The most critical aspect of pain assessment is that it be done on a regular basis using a standard format. Pain should be re-assessed after each intervention to evaluate its effect and determine whether an intervention should be modified. The time frame for re-assessment should be directed by the needs of the patient and the hospital or unit policies and procedures.

A self-report by the patient has traditionally been the mainstay of pain assessment, although family caregivers can be used as proxies for patient reports, especially in situations in which communication barriers exist (eg, cognitive impairment, language). Family members who act as proxies typically report higher levels of pain than patient self-reports.

Both physiologic and behavioral responses can indicate the presence of pain and should be noted as part of a comprehensive assessment, particularly following surgery. Physiologic responses include tachycardia, increased respiratory rate, and hypertension. Behavioral responses include splinting, grimacing, moaning or grunting, distorted posture, and reluctance to move. A lack of physiologic responses or an absence of behaviors indicating pain may not mean there is an absence of pain.

Good communication between clinician and patient is critical and good documentation improves communication among clinicians about the current status of the patient’s pain and responses to the plan of care. Documentation is also used as a means of monitoring the quality of pain management within the institution.

In the absence of an objective measure, pain is a subjective individual experience. How we respond to pain is related to genetic factors as well as cognitive, motivational, emotional, and psychological states. Pain response is also related to gender, experiences and memories of pain, cultural and social influences, and general health (Sessle, 2012).

Pain Assessment Tools

Selecting a pain assessment tool should be, when possible, a collaborative decision between patient and provider to ensure that the patient is familiar with the tool. If the clinician selects the tool, consideration should be given to the patient’s age; physical, emotional, and cognitive status; and personal preferences. Patients who are alert but unable to talk may be able to point to a number or a face to report their pain (Wells et al., 2008).

Pain Scales

Many pain intensity measures have been developed and validated. Most measure only one aspect of pain (ie, pain intensity) and most use a numeric rating. Some tools measure both pain intensity and pain unpleasantness and use a sliding scale that allows the patient to identify small differences in intensity. The following illustrations show some commonly used pain scales.

Visual Analog Scale

The Visual Analogue Scale. The left endpoint corresponds to “no pain” and the right endpoint (100) is defined as “pain as

intense as it can be.”

†A 10-cm baseline is recommended for VAS scales.

Source: Adapted from Acute Pain Management Guideline

Panel, 1992 (AHCPR, 1994). Public domain.

Numeric Rating Scale

The Numeric Rating Scale. Indicated for adults and children (>9 years old) in all patient care settings in which patients are able to

use numbers to rate the intensity of their pain. The NRS consists of a straight horizontal line numbered at equal intervals from 0 to 10 with anchor

words of “no pain,” “moderate pain,” and “worst pain.”

Source: Adapted from Acute Pain Management Guideline

Panel, 1992 (AHCPR, 1994). Public domain.

The Pain Scale for Professionals

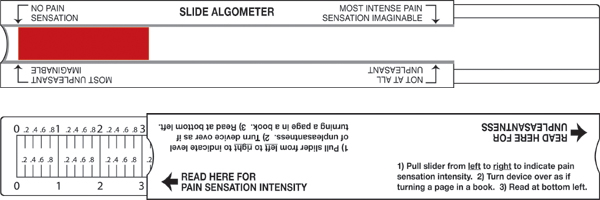

The Pain Scale for Professionals. The patient slides the middle part of the device to the right and left and views the amount of red as a measure of pain sensation. The arrow at the left means “no pain sensation” and the arrow at the right indicates the “most intense pain sensation imaginable.” The sliding part of the device is moved on a different axis for the unpleasantness scale. The arrow at the left means “not at all unpleasant” and the arrow at the right represents pain that is the “most unpleasant imaginable.”

Source: The Risk Communication Institute. Used with permission.

|

Verbal Rating Scale |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Description |

Points Assigned |

|

|

No pain |

0 |

|

|

Mild pain |

2 |

|

|

Moderate pain |

5 |

|

|

Severe pain |

10 |

|

For patients with limited cognitive ability, scales with drawings or pictures, such as the Wong-Baker FACES™ scale, are useful. Patients with advanced dementia may require behavioral observation to determine the presence of pain.

Wong-Baker FACES™ Pain Rating Scale

The Wong-Baker FACES scale is especially useful for those who cannot read English and for pediatric patients.

