Nurse Jennifer was struggling to keep up while working a busy shift on her med-surg unit. A colleague had called in sick and the remaining nurses had to split his assignment of patients, with the result that Jennifer’s patient ratio increased by one. Then one patient in isolation took a downward trend and needed a blood transfusion; another patient needed to be started on Lovenox injections as they tapered him off his heparin drip; another was returning from surgery and put on total parenteral nutrition (TPN), requiring blood glucose monitoring every 4 hours.

In addition to these patients, she had to admit a patient in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with a nonhealing foot wound that required laboratory tests. Another patient was in respiratory distress with worsening COPD and concomitant Hepatitis C, and needed lab work. Each one of these patients would require interventions with needles.

Which patient would be the greatest risk of bloodborne pathogens? Is it the obvious patient—or someone else?

In the rush to obtain a laboratory specimen from the DKA patient, Jennifer accidentally stuck herself with the needle after the withdraw from the vein of her patient. Is Jennifer at risk? What is she supposed to do now? Who would she report to, if at all?

If you were Jennifer, what would you do? Do you know the risk factors, possible pathogens, process for reporting, and responsibility of her employer and herself? For healthcare workers, not becoming a “host to the pathogen party,” means being prepared, knowledgeable and proactive.

You came to the right place to find out.

Defining the Danger

Transmission Ports for Bloodborne Pathogens

Source: Google Images.

Bloodborne pathogens are infectious organisms in blood and other body fluids that can cause chronic and life-threatening disease in humans. The main bloodborne pathogens of concern are hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the organism that causes AIDS. Transmission of any of these can be through open sores, cuts, abrasions, damaged skin, or mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, mouth, vagina or anus.

For healthcare workers, hepatitis B and C are the most common and contagious in the medical settings.

The Science

Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B

There are five main types of hepatitis, and all create inflammation and damage to the liver. Clinical symptoms can be puzzling because they may be absent, mild to severe, acute, or chronic. The types of hepatitis are:

- Hepatitis A (HAV): spread through the anus via feces. Think A for anus.

- Hepatitis B (HBV): spread through blood and body fluids. Think B for blood.

- Hepatitis C (HCV): spread through body fluid contact. Think C for contact fluids.

- Hepatitis D (HDV): a variation if you already have HBV. The HBV vaccine protects against HDV. Think “Double Trouble” from HBV.

- Hepatitis E (HEV): transmitted via food or water. A vaccine exists but not globally available yet. Think E for environmental.

Recent reports of viral hepatitis A (HAV) and B (HBV) outbreaks in the United States demonstrate the continued risk posed by lapses in infection-control practices, particularly in healthcare settings (Dan, 2017). Each week the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) receive electronic reports from all 50 states about viral hepatitis cases in their states (CDC, 2019). Because many people infected with viral hepatitis are asymptomatic, many cases are not reported, which means current statistics are actually underestimated (CDC, 2016).

Source: Google Images.

HAV is a virus that is transmitted generally from fecal matter into food or water and HBV is transmitted by percutaneous or mucosal exposure to the blood or body fluids of an infected person. It is known to survive in dried blood for up to 7 days. Most often HBV is transmitted through injection-drug use, from sexual contact with an infected person, or from an infected mother to her newborn during childbirth. Transmission of HBV also can occur among people such as healthcare workers who have prolonged but nonsexual interpersonal contact with someone who is HBV-infected (CDC, 2016).

Infection may be acute—and later resolved—or it may become chronic, carried for a prolonged period, or for life. Infection may be completely free of symptoms, produce mild or moderate illness, or be rapidly fatal. Serious complications such as cirrhosis and/or liver cancer are more likely to develop in chronically infected people.

Incidence and Prevalence

In the United States, approximately 2.2 million people have chronic HBV infection and become sources for HBV transmission to others. Because of the mandatory HBV vaccine initiated in 2006, the incidence of acute hepatitis B among native-born children has declined steadily (CDC, 2016).

