Professional caregivers must be educated in skin risk assessment and prevention no matter which healthcare setting they work in. We need to be able to teach patient caregivers about the necessity of pressure injury prevention and that their taking a proactive approach to skin care assessment can save many hardships in the future. When looking at risk factors—whether in the home, long-term care, or acute care—we have an important responsibility to educate and instruct patient caregivers on behaviors that prevent skin breakdown.

Pressure injuries are an enormous healthcare concern. Pressure injuries involve breakdown of the tissue from compression to the area, usually over a bony prominence and its outer surface. The effect of constant pressure results in ischemia (cell death, tissue necrosis). In long-term care facilities, 2.2% to 23.9% of patients develop pressure injuries (Schub et al., 2016).

With pressure injuries, the best prevention consists of diligent repositioning and off-loading. It is the constant pressure causing inadequate tissue perfusion to these areas that cause damage and breakdown, leading to a pressure injury. The patient’s comorbidities may come into account in pressure injury development if the patient is at an increased risk; thus, not all pressure injuries are avoidable, but quality patient care provides the best patient outcomes.

Assessment and Risk Factors

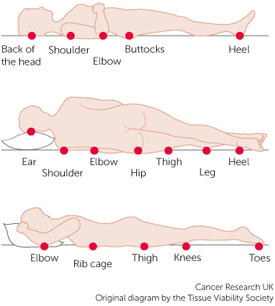

Pressure injuries are seen on pressure points on the body, mainly bony prominences. Providing the educational tools properly to assess patients at risk for skin breakdown is an asset to any healthcare team. The biggest risk factor for a patient’s developing a pressure injury is the inability to move and/or reposition. Bedbound and wheelchair bound patients have the greatest risk since they often do not have the ability or strength to reposition their weight off of the areas of pressure.

The Braden Score, developed in 1987 by Bergstrom and Braden, is an important and commonly used risk assessment tool for accurate assessment of skin breakdown. While the Braden Score is used more often in the acute care environment, it can be utilized in any clinical situation. Following the Braden Score, areas of risk include existing pressure injuries, fragile skin, pain to areas exposed to pressure, and extremities with impaired blood flow from vascular disease, smoking, or diabetes (Bergstrom et al., 1987).

When assessing a new patient, and with each ensuing visit, you need to review mobility status, cognition, activity level, moisture risk related to either incontinence or surface, nutritional intake, advanced age, comorbidities, and medications. Young patients can be at great risk for skin breakdown both in the home and the long-term setting based on a multiple of these factors. Constant evaluation of the environment and caregiver capabilities are beneficial in maintaining patient skin integrity. Instruct caregivers to inspect daily all areas that come into contact with a device (splint, oxygen tube, bedpan) for signs of breakdown.

Signs of breakdown can be new area of pink or redness, tenderness, temperature change, or a boggy feel. Your ability to engage and motivate prevention techniques by the caregiver impacts the patient’s overall health and future risk of breakdown. Empowerment of the caregiver is a key prevention strategy. With every visit, continue to motivate, educate, and reevaluate the patient and caregivers’ understanding of the risk factors and offer prevention techniques.

Prevention

Pressure injury prevention starts with the knowledge to identify areas at risk for pressure injuries and skin breakdown. See diagram below.

Pressure Injury Points

Source: Tissue Viability Society, 2017.

Identifying areas of pressure can easily be taught to all patient caregivers. The areas at greatest risk for pressure injury development are the sacrum and heels. Areas often overlooked include ankles, ears (from oxygen tubing), elbows, and between the knees on patients who keep their legs closely together in bed. The only skin issues that are staged are pressure injuries. Skin breakdown on non-pressure sites is not staged and is described as either partial or full thickness injuries. Prevention techniques that you can easily teach caregivers include reduction in shear, friction, and moisture and an increase in activity and mobility.

