Suicide is not limited to any one age or gender but nevertheless rates do vary among these groups. For teens, young adults, and middle-aged adults ,suicide has nearly tripled since the 1940s. Although suicide attempts are more frequent among young adults, older men and women have the highest rates of suicide in almost all countries.

Teens and Young Adults

Throughout the United States, suicide is the second leading cause of death for youth between the ages of 10 and 24. Teens ager 10 to 17 have the highest rate of suicidal attempts of any age group. Suffocation accounts for nearly half of suicide deaths, closely followed by firearms (CDC, 2019).

Family history of suicide, depression, mental health problems, incarceration, access to lethal means, alcohol and drug abuse, and suicidal behavior by others can put a young person at increased risk for suicidal behaviors. An increased risk of suicide has also been linked to moving frequently, due to fewer opportunities for developing healthy social connections and supports.

Certain youth are at higher risk than others. Boys are more likely than girls to die from suicide; however, girls are more likely than boys to attempt suicide. Native American/Alaskan Native youth have the highest rates of suicide-related fatalities. Hispanic youth are more likely to report attempting suicide than their black, white, and non-Hispanic peers.

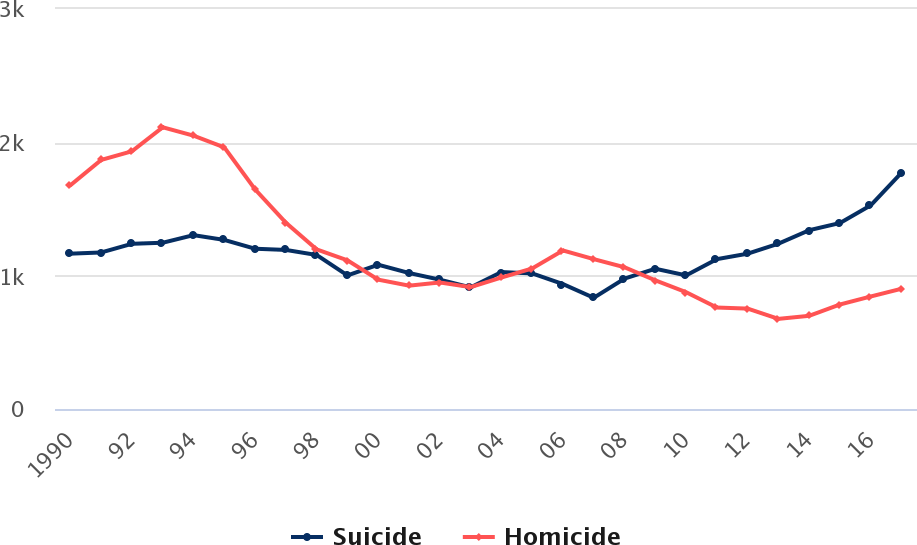

Among youth aged 10 to 17, there are many more suicides than homicides. Although in the 1990s homicides significantly outnumbered suicides, in the last five years nearly twice as many youths died as a result of suicide than homicide (OJJDP, 2019).

Number of Suicide and Homicide Victims Ages 10–17, 1990–2017

Homicide victims ages 10 to 17 outnumbered youth suicide victims through 1999. More recently, however, the trend reversed as suicides outnumbered

homicides annually since 2009. By 2017, nearly twice as many youth died as a result of suicide than homicide.

Source: OJJDP, 2019.

Middle-Aged Adults (45–64 years)

For middle-aged adults, suicide is the eighth leading cause of death. Although middle-aged adults have a lower percentage of suicidal attempts than younger adults they have higher rates of death from suicide. The death rate from suicide has significantly increased in recent years, and is higher than for any other age group. This increase is seen for both middle-aged males and females (CDC, 2019).

