Although dementia has probably been around since humans first appeared on earth, it is only as we live longer that we have begun to see its widespread occurrence in older adults. The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, but there are other types and causes of dementia. In fact, new research is suggesting that “pure” pathologies may be rare and most people likely have a mix of more than one type of dementia.

Worldwide more than 50 million people live with dementia and because people are living longer this number is expected to triple by 2050 (ADI, 2019). In Florida, there are 510,000 residents currently living with Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019) and by 2025, this number is expected to increase by more than 200,000.

In Florida, about 43% of residents in certified nursing homes have dementia and an additional 30% have some other psychological diagnosis (Harrington & Carrillo, 2018). This means understanding the issues and complexities associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is critical for family, friends, and anyone working in a nursing home, adult day care facility, or hospice, no matter what their education or background.

Defining Dementia

The ugly reality is that dementia often manifests as a relentless and cruel assault on personhood, comfort, and dignity. It siphons away control over thoughts and actions, control that we take for granted every waking second of every day.

Michael J. Passmore, Geriatric Psychiatrist

University of British Columbia

Dementia is a collective name for the progressive, global deterioration of the brain’s executive functions. Dementia occurs primarily in later adulthood and is a major cause of disability in older adults. Although almost everyone with dementia is elderly dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

The exact cause of dementia is still unknown. In Alzheimer’s disease, and likely in other forms of dementia, damage within the brain is thought to be due to the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, and degeneration neurons in the cerebrum. These processes are clearly explained in the following video.

Inside the Brain: Unraveling the Mystery of Alzheimer’s Disease [4:22]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NjgBnx1jVIU

In Alzheimer’s disease, damage begins in the temporal lobe, in and around the hippocampus. The hippocampus is part of the brain’s limbic system and is responsible for the formation of new memories, spatial memories and navigation, and is also involved with emotions.

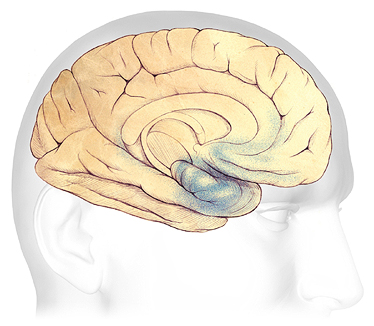

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease

In the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, before symptoms can be detected, plaques and tangles form in and around the hippocampus (shaded in blue).

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

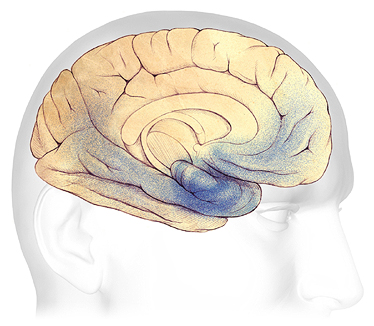

As the disease progresses, plaques and tangles spread to the front part of the brain (the temporal and frontal lobes). These areas of the brain are involved with language, judgment, and learning. Speaking and understanding speech, the sense of where your body is in space, and executive functions such as planning and ethical thinking are affected.

Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease

In mild to moderate stages, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) spread from the hippocampus forward to the frontal lobes.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

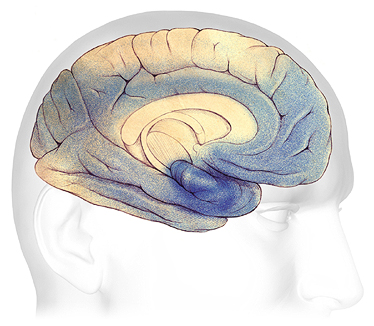

In severe Alzheimer’s disease, damage is spread throughout the brain. Notice in the illustration below the damage (dark blue) in the area of the hippocampus, where new, short-term memories are formed. At this stage, because so many areas of the brain are affected, individuals lose their ability to communicate, to recognize family and loved ones, and to care for themselves.

Source: Adapted with permission from Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2019.

Severe Alzheimer’s Disease

In advanced Alzheimer’s, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) have spread throughout the cerebral cortex.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

It is now thought that the brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease begin years, or even decades, before symptoms emerge. The changes eventually reach a threshold at which the onset of a gradual and progressive decline in cognition becomes obvious (DeFina et al., 2013).

Types of Dementia

Although Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, it isn’t the only cause. Frontal-temporal dementia—which begins in the frontal lobes—is a relatively common type of dementia in those under the age of 60. Vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia are other common types of dementia (see table). In all, more than twenty different types of dementia have been identified.

