Measles is one of the world’s oldest and most contagious viral diseases. It is the leading cause of infant and child mortality globally, though unvaccinated adults are also susceptible. The first medical reference to the illness is by the ninth century Persian alchemist, philosopher, and physician Abū Bakr Muhammad Zakariyyā al-Rāzī, who described measles in his Treatise on Smallpox and Measles. It may have been present as early as the sixth century BCE, making it the oldest human RNA virus genome to have been sequenced thus far (Goodson and Rota, 2022).

The Measles Virus

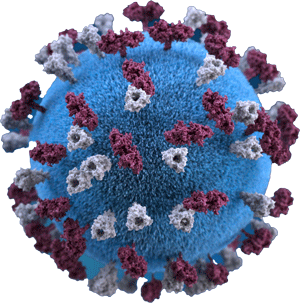

An illustration of the virus which causes measles. Source: CDC/ Allison M. Maiuri, MPH, CHES. Public domain.

Rubeola, commonly known as measles, is caused by the MeV measles virus, part of the Morbillivirus genus within the Paramyxoviridae family. It is distinct from the less dangerous rubella virus, which is commonly referred to as “German measles.”

True measles has an extremely high reproduction rate (Ro), meaning that one infected person can infect 12-18 other people within the course of normal social interactions. Airborne transmission is so effective that infectious particles in the tiny droplets of moisture in a sick person’s exhalations can linger and remain contagious for up to two hours. Initial symptoms, appearing 10–12 days after infection, include high fever, a runny nose, bloodshot eyes, and tiny white spots inside the mouth (Branda et al., 2024).

Many modern doctors in the United States have never (or rarely) seen a measles rash, which usually begins as flat red spots, sometimes with raised bumps, at the hairline around the face before moving down the body. The spots may merge as the rash spreads, with a fever of up to 104 degrees.

Measles Rash

Child with measles rash. Source: National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases; Division of Viral Diseases.

Measles has no cure and few treatment options beyond hydration to replace fluids lost by diarrhea or vomiting. Though measles is a virus, patients may develop bacterial pneumonia or ear and eye infections, which often require antibiotics. Good overall health and access to quality healthcare improves the chances of survival. Healthy people are not less susceptible to measles than people with comorbidities.

Most patients who die from measles succumb to pneumonia or severe dehydration. Even those who recover from a childhood bout with the virus are at risk of long-term effects, including hearing loss and permanent vision impairment or blindness. Some patients develop acute encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain, which can lead to lifelong brain damage. One late-onset complication is subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Though rare, SSPE is a fatal degenerative central nervous system condition that can appear more than a decade after the patient has apparently recovered from the initial infection.

Patients who survive emerge with a measles-specific immunity, but the virus has a unique feature called immune amnesia, which means that it resets the patient’s immune system so the cells are no longer immune to any other disease. In effect, a measles survivor must re-develop a whole new set of immunities. Measles-induced immune amnesia can last two to three years (Hagen, 2024).

Vaccination is the only way to prevent measles.