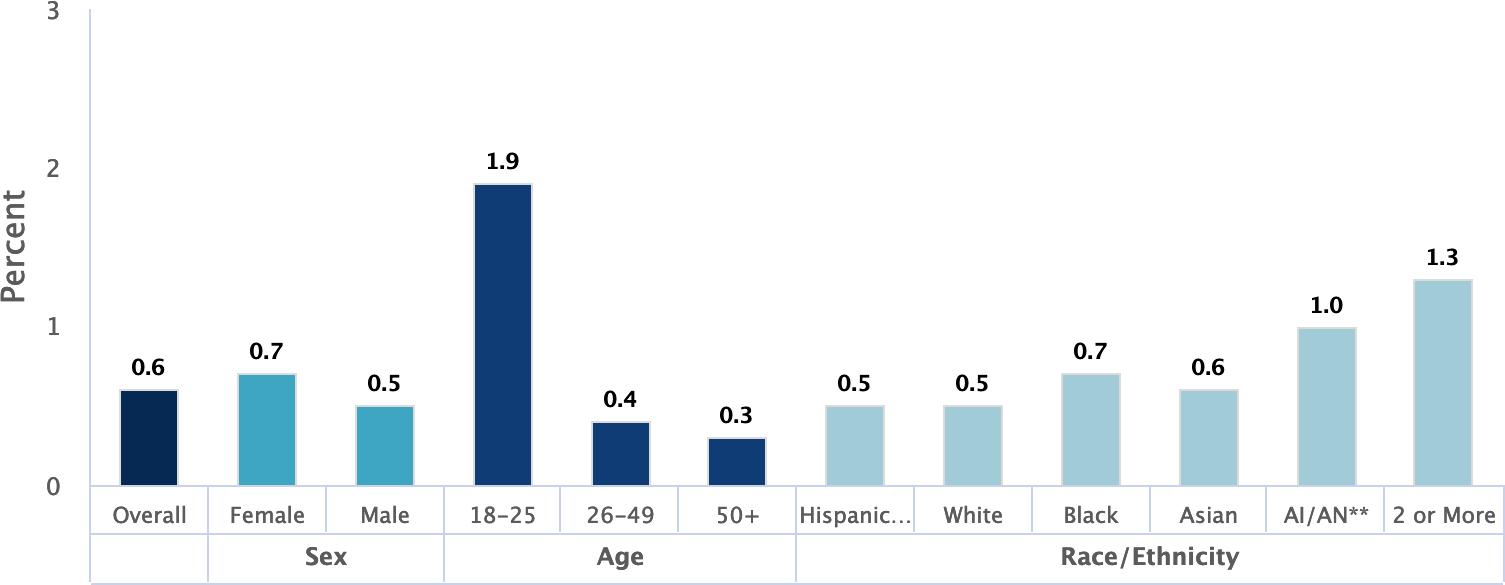

Past Year Prevalence of Suicide Attempts Among U.S. Adults (2017)

Source: Data courtesy of SAMHSA. Chart, NIMH, 2019 figure 8.

Older Men and Women

Physical illnesses and physical disability are strongly associated with suicide attempts in older adults. Limited social connectedness, changes in cognition, loss of control, social exclusion, and loneliness are associated with suicidal ideation, non-fatal suicidal behavior, and suicide. Strong risk factors for death by suicide include death of a spouse or partner, bereavement, having a mental disorder, and experiencing physical illness. Research has identified three clusters among patients aged 80 and older who died by suicide: (1) married or widowed patients, (2) individuals who were living alone or socially isolated, and (3) people suffering from dementia or depression (Conejero et al., 2018).

