The Rhode Island General Assembly in 2019 passed an act that established a program within the Department of health to address Alzheimer’s disease. It determined that all state-licensed physicians and nurses must complete a one-hour course of instruction . . . on the diagnosis, treatment and care of patients with cognitive impairments including, but not limited to, Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

Rhode Island General Assembly, 2019

In this course we will discuss dementia. We will explain how dementia affects the brain. We will discuss how Alzheimer’s disease differs from other types of dementia. We will go over behaviors you will see every day in people with mild, moderate, and severe dementia. Finally, we will discuss communication issues you might see at different stages of dementia.

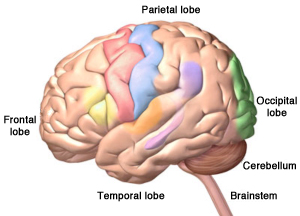

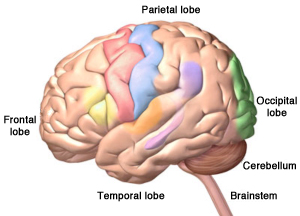

Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia are caused by damage to the brain. The part of the brain that is damaged in dementia is called the cerebrum. The cerebrum fills up most of our skull and is divided into four lobes:

- Frontal lobes: reasoning, judgement, motor control, planning, decision-making

- Temporal lobes: memory and emotion, hearing, language

- Parietal lobes: sensation, touch, temperature, pressure, pain

- Occipital lobes: visual processing, depth, distance, location of objects

The cerebrum is what makes us human—it does our thinking, remembering, talking, and understanding. It controls our emotions. It helps us reason things out and make decisions. It helps us tell right from wrong. It also controls our movements, vision, and hearing. Many of these areas of the cerebrum are damaged by dementia.

The Human Brain

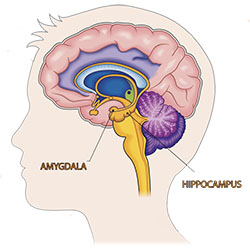

Left: The four lobes of the cerebrum, plus the cerebellum and the brainstem. Right: The cerebellum and brainstem are at the back of your head below the cerebrum. Alzheimer’s disease starts in the temporal lobe in an area called the hippocampus. Source: Copyright, Zygote Media Group, Inc. Used with permission.

Right: National Institutes of Health, Source: iStock/jambojam. Public domain.

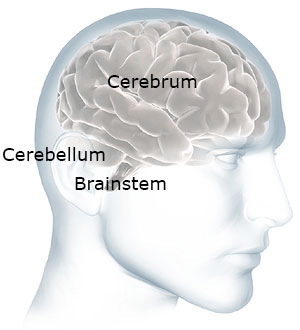

Our brain has two other important parts: the cerebellum and the brainstem. Touch the back of your head just above your neck. The cerebellum is right there. It controls coordination and balance.

Cerebellum and Brainstem

The cerebellum and brainstem are at the back of your head below the cerebrum.

Now move your hand a little down and stop before your get to your spine. The brainstem is right there—at the back of the head, above your spine. It connects the brain to the spinal cord. The brainstem oversees automatic things like breathing, digestion, heart rate, and blood pressure. The cerebellum and the brainstem are usually not affected by dementia.

What Is Dementia?

Dementia is a brain disease. It is progressive, meaning it gets worse over time. It is a terminal illness, meaning it will eventually lead to death. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common kind of dementia.

AD begins in the area of the brain that makes new memories, called the hippocampus. The hippocampus is the memory center of the brain, responsible for forming short-term memories. That’s why someone with AD forgets something that happened just a moment ago. This part of the brain also helps us associate memories with various senses, such as smell.

Other types of dementia begin in areas of the brain involved with thinking and reasoning. Although dementia can start in one part of the brain, eventually it will affect the entire brain.

Emotions are also affected when someone gets dementia. That’s why someone with Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia sometimes has difficulty controlling their emotions.

When someone has dementia, their thinking becomes less clear. Decisions are more difficult and safety awareness declines. People also tire more easily. Eventually, people with dementia lose the ability to take care of themselves. In the end, they may also lose their appetite and stop eating.

For people between the ages of 65 and 75, only about 5% will get any sort of dementia. For people over the age of 85, about 40% will experience some form of dementia. Even so, dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

How Does Dementia Affect the Brain?

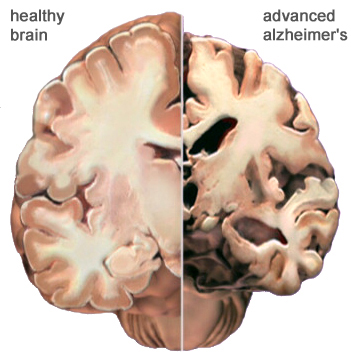

Dementia changes the entire brain. In Alzheimer’s disease, nerve cells in the brain are damaged by something called plaques and tangles. As the nerve cells die, the brain gets smaller. Over time, the brain shrinks, affecting nearly all its functions.

