Lasting just over a year, the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic stands as a lasting reminder of what happens when governments and their citizens fail to meet a crisis head on. From our perch today, as we brace for the coronavirus’ inevitable spread, the missteps of 1918 seem eerily prescient: A lack of leadership from Washington, with the gaps filled unevenly at the state and local levels.

Public officials who either lied, dissembled or made up facts. Hucksters who used popular media to misinform the public and make a quick buck in the process. Public health infrastructure that was inadequate to the challenge. And ordinary citizens who often refused to heed the warning of experts.

Joshua Zeitz

Politico magazine, March 17, 2020

Influenza occurs in two distinct patterns: pandemic and seasonal. Pandemic influenza results from the emergence of a new influenza A virus to which the population possesses little or no immunity and that can occur at any time of year. Seasonal influenza is usually caused by influenza A or B viruses and generally occurs each year during a specific time of the year.

While outbreaks of influenza may be traced as far back as 412 B.C.E., the first pandemic, or worldwide epidemic, that clearly fits the description of influenza occurred in 1580. It began in Asia and spread to most of the rest of the world, affecting nearly all of Europe in just six weeks. At least four influenza pandemics occurred in the nineteenth century, followed by three more in the twentieth century and one in this century.

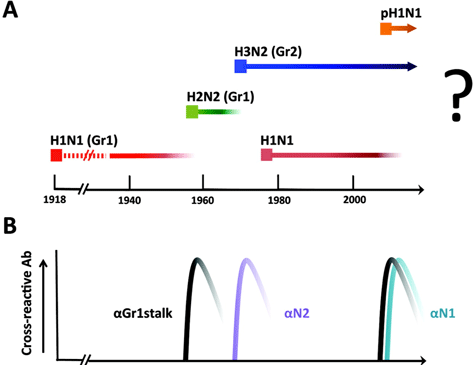

In the twentieth century, the most devastating example of a new influenza subtype emerging in the human population occurred in 1918. The virus contained a subtype 1 hemagglutinin protein (H1) and a subtype 1 neuraminidase protein (N1). After the 1918 pandemic, H1N1 variants circulated for 39 years before being replaced by an H2N2 virus in 1957. The H2N2 virus was prevalent for only 11 years until 1968, when it was replaced by an H3N2 virus (Palese & Wang, 2011). In 2009, a new strain of H1N1 influenza emerged and caused a worldwide pandemic in which an estimated 280,000 people died.

Influenza A Viruses Circulating in the Human Population

(A) H1N1 indicates virus with hemagglutinin subtype 1 and neuraminidase subtype 1. H2N2 and H3N2 indicate viruses with hemagglutinin subtype 2 and neuraminidase subtype 2 and hemagglutinin subtype 3 and neuraminidase subtype 2, respectively. pH1N1 indicates the novel swine origin virus first isolated in 2009. (B) Antibody response in the human population, which the authors propose to have contributed to the elimination of existing seasonal influenza virus strains. Source: Palese & Wang, 2011.

How Influenza Pandemics Occur—Video (3:23)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DdFCx8jbesQ

The Mother of All Pandemics: 1918–1919

The influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 killed more people than the Great War, known today as World War I, at somewhere between 20 and 40 million people. It has been cited as the most devastating epidemic in recorded world history. More people died of influenza in a single year than in the four years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351. Known as “Spanish Flu” or “La Grippe,” the influenza of 1918–1919 was a global disaster.

Molly Billings, 2005

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918

The 1918 influenza pandemic, caused by an H1N1 influenza subtype came on suddenly in March of 1918 and spread rapidly throughout the world. In the United States the first reports came from public health officials in Haskell County, Kansas, who reported “18 cases of influenza of a severe type.” By June the virus had spread from the United States to Europe, where it quickly moved from the military to the civilian population. From there, the disease circled the globe—to Asia, Africa, South America, and, back again, to North America.

The effect of the influenza epidemic was so severe that the average lifespan in the United States was depressed by 10 years (Billings, 2005). The “Spanish influenza” of 1918 is estimated to have hit nearly a third of the world’s population. Conditions at the end of World War I likely contributed to the mortality (Nicholls, 2006).

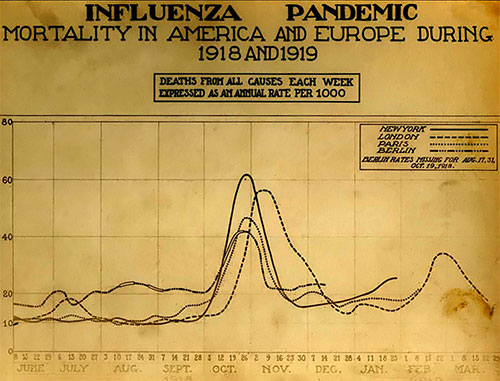

The 1918 pandemic occurred in three waves. The first wave was seen when mild influenza erupted in the late spring and summer of 1918. The second wave occurred with an outbreak of severe influenza in the fall of 1918 and the final wave hit in the spring of 1919. A physician stationed at Fort Devens, outside Boston, reported in late September 1918:

This epidemic started about four weeks ago, and has developed so rapidly that the camp is demoralized and all ordinary work is held up till it has passed. . . . These men start with what appears to be an ordinary attack of La Grippe or Influenza, and when brought to the Hosp. they very rapidly develop the most viscous type of Pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission they have the Mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the Cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible. One can stand it to see one, two, or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies sort of gets on your nerves. We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day, and still keeping it up. There is no doubt in my mind that there is a new mixed infection here, but what I don’t know.