Repositioning and off-loading are vital in pressure injury prevention. Concentrate on off-loading to the sacrum and heels with pillows, wedges, or heel lift boots. If additional areas become affected from increased pressure be sure to instruct the caregiver on positioning the patient off of these areas as well. As a general rule for the caregiver, instruct to reposition the patient every two hours while in bed; this can be extended during caregiver nighttime sleep hours. Repositioning does not need to be an extreme change every time. Small adjustments, or boosting in bed, also assist in changing pressure locations. If it will assist the caregiver, make a turning schedule to help them remember when and how to position the patient throughout the day. This may seem like a small detail but it can reduce caregiver stress and encourage compliance.

When a patient is sitting in the chair, encourage reposition every hour. If the patients are able to reposition themselves while in the chair, encourage a shift in weight every 15 minutes. These weight shifts will offload the pressure and support proper circulation to pressure points, thus reducing skin breakdown.

Shear, Friction, and Moisture

Shear, friction and pressure all contribute to skin breakdown. Shear occurs when the skin remains in place and the underlying bony structures move against it and in the opposite direction, causing pressure to the bony prominences. It is an interaction of both gravity and friction against the skin. Areas of shear demonstrate a deep, undermining wound (Livingston, 2009).

Friction occurs when the skin slides against the linens or any other object/equipment causing skin breakdown. Look for areas of rough, red skin with superficial damage. Also, observe how the skin of the patient moves across a surface when repositioning or during transfers. Friction is due to mechanical force on the skin and can be present with shear. Prevention and treatment for areas of friction or shear include lowering the head of the bed to less than 30 degrees to prevent the patient from sliding against the sheets or added unnecessary pressure to pressure points.

Moisturize all bony prominences daily to assist with ease of moving across linens. Instruct caregivers on proper lifting, boosting and transferring patient to avoid dragging the body when repositioning. If the patient is able to utilize an overhead trapeze, request one from the physician to encourage patient involvement in repositioning and to assist the caregiver.

Moisture issues develop either from microclimate problems (too hot or cold in bed) or from incontinent episodes. Urine and/or fecal incontinence causes skin breakdown easily if the elements remain against the skin for a period of time. Moisture issues are not only uncomfortable and disturbing to the patient, but also lead to increased linen changes, laundry costs, purchasing of additional products, and caregiver time and stress (Beeckman et al., 2015). Se the Linen Management section for more information on moisture.

Activity and Mobility

One of the most important topics about which you can educate caregivers is patient mobility—encouraging caregivers to continually reposition and off-load all bony prominences. These are the biggest steps in prevention. If patients cannot move themselves, there will be constant pressure on the main prominences. If the caregiver is not moving the patient often enough, educate on the risk of skin breakdown, what it can lead to, and the benefits of repositioning.

Utilize physical therapy and occupational therapy to assist the patient and caregiver in range-of-motion (ROM) exercise and proper lifting and repositioning techniques to keep the caregivers safe. Physical therapy can work on safe transports, transition to bed and chair, out of bed, and standing to get to the bathroom. Mobility and activity combat constipation. Repositioning can lead to release of gas and stool, which will assist in patient comfort. Assess the home for ease of access to the bathroom and recommend accessories to help decrease fall risks.

Stretching and movement of the joints when repositioning is helpful to increase circulation and prevent stiffness. Encourage strengthening to reduce the risk of falls, decompensation, contraction, and stiffness. Balance, incontinence, falls, decreased strength, pressure injuries, and IAD may be inter-related and will all benefit greatly from the assistance and guidance of physical therapy and occupational therapy. Utilize these beneficial resources in caregiver and patient education.

Positioning Devices

There are many ways we can encourage patients and caregivers to assist in prevention. If you cannot get patients moving more—or at all—they need assistance. Selection of an appropriate pressure reduction surface is beneficial to both bedbound (mattress surface) and wheelchair (seat cushion) patients.

