Screening is one part of the story. When people screen positive for suicide risk, it’s important to follow that with a full assessment and evidence-based approaches for intervention and follow-up care.

Stephen O’Connor, Ph.D.

Chief of the NIMH Suicide Prevention Research Program

Mental health has traditionally been within the purview of psychiatrists and specifically trained mental health practitioners. But over the last 2-3 decades, family practice physicians, nurse practitioners, allied health professionals, dentists, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers have become increasingly responsible for identifying and managing chronic mental health problems—including suicidal ideation and behaviors.

Now, a wide range of healthcare providers find themselves at the front lines of identifying serious mental health issues that require screening, assessment, and referral. Because of these changes, all healthcare providers need to be knowledgeable about suicide risk factors and warning signs, and suicide screening and assessment tools. Following a screen, they must know when, where, and how to refer a client who is at risk for self-harm. Screening can be the start of successful suicide prevention efforts.

Existing research shows that many individuals who die by suicide consult health services prior to their death: 9% on the day of death, 34% during the week prior, and 61% in the month before their death. Emergency department visits are particularly prevalent among suicide decedents (Scudder et al., 2022). These statistics highlight the importance of screening, assessment, and referrals, not just in emergency departments but in all healthcare setting.

Did You Know. . .

Fifty-eight percent of military service members who died by suicide in 2016 had contact with the healthcare delivery system in the 90 days prior to their death; roughly a third of those encounters were with outpatient or inpatient behavioral health (VA/DOD, 2019).

In 2022, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) stated with moderate certainty that screening for major depressive disorder in adults (including pregnant and postpartum persons and older adults), has a moderate net benefit. They reiterated their 2014 recommendations however, that the evidence is insufficient on the benefit and harms of screening for suicide risk in adults. In the absence of compelling evidence, the USPSTF nevertheless encourages healthcare professionals to use their judgment—based on individual patient circumstances—when determining whether to screen for suicide risk in adults not showing signs or symptoms (USPSTF, 2022).

Despite the USPSTF recommendations, many professional organizations are moving forward with practice guidelines that encourage or require screening for suicidal ideation and behaviors. In 2022, the American Association of Pediatrics published screening recommendations for youth and young adults that state (AAP, 2024):

- Youth ages 12+: Universal screening.

- Youth ages 8-11: Screen when clinically indicated.

- Youth under age 8: Screening not indicated. Assess for suicidal thoughts/behaviors if warning signs are present.

Zero Suicide is another organization that is advocating for universal suicide risk screening in all healthcare organizations. Growing support for the model has led to the implementation of projects across diverse healthcare systems, states, and tribal nations. The goal is to prevent all patient suicides and to provide a framework for suicide prevention within healthcare settings (Layman et al., 2021).

In a Zero Suicide approach (Zero Suicide, 2022):

- All individuals are screened for suicide risk at their first contact with the organization and at every subsequent contact.

- All staff members use the same tool and procedures to ensure that individuals at risk of suicide are identified.

- Clinicians conduct a thorough suicide risk assessment when an individual screens positive for suicide risk.

- All staff members use a standardized tool and procedure to gather information to fully assess an individual’s suicide risk and create a plan to address that risk.

Within military organizations, universal screening for suicide risk is reportedly controversial and has received mixed support. Nevertheless, the Veteran’s Administration has identified screening as a key part of their Community-Based Intervention for Suicide Prevention program. The program has 3 components (USDVA, 2021, September):

- Identifying service members, veterans, and their families and screening for suicide risk.

- Promoting connectedness and improving care transitions.

- Increasing lethal means safety and safety planning.

3.1 How and When to Screen

It’s not realistic to expect healthcare providers to be able to figure out who they should screen and who they shouldn’t. When screening is universal, it becomes standardized, and it sets the expectation that every patient will be screened.

Stephen O’Connor, Ph.D.

Chief of the NIMH Suicide Prevention Research Program

Suicide prevention starts with a screen, which allows a screener to identify and intervene before a person acts on their desire to die. Screening provides an opportunity for a person at risk to share their feelings of despair and allows the person doing the screening to discuss alternatives to suicide.

By definition, screening is an informal process. It compares the before to the now by asking questions, determining risk factors, and if needed, referring the person to someone who can screen and assess at a higher level, usually a mental health professional.

Screening can be completed by anyone in the community, including peer support and employee support personnel, gatekeepers, crisis line volunteers, family and friends, teachers, clergy, law enforcement personnel, firefighters, and non-mental health medical providers and workers. Although screening can be done by anyone, it is vital that anyone doing a suicide screen be aware of the absolute need to refer a high-risk person to a higher level of care.

A suicide screen uses a standardized instrument or protocol to identify individuals who may be at risk for suicide. Suicide screening can be done independently or as part of a more comprehensive health or behavioral health screening. Screening may be done orally (with the screener asking questions), with pencil and paper, or using a computer (SPRC, 2014).

On the surface, asking every patient who receives care in a medical setting to complete a suicide risk screening may seem unnecessary or excessive. But research shows that this approach, known as universal screening, identifies many people at risk who might otherwise be missed (NIMH, 2023).