Gender Differences

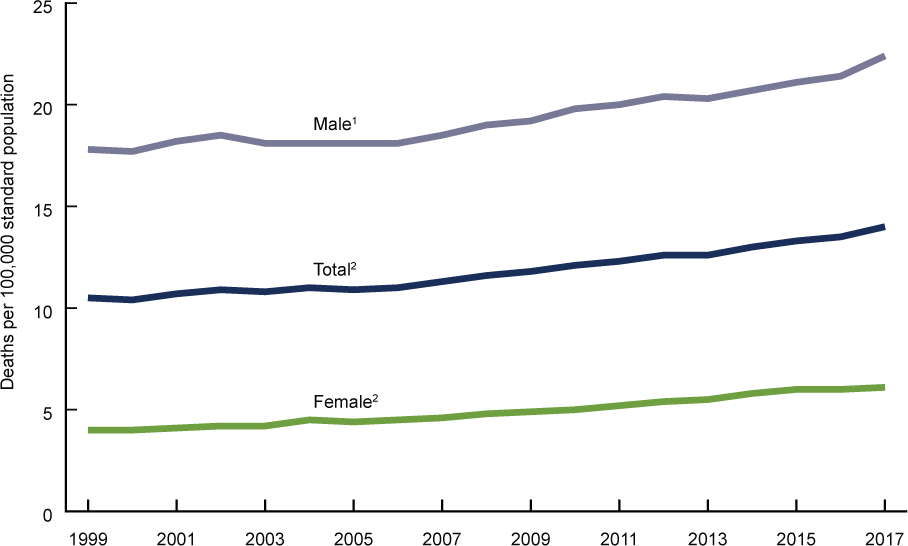

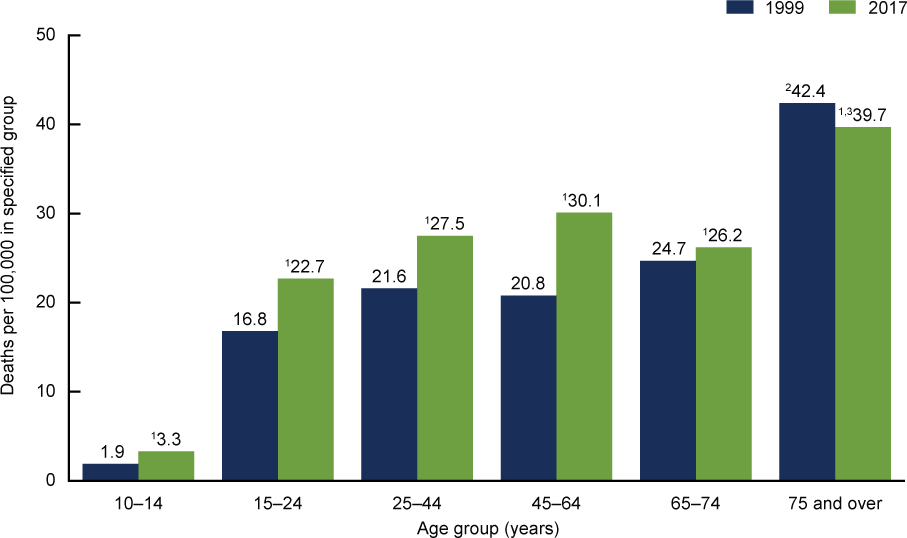

From 1999 through 2017, suicide rates increased for both males and females. During this period, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 33%. Compared with rates in 1999, suicide rates in 2017 were higher for males and females in all age groups from 10 to 74 years (CDC, 2018b).

Age-Adjusted Suicide Rates, by Sex (United States, 1999–2017)

1Stable trend from 1999 through 2006; significant increasing trend from 2006 through 2017, p < 0.001.

2Significant increasing trend

from 1999 through 2017 with different rates of change over time, p < 0.001.

Source: CDC, 2018b Figure 1.

Although women are more likely than men to attempt suicide, men are likely to use deadlier methods. Suicide is most common in women aged 35 to 64 years, peaking in women aged 45 to 54 years. Starting at about 50 years of age, suicide rates among women tend to diminish progressively, until old age, when rates start increasing again (Mendez-Bustos et al., 2013).

Data from the Nurses’ Health Study indicated that suicide rates among middle-aged women in the United States have increased by more than 30% in recent years, exceeding even the relative increases observed among middle-aged men. However, women who were socially well integrated* had a more than 3-fold lower risk for suicide over 18 years of followup (Tsai et al., 2015).

*Social integration was measured with a 7-item index that included marital status, social network size, frequency of contact with social ties, and participation in religious or other social groups (Tsai et al., 2015).