Medicare regulations have made it harder to supply patients with durable medical equipment than in the past. Prevention is not typically supported, and this is particularly true in bed support surfaces and cushions. Support surface selection must include certain elements of the patient’s overall status, such as mobility, conditions related to skin, lung function, weight, and level of independence (Beddoe & Mennella, 2016). Availability of durable medical equipment companies varies state by state; reimbursement has decreased, and many companies have closed as a result.

Discuss with a social worker or case manager the patient’s eligibility for certain pressure reduction surfaces. There will be times that support surface eligibility is out of your hands, but knowing when and how to order is beneficial. The benefits of certain support surfaces has a tremendous impact on how we can care for our patients, but eligibility factors that come into play can be a great struggle for all parties involved.

Pressure reduction surfaces are designed to redistribute body weight over the contact areas of the body. There are numerous mattresses, bed systems, and mattress overlays that are acknowledged to promote pressure redistribution. There are also support surfaces that are designed to provide the appropriate microclimate of patient skin temperature and moisture (eg, the Low-Air Loss Mattress).

Note: Become aware of the type and age of a positioning device in the patient home because there may be a better product available.

Types of Support Surfaces

Availability of support surfaces in the home vary greatly from what the patient may have utilized in the hospital. A hospital bed or mattress for the home requires a physician prescription. Guidelines categorize support surfaces as Groups 1 through 3. Group 3 provides the greatest level of support and redistribution. The following box explains the Medicare policy regarding pressure reducing support surfaces.

Categories of Support Surfaces

Group 1

Support surfaces are generally designed to either replace a standard hospital or home mattress or as an overlay placed on top of a standard hospital or home mattress. Products in this category include mattresses, pressure pads, and mattress overlays (foam, air, water, or gel).

Group 2

Support surfaces are generally designed to either replace a standard hospital or home mattress or as an overlay placed on top of a standard hospital or home mattress. Products in this category include powered air flotation beds, powered pressure reducing air mattresses, and non-powered advanced pressure reducing mattresses.

Group 3

Support surfaces are complete bed systems, known as air-fluidized beds, that use the circulation of filtered air through silicone beads. (These can be difficult to receive since the bed and frame are extremely heavy and require adequate structural support in the home).

Source: CMS, 2010. [https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/MedicareContracting/ContractorLearningResources/downloads/JA1014.pdf]

For patients who would benefit from a support surface, you must review guidelines for the level of skin breakdown. Just because a patient has skin breakdown does not mean they will qualify for a support surface. There must be a significant amount of skin breakdown for the patient to receive a support surface. The following box is a Medicare guideline for determining which support surface a patient is eligible for based on the degree of skin breakdown.

Medicare Coverage of Specific Groups of Support Surfaces

Group 1

Covered if the patient is completely immobile. Otherwise, patient must be partly immobile, or have any stage pressure ulcer and demonstrate one of the following conditions: impaired nutritional status, incontinence, altered sensory perception, or compromised circulatory status.

Group 2

Covered if the patient has a stage II pressure sore located on the trunk or pelvis, has been on a comprehensive pressure sore treatment program (which has included the use of an appropriate group 1 support surface for at least 1 month), and has sores that have worsened or remained the same over the past month. Also covered if the patient has large or multiple stage III or IV pressure sores on the trunk or pelvis, or if patient has had a recent myocutaneous flap or skin graft for a pressure sore on the trunk or pelvis and has been on a group 2 or 3 support surface.

Group 3

Covered if the patient has a stage III or stage IV pressure ulcer, is bedridden or chair-bound, would be institutionalized without the use of the group 3 support surface, the patient is under the close supervision of the patient’s treating physician, at least 1 month of conservative treatment has been administered (including the use of a group 2 support surface), a caregiver is available and willing to assist with patient care, and all other alternative equipment has been considered and ruled out.

Source: CMS, 2010. [https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/MedicareContracting/ContractorLearningResources/downloads/JA1014.pdf]

There will be times a patient may be eligible for a support surface but, based on their insurance situation or benefits available, it will be extremely difficult to receive the appropriate device. This is an upsetting situation for you to explain to the patient and/or caregiver. Unfortunately, in these situations you can only offer emotional support and encourage meticulous wound prevention and healing methods for the patient.