Influenza Ward During the 1918–1919 Epidemic

Source: Office of the Public Health Service Historian.

Few Tools to Fight the Pandemic

[Material in this section is from HHS, 2009 unless otherwise cited.]

Unfortunately, few tools were available to either prevent the spread of influenza or treat patients during the 1918–1919 pandemic. A variety of remedies were tried, many of which could be found in local drugstores. Patent medicines (medicines whose ingredients were secret and trademarked) were still in widespread use in 1918. Among these medicines, Vicks Vapo-Rub, atropine capsules (belladonna), and a host of other treatments were especially common. In terms of curing or treating influenza symptoms, these remedies did little to nothing (HHS, 2009).

Patent Medicine Label

Drug advertisers routinely promised quick and painless cures. Source: National Library of Medicine.

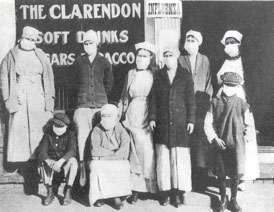

At the time, most physicians believed that influenza was caused by a bacillus. Nevertheless, many practitioners resorted to treatments derived from older medical theories. These treatments included causing patients to sweat by wrapping them in blankets or cupping them to remove excess blood (HHS, 2009). People were also encouraged to wear masks, which had little effect.

Because patients experienced symptoms not traditionally associated with influenza, physicians found the disease especially difficult to diagnose in 1918. In the early stages of the pandemic, many physicians and scientists even claimed that influenza patients were suffering from cholera or bubonic plague, not influenza (HHS, 2009).

People Wearing Masks to Ward Off the Flu

During the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic, people dutifully wore masks, which provided only a very limited protection against the influenza virus. Source: Office of the Public Health Service Historian.

During the fall of 1918, researchers from the Public Health Service began looking for a vaccine. They were joined by researchers in many other countries. These researchers developed a range of vaccines that were then tested in communities all over the world. None of these vaccines proved effective. While researchers placed their hope in vaccines, many politicians and physicians came to believe that the spread of the disease could be contained by quarantines and bans on public gatherings (HHS, 2009).

Across the United States, cities and counties began to require or recommend that citizens wear gauze masks. Unfortunately, while masks are highly effective at preventing diseases that are caused by bacteria, they are less effective in providing protection against viral diseases. As a result, even in communities where the wearing of masks was mandatory, influenza could not be contained. Public officials also sought to limit influenza by banning spitting in public places and demanding that those who sneezed covered their mouths.

Red Cross Volunteers in Boston, Massachusetts, 1918

Massachusetts had been drained of physicians and nurses due to calls for military service, and no longer had enough personnel to meet the civilian demand for healthcare during the 1918 flu pandemic. Governor McCall asked every able-bodied person across the state with medical training to offer their aid in fighting the epidemic. Boston Red Cross volunteers assembled gauze influenza masks for use at hard-hit, Camp Devens in Massachusetts. Source: CDC Historical Image Gallery.

Early Symptoms, Recovery, and Relapse

During the 1918 pandemic, early symptoms included a temperature in the range of 102°F to 104°F. Patients experienced a sore throat, exhaustion, headache, aching limbs, bloodshot eyes, a cough, and occasionally a violent nosebleed. Some also suffered from digestive symptoms such as vomiting or diarrhea. Many patients who experienced these symptoms made a full recovery, only to suffer a relapse. Their temperatures, which had fallen, rose again and they now experienced serious respiratory problems. In some cases, these patients also experienced massive pulmonary hemorrhage. After death, pathologists found these victims to have swollen lungs and oversized spleens (HHS, 2009).

The Spanish Influenza

Chart showing mortality from the 1918 influenza pandemic in the United States and Europe, peaking in October and November 1918 and again in February and March of 1919. Source: Courtesy of the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Origin of the 1918 Pandemic Strain

The 1918 pandemic strain of influenza is thought to have originated in China in a rare genetic shift of the influenza virus. The recombination of its surface proteins created a virus novel to almost everyone (Billings, 2005).

Lung Tissue from Influenza Patient

Lung from deceased influenza patient similar to that used to extract RNA from the 1918 killer strain. Source: Courtesy of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C.

In the late 1990s, researchers found isolates of the 1918 pandemic virus in the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lungs of an American serviceman. They subsequently retrieved further samples of this deadly virus from a second soldier, and also from a flu victim exhumed from a frosty mass grave in Alaska. The genetic sequencing of the 1918 HIN1 virus was completed in 2005 (Nicholls, 2006).

The sequencing of the 1918 pandemic strain resulted in a key finding. Each segment is more similar to avian viruses than to segments from any human strains. This suggests that the virus did not emerge through reassortment of genetic material but evolved directly via mutation from an avian virus (Nicholls, 2006).

In the end, more than 50 million people throughout the world died as a result of the influenza pandemic. An estimated 675,000 people died in the United States. More people died from influenza than died during World War I.

Online Resource

We Heard the Bells—1918 Flu Pandemic: Video (8 min)

http://www.flu.gov/video/2010/01/we-heard-the-bells.html