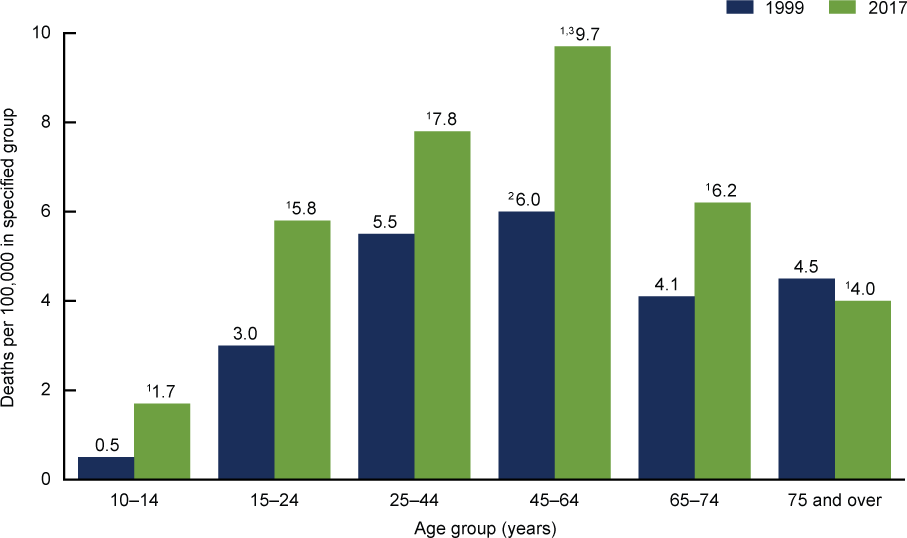

Suicide Rates for Females, by Age Group (United States, 1999 and 2017)

1Significantly different from 1999 rate.

2Significantly higher than rates for all other age groups in 1999.

3Significantly

higher than rates for all other age groups in 2017.

Source: CDC, 2018b Figure 2.

In men, social withdrawal, anger, and reduced problem solving capacity may be signs of suicidal ideation. Statements of suicidal intent, calmness, anger, apathy, hopelessness, risk-taking, and appearing “at peace” may indicate someone who is planning a suicide attempt. Signs preceding death by suicide include desperation and frustration in the face of unsolvable problems, helplessness, worthlessness, statements of suicidal intent, and emergence of a positive mood state (Hunt et al., 2017).

Male participants in a 2015 Australian study reported experiencing some or all of the following four factors in the development of suicidality:

- Periods of depressed or disrupted mood

- Conceptions of masculinity that strongly influenced decision-making (such as stoicism)

- Social isolation and use of avoidant coping strategies

- At least one, but often many, personally meaningful stressors (Player et al., 2015)

Trends in Suicide Rates Among Males (United States, 1999 and 2017)

1Significantly different from 1999 rate.

2Significantly higher than rates for all other age groups in 1999.

3Significantly

higher than rates for all other age groups in 2017.

Source: CDC, 2018b Figure 3.

Retired Builder

A 69-year-old Caucasian man—a retired builder with a medical history of chronic depression—was brought to hospital after a failed suicide attempt. The attempt consisted of self-asphyxiation with car exhaust fumes and shooting himself three times with a three-inch nail gun. The initial shot was directed upward through the submental triangle behind the chin. It pierced his tongue, upper denture plate, and hard palate, effectively pinning his mouth shut. The subsequent two shots were fired into the fourth intercostal space immediately left of the sternum.

On admission to the ED the patient was distressed but hemodynamically stable. An examination revealed nail gun entry wounds on his left anterior chest wall over the precordial area, and at the submandibular area under his chin, pinning his mouth closed. The nails within the thorax could not be confidently located on chest X-ray; however, transthoracic echocardiography suggested a nail had possibly penetrated into the right ventricle. There was no associated pericardial effusion. The patient was immediately transferred to the operating room where preparations for an exploratory midline sternotomy and thoracotomy were made.

The potential for rapid hemodynamic deterioration due to the intrathoracic penetrating injury required urgent surgical exploration. The uncertainty in the location of the intrathoracic nails meant the exact nature of the surgical repair was not defined and provision was made for lung separation. In this case, the chest x-ray failed to allow an adequate view of the nail within the thorax. Although transthoracic echocardiography suggested the nail had penetrated the right ventricle, the exact location of the nail was not clear.

Cardiopulmonary bypass was initiated to facilitate surgical exposure. During cardiopulmonary bypass, the endobronchial balloon was deflated, as lung isolation was not required, and cardiac repair was completed uneventfully. Removal of the nail from his mouth required a small incision into the hard palate and extraction using surgical pliers, removing the nail from his hard palate, upper denture, and tongue. The patient made an excellent recovery and was discharged five days later to a psychiatric community hospital for ongoing psychological rehabilitation.

Source: Lim et al., 2013.