The most common support surface recommended by a home care agency for a wound care patient is from group 2. These surfaces include powered air flotation beds, powered pressure-reducing air mattresses, and non-powered advanced pressure-reducing mattresses. Since all support surfaces have different properties, you need to review the choices considering exclusion criteria and patient weight.

Always check whether patients “bottom out” on their current surface in chair or bed. Bottoming out refers to a situation wherein a patient has less than 1 inch between the surface and their body and thus is not getting adequate support from the surface. You can check for bottoming out by placing a hand under the support surface and feeling the amount of thickness of the surface to the patient. If there is not enough support, a new surface is needed.

Did You Know. . .

It is important the caregiver and patient understand that a support surface does not eliminate the need to regularly reposition the patient.

Proper positioning for patients with prolonged sitting time is equally as important as for those who are bedbound. The sacrum and heels become very vulnerable in patients who sit for long periods of time. If a patient spends time in a wheelchair, perform a sitting assessment to determine optimal seat height, width, and depth, as well as armrest and backrest height. Utilize physical therapy expertise with this; for example, a higher backrest is better for older adults and immobilized patients (Caple & Pravikoff, 2016).

Again, reinforce to reposition weight hourly if patients cannot move themselves, and encourage a regular 15-minute weight shift if patients are able to perform on their own. Approximately half of wheelchair users develop pressure injuries (Caple & Pravikoff, 2016).

Discuss skin assessment daily with patient and caregiver for early identification of skin breakdown or irritation. Work with physical therapy for strengthening exercises that support proper posture and mobility. Poor posture will cause abnormal redistribution of body weight that will increase tissue compression (Caple & Pravikoff, 2016). Note the type of chair cushion the patient has been using. A gel cushion is a great option if the patient currently is not using one. A gel cushion can be used on the patient’s favorite chair in the home and for their wheelchair.

A “donut” cushion is no longer an acceptable option and should be discarded. These cushions may off-load pressure to the middle of the sacrum and coccyx but they also increase pressure to other areas of the body, which can lead to breakdown on other parts of the skin. A gel cushion that is square in shape will best redistribute weight throughout the sacrum.

Linens

Linen usage impacts both patient care and financial issues—to the facilities or home. There is a common belief by caregivers that the more linens and padding under the patient the better. In fact, the more linens the more increase in the microclimate under the patient, and also the risk of inhibiting the effectiveness of the pressure redistribution mattress (Williamson & Sauser, 2009).

For bedbound patients, keep the head of bed no greater than 30 degrees (except when eating and drinking) to prevent sliding down in the bed and creating friction and shear. It can be helpful to place a pillow under the knees to assist in preventing sliding down in bed. Ensure there are no creases in the linens that can cause injury to the skin. Reinforce repositioning in bed every 2 hours during waking hours.

Avoid plastic incontinence pads that can increase heat and moisture to the skin. Manage sweating with cotton products and check the temperature of patients’ skin to feel if they are becoming too hot and moist.

The number of linens involved makes a big difference in whether the skin breaks down or remains intact. Too many linens and heat becomes an issue with moisture and, when too cold, there is a reduction in perfusion and not enough oxygen is available to the skin/wound site.

Avoid Too Many Linens!

When a proper support surface is utilized, too many linens will negate the effectiveness of the surface. However, the caregiver should ensure to pad between bony prominence and bed railings if the patient is positioned near the side.

Staging

The staging classification system from the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) reviews six categories of skin breakdown and recently added two new categories in 2016. Pressure injuries are the only wounds that are staged. It is also important to note that pressure injury staging is never reversed as the wounds go through the healing process. For example, a Stage 3 is not documented as a Stage 2 once it becomes shallower and smaller. It simply is documented as a “Healing Stage 3.”