Healthcare providers and workers should become familiar with a simple screening tool and, importantly, practice the screening questions until they are comfortable leading a client through a screen. If a screen indicates increased risk, be prepared to make an immediate referral, making sure your client transitions safely from your office or clinic to the point of actual service. The overreaching goal is not to diagnose, but to be ready to talk, keep the person safe, and have referral information readily available.

Something as simple as a waiting room questionnaire or a quick, two-question screening tool can identify high-risk individuals who otherwise may not be identified. A brief screening tool may be able to identify individuals at risk for suicide more reliably than leaving the identification up to a provider’s personal judgment or by asking about suicidal thoughts using vague or softened language.

For those working in outpatient clinics, social services, counseling services, employee support services, dental offices, or community pharmacies, clients should be screened regularly, preferably at each visit. For many of these individuals, the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts is higher than the general population.

For screening to be effective, healthcare providers must:

- Be knowledgeable about suicide warning signs.

- Learn about risk and protective factors.

- Practice questions ahead of time.

- Understand how your own attitudes and beliefs impact your clients.

3.1.1 Structuring the Interview

Asking someone about suicide will feel like vinegar on your tongue at first but with practice, it gets easier. Learn to acknowledge the person, not the condition. Questions such as, “Have you had a problem like this in the past?” or, “What have you done in the past that has worked for you?” build a rapport with the person you are interviewing.

Dr. Naomi Paget

Fellow, American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress

Screening for suicide risk requires a thoughtful, caring, and non-judgmental approach. Because asking about suicide is not easy, it is essential to practice interview skills at home or with a co-worker—and on a regular basis. Develop and practice questions until you are comfortable leading a patient through a screen. Asking a difficult question does not plant the idea of suicide.

Most healthcare providers are trained in how to assess or evaluate a patient—life history, previous suicide attempts, and a person’s current mental state. But assessment is different than screening, especially for non-mental health providers. Unfortunately, little attention has been paid to how to interview or screen patients who are thinking about, considering, or planning suicide. This is important because the way questions are asked—the words and phrasing used by a clinician—can influence a person’s response (McCabe et al., 2017).

3.1.2 Asking About Safety, Lethality, and Intent

As part of the screening process, the screener must decide what direction the potential self-harm is heading—from superficial and visible self-harm to deeper and less visible self-injury. People with certain types of mental illness are more likely to be associated with escalating self-harm, with an ever-greater likelihood of a completed suicide.

Safety, lethality, and intent are important aspects of an initial screen. Asking about safety starts with a general, open-ended question. Keep in mind that a person who is depressed may have trouble organizing their thoughts and their responses may be delayed. Be patient and give time for an answer. Develop a series of questions that help you determine the level of care needed for patient safety to be preserved.

If the person refuses to answer or if there is a long pause, ask a direct question such as, “Has something happened recently that has affected your well-being?” The person might respond by saying, for example, “My mother just died—she was my whole life.” You can then ask, “Now that your mother has died, what else in your life will bring you joy?” This might be followed by a question of concern such as: “I wonder—has the thought of hurting yourself entered your mind?”

Although yes/no questions are common in healthcare interactions, they can communicate an expectation in favor of either a yes or no response. For example, “Are you feeling low?” invites agreement to “feeling low.” Conversely, “Not feeling low?” invites agreement to “not feeling low.” Specific positive or negative words can reinforce bias. Words such as “any,” “ever,” or “at all” reinforce negative bias (e.g., “Any negative thoughts?”) while words such as “some” reinforce positive bias (e.g., “Do you have some pain here?”) (McCabe et al., 2017).

If a patient indicates an immediate (imminent) intention to harm themself, your next act is to refer the patient to someone who is licensed to decide about an involuntary hold. In larger organizations, psychiatric services are often directly available. Depending on the level of risk, patients can be held against their wishes. If a person agrees to hospitalization, they must be placed in the least restrictive environment. Determining whether a patient is safe (and whether they can be held against their will) is left to providers who are legally licensed to make that determination.

The next step is to ask about lethality. Nonsuicidal self-injury often involves people with borderline personality disorders and self-harm can be an antidote to psychological numbing. Lethality focuses on the method used, the circumstances surrounding the attempt, and the chance of rescue. Lethality is related to the severity of physical consequences as well as the amount of medical intervention needed following an attempt (Kar et al., 2014).

Five Levels of Lethality

The lethality of suicidal behavior can be considered to have five levels: subliminal, low, moderate, high, and extremely high (Kar et al., 2014).

- Subliminal. Death is impossible to highly improbable.

- Low. Death is improbable and is not the usual outcome but may be possible as a secondary complication of factors other than the suicidal behavior.

- Moderate. Probability of death is in the middle order.

- High. Chance of death is high and is the usual or likely outcome of the suicidal act.

- Extremely high. Chance of survival is minimal, and death is considered almost certain.

When asking about lethality, try to determine how well thought out the plan is and whether the person has access to the means to complete the plan. Note any additional circumstances and try to evaluate the “risk tipping point.” Determine if it is necessary to take an action that deprives a patient of his or her rights vs. not taking an action that might result in suicide.

There is often a mismatch between the lethality of the method chosen and the intent of the suicidal act. People who genuinely want to die (and expect to die) may survive because the chosen method was not foolproof or because they were interrupted or rescued. However potentially lethal the chosen method is, a prior suicide attempt is a highly potent risk factor for eventually dying by suicide. All suicide attempts must be taken seriously, including those that involve little risk of death, and any suicidal thoughts must be carefully considered in relation to the client’s history and current presentation (CSAT, 2017).

