We have an emergency on our hands. The fast-moving opioid overdose epidemic continues and is accelerating. We saw, sadly, that in every region, in every age group of adults, in both men and women, overdoses from opioids are increasing.

Anne Schuchat, March 2018

CDC Acting Director

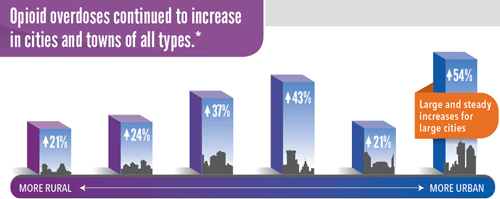

*From left to right, the categories are: (1) non-core (non-metro), (2) micropolitan (non-metro), (3) small metro, (4) medium metro, (5) large fringe metro, (6) large central metro.

Source: CDC’s Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance (ESOOS) Program, 16 states reporting percent changes from July 2016 through September 2017.

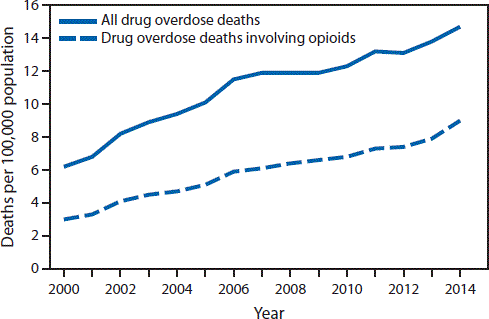

The United States is in the midst of an opioid overdose epidemic (see also Module 7). Opioids (including prescription opioids, heroin, and fentanyl) killed more than 42,000 people in 2016, more than any year on record. Forty percent of all opioid overdose deaths involve a prescription opioid (CDC, 2017a). In the year between the third quarter of 2016 and the third quarter of 2017 opioid overdoses across the nation jumped by about 30% (Stein, 2018).

Drug overdose deaths and opioid-involved deaths continue to increase in the United States. The majority of drug overdose deaths (66%) involve an opioid. In 2016 the number of overdose deaths involving opioids (including prescription opioids and heroin) was 5 times higher than in 1999. From 2000 to 2016, more than 600,000 people died from drug overdoses. On average, 115 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose (CDC, 2017a).

We now know that overdoses from prescription opioids are a driving factor in the 16-year increase in opioid overdose deaths. The amount of prescription opioids sold to pharmacies, hospitals, and doctors’ offices nearly quadrupled from 1999 to 2010, yet there had not been an overall change in the amount of pain that Americans reported. Deaths from prescription opioids—drugs like oxycodone, hydrocodone, and methadone—have more than quadrupled since 1999 (CDC, 2017a).

An unfortunate consequence of the increased availability of opioid analgesics is their use in ways that are unsafe or unintended. OxyContin for example, which was designed as a slow-release, oral medication is being crushed, then snorted or injected, with lethal consequences. In an attempt to stay ahead of the illicit drug trade, new formulations have been designed that are intended to deter some of these abuses. For example, a new formulation of OxyContin releases from 21% to 48% less opioid when tampered (milled, manually crushed, dissolved, and boiled) than the original version (Raffa et al., 2012).

Paradoxically, despite an enormous rise in spending and prescription, there is limited evidence to support the efficacy of opioids in chronic non-cancer pain management. In a European survey on chronic pain, 15% of respondents felt that their medications were not very or not at all effective (Xu & Johnson, 2013). Systematic reviews have suggested limited efficacy of long-term opioid therapy over short-term treatment or placebo, while an evidence review by the Institute of Medicine concluded that the effectiveness of opioids as pain relievers, especially over the long term, is somewhat unclear (Xu & Johnson, 2013).

The enormous increase in the availability of prescription pain medications is drawing new users to these drugs, and changing the geography and age-grouping of opiate-related overdoses. Prescription opioid–related overdoses currently represent the leading cause of death in the United States for 35- to 54-year-olds (Unick et al., 2013).

Opiate-Related Overdose and Poisoning

Poisoning is now the leading cause of death from injuries in the United States and nearly 9 out of 10 poisoning deaths are caused by drugs.

Margaret Warner, 2011

One of the Healthy People 2020 objectives is to reduce fatal poisonings in the United States. This goal was set because, during the Healthy People 2010 tracking period from 1999 to 2008, the drug poisoning death rate increased among all age groups. In 2008 alone, over 41,000 people died as a result of a poisoning and 80% of drug poisoning deaths that year involved opioid analgesics (Warner et al., 2011). More persons died from drug overdoses in the United States in 2014 than during any previous year on record. (CDC, 2016b).

Opiate-Related Overdose Deaths

CDC, 2016b.

In Michigan, during the reporting period covering the years 1999 and 2014:

- The total number of drug poisoning deaths has leveled in recent years but there has been a steady increase since 2012.

- The age-adjusted rate for heroin poisoning deaths nearly doubled between 2012 and 2014, while the age-adjusted rate for opioid analgesics poisoning death increased slightly.

- The age-adjusted death rate involving heroin was nearly 3.5 times higher for men than women in 2014.

- Young adults aged 25 to 34 years had the highest death rate involving heroin and adults aged 35 to 44 years had the highest death rate involving opioids (MDHHS, 2014). In 2015 35- to 44-year-olds also had the highest prescription drug overdose death rate.. (MDHHS, 2017)

Tolerance, Dependence, and Addiction

The predictable consequences of long-term opioid administration—tolerance and physical dependence—are often confused with psychological dependence (addiction) that manifests as drug abuse. This misunderstanding can lead to ineffective prescribing, administering, or dispensing of opioids for cancer pain.