Normal Brain Contrasted with AD Brain

A view of how Alzheimer’s disease changes the whole brain. Left side: normal brain; right side, a brain damaged by advanced AD. Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

In Alzheimer’s disease, damage begins in the temporal lobe, in and around the hippocampus. The hippocampus a part of the brain that is responsible for new memories, spatial awareness, and control of emotions.

Dementia affects what are called executive functions: mental skills that include memory, thinking, and self-control. We use these skills to manage daily life. Dementia causes a gradual loss of executive functions and makes it hard to plan for the future, follow complex conversations, remember new things, and control emotions.

As the disease progresses, plaques and tangles spread to the front part of the brain (the temporal and frontal lobes). These areas of the brain are involved with language, judgment, and learning. Speaking and understanding speech, the sense of where your body is in space, and executive functions such as planning and ethical thinking are affected.

In severe Alzheimer’s disease, damage is spread throughout the brain. At this stage, because so many areas of the brain are affected, individuals lose the ability to communicate, to recognize family and loved ones, and to care for themselves.

Normal Age-Related Changes

We all experience changes as we age. Some people become forgetful when they get older. They may forget where they left their keys. They may also take longer to do certain mental tasks. They may not think as quickly as they did when they were younger. These are called age-related changes. This is a normal part of aging—it not dementia.

Age-related changes don’t affect a person’s life very much. Someone with age-related changes can easily do everything in their daily lives—they can prepare their own meals, manage their finances, safely drive a car, go shopping, and use a computer. They understand when they are in danger. They know how to take care of themselves. Even though they might not think or move as fast as when they were young, their thinking is normal—they do not have dementia.

The table below describes some of the differences between someone who is aging normally and someone who has some form of dementia.

Normal Aging vs. ADRD | |

|---|---|

Normal aging | AD or other dementia |

Occasionally loses keys | Cannot remember what a key does |

May not remember names of people they meet | Cannot remember names of spouse and children—don’t remember meeting new people |

May get lost driving in a new city | Get lost in own home, forget where they live |

Can use logic (for example, if it is dark outside it is night time) | Is not logical (if it is dark outside it could be morning or evening) |

Dresses, bathes, feeds self | Cannot remember how to fasten a button, operate appliances, or cook meals |

Participates in community activities such as driving, shopping, exercising, and traveling | Cannot independently participate in community activities, shop, or drive |

In some older adults, memory problems are a little bit worse than normal age-related changes. This is known as mild cognitive impairment, also called MCI.

Mild cognitive impairment isn’t dementia although you may see personality changes, as well as a little more difficulty than is normal with thinking and memory. For some people, mild cognitive impairment gets worse and develops into dementia, but this doesn’t happen with everyone.

Changes in behavior can occur in older adults and may be a risk factor for dementia. This is called mild behavioral impairment or MBI. Signs of MBI are apathy, mood swings, anxiety, agitation and aggression, social withdrawal, and abnormal thoughts (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021).

What Is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia. Nearly 6 million people in the United States suffer from Alzheimer’s. It is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and affects women more than men. About two-thirds of Americans caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease are women (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021).

The first thing you will notice in someone with Alzheimer’s disease is that they have trouble making new memories. This is called short-term memory loss. This happens because the part of the brain where new memories are formed becomes damaged by dementia.

Long-ago memories are stored in a part of the brain that is not affected by Alzheimer’s dementia. Especially at first, people can remember and talk about events from earlier times in their lives. As the dementia gets worse and more of the brain is affected, long ago memories might also start to fade.

Other Kinds of Dementia

Alzheimer’s disease isn’t the only cause of dementia. Unfortunately, there is no way to know for sure what type of dementia a person has. There is no blood test or x-ray that can diagnose Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia. The only sure way to know if someone had Alzheimer’s disease is to examine their brain after they die.

The symptoms are a little different in each type of dementia. It’s good to know the difference to help you understand why someone is acting the way they are.

Frontal-Temporal Dementia

Look at the picture of the brain below. Put your hands on your forehead. The part of your brain just behind your forehead is called the frontal lobe, you have one on each side of your forehead. Now slide your fingers from the front to the side of your head (your temple). This part of the brain is called the temporal lobe. You have 2 temporal lobes also—one on each side.

There is a type of dementia that affects this part of the brain. It is called frontal-temporal dementia. It is the most common type of dementia in people under the age of 60. It’s not nearly as common as Alzheimer’s and it starts at a much younger age. Frontal-temporal dementia can affect one side of the brain or both.

The Lobes of the Brain

Source: Copyright, Zygote Media Group, Inc. Used with permission.