Determining a person’s intent to die during a screen is an important indicator of current and future risk. Intention reflects how hard a person is willing to try or the likelihood a person will perform—or try to perform—a particular behavior (Williams, 2015). Patients who have a clear intention of taking their life require higher levels of protection than those with less inclination toward dying.

A person’s intent may be inferred from how they describe a “wish to live” or a “wish to die.” These terms have proven useful in assessing suicide ideation and behavior and are included in Beck’s Scale of Suicidal Ideation and the Suicide Status form. Overall, there is strong evidence that suicidal affect can be a valid indicator of current and future risk (Harris et al., 2015).

Beck Suicide Intention Scale

The Beck Suicide Intention Scale (SIS) examines subjective and objective aspects of the suicide attempt, the circumstances at the time of the attempt, and the patient’s thoughts and feelings during the attempt. It is based on a clinical interview using an instrument with 15 items referring to the patient’s precautions and beliefs of the act. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 2, with a possible total score of 30 indicating the highest intention of suicide and a wish to die.

The Beck SIS questionnaire covers precautions, planning, communication, and expectations regarding medication load, the degree of planning, and wish to die or live. It is divided into two sections: the first eight items constitute the “circumstances” (part 1) and are concerned with the objective circumstances of the act of self-harm; the remaining seven items, the “self-report” (part 2), are based on the patients’ own reconstruction of their feelings and thoughts at the time of the act.

Source: Grimholt et al., 2017

Case: Valeria Cuts Her Wrists (Again)

Background

Serena is a physical therapist working in a small, rural outpatient rehab clinic in northern Washington. She recently had a client referred for evaluation and treatment of low back pain. When Valeria walked in from the waiting room, Serena noticed she was hunched over a little, her head was down, she walked slowly, and she had bandages on both wrists.

Before beginning the physical examination, Serena asked if Valeria ever thought about harming herself. Valeria’s direct and frank response startled Serena. With her eyes downcast and in a timid voice, Valeria said that, yes, she had hurt herself in the past and often thought about suicide. She nervously related, “The first time I tried to hurt myself, I took a bottle of aspirin. The second time I was 17 and I slit my wrists, but I screamed when I saw the blood.”

Serena asked her if anything had happened recently that had affected her well-being or mood. Valeria tearfully said, “Last week my boyfriend broke up with me and it really upset me. Two days ago, I drank 2 bottles of whiskey and slit my wrists in the bathtub. When I saw the blood in the water I got scared and jumped out of the tub and drained the water. I taped my wrists, but I didn’t tell anyone what had happened.” She asked Serena why she was asking her about suicide when she was at the clinic for back pain.

What do you think stands out in Valeria’s description of her suicide attempts?

- She is very calm and articulate.

- She seems upset but not depressed.

- Her suicide attempts have become more sophisticated.

- She doesn’t seem to really want to harm herself.

Answer: C

Screening for Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors

Serena noted that Valeria had succeeded in harming herself more than once and that her attempts have accelerated. This increased her concern for Valeria’s safety because the more times a person attempts suicide, the more likely they are to complete the event. It is her clinic’s policy to screen all clients for suicidal ideation and behaviors using the Patient Health Questionnaire 2, so Serena asked Valerie: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?”

[Answers are given as 0 to 3, using this scale: 0 = Not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; 3 = nearly every day.]

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things

- Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless

Valeria indicated she has these feelings every day (3) on both screening questions.

What Should Serena do?

Serena’s outpatient physical therapy clinic has no mental health services, but her clinic has a policy that anyone who marks a 2 or 3 on either PHQ2 screening question should receive a more thorough assessment and be referred to a mental health specialist. Serena’s supervisor tells her to either use the PHQ9 for a more in-depth assessment or refer her patient to the local emergency department for assessment by a mental health professional. Because Serena is not a mental health professional and has not been trained on the PHQ9, she decides to refer Valeria to the local emergency department.

Valeria tells Serena that she has no family living nearby. Serena feels Valeria is a danger to herself, so she decides to call the police to transport Valeria to the emergency department. She also provides Valeria with the phone number for a suicide hotline. Serena followed up with a call the ER and learns that Valeria arrived safely at the hospital.

Bottom Line

Because previous suicide attempts are known to be a strong predictor of future attempts and deaths by suicide, continuity of care is critical. For Valeria, who has survived a suicide attempt, effective clinical care should focus on alternatives to suicide, community and family support, therapy, and lethal means restriction.

3.1.3 Talking About Lethal Means

Talking about lethal means is critically important because certain lethal means such as firearms, hanging/suffocation, or jumping from heights provide little opportunity for rescue and have high fatality rates. Lethal means safety, including firearm restrictions, reducing access to poisons and medications associated with overdose, and barriers to jumping from lethal heights, have been shown to reduce population-level suicide rates (VA, DOD, 2019).

If you have identified that your patient is at risk for self-harm during a screen, ask them to identify any lethal means they might be able to access once they leave your office. You are more likely to elicit accurate information by asking permission and showing concern in a non-judgmental manner. Try to establish rapport and trust—if you think the person is at risk, there is no reason to cover your concern or to lie.

