Dementia is a syndrome, a collection or grouping of symptoms—the result of progressive deterioration and loss of brain cells and brain mass. Different types of dementia affect different parts of the brain. Some dementias start in a part of the brain that controls a specific function such as short-term memory or emotion. Other dementias affect the entire brain—or more than one part of the brain—causing other symptoms.

Dementia occurs primarily in later adulthood and is a major cause of disability in older adults. Although almost everyone with dementia is elderly, dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

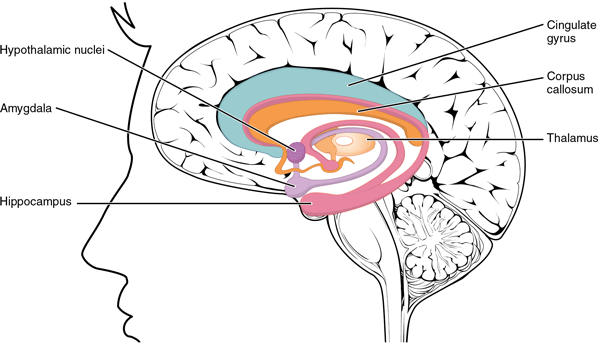

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, responsible for 60% to 80% of all cases. It typically starts in an area of the brain called the hippocampus—the part of the brain responsible for new, short-term memories. The hippocampus is part of the brain’s limbic system.

The Limbic System

Structures arranged around the edge of the cerebrum constitute the limbic lobe, which includes the amygdala, hippocampus, and cingulate gyrus, and connects to the hypothalamus. Source: OpenStax and Rice University. Creative Commons Attribution License v4.0.

Damage to the hippocampus causes a person with dementia, particularly someone with Alzheimer’s disease, to forget something that happened just a moment ago. Although most types of dementia start in one part of the brain, eventually the entire brain will be affected.

How the Brain Works

The brain is the most complex organ in the body—a sophisticated communications center containing billions of nerve cells (neurons). This three-pound mass of gray and white matter is at the center of all human activity. We need it to drive a car, to eat a meal, to breathe, to create an artistic masterpiece, and to enjoy everyday activities. The brain regulates the body’s basic functions; it enables us to interpret and respond to everything we experience and shapes our thoughts, emotions, and behavior (NIDA 2020, July).

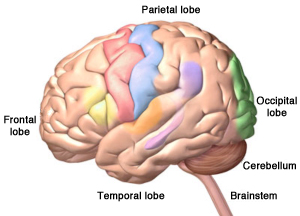

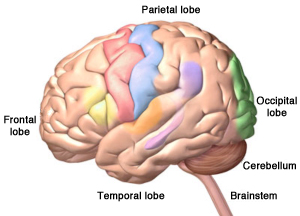

The Human Brain

The four lobes of the cerebrum, plus the cerebellum and the brainstem. Alzheimer’s disease starts in hippocampus, located in the temporal lobe. Copyright, Zygote Media Group, Inc. Used with permission.

Within the brain, vast networks of nerve cells pass messages back and forth among different structures within the brain, the spinal cord, and the nerves of the rest of the body (the peripheral nervous system). These nerve networks coordinate and regulate everything we feel, think, and do (NIDA 2020, July). Dementia interrupts the efficient function of these networks, affecting every aspect of a person’s life.

Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia damage a critically important part of the brain called the cerebrum. The cerebrum is divided into 2 hemispheres, each containing four of lobes.

The cerebrum allows us to think, form memories, communicate, make decisions, plan for the future, and act morally and ethically. It also controls our emotions, helps us make decisions, and helps us tell right from wrong. The cerebrum also controls our movements, vision, and hearing.

Although the nerve cells of each lobe communicate extensively with nerve cells in other lobes, specific areas of each lobe are responsible for certain functions.

- Frontal lobes: reasoning, judgement, motor control, planning, decision-making

- Temporal lobes: memory and emotion, hearing, language

- Parietal lobes: sensation, touch, temperature, pressure, pain

- Occipital lobes: visual processing, depth, distance, location of objects

When dementia strikes, brain cells in the cerebrum begin to shrink and die. As the damage progresses, brain cells are no longer able to communicate effectively with one another. Not surprisingly, as more and more brain cells are damaged, connections are lost, pathways are disrupted, and eventually people with dementia lose many brain functions.

