In this course we explain how dementia affects the brain and how Alzheimer’s disease differs from other types of dementia. We will review behaviors you might see in people with mild, moderate, and severe dementia and describe communication issues you will encounter at different stages. We offer techniques to address behavioral issues should they arise, and how to promote independence in all activities. Finally, we will discuss how to work with family members and caregivers who are caring for a person with dementia.

What Is Dementia?

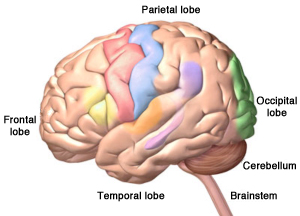

Dementia is caused by damage to a part of the brain called the cerebrum. The cerebrum fills up most of our skull and is divided into four lobes (one on each side of the head):

- Frontal

- Temporal

- Parietal

- Occipital

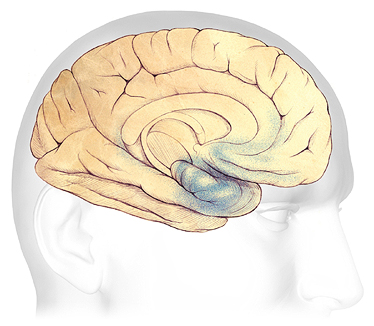

The Human Brain

The four lobes of the cerebrum, plus the cerebellum and the brainstem. Alzheimer’s disease starts in the temporal lobe, an area of the brain associated with memories and emotions. Copyright, Zygote Media Group, Inc. Used with permission.

The cerebrum is what makes us human—it allows us to think, make plans, talk, and understand. It controls our memories and emotions. It helps us reason, make decisions, and tell right from wrong. It also controls our movements, vision, and hearing. Many of these areas of the cerebrum are damaged by dementia.

Dementia is a group of symptoms impacting cognitive functions such as memory, judgment, reasoning, and social skills as well as interfering with the ability to function in daily life. Dementia is progressive, meaning it gets worse over time. It is a terminal illness, meaning it will eventually lead to death. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common kind of dementia.

When someone has dementia their thinking becomes less clear. Decisions are more difficult and safety awareness declines. People also get tired more easily. Emotions are also affected—that’s why people with Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia sometimes have difficulty controlling their emotions.

For people between the ages of 65 and 75, only about 5% will get any sort of dementia. For people over the age of 85, about 40% will experience some form of dementia. Even so, dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

How the Brain Works

The brain is the most complex organ in the human body. This three-pound mass of gray matter contains more than 90 billion nerve cells with about 150 trillion connections. The brain is at the center of all human activity—it regulates the body’s basic functions, allows us to interpret and respond to everything we experience, and shapes our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (NIDA, 2014).

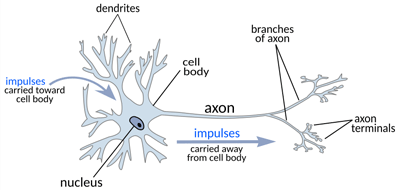

A nerve call (neuron) has three major parts: (1) the cell body—the part of the nerve cell that contains the nucleus and other organelles, (2) the axon—an elongated process that carries the nerve impulse away from the cell body, and (3) dendrites—which receive nerve impulses from neighboring nerves and transmit them to the cell body.

Left: Illustration of a healthy neuron showing the nucleus, cell body, dendrites, and axons. Source: WPClipArt.com. Used with permission. From http://www.wpclipart.com/medical/anatomy/cells/neuron/neuron.png.html. Right: A healthy nerve cell. Source: ADEAR, 2014. Public domain.

Neurons are electrically excitable, which allows them to receive, integrate, and send information. They are also plastic—which means they have the ability to modify their function in response to changes in input. Neurons communicate by releasing substances called neurotransmitters into the space between the neurons, called synapses. Once a neurotransmitter is released, it crosses the synapse and binds to receptors on adjacent neurons.

An image from the Human Connectome Project, which shows the abundance and complexity of white matter nerve fibers in the human brain. Human Connectome Project, National Institutes of Health. Used with permission.

Most neurons in the human brain are myelinated. Myelin, also called white matter, is a fatty substance that surrounds the axon and increases the speed and efficiency of the nerve impulse. Myelin insulates the axon, preventing leakage of the electrical impulse into the surrounding fluid as well as providing structural support for the elongated axon.