You can say, “I want to let you know that I appreciate and am honored that you’ve shared your thoughts with me. I’m just concerned that you may go again to a place of despair when you leave and I’m thinking of your safety.” Involving family, friends, and caregivers can be helpful. You can ask, “While you’re in this dangerous period, may I call your partner or family member and ask them to remove any guns or poisons from the house?”

Despite the importance of discussing lethal means, a study of 800 emergency department charts of patients who screened positive for suicidal ideation and suicide risk revealed that only 18% had any documentation of an assessment of lethal means. For the small group who were asked about lethal means, only 8% had documentation that a safety/action plan to reduce access to lethal means was discussed. The most common discussion involved addressing home storage of dangerous items or moving objects out of the home (Harmer et al., 2022).

Findings from the ED study show the need to document lethal means assessments for all individuals who have a positive screen for suicidal ideation, including a discussion about removal of lethal means. This may require adding prompts for these assessments to the electronic documentation system (Harmer et al., 2022).

A program developed at a large children’s hospital called the Emergency Department Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (ED CALM) trained psychiatric emergency clinicians to provide lethal means counseling and safe storage boxes to parents of patients under age 18 receiving care for suicidal behavior. In a pre/post quality improvement project, researchers found that, at posttest, 76% reported that all medications in the home were locked up as compared to fewer than 10% at the time of the initial ED visit. Among parents who indicated the presence of guns in the home at pretest (67%), all (100%) reported guns were currently locked up at posttest (Stone et al., 2022).

Case: Kathleen

In the two-and-a-half years since my son’s death I have learned that his story is, sadly, not uncommon. I have become oddly close with other mystified parents of seemingly successful, engaged, social young men and women who took their lives. They are my partners in grief, and in understanding why suicide is the number two killer of youth in Washington State, just behind accidents.

My son retrieved a gun that was unlocked because it had not been fired in many years and we didn’t think there was any ammunition in the house. Although we have learned that he was showing some warning signs, I will never know what he was thinking, because that gun left him with no chance of survival.

My son was a trained marksman who had attended gun camp every summer. He had also taken the hunter safety class, and was, as his hunting mentor said, “safer with a gun than any adult I know.” I have great respect for the people who trained my son, but not once did any of the safety materials include warnings for parents of youth that 79% of firearm deaths in Washington State are suicides. I had not dreamed that my son was suicidal, much less that he would consider using a gun to take his life. I sincerely hope that other parents safely store firearms and ammunition out of the reach of children.

Kathleen Gilligan, whose son Palmerston Burk died from suicide by firearm in King County in 2012. Source: WSDOH, 2016.

3.1.4 When Harm Is Imminent

The potential for imminent (immediate) self-harm exists when someone feels they are a burden, when there is no longer a sense of belonging, and when there is a history of self-injury. The risk of imminent harm is elevated during the days and weeks following hospitalization, especially for people diagnosed with major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. If a screen indicates that a patient is at immediate risk of self-harm, be ready to talk, keep the person safe, and have referral information readily available. The goal is to keep the patient safe until help arrives.

3.2 Screening Tools

Did You Know. . .

Beginning July 1, 2019, healthcare professionals are required by the Joint Commission to use a validated tool to assess suicidal risk for all patients whose primary reason for seeking healthcare is the treatment or evaluation of a behavioral health condition.

Harmer et al., 2022

Although there is some disagreement about the effectiveness of screening for suicide, improved identification of suicide risk is recommended by the Surgeon General’s office, advocacy organizations, and accreditation bodies and use of standard depression questionnaires for screening and assessing treatment outcomes is now widespread (Simon et al., 2023). A positive screen should always be followed by an in-depth assessment or an immediate referral to someone with the training and skills to conduct an in-depth assessment.

Screeners should be aware that screening can yield unacceptably high false-positive prediction rates. Many people determined to be “at risk” never experience clinically significant suicidal thoughts or behaviors and a substantial portion of individuals who die by suicide were not identified by the screening tools (VA/DOD, 2019).

What follows is a sampling of some of the most commonly used screens for suicidal ideation and suicide risk.

3.2.1 Patient Health Questionnaire 2

The Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ2) is a widely used, validated screening tool. It is used by many large hospital organizations, including Washington’s Kaiser Hospital system. It was originally designed to screen for depression but is being widely used as a suicide screen.

The PHQ2 asks a client to answer 2 questions and indicate—over the last 2 weeks—how often they have been bothered by either of the following problems:

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things.

- Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.

Answers are given as 0 to 3, using this scale: 0 = Not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; 3 = nearly every day.

If a client responds “not at all” to both questions on the PHQ2, then no additional screening or intervention is required, unless otherwise clinically indicated. If a client responds “yes” to one or both questions on the PHQ2, then an additional assessment should be initiated. Your organization will need to identify the score that necessitates intervention in your particular setting.

3.2.2 Patient Health Questionnaire 9

A more comprehensive version of the Patient Health Questionnaire—called the PHQ9—is used to screen or diagnose depression, measure the severity of symptoms, and measure a client’s response to treatment. The PHQ9 is administered if a client answers “yes” to any of the PHQ2 questions. A study using the PHQ9 found that those who expressed thoughts of death or self-harm were more likely to attempt suicide than those who did not report those thoughts.

