Certain pain syndromes are pervasive. Low back pain, migraine headaches, post operative pain, cancer pain, and pain associated with arthritis are some of the most common reasons patients seek medical care for pain.

Low Back Pain

Low back pain affects approximately 80% of people at some stage in their lives. If low back pain becomes chronic it often results in lost wages and additional medical expenses and can increase the risk of incurring other medical conditions (Chou et al., 2016).

Low back pain is the fifth most common reason for all physician visits. Approximately one-quarter of U.S. adults reported having low back pain lasting at least 1 day in the past 3 months, and more than 7% reported at least one episode of severe low back pain in the previous year.

Clinically, the natural course of low back pain is usually favorable; acute low back pain frequently disappears within 1 to 2 weeks. Any of the spinal structures, including intervertebral discs, facet joints, vertebral bodies, ligaments, or muscles could be an origin of back pain—which is, unfortunately, difficult to determine. In those cases in which the origin of back pain cannot be determined, the diagnosis given is nonspecific low back pain (Aoki et al., 2012).

Headache Pain

I’ve worked as a physical therapist for more than 20 years and didn’t know headaches were such a big problem. I don’t recall learning about headaches in school and I’ve never even thought about them in clinical practice, except in the most general terms—even with stroke patients!

Geriatric Specialist, 2014

Headache is one of the most common neurologic disorders and accounts for many visits to both general physicians and neurologists. In 2018 the International Headache Society published the third edition of its International Classification of Headache Disorders. The guide divides headache disorders into three categories:

- Primary headaches (migraine, tension-type, trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, and other primary headache disorders)

- Secondary headaches—headaches attributed to:

- trauma or injury to the head and/or neck

- cranial and or cervical vascular disorder

- non-vascular intracranial disorder

- a substance or its withdrawal

- infection

- disorder of homeostasis

- disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth or other facial or cervical structure

- psychiatric disorder

- Painful cranial neuropathies, other facial pain, and other headaches (IHS, 2018)

Migraine and tension-type headaches are the most prevalent primary headache disorders (Oshinaike et al., 2014). Although medication overuse headache is considered separately by some (Schmid et al., 2013), beginning in 2016 the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study has removed it as a cause and characterizes it as a sequela of migraine and tension-type headaches (GBD, 2016).

The 2016 GBD Study ranks tension-type headaches and migraine as the third and sixth most common diseases in the world (dental caries in permanent teeth were first). Globally, migraine is the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs), behind only low back pain. Although many questions remain about the occurrence of headaches, especially among children and adolescents, there is more data available all the time, yet is often ignored and headache remains undertreated globally (GBD, 2016; Steiner et al., 2018).

The medical treatment of patients with chronic primary headache syndromes is particularly challenging. Valid studies are few, and in many cases even higher doses of preventive medication are ineffective and adverse side effects frequently complicate the course of medical treatment. There is no single standard of care for patients presenting with primary chronic headache symptoms (Martelletti et al., 2013).

Postoperative Pain

More than 80% of patients who undergo surgical procedures experience acute postoperative pain and approximately 75% of those…report the severity as moderate, severe, or extreme.

Guidelines on the Management of Postoperative Pain

Evidence suggests that fewer than 50% of surgical patients receive adequate postoperative pain relief. Inadequately controlled pain negatively affects quality of life, function, and functional recovery, the risk of post surgical complications, and the risk of persistent pain following surgery (Chou et al., 2016a).

Noting that quality management strategies exist to reduce and manage postoperative pain, strategies that can and should be employed before, during, and after surgery, the American Pain Society spearheaded work to establish a comprehensive set of guidelines for managing postoperative pain (Chou et al., 2016a).

The final 32 recommendations cover a range of relevant elements and include:

- Provision of patient and family-centered education and information

- Comprehensive pre-operative evaluations

- Adjustment of pain management plan on the basis of adequacy of pain relief and presence of adverse events

- Use of validated pain assessment tools to track treatment efficacy and make adjustments

- Offering multi-modal analgesia, or the use of a variety of analgesic medications and techniques combined with non-pharmacological interventions (Chou et al., 2016a)

The recommendations cover specific pharmacological and non-pharmacological substances and modalities. There is significant detail provided for use of drugs and the overall thrust is toward a multi-modal program that acknowledges that pain management is an evolving process (Chou et al., 2016a).

Pain Associated with Cancer

Pain occurs in 20% to 50% of patients with cancer (NCI, 2017). It is one of the most feared and common symptoms of a variety of cancers and is a primary determinant of the poor quality of life in cancer patients (Bali et al., 2013).

Cancer-associated pain—particularly neuropathic pain—is often resistant to conventional therapeutics, whose application may be severely limited due to side effects (Bali et al., 2013). In advanced stage, moderate to severe pain affects roughly 80% of cancer patients. Younger patients are more likely to experience cancer pain and pain flares than are older patients (NCI, 2017).

Research from Europe, Asia, Australia, and the United States indicates that cancer patients are commonly undertreated for pain, both as inpatients and outpatients—sometimes receiving no analgesia at all. Regardless of what stage the cancer has reached, it is necessary to determine the prevalence of pain in specific cancer types, both to raise awareness among clinicians and to improve patient management (Kuo et al., 2011).

Breakthrough pain is a transitory increase or flare of pain in otherwise relatively well-controlled acute or chronic pain (NCI, 2017). It is common in cancer patients.