Unfortunately, the incidence of HBV in the adult population in the United States has been climbing, and the largest population at risk occurs in immigrant and non-native-born people. Three quarters of chronic HBV infections are among people born outside of the United States, 58% of whom are from Asian countries (Kowdley et al., 2012).

Risk factors for HAV include behaviors such as people:

- Who work with food and do not thoroughly wash their hands after a bowel movement and then carry infected fecal material on their hands during food preparation.

Risk factors for HBV include behaviors such as people:

- Who share contaminated needles

- Who have received contaminated blood products (since new screening procedures were implemented in 1992, this is a rare occurrence in the United States)

- Who get body piercings or tattoos with instruments that have not been properly sterilized

- Who work in healthcare and may be stuck accidentally with contaminated needles

- Are living with HIV

- Are newborns whose mothers are HCV-positive

Symptoms, which mainly represent liver damage, can include:

- Yellowing skin and eyes (jaundice)

- Dark urine

- Light-colored stool

- Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and discomfort

- Loss of appetite

- Extreme fatigue

- Flu-like symptoms

Diagnostic criteria include:

- Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 100 IU/L

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive, or nucleic acid test for HBV DNA

- Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc) positive

- HBeAg positive 2 times tested 6 months apart

Treatment of HBV includes palliative care for the resultant nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Since publication of the 2008 recommendations, treatment options for HBV infection have expanded. Several drugs are now administered orally, which is a major advancement for this infection. This leads to viral suppression in 90% of patients taking one of these new oral medications. There is currently no cure but the HBV direct-acting antivirals available are interferon, peginterferon, and ribavirin (AASLD, 2019).

Effective hepatitis B vaccines have been available in the United States since 1981. In addition to hepatitis B vaccination, efforts have been made to improve care and treatment for people living with hepatitis B. In the United States, as many as 2.2 million people are estimated to be infected with HBV, most of whom are unaware of their infection status, and 3.5 million are infected with HCV (CDC, 2016).

To improve health outcomes for these people, CDC issued recommendations in 2008 to guide hepatitis B testing and public health management of people with chronic hepatitis B infection. These guidelines stress the need for testing people at high risk, conducting contact management, educating patients, and administering FDA-approved therapies for treating hepatitis B (CDC, 2008).

The risk of transmission of HBV following a positive needle stick varies from 6% to 30%, depending on the degree of infectivity of the source individual. Healthcare workers who have received hepatitis B vaccine and have developed immunity to the virus are at minimal risk for infection.

For an unvaccinated person, the risk from a single needle stick or a cut exposure to HBV-infected blood ranges from 6% to 30% and depends on the hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) status of the source individual. Individuals who are both hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive and HBeAg-positive have more virus in their blood and are more likely to transmit HBV (CDC, 2016).

Hepatitis C

[Unless otherwise noted, most of the material on Hepatitis C in this section is from Hofmeister et al., 2018.]

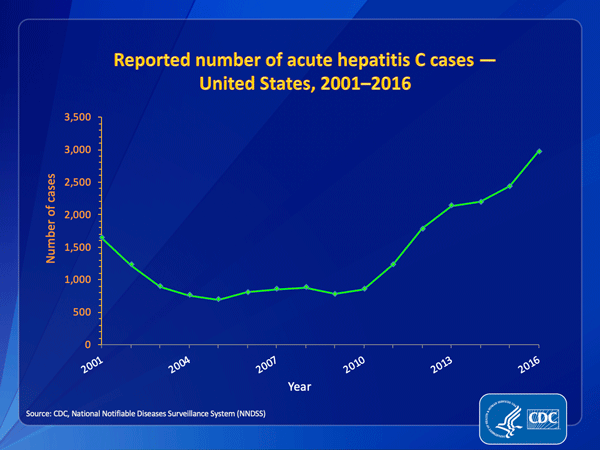

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted primarily through percutaneous exposure, most commonly by injection-drug use. It causes damage to the liver. Currently, there is no vaccine for hepatitis C. The best way to prevent hepatitis C is by avoiding behaviors that can spread the disease, notably the use of injecting drugs. People newly infected with HCV are usually asymptomatic, so the acute phase is rarely identified or reported. With an estimated 3.5 million chronically infected people nationwide, HCV infection is the most common bloodborne infection in the United States (Healthline, 2019; CDC, 2016).

