We have long known that diversity, including gender diversity, is key to effective, innovative organizations. In the for-profit world, diversity relates directly to sales and profits. In global health, where organizations are striving to create a healthier world, it is even more critical to embrace diversity as a mechanism to maximize our ability to deliver on our missions.

Catherine Ohura

The Global Health Innovative Technology Fund

Serving a diverse population and achieving cultural competency in healthcare is the stated goal of most U.S. healthcare organizations. However, achieving this goal in today's healthcare environment, filled with diverse patient and provider populations, is no easy task. This creates the ideal breeding ground for conflict and misunderstanding, which can result in tension among the staff and inferior patient care (Galanti, 2019).

To provide the best possible care for all patients, regardless of race, gender, or ethnic origin, culturally competent education is essential. It is not possible to know everything about every culture, but the first important step is an awareness of the fact that different cultures have different rules of appropriate behavior (Galanti, 2019).

Workforce Diversity

A racially and ethnically diverse healthcare workforce provides better access and care for underserved populations, promotes research that focuses on marginalized communities, and better meets the health needs of an increasingly diverse population. People of color, however, remain underrepresented in several health professions, despite longstanding efforts to increase diversity (AHRQ, 2021, December).

Several studies have shown the importance of a diverse medical workforce. Black and Hispanic physicians are more likely to care for underserved populations, including racial minorities and uninsured patients. Physician diversity has also been linked to better patient outcomes in primary care (Lett, Orji, and Sebro, 2018).

Gender diversity is also important. Women currently account for three-quarters of full-time, year-round healthcare workers. Although the number of men who are dentists or veterinarians has decreased over the past two decades, men still make up more than half of dentists, optometrists, and emergency medical technicians/paramedics, as well as physicians and surgeons (AHRQ, 2021, December).

Decolonization, Inclusion, and Equity

The COVID-19 pandemic, the Black Lives Matter and Women in Global Health movements, and ongoing calls to decolonize* global health have all created space for uncomfortable but important conversations that reveal serious asymmetries of power and privilege that permeate all aspects of global healthcare systems (Abimbola et al., 2021).

*Decolonize: To free a people, profession, or area from colonial status: to relinquish control of a subjugated people or area.

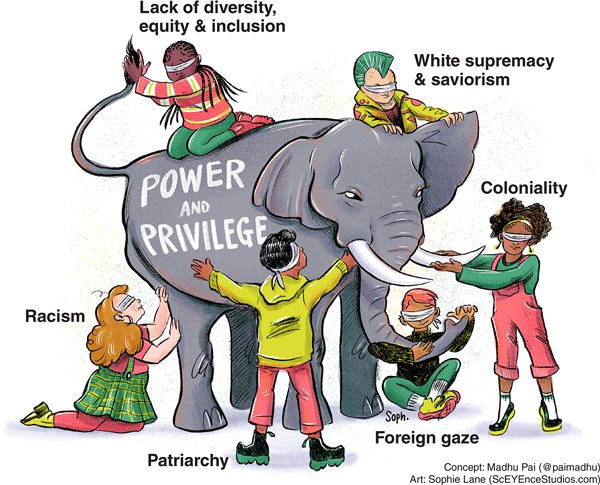

Factors such as lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion; White supremacy and saviorism1; colonialism, racism, and patriarchy; and the “foreign gaze”2 impact healthcare providers throughout the world. The shadow of colonialism3 continues to impact healthcare education, diversity, and equity.

1Saviorism: A policy that frames a group of people as needing to be saved, providing help in a self-serving manner. Often referred to as “White saviorism.”

2Foreign gaze: more than looking at a person—there is an implied imbalance of power or unequal power dynamic; the gazer is superior to and objectifying the object of the gaze. Also: male gaze, imperial gaze, medical gaze.

3Colonialism: the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.

At the individual level, there is a need to “decolonize” our minds from the colonial conditionings of our education. At the organizational level, global health organizations must practice real diversity and inclusion and localize their funding decisions. And at both the individual and organizational levels, there is a need to hold ourselves, our governments, and global health organizations accountable to these goals (Abimbola et al., 2021).

Global health has many asymmetries in power and privilege, including lack of diversity, white supremacy, racism, patriarchy, coloniality, and the foreign gaze. Image source: Madhukar Pai, with artwork by Sophie Lane. Reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Initiatives

Diversity is where everyone is invited to the party. Inclusion means that everyone gets to contribute to the playlist. Equity means that everyone has the opportunity to dance.

University of Michigan Chief Diversity Officer Robert Sellers

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives are offered to healthcare personnel in most healthcare organizations in the United States. These programs promote an appreciation and respect for differences and similarities in the workplace, including encouraging respect for the perspectives, approaches, and competencies of coworkers and clients. Inclusion helps people feel valued for their unique qualities while promoting collaboration within a diverse group.