Some Common Types of Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Dementia subtype |

Characteristic symptoms |

Neuropathology |

% of cases |

*Alzheimer’s disease (AD) |

|

|

60%–80% |

Frontal-temporal dementia |

|

|

5%–10%, prevalence thought to be underestimated |

*Vascular dementia |

|

|

20%–30% |

Dementia with Lewy bodies (closely related to Parkinson’s disease dementia) |

|

|

~5%-10% |

Diagnostic Guidelines

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is based on symptoms; no test or technique that can diagnose dementia. To guide clinicians, in 2011 the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) published updated diagnostic guidelines, which are intended to provide a deeper understanding Alzheimer’s disease than earlier guidelines. The 2011 guidelines:

- Recognize that Alzheimer’s disease progresses on a spectrum with three stages: (1) an early, preclinical stage with no symptoms; (2) a middle stage of mild cognitive impairment; and (3) a final stage marked by symptoms of dementia. Cognitive decline is gradual and progressive.

- Expand the criteria for Alzheimer’s dementia beyond memory loss as the first or only major symptom and recognize that other aspects of cognition, such as word-finding ability or judgment, may become impaired first. Other cognitive changes can include changes in:

- Episodic memory

- Executive functioning

- Visuospatial abilities

- Language functions

- Personality and/or behavior

Since the publication of the 2011 guidelines, researchers have increasingly come to understand that cognitive decline in AD occurs continuously over a long period, and that progression of biomarker measures* is also a continuous process that begins before symptoms are evident. The disease is now regarded as a continuum rather than three distinct clinically defined stages (Jack et al., 2018).

*β amyloid deposition, pathologic tau, and neurodegeneration/neuronal injury.

A 2018 update of the 2011 NIA-AA diagnostic guidelines added a “numerical clinical staging scheme.” This staging scheme reflects the sequential evolution of AD from an initial stage characterized by the appearance of abnormal biomarkers in asymptomatic individuals. As biomarker abnormalities progress, the earliest subtle symptoms become detectable. Further progression of biomarker abnormalities is accompanied by progressive worsening of cognitive symptoms, culminating in dementia (Jack et al., 2018).

The numerical clinical staging scheme is as follows:

- Performance within expected range on objective cognitive tests.

- Normal performance within expected range on objective cognitive tests. (Transitional cognitive decline: Decline in previous level of cognitive function, which may involve any cognitive domains.

- Performance in the impaired/abnormal range on objective cognitive tests.

- Mild dementia.

- Moderate dementia.

- Severe dementia. (Jack et al., 2018)

In 2018 an Alzheimer’s Association workgroup lead by Alireza Atri published a report describing the need for clinical practice guidelines for use in primary and specialty care settings. The guidelines build on the NIA_AA guidelines but add a clinical component for the evaluation of cognitive impairment thought to be related to Alzheimer’s disease or a related type of dementia.

Key components include:

- All middle-aged or older individuals who self-report or whose care partner or clinician report cognitive, behavioral or functional changes should undergo a timely evaluation.

- Concerns should not be dismissed as “normal aging” without a proper assessment.

- Evaluation should involve not only the patient and clinician but, almost always, also involve a care partner (e.g., family member or confidant). (Atri, 2018)

Neuroimaging and CSF Biomarkers

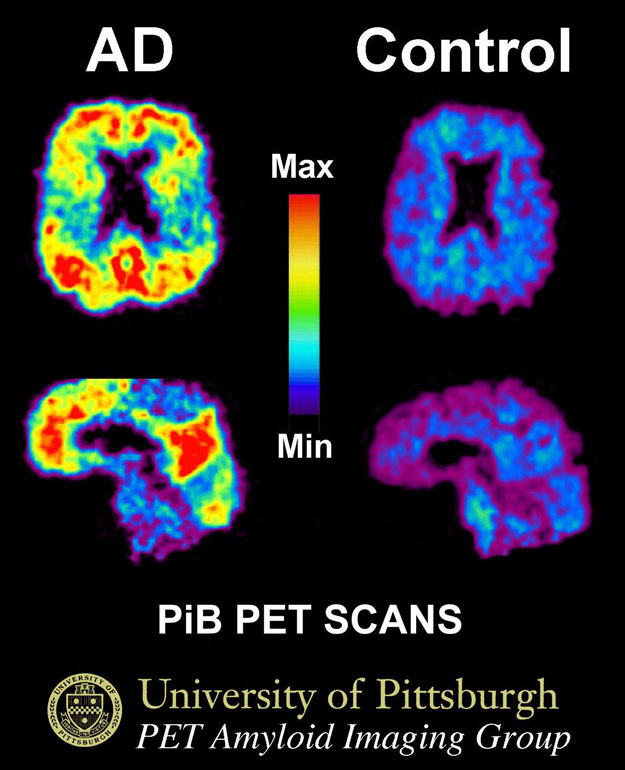

PET Scans Showing PiB Uptake

This image shows a PiB-PET scan of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease on the left and an elderly person with normal memory on the right. Areas of red and yellow show high concentrations of PiB in the brain and suggest high amounts of amyloid deposits in these areas. Source: By Klunkwe—Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Neuroimaging is increasingly being used to assist with early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias by detecting visible, abnormal structural and functional changes in the brain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide information about the shape, position, and volume of the brain tissue and is being used to detect brain shrinkage, which is related to excessive nerve death. Positron emission tomography (PET) uses a radioactive dye called PiB to detect the presence of beta amyloid plaques in the brain.