Source: CDC, 2016.

Incidence and Prevalence

Chronic hepatitis C is a serious disease than can result in long-term health problems, even death. For some people, hepatitis C is a short-term illness, but for 70 % to 85% of people infected, it becomes chronic. Conversely, about 15% to 25% of people clear the virus from their bodies without treatment; the reasons for this are not well known. The majority of infected individuals may not be aware of their infection because they are not clinically ill.

Chronic HCV infection is the leading indication for liver transplants in the United States. Most people with chronic HCV infection are asymptomatic; however, many have chronic liver disease, which can range from mild to severe, including cirrhosis and liver cancer. Chronic liver disease in HCV-infected people is usually insidious, progressing slowly without any signs or symptoms for several decades.

Based on limited studies, the estimated risk for infection after a needle stick or open wound exposure to HCV-infected blood is approximately 1.8%, or 1 in 50 (CDC, 2016). The risk following a blood splash to mucous membranes is unknown but is believed to be very small; however, HCV infection from such an exposure has been reported.

There is no vaccine or post exposure prophylaxis against HCV, although research is under way. Prevention of exposure is the only protection against infection. New treatments are being offered; see below.

According to the World Health Organization, HCV can improve without treatment within six months in up to 45% of cases, however 55% will develop chronic HCV infection and liver damage. Compared to the 3 million in the United States currently diagnosed with chronic HCV, an estimated 71 million people worldwide are living with chronic HCV and up to 500,000 die annually from HCV-related complications (Healthline, 2019).

Risk factors include behaviors such as those of people who:

- Share contaminated needles

- Have received contaminated blood products (since new screening procedures were implemented in 1992, this is a rare occurrence in the united states)

- Get body piercings or tattoos with instruments that have not been properly sterilized

- Work in healthcare and may be accidentally stuck with contaminated needles

- Are living with HIV

- Are newborns whose mothers are HCV-positive

Symptoms, which mainly represent liver damage, can include:

- Yellowing skin and eyes (jaundice)

- Dark urine

- Light-colored stool

- Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and discomfort

- Loss of appetite

- Extreme fatigue

Diagnostic criteria include:

- Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 100 IU/L

- Hepatitis C surface antigen (HCsAg) positive, or nucleic acid test for HCV DNA

- Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to hepatitis C core antigen (IgM anti-HCc) positive

- HCeAg positive 2 times tested 6 months apart

Treatment for Acute Hepatitis C

New treatment guidelines recommend no treatment of acute hepatitis C. Patients with acute HCV infection should be followed and only considered for treatment if HCV RNA persists after 6 months.

Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis C

The treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has evolved substantially since the introduction of highly effective HCV protease inhibitor therapies in 2011. Since that time, new drugs with different mechanisms of action have become, and continue to become, available.

Currently available therapies can achieve sustained virologic response (SVR) defined as the absence of detectable virus 12 weeks after completion of treatment; an SVR is indicative of a cure of HCV infection. Over 90% of HCV-infected individuals can be cured of HCV infection regardless of HCV genotype, with 8 to 12 weeks of oral therapy.

HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the virus that causes AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), which was first identified in 1981. For an infected individual, many years may pass between the time of infection and symptoms of illness begin or are identified. Individuals who have the virus but are not yet sick have no symptoms and many do not know they are infected. Medications can slow the course of the disease, and there are medications that can be taken after exposure to reduce the likelihood of post exposure infection (PEP).

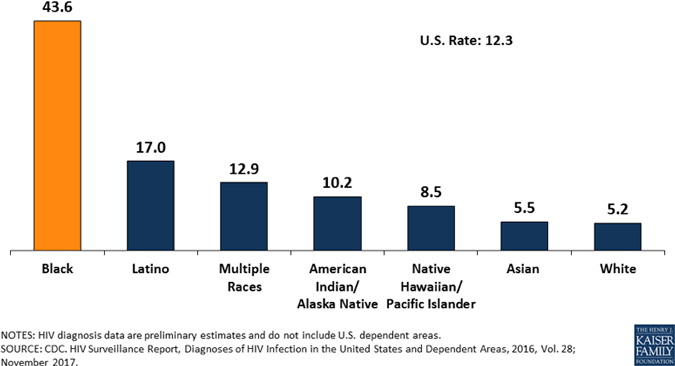

Rates of New HIV Diagnoses per 100,000 by Race/Ethnicity, 2016

Source: CDC, 2017.