Source:

Copyright 1983, Wong-Baker FACES™ Foundation, www.WongBakerFACES.org. Used with permission.

Pain Questionnaires

Pain questionnaires typically contain verbal descriptors that help patients distinguish different kinds of pain. One example, the McGill Pain Questionnaire asks patients to describe subjective psychological feelings of pain. Pain descriptors such as pulsing, shooting, stabbing, burning, grueling, radiating, and agonizing (and more than seventy other descriptors) are grouped together to convey a patient’s pain response (Srouji et al., 2010).

The questionnaire combines a list of questions about the nature and frequency of pain with a body-map diagram to pinpoint its location. It uses word lists separated into four classes (sensory, affective, evaluative, and miscellaneous) to assess the total pain experience. After patients are finished rating their pain words, a numerical score is calculated, called the “Pain Rating Index.” Scores vary from 0 to 78, with the higher score indicating greater pain (Srouji et al., 2010).

Assessing Pain in Special Populations

Assessing Pain in Cognitively Impaired Adults

The assessment of pain in the cognitively impaired patient can be a significant challenge. Cognitively impaired patients tend to voice fewer pain complaints but may become agitated or manifest unusual or sudden changes in behavior when they are in pain. Clinicians and caregivers may have difficulty knowing when these patients are in pain and when they are experiencing pain relief. This makes the patient vulnerable to both under-treatment and over-treatment. Failure to report pain should not be assumed to mean the absence of pain.

In the absence of accurate self-report, observational tools based on behavioral cues have been developed. The most structured observational tools are based on guidance published by the American Geriatrics Society, which describe six domains for pain assessment in cognitively impaired adults:

- Facial expression

- Negative vocalization

- Body language

- Changes in activity patterns

- Changes in interpersonal interactions

- Mental status changes (Lichtner et al., 2014)

The interpretation of these behaviors can be complex, due to overlap with other common symptoms such as boredom, hunger, anxiety, depression, or disorientation. This increases the complexity of accurately identifying of pain in patients with dementia and raises questions about the validity of existing instruments. As a result, there is no clear guidance for clinicians and staff on the effective assessment of pain, nor how this should inform treatment and care decision-making (Lichtner et al., 2014).

Patient self-report remains the gold standard for pain assessment but in nonverbal older adults the next best option, from a user-centered perspective, becomes the assessment of a person who is most familiar with the patient in everyday life in a hospital or other care setting; this is sometimes referred to as a “silver standard” (Lichtner et al., 2014).

Online Resource

A thorough review of pain assessment tools for nonverbal older adults by Herr, Bursch, and Black of the University of Iowa is available at http://prc.coh.org/PainNOA/OV.pdf.

Assessing Pain in Children

Despite decades of research and the availability of effective analgesic approaches, many children continue to experience moderate to severe pain, especially after hospitalization. Overall, the factors affecting children’s pain management are influenced by cooperation (nurses, doctors, parents, children), child (behavior, diagnosis, age), organization (lack of routine instructions for pain relief, lack of time, lack of pain clinics), and nurses (experience, knowledge, attitude) (Aziznejadroshan et al., 2016).

Pain evaluation in small children can be difficult. Previous experiences, fear, anxiety, and discomfort may alter pain perception; thus, poor agreement between instruments and raters is often the norm. In children younger than 7 years of age and in cognitively impaired children, evaluation of pain intensity through self-report instruments can be inaccurate due to poor understanding of the instrument and poor capacity to translate the painful experience into verbal language; therefore, complementary observational pain measurements should be used to assess pain intensity (Kolosovas-Machuca et al., 2016).

Three methods are commonly used to measure a child’s pain intensity:

- Self-reporting: what a child is saying.

- Behavioral measures: what a child is doing (motor response, behavioral responses, facial expression, crying, sleep patterns, decreased activity or eating, body postures, and movements).

- Physiologic measures: how the body is reacting (changes in heartrate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, palmar sweating, respiration, and sometimes neuroendocrine responses (Srouji et al., 2010).

Children’s capability to describe pain increases with age and experience, and changes throughout their developmental stages. Although observed reports of pain and distress provide helpful information, particularly for younger children, they are reliant on the individuals completing the report (Srouji et al., 2010).

Back Next