We use the front part of our brain to make decisions, to tell right from wrong, and to control our emotions. We also use this part of the brain to plan for the future. People with dementia in this part of the brain have poor judgment and lose the ability to tell right from wrong. They also have less control over their behavior and have changes in personality.

In addition to behavioral changes, frontal-temporal dementia can affect a person’s language abilities. This is called aphasia and can cause difficulty understanding what another person is saying as well as difficulty with speech. A person’s speech might be hesitant, they may talk less that they did in the past, and they may have trouble naming things or understanding the meaning of words.

So, in the beginning, instead of difficulty with short-term memory like people with Alzheimer’s disease, a person with frontal-temporal dementia might start doing things that are confusing to their friends and family. They might steal, even though they have never stolen in the past. They might make inappropriate sexual remarks, swear, or engage in inappropriate sexual behaviors, even though they’ve never done these things in the past. Eventually, people with frontal-temporal dementia will lose their short-term memory.

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia is caused by reduced blood flow to the brain from hardening of the arteries, small strokes, high blood pressure, infections, and certain auto-immune diseases. When blood flow is reduced, the brain is deprived of oxygen and nutrients. Generally, vascular dementia doesn’t affect memory as much as Alzheimer’s because damage is often spread throughout the brain. Depending on size and location, damage can be mild or severe and can affect more than one area of the brain.

Vascular dementia can cause mood swings, depression, irritability, and anxiety. It can also affect judgment—but usually not as strongly as in someone with frontal-temporal dementia. It is hard to say that vascular dementia leads to certain symptoms that are worse/or less than other types of dementia because the symptoms tend to be strongly dependent on where the strokes have occurred.

You might have cared for more than one patient with vascular dementia because many older adults have high blood pressure that isn’t under good control. You may also see vascular dementia in someone who has had a stroke.

Lewy Body Dementia

Lewy body dementia is less common than Alzheimer’s dementia, frontal-temporal dementia, or vascular dementia. It is responsible for a little less than 5% of all cases of dementia. People with Parkinson’s disease can have this type of dementia.

In Lewy body dementia, abnormal clumps of alpha-synuclein (Lewy bodies) are scattered throughout the cortex, brainstem, and midbrain. The location of these clumps influences the symptoms, which vary from person to person.

People with Lewy body dementia may have problems with memory, which can be mistaken for Alzheimer’s disease. They may have movement difficulties that are similar to Parkinson’s disease (slow movement, tremors, difficulty walking). They can also have visual hallucinations, mental fluctuations (drowsiness, staring into space, long naps, disorganized speech), and sudden confusion. These symptoms can come and go throughout the day.

People with Lewy body dementia can also experience visuospatial difficulties. This is more than just visual difficulties—they can have problems processing where objects are in space, including their own arms and legs. Other visuospatial difficulties can include trouble with depth perception, judging distance, and understanding the distance between two objects. It also involves difficulties with math and reading. We use visuospatial skills to dance, make sense of the shape of numbers and letters, and to keep from bumping into someone passing us in the hallway.

Lewy body dementia can also affect a person’s sleep and cause a person to suddenly faint or pass out. This means a person with Lewy Body dementia is at high risk for unexpected falls.

Some Common Types of Dementia | |

|---|---|

Type of dementia | Characteristics and symptoms |

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | Loss of short-term memory Behavioral changes, apathy, depression, anxiety Personality and behavior changes Mood swings Difficulty communicating and understanding speech |

Frontal-temporal dementia | Changes in behavior Poor judgment Loss of moral reasoning Loss of inhibition Changes in speech and communication |

Vascular dementia | Memory affected but less than in AD Poor judgment Mood changes—more than in AD Apathy Irritability |

Dementia with Lewy bodies | Visual hallucinations Sleep disturbance Motor control problems Mental fluctuations Visuospatial difficulties |

Diagnostic Guidelines

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is based on symptoms; no test or technique that can diagnose dementia. To guide clinicians, in 2011 the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) published updated diagnostic guidelines, which are intended to provide a deeper understanding Alzheimer’s disease than earlier guidelines. The 2011 (latest) guidelines:

- Recognize that Alzheimer’s disease progresses on a spectrum with three stages: (1) an early, preclinical stage with no symptoms; (2) a middle stage of mild cognitive impairment; and (3) a final stage marked by symptoms of dementia. Cognitive decline is gradual and progressive.

- Expand the criteria for Alzheimer’s dementia beyond memory loss as the first or only major symptom and recognize that other aspects of cognition, such as word-finding ability or judgment, may become impaired first. Other cognitive changes can include changes in:

- Episodic memory

- Executive functioning

- Visuospatial abilities

- Language functions

- Personality and/or behavior

- Reflect a better understanding of the distinctions and associations between Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s dementias, as well as between Alzheimer’s and disorders that may influence its development, such as vascular disease, delirium, or stroke.