Tolerance

Tolerance is a state of adaptation in which a drug becomes less effective over time, which means a larger dose is needed to achieve the same effect. Tolerance occurs when a drug causes the brain to release large amounts of dopamine. In some cases, this occurs almost immediately—especially when drugs are smoked or injected—and the effects can last much longer than those produced by natural rewards.

The resulting effects on the brain’s pleasure circuit dwarfs those produced by naturally rewarding behaviors. The brain adapts to these overwhelming surges in dopamine by producing less dopamine or by reducing the number of dopamine receptors in the reward circuit. This reduces the user’s ability to enjoy not only the drugs but also other events in life that previously brought pleasure. This decrease compels the person to keep abusing drugs in an attempt to bring the dopamine function back to normal, but now larger amounts of the drug are required to achieve the same dopamine high (NIDA, 2016).

Analgesic tolerance is the need to increase the dose of opioid to achieve the same level of analgesia. Analgesic tolerance may or may not be evident during opioid treatment and does not equate with addiction (PPRG, 2013b).

Dependence and Addiction

It is often said that addiction is easy to recognize, that it rarely arises during the treatment of pain with addictive drugs, and that cases of addiction during pain treatment can be managed in much the same way as other addictions, but such generalizations grossly oversimplify the real situation.

International Association for the Study of Pain

Clarifying the difference between dependence and addiction is important to better understand the issues in opioid use and abuse. Dependence is the physical tolerance of the drug that requires increased amounts of the drug to achieve the desired response. Withdrawal of the drug will result in physical symptoms such as shaking, tremors, nausea, and vomiting. Addiction is a behavioral disorder that refers to the emotional desire for the drug and the desired effects it brings, which often creates strong drug-seeking behaviors. Generally, those who are dependent on opioids will vary between feeling sick without the drug and the desired high after taking the drug. Being addicted to the drug will motivate a person to do whatever it takes to get and take the drug to avoid the dreaded withdrawal symptoms.

Withdrawal symptoms include the following:

- Intense drug cravings

- Depression, withdrawal fears, anxiety

- Sweating, watery eyes, runny nose

- Restlessness, yawning

- Diarrhea

- Fever and chills

- Muscle spasms

- Tremors and joint pain

- Stomach cramps

- Nausea and vomiting

- Elevated heart rate and blood pressure (NIDA, 2015; Kosten & O’Connor, 2013)

People at risk for opioid dependence and addiction are seen in every age, gender, ethnicity, and culture. Physical dependence varies. A genetic component has been identified that influences how quickly a person may slide from occasional use to physical need and addiction to the drug (Kreek et al., 2005). Susceptible populations have typically included the homeless, alcoholics, and those with personality or mental health disorders who look for a way to block the emotional pain of life stressors. Healthcare professionals, who experience great work stress, have a higher risk of becoming dependent or addicted to opiates following back or other injuries and having easier access to narcotics in their work setting (Kenna & Lewis, 2008).

Addiction may also be referred to by terms such as drug dependence and psychological dependence. Physical dependence and tolerance are normal physiologic consequences of extended opioid therapy for pain and should not be considered addiction. Pseudo-addiction is a pattern of drug-seeking behavior by pain patients who are receiving inadequate pain management that can be mistaken for addiction (PPRG, 2013b).

Addiction affects multiple brain circuits, including those involved in reward and motivation, learning and memory, and inhibitory control over behavior. As with any other disease, vulnerability to addiction differs from person to person. In general, the more risk factors an individual has, the greater the chance that taking drugs will lead to abuse and addiction. The overall risk for addiction is impacted by the biologic makeup of the individual and can be influenced by gender, ethnicity, developmental stage, and the surrounding social environment. Adolescents and individuals with mental disorders are at greater risk of drug abuse and addiction than the general population.

Although taking drugs at any age can lead to addiction, the earlier individuals begin to use drugs the more likely they are to progress to more serious abuse. This may reflect the harmful effect that drugs can have on the developing brain; it also may result from a constellation of early biologic and social vulnerability factors, including genetic susceptibility, mental illness, unstable family relationships, and exposure to physical or sexual abuse. Still, the fact remains that early use is a strong indicator of problems ahead—among them, substance abuse and addiction (NIDA, 2016).

Smoking a drug or injecting it into a vein increases its addictive potential. Both smoked and injected drugs enter the brain within seconds, producing a powerful rush of pleasure. However, this intense high can fade within a few minutes, taking the abuser down to lower, more normal levels. It is a starkly felt contrast, and scientists believe that this low feeling drives individuals to repeated drug abuse in an attempt to recapture the highly pleasurable state (NIDA, 2014).

Opioids are highly addictive and rates of addiction among patients receiving opioids for the management of pain vary from 1% to 50%, which suggests uncertainty about what addiction really is and how often it occurs (IASP, 2013). The enormous increase in the availability of prescription opioids is fuelling a rise in addiction nationally, introducing new users to these drugs and changing the geography of opiate-related overdoses (Unick et al., 2013).

To distinguish between misuse behaviors and addiction in chronic pain patients, assess the relationship between opioid dose titration and functional restoration. In this approach, in response to aberrant “drug-seeking” behaviors (ie, continued complaints of pain or requests for more medication), the clinician increases the opioid dose in an effort to provide analgesia. Improvements in functional outcomes and quality of life, with fewer problematic behaviors, indicate that active addiction is not present. In this case, drug-seeking behaviors may reflect pseudo-addiction, therapeutic dependence, or opioid tolerance. Effective dosing results in functional restoration (Chang & Compton, 2013).