Several studies support the use of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9). Item 9 is a universal screening instrument to identify suicide risk:

Item 9: “Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?”

Possible Responses: “Not at all,” “Several days,” “More than half the days,” or “Nearly every day.” (VA/DOD, 2019).

Research at Veteran’s Administration hospitals that included all VHA patients who received the PHQ-9 across care settings found that higher levels of suicidal ideation, as identified by responses on item 9, were associated with increased risk of death by suicide. The number of risk days ranged from 1 to 730 (VA/DOD, 2019).

An increased risk for suicide was found in patients reporting they have been bothered by thoughts of self-harm in the last “several days”, “more than half the days”, and “nearly every day”. Nonetheless, 71.6% of deaths by suicide during the study periods were among those who endorsed “not at all,” highlighting that use of the item 9 alone is likely to result in a number of at-risk patients being missed (VA/DOD, 2019).

Other researchers have examined the relationship between PHQ-9 item 9 scores and death by suicide among civilian outpatients receiving care for depression in mental health and primary care clinics. They found that responses were predictive of both suicide attempts and deaths within the year post-administration. However, as with the Veteran’s Administration study, there were a notable number of suicides among those who denied thoughts of death or self-harm ideation (VA/DOD, 2019).

3.2.3 Columbia Suicide Screen (C-SSRS)

The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) is an evidence-supported screening tool was developed by Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Pittsburgh. The C-SSRS Triage version features questions that help determine whether an individual is at risk for suicide. There are brief versions of the C-SSRS often used as a screening tool (first two questions) that, based on patient response, can lead to additional questions to triage patients. The protocol and the training on how to use it are available free of charge.

The C-SSRS, supports suicide risk screening through a series of simple, plain-language questions that anyone can ask. The answers help users identify whether someone is at risk for suicide, determine the severity and immediacy of that risk, and gauge the level of support that the person needs. Users of the tool ask people (The Columbia Lighthouse Project, 2016):

- Whether and when they have thought about suicide (ideation).

- What actions they have taken—and when—to prepare for suicide.

- Whether and when they attempted suicide or began a suicide attempt that was either interrupted by another person or stopped of their own volition.

3.2.4 EDSAFE Patient Safety Screener

In 2017, the results of the largest ED-based suicide intervention trial ever conducted in the United States was published in JAMA Psychiatry. The study examined how screening in emergency departments, followed by safety planning guidance and periodic phone check-ins led to a 30% decrease in suicide attempts over the 52 weeks of follow-up, compared to standard emergency department care. The five-year Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) study involved nearly 1,400 suicidal patients in eight hospital emergency rooms across seven states (NIMH, 2017).

The ED-SAFE study allowed researchers to assess the impacts of universal suicide risk screening and follow-up interventions in eight emergency departments over 5 years (NIMH, 2023). In the first phase, adult patients seeking care at a participating emergency department received treatment as usual. The second phase introduced universal suicide risk screening—all emergency department patients completed a brief screening tool called the Patient Safety Screener (NIMH, 2023).

The third phrase added a three-part intervention. Patients who screened positive on the Patient Safety Screener completed a secondary suicide risk screening, developed a personalized safety plan, and received a series of supportive phone calls in the following months (NIMH, 2023).

As a result of universal screening, the screening rate rose from about 3% to 84%, and the detection rate of patients at risk for suicide rose from about 3% to almost 6%. Importantly, findings from the third phase showed that it was screening combined with the multi-part intervention that actually reduced patients’ suicide risk. Patients who received the intervention had 30% fewer suicide attempts than those who received only screening or treatment as usual (NIMH, 2023).

The Emergency Medicine Network’s EDSAFE Patient Safety Screener is a brief screening tool, primarily used as part of an initial inpatient nursing assessment in emergency department. This tool can also be used in outpatient and other settings. It contains three questions:

- Over the last 2 weeks, have you felt down, depressed, or hopeless?

- Over the last 2 weeks, have you had thoughts of killing yourself?

- In your lifetime, have you ever attempted to kill yourself? If so, when?

If a client screens positive on the EDSAFE Patient Safety Screener, a secondary screen is recommended to help guide the decision to refer to a mental health specialist. The secondary screen asks:

- Did the patient screen positive on the PSS items—active ideation with a past attempt?

- Has the individual begun a suicide plan?

- Has the individual recently had intent to act on his/her ideation?

- Has the patient ever had a psychiatric hospitalization?

- Does the patient have a pattern of excessive substance use?

- Is the patient irritable, agitated, or aggressive?

3.2.5 Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ)

[Unless otherwise noted, the following information is from the National Institutes of Mental Health, 2024]

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) tool is a brief, validated tool for use among both youth and adults. The Joint Commission has approved the use of the ASQ for all ages. As there are no tools validated for use in kids under the age of 8 years, if suicide risk is suspected in younger children a full mental health evaluation is recommended instead of screening.

The ASQ is free of charge and available in multiple languages. It contains four screening questions that take 20 seconds to administer. In a National Institute of Mental Health study, a “yes” response to one or more of the four questions identified 97% of youth (aged 10 to 21 years) at risk for suicide.

For screening youth, it is recommended that screening be conducted without the parent/guardian present. If the parent/guardian refuses to leave or the child insists that they stay, conduct the screening with the parent/guardian present. For all patients, any other visitors in the room should be asked to leave the room during screening.