- Recognize the potential use of biomarkers—indicators of underlying brain disease—to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. However, the guidelines state that biomarkers are almost exclusively to be used in research rather than in a clinical setting. (NIA-AA, 2020)

Since the publication of the 2011 guidelines, researchers have increasingly come to understand that cognitive decline in AD occurs continuously over a long period, and that progression of biomarker measures* is also a continuous process that begins before symptoms are evident. The disease is now regarded as a continuum rather than three distinct clinically defined stages (Jack et al., 2018).

*β amyloid deposition, pathologic tau, and neurodegeneration / neuronal injury.

A 2018 update of the 2011 NIA-AA diagnostic guidelines added a numerical clinical staging scheme. This staging scheme reflects the sequential evolution of AD from an initial stage characterized by the appearance of abnormal biomarkers in asymptomatic individuals. As biomarker abnormalities progress, the earliest subtle symptoms become detectable. Further progression of biomarker abnormalities is accompanied by progressive worsening of cognitive symptoms, culminating in dementia (Jack et al., 2018).

The numerical clinical staging scheme is as follows:

- Performance within expected range on objective cognitive tests.

- Normal performance within expected range on objective cognitive tests. (Transitional cognitive decline: Decline in previous level of cognitive function, which may involve any cognitive domains.

- Performance in the impaired/abnormal range on objective cognitive tests.

- Mild dementia.

- Moderate dementia.

- Severe dementia. (Jack et al., 2018)

In 2018 an Alzheimer’s Association workgroup lead by Alireza Atri published a report describing the need for clinical practice guidelines for use in primary and specialty care settings. The guidelines build on the NIA_AA guidelines but add a clinical component for the evaluation of cognitive impairment thought to be related to Alzheimer’s disease or a related type of dementia.

Key components include:

- All middle-aged or older individuals who self-report or whose care partner or clinician report cognitive, behavioral or functional changes should undergo a timely evaluation.

- Concerns should not be dismissed as “normal aging” without a proper assessment.

- Evaluation should involve not only the patient and clinician but, almost always, also involve a care partner (e.g., family member or confidant). (Atri, 2019)

Neuroimaging and CSF Biomarkers

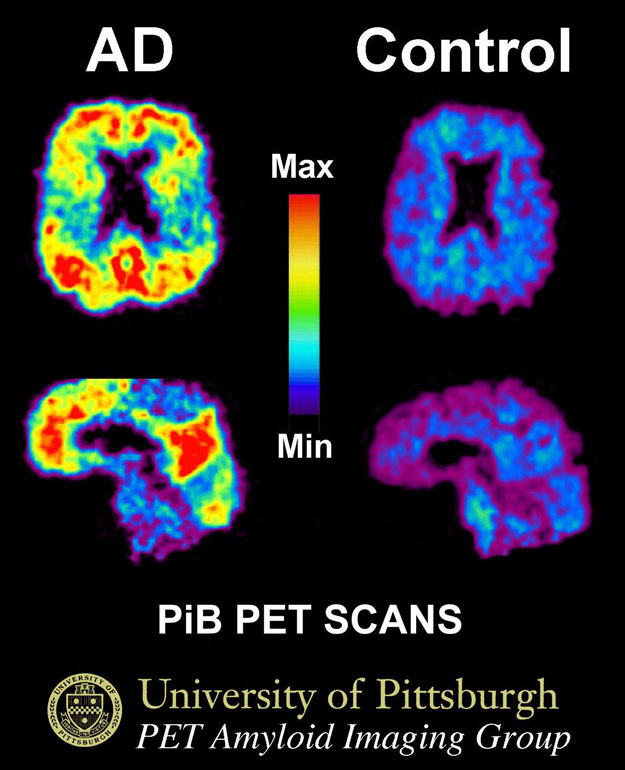

PET Scans Showing PiB Uptake

This image shows a PiB-PET scan of a patient with Alzheimer's disease on the left and an elder with normal memory on the right. Areas of red and yellow show high concentrations of PiB in the brain and suggest high amounts of amyloid deposits in these areas. Source: Klunkwe, own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Neuroimaging is increasingly being used to assist with early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias by detecting visible, abnormal structural and functional changes in the brain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide information about the shape, position, and volume of the brain tissue and is being used to detect brain shrinkage, which is related to excessive nerve death. Positron emission tomography (PET) uses a radioactive dye called PiB to detect the presence of beta amyloid plaques in the brain.

CSF biomarkers are measures of the concentrations of proteins in cerebral spinal fluid from the lumbar sac that reflect the rates of both production (protein expression or release/secretion from neurons or other brain cells) and clearance (degradation or removal) at a given point in time.