The Veterans Health Administration, or VA, is the nation’s largest integrated single payer healthcare system, with nearly 1,400 healthcare facilities, including 170 medical centers and close to 1,200 outpatient clinics. It serves more than 9 million veterans each year (VA, 2024). Services include inpatient hospital care such as surgery, home-based rehabilitation, prescriptions, vaccinations, and mental healthcare. Healthcare for specific groups like geriatric patients and their caregivers, homeless veterans and rural veterans is also available.

There are a number of challenges associated with providing comprehensive healthcare to such a large population. Veterans are often clinically complex, with many suffering from chronic health problems like PTSD, traumatic brain injury and other service-related injuries. There is also a high prevalence of comorbid conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and hypertension. Many rural and low-income veterans receive most of their healthcare from VA (Rasmussen and Farmer, 2023). In recent years, the VA has expanded its offerings to include additional services such as optometry and ophthalmology (AOA, 2023).

In the wake of public attention to long wait times at VA clinics, Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act in 2014. Known simply as the Veterans Choice Program, this benefit allows eligible veterans to receive healthcare in their communities rather than waiting for a VA appointment or traveling to a VA facility. The American Medical Association (AMA) strongly supported the passage of Veterans Choice in 2014. Veterans are eligible for the program if they are unable to receive timely care—defined as wait times of more than 30 days; or if they live too far away from a VA facility, defined as more than 40 miles.

Veterans Choice led to an expansion of the Community Care program, which allows the VA to contract its patients’ healthcare with other providers. This requires skillful coordination between healthcare systems, which are often sparse in rural and underserved areas.

2.1 Patient-Centered Community Care

Patient-Centered Community Care (PC3) is a VA program to provide veterans with access to some types of medical care when the local VA medical facility cannot readily provide that care. Eligible veterans can receive access to primary care, inpatient specialty care, outpatient specialty care, mental health care, limited emergency care, and limited newborn care for enrolled female veterans following the birth of a child.

2.1.2 TRICARE

The TRICARE program supports healthcare providers’ work with active-duty and retired service members by reimbursing them for medical and behavioral health services provided outside of a military treatment facility. TRICARE is part of the Military Health System, under the auspices of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. It covers an ever-growing 9.5 million beneficiaries, including active-duty members and families of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Coast Guard, as well as retirees from each of the above services and their families (Health.mil, 2024).

2.1.3 Mobile Vet Centers

In rural communities, gaining access to veterans’ healthcare services, including Vet Centers, can be difficult. Community-based Vet Centers provide social and psychological services, including professional counseling, to eligible veterans. Common challenges for veterans are transitioning from military to civilian life, overcoming trauma, and figuring out how to navigate the VA.

Counseling sessions are one of the most important resources available at the Mobile Vet Centers that are equipped with video-conferencing equipment as well as WIFI and DVD hardware. Source: va.gov.

Veterans who live in communities that do not have Vet Centers may be able to utilize those same services at a Mobile Vet Center. These 83 vehicles have space for confidential counseling, and they can gain access to records through an encrypted connection (DVA, 2024, February 21). Veterans can use them to receive services such as counseling for posttraumatic stress disorder and military sexual trauma, bereavement counseling, marriage and family counseling, and resources such as VA benefits information and suicide prevention referrals.

Jesse Davis made use of mobile vet services in a different way. He came to the vet center in Morgantown, WV, for employment assistance and was promptly hired as the driver for their mobile vet center. His experience as a truck driver in the Marine Corps helped him qualify to drive the mobile vet vehicle. Since his employment, Davis has traveled to West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC, to provide information and referral services to veterans.

He greatly enjoys helping Veterans, especially because he can relate to the challenges of transitioning into civilian life. “The more Veterans I’m around, the more my confidence goes up. And the more my confidence goes up, the more I can help others with information. That’s important for me and I love my job because of it.”

Source: Megan Tyson, VA staff writer.

2.2 Stigma as Barrier to Veterans Getting Services

Stigma, including self-stigmatization has an estimated prevalence of over 40% among adults suffering from PTSD. Even the name of the disorder can discourage people from seeking treatment, as indicated by a survey of over a thousand subjects, two-thirds of whom agreed that changing the name to post traumatic stress injury would reduce the stigma associated with having a disorder and increase the likelihood that patients would seek medical help (Lipov, 2023).

Stigma prevents many people, especially military personnel, from seeking mental healthcare. This includes public stigma as well as self-stigma, where fear and disdain for people with mental illness are internalized. Stigma can be a particularly oppressive barrier in military culture, where mental or emotional disorders are viewed as a personal weakness. Public stigma can have real consequences, as active-duty military personnel in a recent study reported concerns that their careers could be negatively affected if they seek treatment.

Self-stigma is more nuanced, lowering self-esteem and the motivation to seek help. People are also less likely to seek help if they think their disorder is their own fault. This leads to efforts to hide or suppress signs of mental illness, rather than attempting to resolve the issue (McGuffin et al., 2021). While emotional distress often resolves over time, a persistent mental health disorder can deteriorate if left untreated.

One of the VA’s top clinical priorities is preventing veterans from committing suicide. The VA provides, pays for or reimburses the cost of suicide care and treatment at a VA or non-VA facility. This includes ambulance transportation, prescriptions, up to 30 days of inpatient or crisis residential treatment, and up to 90 days of outpatient care at no cost to veterans (Cox, 2023).