Suicide Among Nurses

The loss of a nurse colleague to suicide is more common than generally acknowledged and is often shrouded in silence, at least in part due to stigma related to mental health and its treatment. Compared with what is available for physicians, a standard procedure for how to handle the suicide of a nurse colleague does not exist. Because of this, unit managers are left to develop a recovery plan independently to support staff in their grief and recovery (Davidson et al., 2018).

Several international studies, although outdated, nevertheless describe factors that are relevant today to nurses in the United States: ethical conflicts, organizational deficits, role ambiguity, shift work, social disruption of families due to work hours, team conflict, and workload. In two U.S. studies performed using data from the Nurses’ Health Study, a combination of work and home stress, smoking, and Valium use were identified as suicide risk factors (Davidson et al., 2018).

A critical review of nine additional studies found that collective risk factors leading to nurse suicide included access to lethal means, depression, knowledge of how to use lethal doses of medications and toxic substances, personal and work-related stress, smoking, substance abuse, and under-treatment of depression (Davidson et al., 2018).

Nursing is demanding and stressful work, with frequent exposure to human suffering and death, and burnout is common. Many nurses point to daily ethical issues and ethics-related stress, perceive limited respect in their work, and are increasingly dissatisfied with their work situations (Davidson et al., 2018).

Despite knowledge that nurse suicide exists, the occurrence of nurse suicide is shrouded in silence, avoidance, and denial. No public data identifying a national nurse suicide rate is available, yet data on suicide rates are readily available for physicians, teachers, police officers, firefighters, and military personnel. Transparency is complicated by a lack of standardized reporting of death by suicide. Reporting characteristics vary from county to county; some do not include occupation. In states that do report occupation, the occupation code is usually entered in free text, resulting in difficulty constructing a methodology for accurate data analysis (Davidson et al., 2018).

Soana Starts a New Job

I was hired on the ICU night shift after having moved to a new town. The culture was quite different from my previous hospital. The night nurses were noticeably less collaborative, with more of a “get your own work done so you can sit and read” attitude. I was used to a culture where “no one sits down until everyone can sit down.”

The day shift seemed different, but maybe that was because the day shift supervisor Penny was a bright ray of light. I remember Penny very well. She looked like a perfect West Coast girl, tan, with beautiful white teeth sparkling in her warm smile; [she was] energetic, always warm and friendly, with a hint of mischief. A consummate professional, Penny was a fierce patient advocate and was loved by the staff, physicians, and families. I wanted to be like Penny. Her leadership on the day shift was missing in my night shift colleagues.

I’d been at my new job for about 6 months when I received a call asking if I could come in early to start my shift. There had been a tragedy among the staff and there were nurses who were unable emotionally to finish their shifts. When I asked what had happened, the charge nurse told me Penny had died. They were looking for relief to allow the grieving nurses to go home.

When I arrived, everyone in the ICU was red-eyed from crying and looking shell-shocked. When I asked what happened to Penny, I was told she was found dead at her home by her husband, from whom she had recently separated. I was shocked and saddened by the news but, since I only knew Penny from our brief encounters at staff meetings and change of shift, I was able to contain my own emotions enough to relieve one of her closest colleagues.

Weeks later, after the funeral and many mournful days in our unit, we were told Penny’s death was due to an intentional injection of a neuromuscular blocking agent. She had removed the drugs from the unit’s secured drug storage locker the day before. Only those very close to her knew of her marital problems. No one at work would ever suspect Penny was suffering so much in her personal life. She never let her pain show. Interactions with Penny were always upbeat and positive.

We all missed Penny terribly in those months after her suicide. We asked ourselves how we could have missed or misjudged her degree of despair over her failing marriage. Unfortunately, the culture on nights in ICU did not improve and I requested a transfer to the surgical trauma unit on the opposite side of the hospital. The ICU just wasn’t the same without Penny and the staff was still struggling with emotions.

I’ll never forget Penny—her wonderful personality and her gifts as a nurse and leader. I still struggle with how someone with so many caring colleagues, and access to support and help, could have seen no hope in her situation.

I’ve since learned that suicide is a complex and dynamic emotional condition. There are stigmas that need to be overcome so nurses (and all people) suffering from depression, hopelessness, and despair know they can seek help and will not be judged. Maybe Penny thought because she was a nurse she should be able to handle her life situation and depression on her own.

Source: Davidson et al., 2018 (edited for length).