HIV-1 and HIV-2. Worldwide, the predominant virus is HIV-1, and generally when people refer to HIV without specifying the type of virus they are referring to HIV-1. The relatively uncommon HIV-2 type is concentrated in West Africa and is rarely found elsewhere.

HIV is a highly variable virus that easily mutates. This means there are many different strains of HIV, even within the body of a single infected person. Based on genetic similarities, the numerous viral strains may be classified into types, groups, and subtypes.

Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 have several subtypes. It is certain that more undiscovered subtypes already exist. It is also probable that more HIV subtypes will evolve in the future. As of 2001, blood testing in the United States can detect both strains and all currently known subtypes of HIV.

Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS

Epidemiology is the study of how disease is distributed in populations and the factors that influence the distribution. Epidemiologists try to discover why a disease develops in some people and not in others. Clinically, AIDS was first recognized in the United States in 1981. In 1983 HIV was discovered to be the cause of AIDS. Since then, the number of AIDS cases has continued to increase both in the United States and in other countries.

HIV and AIDS cases are reportable; each state has its own laws and healthcare workers must be familiar with those of the state in which they are licensed.

The discovery of combination antiviral drug therapies in 1996 resulted in a dramatic decrease in the number of deaths due to AIDS among people given the drug therapies. On the down side, many people who have access to the therapies may not benefit from them or may not be able to tolerate the side effects. The medications are expensive and require strict dosing schedules. Furthermore, in developing countries many people with HIV have no access to the newer drug therapies.

People who are infected with HIV come from all races, countries, sexual orientations, genders, and income levels. Globally, most of the people who are infected with HIV have not been tested, and are unaware that they are living with the virus. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that 1.2 million people aged 13 years and older are living with HIV infection, including 168,000 (14%) who are unaware of their infection. This is a decline from 25% in 2003 and 20% in 2012, and it is a positive sign because studies have shown that people with HIV who know that they are infected avoid behaviors that spread infection to others; also, they can get medical care and take antiviral medications that could eventually reduce HIV spread by as much as 96% (CDC, 2016a).

CDC estimates that that there are only 4 transmissions per year for every 100 people living with HIV in the United States, which means that at least 95% of people living with HIV do not transmit the virus to anyone else. This represents an 89% decline in the transmission rate since the mid-1980s, reflecting the combined impact of testing, prevention counseling, and treatment efforts targeted to those living with HIV infection (CDC, 2013).

The estimated incidence of HIV has remained generally stable in recent years, at about 50,000 new HIV infections per year (CDC, 2014a). While this number is still too high, stabilization is in itself a sign of positive progress. With continued increases in the number of people living with HIV due to effective HIV medications, there are potentially more opportunities for HIV transmission than ever before. Yet, the annual number of new infections has not increased (CDC, 2013).

Worldwide, there were about 2.1 million new cases of HIV in 2013, and about 35 million people are living with HIV around the world. Of those, 3.2 million are children, 2.1 million are adolescents, and 4.2 million are people over age 50. In 2013 new HIV infections worldwide were 2.1 million, but new infections have fallen 38% since 2001 and new infections among children have fallen by 58% in the same period (CDC, 2014b; UNAIDS, 2014b).

Through 2011 the cumulative estimated number of deaths of people with diagnosed HIV infection ever classified as stage 3 (AIDS) in the United States was 648,000 (deaths may be due to any cause, which can make data interpretation complex). Nearly 39 million people with AIDS have died worldwide since the epidemic began (CDC, 2014b).

Globally, AIDS-related deaths, which peaked in 2005 at 2.4 million and have declined steadily ever since, were estimated at 1.5 million in 2013 (UNAIDS, 2014a). Even though Sub-Saharan Africa bears the biggest burden of HIV/AIDS, countries in South and Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and those in Latin America are significantly affected by HIV and AIDS (CDC, 2014b; UNAIDS, 2014b).

In 2014 UNAIDS set forth the goal known as 90-90-90, which means that, by 2020,

- 90% of people living with HIV will know their HIV status.

- 90% of those diagnosed with HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy.

- 90% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression. (UNAIDS, 2018)