Stage 1: Non-blanchable Redness

Stage 1 pressure injury develops as an area of non-blanchable redness to a pressure point. Our patient population has a variety of skin tones so you need to be aware of skin color changes on high-risk patients. When inspecting dark skin, moistening the skin assists in identifying changes in color. There are no open areas with a Stage 1 but the change in coloration is the beginning of skin breakdown and indicates the patient is at risk for further breakdown.

Stage 1 Pressure Wound

Source: Courtesy of S. Dean, Woundscope.

It is important to assess any new skin changes during each visit and to ask the family caregiver if they have noticed any changes since your last visit. New skin changes, especially non-blanchable redness, can be the first sign of increased pressure. Education to family caregivers on pressure points and proper off-loading will prevent deterioration to these patients. Instructions on positioning, off-loading, shoe choices, wheelchair, and bed cushions are all part of pressure injury prevention methods.

As we look to prevent breakdown, the beginnings signs of a Stage 1 pressure injury on a bony prominence can be prevented with turning, repositioning, off-loading, and investigation of any areas that show possible breakdown. These areas can present as soft, firm, painful, and warm or cool compared to the periwound.

The best treatment begins with encouraging prevention techniques. Reposition the patient off the pressure area at least every 2 hours. This can easily be done using pillows under the back or buttocks and floating the heels (keeping heel pressure off the bed or padding the foot rest of a wheelchair). Off-loading these pressure areas is an effective technique; moisturizing bony prominences to reduce shear and friction and prevent dry cracked skin is also an important step. When pressure is removed from the area, the redness will begin to reduce in appearance and size, and to heal.

Stage 2: Partial Thickness Wound

Stage 2 is a partial thickness wound over a pressure point that is superficial with no damage noted to the dermis. There is no slough or necrotic tissue and the wound bed is either red, pink, or pale. An area of pressure with a clear serum blister, either intact or ruptured, is also classified as a Stage 2. If the blister is intact, protect the area from further pressure or trauma to allow the area to begin healing. If the blister has ruptured, treat with the appropriate dressing to encourage a moist healing wound environment and continue providing off-loading and repositioning.

A patient can develop blisters on pressure points from footwear. Question the patient and caregiver about current footwear and inspect the shoes to see if there are areas that show worn marks or drainage that align with the injury to the feet. Sometimes the patient or caregiver is unaware it is the footwear causing the problem.

Stage 3: Full Thickness Wound, Shallow

Stage 3 Full Thickness Wound

Note: the marking on the skin indicates presence of undermining. Source: Copyright Medetec.co.uk.

Stage 3 is a full thickness wound in which slough or necrotic tissue may be present but do not obstruct the depth of visualizing the wound bed. There can be undermining or tunneling. While subcutaneous tissue may be visible, there is no muscle, bone, or tendon visible. The depth of a Stage 3 wound varies based on the anatomic location. For example, wounds of the nasal bridge, ear, occiput, or malleolus will be shallow due to a lack of subcutaneous tissue. On the other hand, areas with a great amount of adipose tissue (eg, sacrum, heels) can have great depth. Treat with off-loading and repositioning plus topical wound treatment, which will promote a moist wound-healing environment as well as adequate exudate management.

Stage 4: Full Thickness Wound, Deep

Stage 4 is also a full thickness wound; however, now muscle, bone, or tendon is visible. Assess for undermining and tunneling that may occur. Patients with Stage 4 pressure injuries require increased nutritional support; they also qualify for pressure reduction devices. Work with the caregivers in the home to review the patient’s plan of care and goals of wound healing.

An Unstageable pressure injury is one in which an area of yellow slough, or black soft or hard eschar, does not allow the base of the wound to be visualized; the depth of the wound cannot be determined, so it cannot be staged. If the plan of care is aggressive, it requires sharp debridement by a physician in the wound center or; or, if less aggressive, use of an enzymatic debriding agent—or allowing the body to do autolytic debriding. When the base of the wound is exposed, the area can then be appropriately staged.