Incidence and Prevalence

The average risk for HIV infection after a needle stick or laceration exposure to HlV-infected blood is 0.3% (about 1 in 300). Statistically, 99.7% of needle stick/cut exposures to HIV-contaminated blood do not lead to infection. The risk after exposure of the eye, nose, or mouth to HIV-infected blood is estimated to average 1 in 1000 (CDC, 2016). These are encouraging statistics—unless you are the one. The risk is low, but it is not zero.

Risk factors for HIV include the same ones as for HAV, HBV, and HCV, and include those:

- Homosexual sexual activities of anal/oral intercourse with someone infected

- Heterosexual sexual activities of anal/oral intercourse with someone infected

- Who share contaminated needles

- Who have received contaminated blood products (since new screening procedures were implemented in 1992, this is a rare occurrence in the United States)

- Who get body piercings or tattoos with instruments that have not been properly sterilized

- Who work in healthcare and may be accidentally stuck with contaminated needles

- Newborns whose mothers are HIV-positive

Symptoms are similar to illnesses caused by other viral infections, and can include:

- Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and discomfort

- Loss of appetite

- Extreme fatigue

- Weight loss

- Frequent fever and sweats

- Lymph node enlargement

- Yeast infections, skin irritations and rashes and/or flaky and itchy skin

- diarrhea

Diagnostic criteria for HIV Positive diagnosis include:

- ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) test, which measures antibodies against HIV)

- Western Blot test: used to confirm positive ELISA test

- Saliva tests. A cotton pad is used to obtain saliva from the inside oral cheek. Must be later confirmed with blood test.

- Viral Load test. This test measures the amount of HIV in your blood.

- VDRL (venereal disease research laboratory) and rapid plasma regain (RPR)

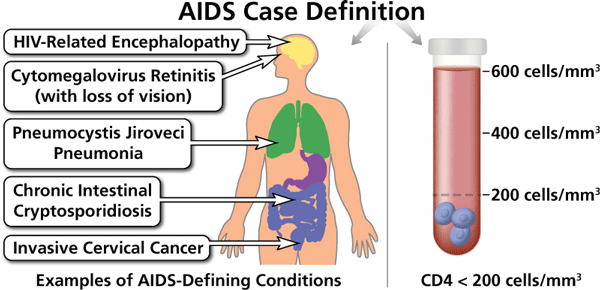

Diagnostic criteria for AIDS Positive diagnosis include:

- AIDS-defining condition with CD4 count less than 200 cell/mm3

Treatment of HIV/AIDS includes a cocktail of highly active anti-retroviral medications (HAART) and education and prevention strategies for opportunistic infections (Cash & Glass, 2017). There is no-known cure for HIV/AIDS and it is therefore a fatal disease.

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019.

Who Is at Risk?

It is not at all rare for people to carry more than one of the three viruses just discussed, since these pathogens are spread by similar routes: blood-to-blood contact, sexual contact, and injecting-drug use. As many as 25% of people with HIV also have HCV and up to 10% of those with HCV also have HBV (Healthline, 2019). Having one infection does not mean an individual automatically has the others, but it is prudent clinical practice to screen for the others.

In addition to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV, other less-common bloodborne pathogens include:

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (caused by HTLV-I)

- Arboviral infections

- Babesiosis

- Brucellosis

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- Diseases associated with HTLV-II

- Hepatitis delta (HDV)

- HTLV-I–associated myelopathy

- Leptospirosis

- Malaria

- Relapsing fever

- Syphilis

- Viral hemorrhagic fever (OSHA, 2019a)

Some of the listed diseases are extremely rare in the United States; however, today’s mobility of individuals and families means that rare diseases can travel globally. Healthcare workers abroad need to be aware of the possible risk of exposure to rare diseases as well as those common to their own country. In this country, rates of HCV are higher among Asians and African Americans than other ethnicities (CDC, 2016).