Patients who screen positive for suicide risk on the ASQ should receive a brief suicide safety assessment (BSSA) conducted by a trained clinician such as a social worker, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, physician, or other mental health clinician to determine if a more comprehensive mental health evaluation is needed. The BSSA should guide what happens next in each setting.

The ASQ toolkit is organized by the medical setting in which it will be used: emergency department, inpatient medical/surgical unit, outpatient primary care, and specialty clinics.

To access the ASQ screening toolkit click here.

3.3 Gatekeeper Training

[Unless otherwise noted, the following information is from CDC, 2022]

Gatekeeper training programs are peer-support programs that have had success educating the public about suicidal ideation and suicide. Gatekeepers come from all sectors of the community and are trained to identify people who may be at risk for suicide or suicidal behavior and to respond by facilitating referrals to treatment and other support services. Gatekeepers include peers, teachers, coaches, clergy, emergency responders, primary and urgent care providers, and others.

There are many gatekeeper trainings available with varying degrees of evidence. Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) is a widely implemented training program that helps hotline counselors, emergency workers, and other gatekeepers screen and identify individuals with suicidal thoughts or behaviors. The training helps people within the community reach out and assist by safely connecting those in need to available resources.

Gatekeeper training has been a primary component of the Garrett Lee Smith (GLS) Suicide Prevention Program, which has been implemented in 50 states and 50 tribes. A multi-site evaluation assessed the impact of community gatekeeper training as a part of GLS implementation on suicide attempts and deaths among young people ages 10–24. Counties that implemented GLS trainings had significantly lower youth suicide rates up to two years following the training when compared with similar counties that did not offer GLS trainings.

3.4 Screening Children and Adolescents

Suicidal thoughts and attempts have risen in recent years among adolescents and young adults, aged 10-24. In the U.S., suicide is now the second leading cause of death for this age group. In response to a publication from the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF), which stated that there is insufficient evidence to weigh the benefits and harms of screening asymptomatic children and adolescents, the American Academy of Pediatrics is urging clinicians to screen all adolescents for suicide risk despite the USPSTF’s findings that more research is needed to weigh the benefits and harms.

Because of significant age-related racial disparities in childhood suicide, screening has been identified as a health equity issue. Recent research indicates that the suicide rate among those younger than 13 years of age is approximately 2 times higher for Black children compared with white children, a finding observed in both boys and girls (Bridge et al., 2018).

Based on the now substantial evidence base for screening and the recent increase in youth suicidality, there is mounting support for suicide screening as a part of routine healthcare for youth. Currently, there is no standard of care for screening youth for suicidality in emergency department settings, which tend to serve as the frontline of acute healthcare (Scudder et al., 2022).

Common screening tools in the youth population include the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), (both discussed in the previous section), the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ), and the Risk of Suicide Questionnaire (RSQ) (Scudder et al., 2022). The Youth Outpatient Brief Suicide Safety Assessment (BSSA) will also be discussed.

3.4.1 Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ)

The SIQ is a 30-item self-reported suicide-risk screening tool that was developed for high school students in grades 10-12. The 15-item SIQ-JR is used for students in grades 7-9. The tool is most often administered via a written self-reported questionnaire in pediatric EDs, typically for patients with both medical/surgical and psychiatric complaints. Some studies apply it as a gold standard against which to test other, shorter, screening tools (Scudder et al., 2022).

The SIQ assesses suicidal ideation on a 7-point scale with statements about frequency of suicidal thoughts or risk factors. For example, a patient would rank “I thought it would be better if I was not alive” on a scale from “I never had this thought” (0) to “almost every day” (7). These point scales are added up to give rise to a score between 0 and 180 for the SIQ, or 0–90 for the SIQ-JR (Scudder et al., 2022).

A score of 41 or greater on the SIQ, a score of 31 or greater on the SIQ-JR, or an endorsement of a recent suicide attempt constitute a positive screen and warrant further psychiatric evaluation. Nine critical items (six on the SIQ-JR) directly assess serious self-destructive behavior, with endorsement of three or more of these items (two on the SIQ-JR) constituting a positive screen for suicidal ideation, regardless of total score (Scudder et al., 2022).

3.4.2 Risk of Suicide Questionnaire (RSQ)

The RSQ is an older four-item screening tool administered by triage nurses in emergency departments to children between the ages of 8–21 years. The tool was originally developed from 14 potential screening questions from several sources, which were validated among several pediatric clinicians and mental health specialists, as well as a sample of pediatric psychiatric patients and nonpatients. The tool is most often administered via a verbal questionnaire in pediatric EDs, typically for patients with both medical/surgical and psychiatric complaints (Scudder et al., 2022).

The RSQ asks four questions. A positive screen is defined as answering “yes” to any question (Scudder et al., 2022):

- Are you here because you tried to hurt yourself?

- In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?

- Have you ever tried to hurt yourself in the past (other than this time)?

- Has something very stressful happened to you in the past few weeks (a situation that was very hard to handle)?