A deep tissue injury (DTI) appears as an area of purple discoloration on a pressure point; an intact blood-filled blister on an area of pressure is described as a deep tissue injury. Appropriate off-loading and repositioning as necessary will hopefully allow the injured area of tissue to evolve into healthy tissue and begin to heal. A DTI may become less purple and begin to disperse in color. Educate the patient and caregiver to monitor the area to deter additional breakdown to occur and report any signs of further deterioration.

A DTI can appear up to 72 hours after the initial injury. Accurate assessment and history are key components of determining the start of the wound development. Question whether patients have fallen in the last several days and if they had remained on the ground or in the same position for several hours before someone was able to help them. If the patient has and remained on the ground for an extended period of time, deep tissue injuries may develop in different areas; for example, if a patient had fallen and was lying on the left side for many hours, you or the caregiver may notice that areas on the lateral knee, ankle, elbow, and hip all have purple areas indicating deep tissue injury.

After determining the patient sustained a fall and was on the ground, the wound etiology will be clearer and treatment options and education will be more accurate. It is important to determine the difference between a bruise and a deep tissue injury. Bruising to our skin goes through multiple color changes as it heals from yellows to purples, while a deep tissue injury will remain purple throughout the healing process and will only get a lighter color.

If the patient has recently been discharged from the hospital after surgery and has suddenly developed a deep tissue injury, discuss with the caregiver, physician, or acute care facility the length of operating room time and the positioning on the operating table. A surgery longer than 4 hours puts patients at increased risk of developing pressure injuries. With a DTI, it is necessary to reduce any continuous pressure to these areas. Moisturize all bony prominences daily to reduce shear and friction, reposition and pad or protect the area as needed. If the area remains under pressure the wound will evolve into greater tissue damage and could open, revealing more structures.

What is the stage of the following wound? (Blood-filled blister)

Answer: Deep tissue injury (DTI).

Staging a Deep Tissue Injury (DTI)

Stage 1 vs. DTI = red vs. purple

Clear blister vs. blood-filled blister = Stage 2 vs. DTI

A mucosal membrane pressure injury may not be seen much in the home care or long-term settings but you should be instructed on identification. These injuries result from tubing or a device resting on the mucosal membranes in the mouth. Since the anatomy of the mouth is different than the tissues of the skin, these injuries are not staged. Simply state the injury as a mucosal membrane pressure injury and document which part of the mouth has been damaged. Prevention and treatment include relocation of the tubing daily to help reduce pressure to the area of the mouth where it has been resting.

Medical device–related pressure injuries occur when any medical device has been applying pressure to the skin for a prolonged period of time and has injured the tissue. This can be from a Foley catheter, oxygen tubing, telemetry box, splint, brace, or any other object that applies continuous pressure to the skin. Many times these injuries do not occur on a pressure point on the body, rather developing from pressure from the device. This is a new category and is staged according to the depth of tissue damage. Accurate observations from the caregiver and attention to any device on the skin will easily prevent these injuries. Treatment includes removing the device from the area and selecting a wound healing product based on the level of tissue damage to promote healing.

Treatment

Patient history and wound etiology guide treatment choices. If the wounds have developed from prolonged sitting in a wheelchair, it is important to educate the caregiver and patient to reduce time in the wheelchair until the wound is healed. Patients may not want to remain longer in bed while the wound is healing, which makes wound healing education your top priority. If patients do not understand how the wounds will heal and the importance of off-loading pressure, they will not understand the reason for the instructions.

With all wounds, a moist wound healing environment is necessary, along with the off-loading of pressure to the injured tissue. Patients need to know that a wound heals from the bottom up and recognize factors that delay the healing. When a wound has depth, the area must be gently packed to encourage growth from the bottom skin layers and prevent premature closure of the roof of the wound.

Present the reason for keeping the wound open and healing from the bottom to prevent making an incubator for more infection. When the top layer of skin closes before the wound bed has adequate time to heal, the open space left beneath the top skin layer will act as an incubator for a possibility of a new infection. Wound packing is a difficult task for many caregivers and product selection must be based on the ability of the caregiver and the number of times per week the wound will need to be changed.