In certain brain regions, the white matter covering an axon is degraded or lost. This affects the brain’s ability to send and receive nerve impulses and to interact with neurons in other parts of the brain. When axons lose their ability to efficiently transmit a nerve signal, brain function is affected. Dementia interrupts the efficient function of these networks, affecting every aspect of a person’s life. Because white matter nerve fibers connect the different regions of the brain, even a little loss or breakdown of myelin can affect cognition. Take a look at the number and complexity of nerve fibers in the picture below get an idea of the millions of nerve fibers and billions of connections within the human brain.

How Does Dementia Affect the Brain?

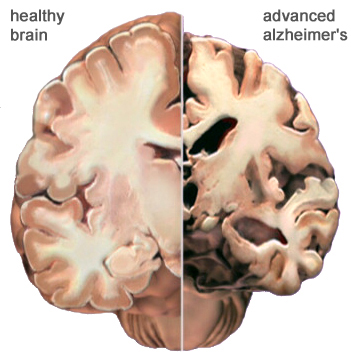

In Alzheimer’s disease, nerve cells in the brain die and are replaced by something called plaques and tangles. As the nerve cells die, the brain gets smaller. Over time, the brain shrinks, affecting nearly all its functions.

Dementia affects cognition—thinking, memory, judgment, learning, language comprehension, attitudes, beliefs, safety awareness, morals, and the ability to plan for the future. Dementia also affects motor and sensory functions such as balance, spatial awareness, vision, pain processing, and the ability to modulate (control) sensory input.

Dementia alters visual-spatial perception, and decreases the ability to recognize and avoid hazards (Eshkoor et al., 2014). It is also thought to impair working memory, a type of memory that promotes active short-term maintenance of information for later access and use. The decline in working memory also affects language comprehension and visuospatial reasoning (Kirova et al., 2015).

Normal Age-Related Changes

We all experience changes as we age. Some people become forgetful when they get older. They may forget where they left their keys. They may also take longer to do certain mental tasks. They may not think as quickly as they did when they were younger. These are called age-related changes. This is a normal part of aging—it not dementia.

Normal Brain Contrasted with AD Brain

A view of how Alzheimer’s disease changes the whole brain. Left side: normal brain; right side, a brain damaged by advanced AD. Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

People experiencing age-related changes can easily do everything in their daily lives—they can prepare their own meals, manage their finances, safely drive a car, go shopping, and use a computer. They understand when they are in danger and know how to take care of themselves. Even though they might not think or move as easily or quickly as when they were young, their thinking is normal—they do not have dementia.

In some older adults, memory problems are a little bit worse than normal age-related changes. This is known as mild cognitive disorder. Mild cognitive disorder isn’t dementia. You won’t generally see personality changes, just a little more difficulty than is normal with thinking and memory. For some people, mild cognitive impairment gets worse and develops into dementia, but this doesn’t happen with everyone.

The table below describes some of the differences between someone who is aging normally and someone who is experiencing the effects of dementia.

Normal Aging vs. ADRD | |

|---|---|

Normal aging | AD or other dementia |

Occasionally loses keys | Cannot remember what a key does |

May not remember names of people they meet | Cannot remember names of spouse and children—don’t remember meeting new people |

May get lost driving in a new city | Get lost in own home, forget where they live |

Can use logic (for example, if it is dark outside it is night time) | Is not logical (if it is dark outside it could be morning or evening) |

Dresses, bathes, feeds self | Cannot remember how to fasten a button, operate appliances, or cook meals |

Participates in community activities such as driving, shopping, exercising, and traveling | Cannot independently participate in community activities, shop, or drive |

Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Types of Dementia

Alzheimer’s disease typically starts by damaging an area of the brain called the hippocampus—the part of the brain responsible for new, short-term memories. This can cause a person with dementia, particularly someone with Alzheimer’s disease to forget something that happened just a moment ago. Although most types of dementia start in one part of the brain, eventually the entire brain will be affected.

It is common to describe Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other dementias, as progressing in “stages”. The stages are usually described as mild, moderate, and severe or early, middle, and late. Even though disease progression differs from person to person and varies depending on the type of dementia, we nevertheless associate certain symptoms and behaviors with these stages. The type of dementia, along with a person’s underlying medical condition, general health, family support, and co-morbid conditions affect how fast and how far the dementia progresses.