Incident pain is a type of breakthrough pain related to certain defined activities or factors; an example is body movement’s contributing to increased vertebral pain from metastatic disease. It is often difficult to treat such pain effectively because of its episodic nature. In one study, 75% of patients experienced breakthrough pain; 30% of this pain was incidental, 26% was non-incidental, 16% was caused by end-of-dose failure, and the rest had mixed etiologies (NCI, 2017).

Effective pain management can generally be accomplished by employing a comprehensive plan that involves screening to recognize pain early, proper identification of types of pain experienced, determining if pain requires pharmacologic or other modalities of treatment, identifying the optimal balance of treatment options, proper patient education about treatment, and continued monitoring (NCI, 2017).

Pain Associated with Arthritis

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions are a leading cause of pain and disability in adults in the United States. By 2030 about 25% of Americans are expected to be living with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions. The negative consequences, including pain, reduced physical ability, depression, and reduced quality of life can impact the physical functioning and psychological well-being of those living with the conditions (Schoffman et al., 2013).

Osteoarthritis

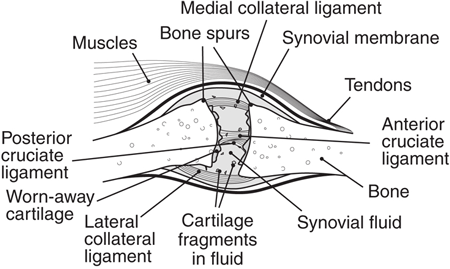

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a disease that damages the slippery tissue that covers the ends of bones in a joint. This allows bones to rub together and the rubbing causes pain, swelling, and loss of motion of the joint. Over time, the joint may lose its normal shape. The condition can cause bone spurs to grow on the edges of the joint. Bits of bone or cartilage can break off and float inside the joint space, which causes more pain and damage (NIAMS, 2016).

Osteoarthritic Knee Joint Showing Spurs

Source: NIH.gov.

With OA, joint pain and stiffness worsens over time. OA is the most common form of arthritis and it affects close to 27 million Americans. After the age of 65, 60% of men and 70% of women experience OA (Van Liew et al., 2013).

Best practice guidelines for chronic osteoarthritis focus on self-management: weight control, physical activity, and pharmacologic support for inflammation and pain. Obesity is an independent risk factor for osteoarthritis and there is an interactive relationship among osteoarthritis, obesity, and physical inactivity (Dean & Hansen, 2012). Recent research suggests the relationship between obesity and arthritis may be more complex than originally thought (DeClercq et al., 2017).

Physical exercise has become widely recommended for individuals with OA because it has been related to longevity. A meta-analysis on treatments found that exercise programs reduced pain, improved physical functioning, and enhanced quality of life among individuals with OA (Van Liew et al., 2013). Despite this, close to 44% of adults with arthritis report not engaging in exercise.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

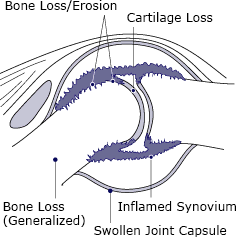

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease that involves inflammation of the thin layer of tissue lining a joint space (synovium) with progressive erosion of bone, leading in most cases to misalignment of the joint, loss of function, and disability. RA is among the most disabling forms of arthritis. It affects 1% of the U.S. adult population (about 2 million people). RA tends to affect the small joints of the hands and feet in a symmetric pattern, but other joint patterns are often seen (Sarmiento-Monroy et al., 2012).

Anyone can get RA, though it occurs more often in women. Rheumatoid arthritis often starts in middle age and is common in older people, but children and young adults can also get it. The exact cause of rheumatoid arthritis is not known, but may include genes, environmental factors, and hormones. With RA, individuals immune systems attack their own body tissues. Treatment may involve regular doctor visits, medication, surgery, and complementary therapies (NIAMS, 2017).

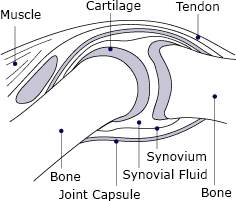

Normal Joint

Joint Affected by Rheumatoid Arthritis

Illustrations of normal joint and joint affected by rheumatoid arthritis. Source: NIH, public domain.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory joint disease characterized by stiffness, pain, swelling, and tenderness of the joints as well as the surrounding ligaments and tendons. It affects men and women equally, typically presents between the ages of 30 and 50, and is associated with psoriasis in approximately 25% of patients. Cutaneous disease usually precedes the onset of psoriatic arthritis by an average of 10 years in the majority of patients, but 14% to 21% of patients with psoriatic arthritis develop symptoms of arthritis prior to the development of skin disease. Psoriatic arthritis has a highly variable presentation, which can range from a mild, nondestructive arthritis to a severe, debilitating, erosive joint disease (Lloyd et al., 2012).

No one knows what causes psoriatic arthritis. Researchers believe that both genes and environment are involved, and it is more common in Caucasians than African Americans or Asian Americans. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to help prevent joint damage (NIAMS, 2017a).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs help with symptomatic relief, but they do not alter the disease course or prevent disease progression. Intra-articular steroid injections can be used for symptomatic relief. Physical or occupational therapy may also be helpful in symptomatic relief (Lloyd et al., 2012). For forms that are persistent or affect multiple joints, other classes of drugs may be effective. Exercise, heat and cold therapies, relaxation exercises, splints and braces, and assistive devices can help (NIAMS, 2017a).

Back Next