Treatment options are discussed with the patient’s primary care physician; however, physicians not skilled in wound care often rely on the knowledge of the nursing team for an appropriate recommendation. When determining best treatment methods in home care, long-term care and assisted living, the first thing to review is the assistance the patient will have with dressing changes. If the physician wants a daily dressing change but you are aware this would be impossible, based on the support system and patient capabilities, discuss this with the physician so a different product can be utilized.

Treatment selection should focus on providing a moist wound healing environment, adequate exudate management, and comfort to ensure compliance and ease of patient use both physically and financially. There will be instances when a physician prescribes wound dressings that cannot be managed by the patient either from physical difficulties or financial difficulties. Here again, you need to bring this to the physician’s attention and offer alternatives.

Numerous products are available for the long-term and home care environment that will promote wound healing without the need for daily changes. Many of the current products have the capability to remain in place for up to 7 days, provided the drainage is controlled. Your greatest contribution as a clinician is to understand how the products are designed to be used.

Product formulary will vary based on the facility and agency of the clinician, but a basic understanding of product usage is advantageous for the clinician and their patient. For example, many foam dressings can remain in place for 3 to 5 days and some up to 7 days, depending on the amount of drainage. An alginate dressing is designed to stay in place for 48 hours, and changing the dressing more often is a waste of product, time, and money. Having basic product knowledge can save both patient and agency time and money as well as added stress.

Many laypeople feel the need to visualize the wound daily or to “keep it open to air” to let it heal. These are old methods that will not promote rapid wound healing. It has been proven through research that our skin cells heal more quickly in a moist environment. Explain to the patient and family that, from years of research, we have learned that our skin cells will “swim together faster than they can run,” which is why we now keep the wound covered and encourage moisture in the wound bed.

Case: Amy

Amy, an 84-year-old female, who ambulates with walker on occasion, usually sits at home in her chair most of the day watching television. She can use the commode independently but also wears incontinent diapers because she has several accidents throughout the day. Her nutrition is questionable based on body weight of 110 lbs and 5 feet 6 inches tall. She is alert and oriented x 2, pleasantly forgetful, and lives with her spouse who is also 84 years old and cares for her as best he can.

She has developed a pressure injury to her left hip. The wound size is approximately 8 cm x 4 cm. Wound bed with 50% black eschar, 40% yellow and 10% pink, slight odor, periwound pale attached, rolled edges, and Amy complains of tenderness to the area but has difficulty to fully assess due to mild forgetfulness. The wound has a small amount of serous/purulent drainage and her husband has been using a large ABD pad to “protect” the area. The patient has no allergies and, surprisingly, does not have any other comorbidities besides macular degeneration and dementia.

Wound Showing Black Eschar

Source: T. Sbriscia.

What is the stage of the wound at right? Should any referral be made? What are the first steps in treatment? What assessment should be made in the living environment and what products should you recommend?

The wound is unstageable, based on the degree of black eschar and that we cannot visualize an accurate wound depth. The clinician can use a cotton swab to palpate the wound bed to determine if the area of black eschar is loose or if there are any pockets or tunneling. This patient definitely needs a referral to a wound center physician as soon as possible to reduce the risk of infection and to remove all devitalized tissue.

The first steps in the home are to assess for signs of infection based upon the purulent drainage and the appearance of the wound. Question the patient and caregiver regarding fever, chills, increased drainage, when the odor was first noticed, and, of course, how long the wound has been present.

Assess the patient’s favorite chair and see if it is possible to determine where the pressure is coming from. It could be the chair or it could also be that the patient always sleeps on her left side. Review the support surfaces of the bed and chair. Discuss with the patient and spouse how the wound most likely started and begin educating on how to reduce pressure to the hip and what adjustments need to be made.