Mild Dementia

Brain Changes—Mild Dementia

In the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, before symptoms can be detected, plaques and tangles form in and around the hippocampus, an area of the brain responsible for the formation of new memories (shaded in blue). Source: The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

In the early, mild stage of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, plaques and tangles begin to cause damage within the temporal lobes, in and around the hippocampus. The hippocampus is part of the brain’s limbic system and is responsible for the formation of new memories, spatial memories and navigation, and is also involved with emotions.

Mild cognitive changes, which have likely been developing for several years begin to affect memory, decision-making, and complex planning. A person with mild dementia can still perform all or most activities of daily living such as shopping, cooking, yardwork, dressing, bathing, and reading and may even continue to work but will likely begin to need help with complex tasks such as balancing a checkbook and planning for the future.

Did You Know. . .

In a study by the National Institutes on Aging involving 62 participants, researchers used neuroimaging to assess changes in brain volume and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid levels.

- Immediate recall (the ability to remember events that occurred in the past few minutes) was the first memory function to show signs of deterioration.

- Delayed recall (the ability to remember more distant events) declined at a later stage of the disease, but at a more rapid rate than immediate recall.

This finding suggests that tests of immediate recall may be more useful for detecting Alzheimer’s during early stages of the disease, while tests of delayed recall may be better suited to tracking it at later stages (NIA, 2015).

Moderate Dementia

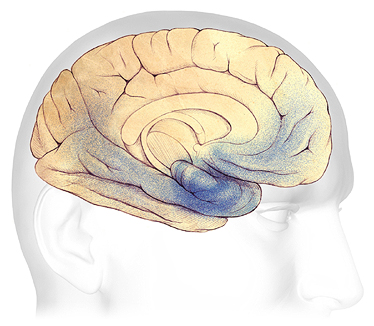

Brain Changes—Moderate Dementia

In mild to moderate stages, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) spread from the hippocampus forward to the frontal lobes. Source: The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses from the mild to moderate stage, plaques and tangles spread forward to the areas of the brain involved with language, judgment, and learning. Work and social life become more difficult as confusion increases. Speaking and understanding speech, the sense of where your body is in space, executive functions such as planning, logical thinking, safety awareness, and ethical thinking are affected. Many people are first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in this stage.

Severe Dementia

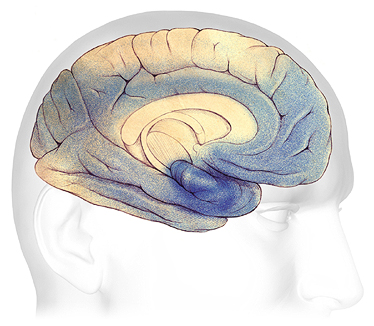

Brain Changes—Severe Dementia

In advanced Alzheimer’s, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) have spread throughout the cerebral cortex. Source: The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

In the later or severe stage, damage is spread throughout the brain. Because so many areas of the brain are affected, individuals may lose their ability to communicate clearly, to recognize family and loved ones, and to care for themselves.

People with severe dementia can lose all memory of recent events although they often still remember events from the past. They are easily confused, unable to make decisions, and cannot think logically. Speech, communication, and judgment are severely affected. Sleep disturbances and emotional outbursts are very common.

Stages of Other Types of Dementia

Although Alzheimer’s dementia worsens over time, other types of dementia may progress differently.

Because vascular dementia is caused by a stroke or series of small strokes, dementia may worsen suddenly and then stay steady for a long period of time—especially if the underlying cardiovascular causes are addressed.

In Lewy body dementia, which is often associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms—including cognitive abilities—can fluctuate drastically, even throughout the course of a day. Nevertheless, the dementia is progressive and worsens over time. In the later stages, progression is similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease.

Frontal-temporal dementia generally starts at an earlier age than Alzheimer’s disease. In the early stage—depending on which lobe of the brain is affected there are changes in personality, behavior, emotions, and judgment. There may also be early changes in language ability, including speaking, understanding, reading, and writing. Motor decline can also occur as the disease progresses. This is characterized by difficulties with movement, including the use of one or more limbs, shaking, difficulty walking, frequent falls, and poor coordination (NIH, 2014).