The most important thing to remember about all four of the main viruses is that most people infected with them are asymptomatic. This is why it is critical to avoid contact with the blood and body fluids of all individuals, since there is no easy way to tell those infected from those who are not.

Those who are at risk or any of the bloodborne pathogens includes:

- People who have contact with blood or body fluids in their personal lives, whether through sexual activity, by injected drug use, or by other mechanisms

- Patients who may have exposure to the blood or body fluids of caregivers by unintended means

- People who have contact with blood or body fluids in their work-life (occupational exposure)

Chronic Infectious Diseases in the United States, 2016 | ||

|---|---|---|

Disease | People infected | Annual new infections |

HIV/AIDS | 1.1 million | 40,000 |

Hepatitis A | 0.02%/100,000 | 4,000 |

Hepatitis B | 2.2 million | 20, 900 |

Hepatitis C | 41,200 | 2,967 |

Test Your Knowledge

Bloodborne pathogens:

- Include lice and fleas that can be transmitted to another person by contact with contaminated bedding or clothes.

- May be spread through contact with the intact skin of an infected person.

- Are infectious materials in blood or body fluids that can cause disease in humans.

- Cannot be spread through cerebral spinal fluid because the blood-brain barrier prevents passage of organisms into the spinal fluid.

The most common bloodborne infection in the United States is:

- Malaria.

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

- HCV infection.

- Syphilis.

About the three main bloodborne viruses—HBV, HCV, and HIV—the most important thing to remember is that:

- Most people infected with them are asymptomatic.

- People who have one will not be co-infected with one of the others.

- Laboratory tests can always return accurate results within 24 hours.

- Healthcare personnel develop a natural immunity that protects them from becoming infected with one of the bloodborne viruses.

Apply Your Knowledge

As a healthcare worker, what are the clinical symptoms you would look for in someone who has a hepatitis virus? How are the clinical symptoms different from HIV/AIDS?

Answers: C,C,A

The Law

OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard

Law regarding bloodborne pathogens is based on the federal OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, 29 CFR 1910.1030, originally passed into law in 1992 and updated as needed. All the requirements of the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard are designed to protect workers from exposure to bloodborne pathogens or other potentially infectious material (OPIM), (OSHA, 2019b).

The standard requires employers to do the following:

- Establish an exposure control plan.

- Update the plan annually.

- Implement the use of universal precautions.

- Identify and use engineering controls.

- Identify and ensure the use of work practice controls.

- Provide PPE for employees.

- Make available hepatitis B vaccinations to all workers with occupational exposure.

- Make available post-exposure evaluation and follow-up.

- Use labels and signs to communicate hazards.

- Provide information and training to workers.

- Maintain worker medical and training records.

State Laws

State legislation has been enacted in twenty-two states to improve healthcare worker safety related to needle sticks. These laws add provisions not included in the federal OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen standard and/or coverage of public employees not regulated by OSHA. These laws contain unique requirements such as surveillance programs, cost-benefit analyses, strict requirements for safety device use, and the use of statewide advisory boards.

Implementation of state laws differs regarding development of related regulations and the dates when they become effective. State-by-state provisions are available online (OSHA, 2019a). Resources for state laws are listed at the end of this course.

Compliance with the federal law and any applicable state law is required of all workplace settings where healthcare workers may be exposed to blood or body fluids on the job, including hospitals, clinics, surgical centers, research facilities, and anywhere they may be exposed to human tissue and blood products.

Test Your Knowledge

OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard:

- Was originally passed into law in 1980.

- Has not been amended since 2001.

- Is amended biannually by OSHA.

- Has been amended every five years.

Apply Your Knowledge

What are your employer’s annual education requirements regarding bloodborne pathogens? When did you last complete the required training? Do you have a personal copy of your compliance with the annual training?

Answer: B