Since the patient is forgetful, assess the ability of the caregiver and write down simple and detailed instructions to help guide him with the treatment process. The patient will most likely need sharp debridement to remove the dead tissue in the wound bed. Review the patient’s nutritional status to support wound healing and encourage supplements if appropriate. Lab work can be prescribed by the wound center for albumin, pre-albumin, and total protein. Chances are the patient was started on an oral antibiotic and the wound was cultured at the wound center. Based on the outcome of the wound care center and the amount of debridement performed by the physician, a topical enzymatic debriding agent can be used daily if there is devitalized tissue remaining in the wound bed.

The patient has assistance from her spouse at home for daily dressing changes, so this will begin as the best treatment option. Observe the spouse performing wound care and instruct as needed. This wound may have depth post debridement. Ensure that the caregiver is willing to gently pack the wound and choice a secondary dressing that provides adequate moisture control based on the amount of wound drainage.

Amy will continue with weekly visits to the wound center to monitor the wound progression and the clinician can also recommend physical therapy to assist in strength training that will help her to reposition herself in her chair and in bed.

Investigate the cause of her occasional incontinent episodes. Since the patient is on very little medication, the cause could be functional and the patient is forgetting to use the bathroom throughout the day. Discuss a timed voiding program with the spouse, encouraging him to remind Amy to use the bathroom every 2 to 3 hours to help reduce accidents.

Monitor Amy’s food intake and hydration and offer suggestions as needed in protein and water consumption. Provide and reinforce wound prevention techniques for the caregiver and encourage him to report any skin changes to you as soon as possible to help reduce re-injury or the formation of a new injury.

Additional Treatment Options

There are products to encourage a moist wound healing environment and there are products that support wound debridement, and some will do both. Products that encourage debridement, when necessary, are an added benefit for the patient. The body has an amazing ability to heal itself provided it receives help from its host.

When assessing a wound for appropriate product selection, determine if there will be debridement, and what type will be most beneficial. In autolytic debridement, the body uses its own enzymes to liquefy necrotic tissue. A dressing can be used to cover the wound and allow the cells in the body to liquefy the necrotic tissue and essentially dispose of the dead tissue, allowing the new tissue to begin to form. Dressings that assist in autolytic debridement typically remain in place for 3 to 7 days depending on the product and manufacturer guidelines. For healthy people, this occurs naturally in all wounds.

In patients with various comorbidities and conditions that affect the immune status, this will not occur as easily. Enzymatic debridement (utilized in the Amy’s case study) is a chemical debridement where enzymes are introduced to the wound bed allowing the dead necrotic tissue to be broken down and the wound bed cleansed. This agent is applied topically and daily and works faster to eliminate necrotic tissue than autolytic debridement.

Sharp debridement is done by a physician or qualified nurse practitioner. The practitioner can use a blade, scissor, or curette to remove necrotic tissue selectively. This method is fast and efficient and usually requires pain medication or topical analgesia. An unstageable wound with large amounts of yellow or black necrotic tissue will benefit greatly from sharp debridement because it could take topical products too much time to penetrate and debride a large amount of tissue.

The longer a wound remains open, the greater the risk of infection. A wound with necrotic tissue poses a likely source of infection to the patient. Educate caregivers on identifying necrotic tissue and to alert you of any changes between visits. Sharp debridement can be done at the bedside in the acute care setting, but most often will be done at a wound center on a weekly basis to remove necrotic tissue and encourage new tissue growth.

Finally, mechanical debridement is done manually by either removing a dry dressing that has become attached to the wound bed or with forceful irrigation to the wound bed. This is a non-selective technique that can remove both healthy and unhealthy tissue and can be painful for the patient. This type of debridement is best for wounds that have only a moderate amount of necrotic debris.

* * *

Treatment options and choices vary with each individual patient. Provide a thorough assessment, ask many questions of the patient and caregiver and collaborate with other healthcare providers to ensure the best plan of care for each patient. Treatment options can change during the healing process and reassessment must be ongoing. Educate the patient and caregiver during the treatment and healing process and provide a supportive environment.