3.4.3 Youth Outpatient Brief Suicide Safety Assessment (BSSA)

[Modified from the National Institute of Mental Health, 2024]

The Youth Brief Suicide Safety Assessment Guide (BSSA) is included in the Ask Suicide Screening Questions (ASQ) toolkit. It contains suggestions on what questions to ask, examples of how to respond to and ask questions, and what areas should be explored to develop a fuller understanding of an individual’s suicide risk. It also includes ways to safety plan and counsel about access to lethal means. The BSSA is intended to be used when an individual screens positive on the ASQ.

When a pediatric patient screens positive for suicide risk:

- Praise the patient for discussing their thoughts.

- Assess the patient (review patient’s responses from the ASQ).

- Determine the frequency of suicidal thoughts.

- Assess if the patient has a suicide plan*.

- Ask about past self-injury and history of previous suicide attempts.

- Ask about related symptoms (depression, anxiety, hopelessness, lack of joy, isolation, substance or alcohol abuse, sleep patterns, appetite).

- Ask about social support and stressors.

*A detailed plan is concerning. If the plan is feasible (e.g., if they are planning to use pills and have access to pills), this is a reason for greater concern and removing or securing dangerous items (medications, guns, ropes, etc.).

- Interview patient and parent/guardian together.

- If patient is ≥ 18, ask permission for parents to join.

- Ask the parent or guardian if they have noticed changes in their child’s sleep or appetite.

- Does your child use drugs or alcohol?

- Has anyone in your family/close friend network ever tried to kill themselves?

- How are potentially dangerous items stored in your home (guns, medications, ropes, etc.)?

- Does your child have a trusted adult they can talk to?

- Are you comfortable keeping your child safe at home?

- Is there anything you would like to tell me in private?

- Make a safety plan with the patient (include the parent/guardian, if possible).

- Determine disposition (for all positive screens, follow up with patient at next appointment).

- Provide resources to all patients

- 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255), En Español: 1-888-628-9454

- 24/7 Crisis Text Line: Text “HOME” to 741-741

You can access the complete Youth Outpatient Brief Suicide Safety Assessment here.

3.3.4 Signs of Suicide, a School-Based Prevention Program

Signs of Suicide (SOS) is a school-based suicide prevention program that uses screening and education to modify behavior in middle and high school students. It includes screening for elevated depression and substance use disorders. The program is designed to (CDC, 2022):

- increase understanding that major depression is an illness,

- improve awareness of the link between suicide and depression,

- improve attitudes toward intervening with peers showing signs of depression and suicidal ideation, and

- increase help-seeking behavior for students personally experiencing depression and suicidal thoughts.

3.5 Using Screening Information

All persons addressing suicidality among patients at risk must have full knowledge of screening and assessment results, and knowledge of steps taken to work with the patient. To the degree possible, care decisions should be made in a team environment with shared decision making and shared responsibility for care. The team must include the patient and his or her family, whenever possible and appropriate.

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention

If a patient screens positive for suicide risk, a suicide risk assessment should be completed. A patient in acute suicidal crisis must:

- Be kept in a safe healthcare environment under one-to-one observation.

- Not be left alone.

- Be kept away from anchor points that can be used for hanging.

- Not have access to materials that can be used for self-injury.

Immediate care should be provided through the emergency department, inpatient psychiatric unit, respite center, or crisis management department.

Screeners should assess their work environment and identify any items that might be used in a suicide attempt or to harm others. Items used on a daily basis in a hospitals, offices, or clinics might seem innocuous but bell cords, bandages, sheets, restraint belts, plastic bags, scissors, letter openers, elastic tubing, and oxygen tubing can all be used in a suicide attempt.

Importance of Secondary Suicide Risk Screening

In a multicenter study of 1,376 emergency department patients with recent suicide attempts or ideation, an intervention consisting of secondary suicide risk screening by the ED physician, discharge resources, and post-ED telephone calls resulted in a 5% absolute decrease in the proportion of patients subsequently attempting suicide and a 30% decrease in the total number of suicide attempts over a 52-week follow-up period (Miller et al, 2017).

If a screen indicates a person is at risk for suicide, denies or if they minimize risk or decline treatment, ask for permission to contact their friends, family, or outpatient treatment providers. If the event the client declines consent, HIPAA permits a clinician to make these contacts without the person’s permission if the clinician believes the client poses a danger to self or others.

For a client considered to be at lower risk of suicide, a screener should make a direct referral to outpatient health services and follow-up to make sure the client actually keeps the appointment. Expecting the client to follow-up usually does not work.

If the screen indicates a person might be at risk for suicide, a suicide assessment should be completed. A comprehensive evaluation is usually done by an experienced clinician to confirm suspected suicide risk, estimate the immediate danger to the patient, and decide on a course of treatment (SPRC, 2014).

Although an assessment can involve structured questionnaires, they can also include open-ended conversations with a patient and/or friends and family to gain insight into the patient’s thoughts and behavior, risk factors, access to lethal means, history of suicide attempts, protective factors, immediate family support, and medical and mental health history (SPRC, 2014).

Recently, seven new and revised elements of performance (EPs) were applied to all Joint Commission-accredited hospitals, behavioral healthcare, and critical access hospital organizations. One of the requirements states that Joint Commission-accredited organizations must screen for suicidal ideation. The new requirements are intended to improve the quality and safety of care for those who are being treated for behavioral health conditions and those who are identified as high risk for suicide (Joint Commission, 2019).