Michigan Initiatives

Source: National Cancer Institute.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion programs are springing up in just about every industry and company. The Michigan Diversity Council provides training in a variety of areas related to diversity and inclusion, including a diversity certification program. Its goal is to help organizations develop individual, team, and organizational strategies to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The Department of Civil Rights in Michigan (MDCR) provides resources and training solutions that focus on race, systemic advantages and disadvantages, and how these issues intersect or interact. MDCR encourages organizations to develop action plans that endorse equity and inclusion and implement equitable practices, policies, and procedures (MDCR, 2022).

Medicaid and Medicare as Inclusion Initiatives

Medicare and Medicaid were created to cover people who did not have health insurance. They have played an important role in addressing limited healthcare access for racial and ethnic minority populations. Medicare funding provided powerful financial leverage for the early and proactive efforts of the Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights to secure the racial integration of hospitals (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022).

These programs have encouraged physicians, hospitals, and other providers to serve underserved communities. The programs reflect however, the racial paradox of the safety net: It is a product of a structurally racist health system in which racial and ethnic minority groups were disproportionately excluded from employer-sponsored health insurance, yet it is also an important, if limited, tool for filling this gap (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022).

Medicaid remains the largest public health insurance provider in the U.S., with more than 80 million enrollees. The racial composition of Medicaid enrollees underscores its importance in addressing racial inequity in healthcare. Nationwide, 30% of nonelderly Medicaid beneficiaries are Latinx, 20% are Black, and nearly 10% are part of other minority racial or ethnic groups (Commonwealth Fund, 2022).

Because Medicaid is highly fragmented and decentralized—with the federal government, states, and even localities making decisions about how to fund, design, and administer it—there are numerous places where inequities can occur. For example, state programs vary in terms of:

- Benefits offered.

- Waivers required for work-reporting requirements.

- Provider payments.

- Outreach efforts.

- Program administration (Commonwealth Fund, 2022).

Each of these variations have implications for how benefits are distributed across racial groups and for how policies interact with preexisting social and economic disadvantages. Yet, policymakers make many of these decisions without clear consideration of the repercussions their choices have for racial inequity (Commonwealth Fund, 2022).

Currently, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are the primary sources of coverage for many children of color. Medicaid covers about 30% of Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander nonelderly adults, and more than 20% of Hispanic nonelderly adults, compared to 17% of their White counterparts (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

For children, Medicaid and CHIP cover:

- More than 50% of Hispanic, Black, and American Indian/Alaska Native children.

- Nearly half of Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander children.

- About 27% of White children (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

The Affordable Care Act

In 2014, the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid to adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level ($18,754 annually for an individual in 2022). Medicaid expansion has been linked to increased access to care, improvements in some health outcomes, and reductions in racial disparities in health coverage (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

As of February 2022, 12 states have not yet adopted Medicaid expansion. In these non-expansion states, more than 2 million people fall into a coverage gap, with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to qualify for marketplace subsidies (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

Nearly six in ten people in the coverage gap are people of color. Uninsured Black adults are more likely than their White counterparts to fall into the gap (15% vs. 8%) because most states that have not expanded Medicaid are in the South where a larger share of the Black population resides (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

The American Rescue Plan Act, enacted in March 2021, includes a temporary fiscal incentive to encourage states to take up the expansion. While no state has newly adopted expansion since ARPA was enacted, this incentive reignited discussion around expansion in a few state legislatures. Also, in some states, advocates are pursuing expansion via ballot initiatives (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

The Build Back Better Act would temporarily close the Medicaid coverage gap. It would make low-income people eligible for subsidized coverage under the Affordable Care Act in states that have not expanded Medicaid (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

A recent Los Angeles Times article reported that Medicaid (Medi-Cal) patients experience a lack of access through the University of California’s health systems. This despite nearly 33% of California residents being insured through Medi-Cal.

The main reason given by UC administrators is the failure of Medi-Cal reimbursements to cover the cost of treatments. The situation is worse for medical specialties such as neurology, orthopedics, and cardiology, which often do not accept Medi-Cal insurance (Wilkes and Schriger, 2022).

In Michigan, more than 985,000 people receive health insurance through the Healthy Michigan Plan. A sizeable proportion of beneficiaries are young (18-34 years of age), and most work in low wage or seasonal jobs that do not provide insurance (Michling, 2022).

Michigan entered the COVID-19 pandemic with an expanded Medicaid program and a smaller percentage of its residents uninsured compared to several other states. Michigan’s Medicaid expansion was well established and intertwined with other health insurance coverage options, creating a higher baseline coverage. Michigan’s relatively aged population (ranking eighth nationally for the number of Medicare beneficiaries) was likely more insulated from pandemic-related insurance or income loss (Michling, 2022).