Safety is a global concept that encompasses efficiency, security of care, reactivity of caregivers, and satisfaction of patients and relatives.

Garrouste-Orgeas, 2012

Modern systems approaches to reduce errors and improve efficiency have their roots in the manufacturing quality and process control principles developed by renowned statistician W. Edwards Deming, engineers Joseph M. Juran and Kaoru Ishikawa, and former Secretary of Commerce and quality management champion Malcolm Baldrige, among others.

When a manufacturing process is standardized, it often leads to greater efficiency and fewer mistakes. It’s no wonder than some of these same processes (systems) for finding, analyzing, and preventing manufacturing errors are being applied to healthcare.

An important contributor to medical errors is lack of communication between co-workers, departments, shifts, and even among different organizations and levels of care. Doctors, nurses, and others see a particular patient through their own professional prisms and attend to different aspects of the patient’s care. This makes creating a culture of safety a huge organizational challenge, one that needs to be evaluated constantly and systematically. According to the IOM [sic], most medical errors are the result of systems failures that require analysis on a systems level to understand their cause and to promote corrective action.

Indeed, Garrouste-Orgeas and colleagues (2012) wrote,

Preventive strategies are more likely to be effective if they rely on a system-based approach, in which organizational flaws are remedied, rather than a human-based approach of encouraging people not to make errors.

Root Cause Analysis

Root cause analysis (RCA) is a systems approach that asks three questions that provide the framework for information collection?

- What is the problem?

- Why did it happen?

- What can be done to prevent it from occurring again?

According to the book Internal Bleeding, “RCA attempts to write a second story about the actions that led to error—to look past the obvious . . . scapegoats and find the other culprits, however deeply they may be embedded in the system” (Wachter & Shojania, 2004).

In 1997 the Joint Commission (then called the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, or JCAHO) mandated the use of root cause analysis in the investigation of sentinel events or medical errors in accredited hospitals. There are two main categories of error:

- Active error, errors occurring at the point of interface between humans and a complex system

- Latent error, the hidden problems within healthcare systems that contribute to adverse events (AHRQ, 2019c)

RCAs should generally follow a prespecified protocol that begins with data collection and reconstruction of the event in question through record review and participant interviews. A multidisciplinary team should then analyze the sequence of events leading to the error, with the goals of identifying how the event occurred (through identification of active errors) and why the event occurred (through systematic identification and analysis of latent errors). The ultimate goal of RCA, of course, is to prevent future harm by eliminating the latent errors that so often underlie adverse events. (AHRQ, 2019c).

The term root cause analysis, or RCA, is widely used but can be considered misleading. Often there will be multiple errors or system flaws that converge for a critical incident to impact the patient, and labeling one or even a few of them as “causes” can put undue emphasis on them and obscure the overall relationship among all of them. For this reason, it has been suggested that the term root cause analysis should be replaced with “system analysis” (AHRQ, 2019c).

Although one of the most widely used approaches to making patient safety improvements, the effectiveness of root cause analysis has been questioned for not providing sustainable system-level solutions and other problems (AHRQ, 2019; Kellogg et al., 2017; Peerally et al., 2017).

Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycle

Another system approach to eliminating medical errors is called Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) approach, devised by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. This strategy has been widely used by the Institute and many other healthcare organizations. One of the unique features of this strategy is the acknowledgement that change is cyclical in nature and benefits from small and frequent PDSAs rather than big and slow ones, before changes are made system-wide (IHI, 2017).

The PDSA cycle tests a change by “developing a plan to test the change (Plan), then carrying out the test (Do), observing and learning from the consequences (Study), and determining what modifications should be made to the test (Act)” (IHI, 2017).

IHI Open School: Whiteboard: PDSA in Everyday Life (Part 1) [4:45]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-ceS9Ta820

Published March 28, 2012

The TeamSTEPPS Approach

Another systems approach to the problem of medical errors is the Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) approach. A key point is that, even though the delivery of care requires teamwork, members of these teams are rarely trained together and they often come from separate disciplines and diverse educational programs (King et al., 2008).

Given the interdisciplinary nature of healthcare and the necessity for cooperation among those who perform it, teamwork is critical to ensure patient safety. Teams make fewer mistakes than individuals, especially when each team member knows his or her responsibilities. Simply conducting training or installing a team structure does not ensure that the team will operate effectively (King et al., 2008).

There are three phases to the TeamSTEPPS approach:

- Phase I involves assessment and setting the stage.

- Phase II includes planning, training, and implementation.

- Phase III sustains and spread improvements in teamwork performance, clinical processes, and outcomes. (King et al., 2008)

Lean Six Sigma for Healthcare

Lean Six Sigma is the combination of two methodologies, Lean and Six Sigma. Lean attempts to eliminate waste within a process, and Six Sigma (named for six standard deviations from the mean — three above and three below) attempts to reduce variation and defects (AHRQ HIT, 2008).

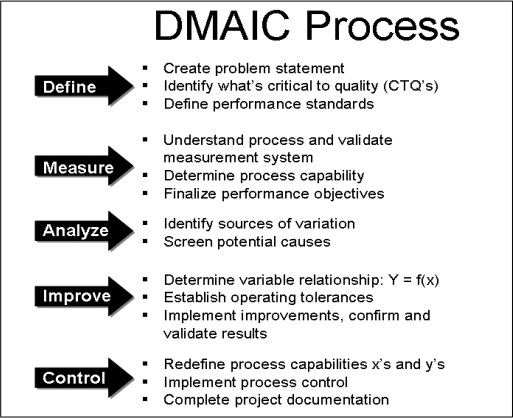

Central to Lean Six Sigma is the Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control (DMAIC) lifecycle (see below).

Lean Six and the DMAIC Lifecycle

Source: Meliones et al., 2008.

Lean Six Sigma is the gold standard manufacturing system for many Fortune 500 companies; however, it is a large, complicated process requiring extensive training to implement.

Nevertheless, Lean Six Sigma can be used to decrease medical errors and improve outcomes. In one example, North Mississippi Medical Center reduced the number of prescription instruction errors in discharge documents by 50% using Lean Six Sigma, according to American Society for Quality (ASQ, n.d.). In fact, Six Sigma programs incorporating some Lean principles were shown to have positive results on:

- Surgery turnaround time

- Clinic appointment access

- Hand hygiene compliance

- Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery

- Scheduling radiology procedures

- Catheter-associated bloodstream infections

- Meeting CMS cardiac indictors

- Hospital-acquired urinary tract infections

- Operating room throughput

- Coagulation testing in the laboratory

- Handoff communications with high-risk patients (Vest & Gamm, 2009; Hurley et al., 2008)