The new elements of performance are as follows (The Joint Commission, 2019):

- Reduce the risk for suicide by identifying features in the physical environment that could be used to attempt suicide.

- Screen all individuals served for suicidal ideation using a validated screening tool.

- Use an evidence-based process to assess individuals who have screened positive for suicidal ideation. Directly ask about suicidal ideation, plan, intent, suicidal or self-harm behaviors, risk and factors, and protective factors.

- Document individuals’ overall level of risk and the plan to mitigate the risk for suicide.

- Follow written policies and procedures addressing the care of individuals served identified as at risk for suicide.

- Follow written policies and procedures for counseling and follow-up care at discharge.

- Monitor implementation and effectiveness of policies and procedures for screening, assessment, and management of individuals at risk for suicide and improve compliance as needed.

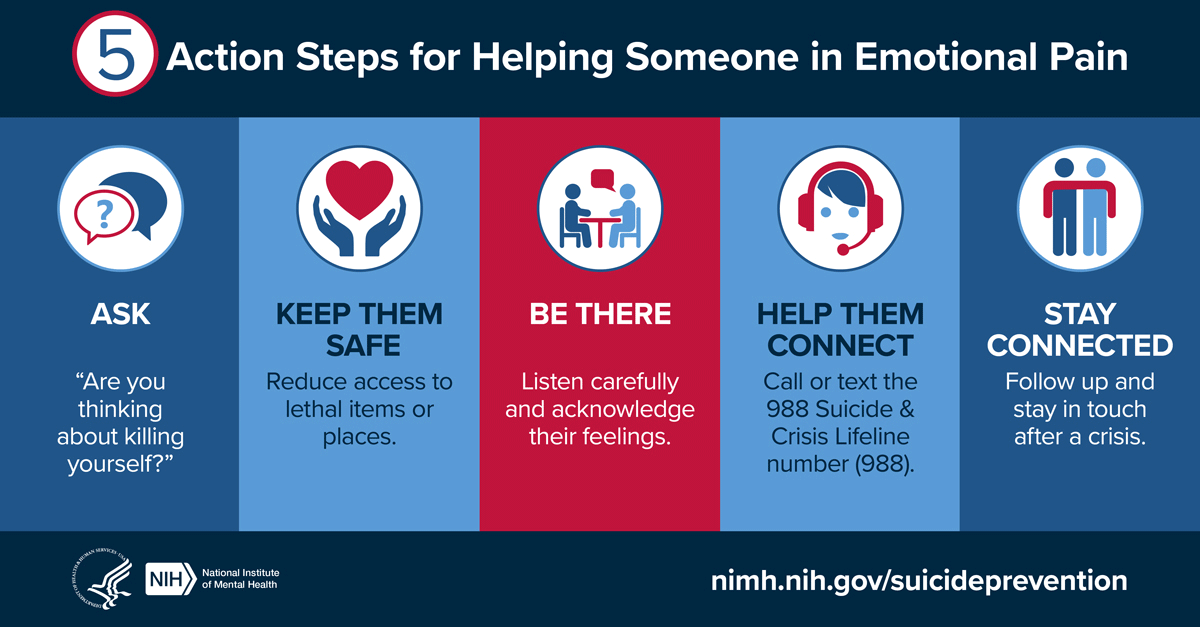

Whether you are a healthcare provider, a mental health professional, or a community member, all of us can make a difference in suicide prevention. The National Institute of Mental Health has published “5 actions steps” anyone can take if you think someone might be at risk for self-harm (NIMH, 2024).

- Ask: “Are you thinking about killing yourself?” It’s not an easy question, but studies show that asking at-risk individuals if they are suicidal does not increase suicides or suicidal thoughts.

- Keep Them Safe: Reducing a suicidal person’s access to highly lethal items or places is an important part of suicide prevention. While this is not always easy, asking if the at-risk person has a plan and removing or disabling the lethal means can make a difference.

- Be There: Listen carefully and learn what the individual is thinking and feeling. Research suggests acknowledging and talking about suicide may reduce rather than increase suicidal thoughts.

- Help Them Connect: Save the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline number (call or text 988) in your phone so they’re there if you need them. You can also help make a connection with a trusted individual like a family member, friend, spiritual advisor, or mental health professional.

- Stay Connected: Staying in touch after a crisis or after being discharged from care can make a difference. Studies have shown the number of suicide deaths goes down when someone follows up with the at-risk person.

3.6 Additional Screening and Assessment Tools

Dr. Marsha Linehan and her colleagues at the University of Washington Behavioral Research and Therapy Clinics has published a comprehensive list of screening and risk assessment tools. The tools are available for research, clinical, and educational uses at no charge.

- Linehan Risk Assessment & Management Protocol (LRAMP)

- University of Washington Risk Assessment Protocol (UWRAP)

- Borderline Symptom List (BSL)

- The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL Scale)

- Demographic Data Scale (DDS)

- NIMH S-DBT Diary Card

- Imminent Risk and Action Plan

- Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury

- Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII)

- Parental Affect Test

- The Reasons for Living Inventory (RFL)

- Social History Interview (SHI)

- Substance Abuse History Interview (SAHI)

- Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire (SBQ)

- Therapist Interview (TI)

- Treatment History Interview (THI)

To access these screening and assessment tools in their entirety, click here.