This means veterans can get mental healthcare treatment through the Community Care program, as well as directly through the VA. Veterans can also use a crisis hotline by calling 988, texting 838255, or chatting online with the Veterans Crisis line to get connected to a trained mental healthcare professional. The VA is also researching stigma and is offering counseling on how people can change their own perceptions of themselves and others. The Veteran Integrated Service Network 5 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Centers offers a nine-session program on reducing stigma so veterans can get on with their recovery, and their lives (Love, 2024).

2.3 For Healthcare Providers in West Virginia

West Virginia is an example of a largely rural state with a large veteran population and high rates of poverty. According to a 2024 report, West Virginia scored of 49 (out of 50 states and the District of Columbia), on an analysis of state healthcare systems. Only Alabama and Mississippi fared worse. West Virginia is 44 in terms of affordability, and 48 in terms of health outcomes (McCann, 2024).

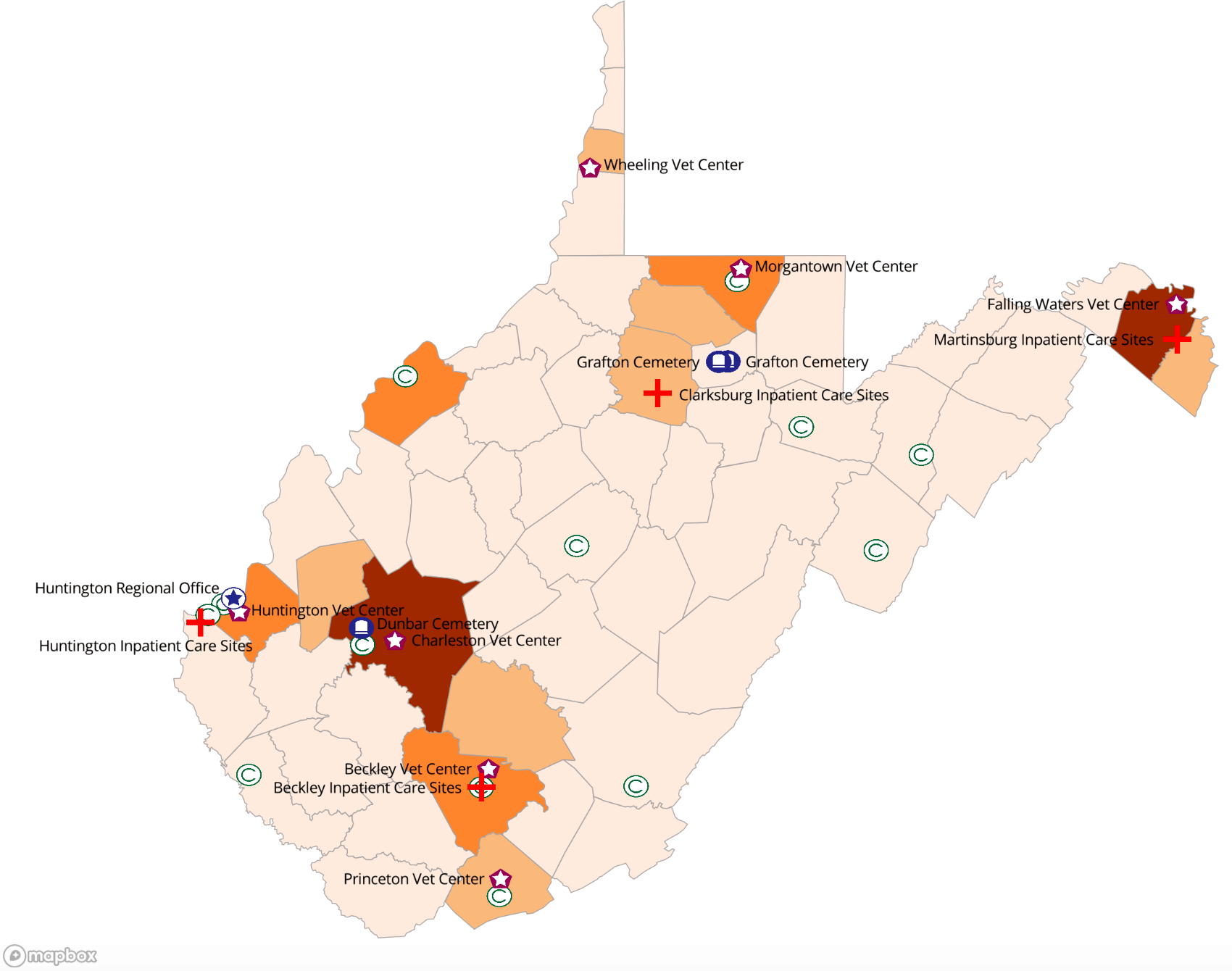

Among its civilian hospitals, West Virginia has 25 university-owned hospitals and 6 owned by the State Department of Health Facilities. As of 2023, West Virginia is home to more than 125,000 veterans (38th in total veteran population). IN West Virginia, there are 17 VA outpatient clinics and 4 VA hospitals, most of them clustered near the borders with Virginia and Pennsylvania, where the highest concentration of veterans live. Many counties in West Virginia do not have a VA clinic, making telehealth the best option for many veterans in those areas (US Census Bureau, 2023, October 19).

Map Showing Distribution of Veterans by County and Location of Care Sites

Graphic courtesy of Department of Veterans Affairs, Distribution of Veterans by County (FY2023), West Virginia https://www.data.va.gov/stories/s/NCVAS-State-Summary-West-Virginia-FY2023/cgsj-chh2/