CSF biomarkers are measures of the concentrations of proteins in cerebral spinal fluid from the lumbar sac that reflect the rates of both production (protein expression or release/secretion from neurons or other brain cells) and clearance (degradation or removal) at a given point in time.

Sensory Impairment and the Changing Brain

Sensory impairment is something often overlooked by caregivers and healthcare professionals when interacting with an older adult with dementia. Both hearing impairment and visual impairments must be taken into account when assessing difficult behaviors as well as a person’s ability to complete common activities of daily living.

For a person with dementia, hearing and visual impairments are associated with adverse outcomes. For example, hearing impairment is associated with poor self-rated health, difficulties with basic and instrumental activities of daily living, difficulty with memory, frailty, and falls (Guthrie et al., 2018).

Similarly, visual impairment has been linked to an increased risk of mortality, difficulties with independence in activities of daily living, difficulty with mobility, and reduced social participation. Individuals with visual impairment also are more likely than those without visual impairment to require community-based supports (Guthrie et al., 2018).

Loss of cells in the part of the brain that processes vision (occipital lobe) causes a narrowing of the visual field and a loss of peripheral vision. Vision becomes narrows and becomes binocular, which means items placed on a table in front of a person (such as food) may be outside of a person’s remaining visual field. Vision is also a critical for good balance and visual impairment means a person begins to rely on touch to help with balance.

Macular degeneration, a common visual impairment in older adults causes loss of vision in the center of the eye, making it difficult to see something directly in front of you.

Because of damage to the visual pathways in the brain, the visual field narrows, making it difficult to see above, beside, and below. Source: National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health. Public domain.

Normal vision on the left and damage cause by macular degeneration on the right. Source: National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health. Public domain.

Conditions That Can Mimic Dementia

There are medical conditions other than dementia can cause cognitive changes in older adults. Gerontology specialists speak of the “3Ds”—dementia, delirium, and depression—because these three conditions are the most common reasons for cognitive changes in older adults. Delirium and depression are often mistaken for dementia. As a care provider with direct, daily contact with clients, your observations and feedback help healthcare providers identify changes that may be treatable.

Delirium

Delirium is a sudden, severe confusion with rapid changes in brain function. Delirium develops over hours or days and is typically temporary and reversible. Delirium affects perception, mood, cognition, and attention. The most common causes of delirium in people with dementia are medication side effects, hypo or hyperglycemia (low or high blood sugar), fecal impactions, urinary retention, electrolyte disorders and dehydration, infection, stress, and metabolic changes. An unfamiliar environment, injury, or severe pain can also cause delirium.

Delirium is under-diagnosed in almost two-thirds of cases and can be misdiagnosed as depression or dementia. Since the most common causes of delirium are reversible, recognition enhances early intervention. Early diagnosis can lead to rapid improvement (Hope et al., 2014).

What is Delirium [2:51]

Source: Gateshead Health, National Health Service, England, U.K.

Depression

Depression is a common but serious mood disorder. Major depressive disorder is characterized by a combination of symptoms that interfere with a person’s ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy activities. Some people may experience only a single episode within their lifetime, but more often a person may have multiple episodes (NIMH, 2018).

Persistent depressive disorder is characterized by long-term (2 years or longer) symptoms that may not be severe enough to disable a person but can prevent normal functioning or feeling well. Psychotic depression occurs when a person has severe depression plus some form of psychosis, such as delusions or hallucinations. Psychotic symptoms typically have a depressive “theme,” such as delusions of guilt, poverty, or illness (NIMH, 2018).

Depression is very common in people with dementia. Almost one-third of long-term care residents have depressive symptoms and about 10% meet criteria for a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Despite this awareness, depression is undertreated in people with dementia. Depressive illness is associated with increased mortality, risk of chronic disease, and higher levels of supported care (Jordan et al., 2014).

Symptoms of depression can include:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness, guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Irritability, restlessness, or having trouble sitting still

- Loss of interest in once pleasurable activities, including sex

- Decreased energy or fatigue

- Moving or talking more slowly

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, making decisions

- Difficulty sleeping, early-morning awakening, or oversleeping

- Eating more or less than usual, usually with unplanned weight gain or loss

- Thoughts of death or suicide, or suicide attempts

- Aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems without a clear physical cause and/or that do not ease with treatment

- Frequent crying (NIH, 2017)