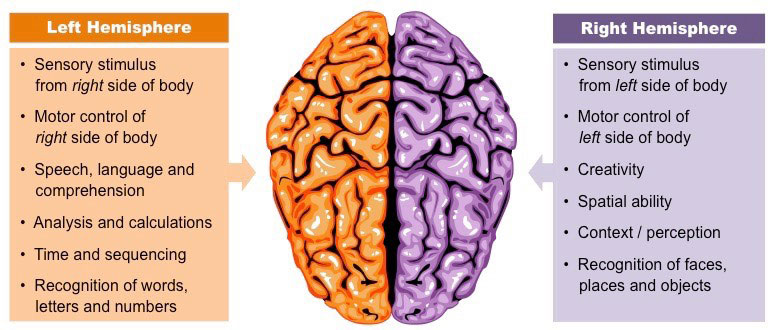

The right and left sides or hemispheres of the cerebrum differ in function. For example, in the front part of the brain, damage in the left frontal and left temporal lobes can affect the brain’s language centers, causing difficulties with speech and language. Damage to the right side of the brain can cause problems with spatial awareness and the ability to identify objects by touch.

The parietal lobes—behind the frontal and temporal lobes—provide another example of the differences between the right and left sides of this part of the brain. Several portions of the parietal lobe are important to language and visuospatial processing; the left parietal lobe is involved in symbolic functions in language and mathematics, while the right parietal lobe is specialized to process images and interpretation of maps (i.e., spatial relationships) (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

The Hemispheres of the Brain

Source: Cornell, B. 2016. BioNinja. Reprinted by permission.

It is important not to exaggerate the differences between the functions of the left and right hemispheres; both hemispheres are involved with most processes. Additionally, neuroplasticity (the ability of a brain to adapt to experience) enables the brain to compensate for damage to one hemisphere by taking on extra functions in the other half, especially in young brains (Lumen Learning, n.d.).

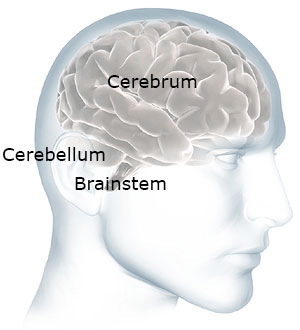

The Three Main Sections of the Human Brain

The cerebellum and brainstem are at the back of your head below the cerebrum. Source: NIH. Used with permission.

The human brain has two other important parts: the cerebellum and the brainstem. Touch the back part of your head just below the occipital lobes. The cerebellum is right there. It is involved with coordination and balance.

Now move your hand a little down and stop before your get to your spine. The brainstem is right there—at the back of the head, above your spine. It connects the brain to the spinal cord. The brainstem oversees automatic functions such as breathing, digestion, heart rate, and blood pressure. Although it is possible for the brainstem and cerebellum to be damaged by stroke or traumatic injury, they are generally not affected by dementia.

How Dementia Affects the Brain

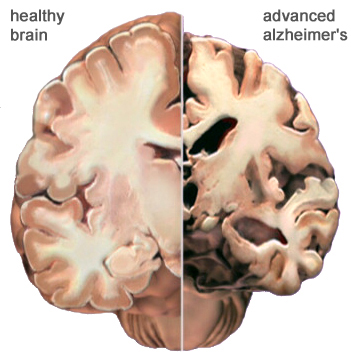

Normal Brain Contrasted with AD Brain

A view of how Alzheimer’s disease changes the whole brain. Left side: normal brain; right side, a brain damaged by advanced AD. Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

Dementia changes the entire brain. In Alzheimer’s disease, nerve cells in the brain die and are replaced by abnormal proteins called plaques and tangles. As the nerve cells die, the brain gets smaller. Over time, the brain shrinks, affecting nearly all its functions.

Alzheimer’s disease usually affects memory and emotional control before other symptoms are obvious. Other types of dementia, because damage is to another part of the brain, will have different symptoms. Although dementia can start in one part of the brain, eventually it will affect the entire brain.

Normal Age-Related Changes and Memory Loss from Dementia

We all experience physical and mental changes as we age. Some people become forgetful when they get older. They may forget where they left their keys. They may also take longer to do certain mental tasks. They may not think as quickly as they did when they were younger. These are called age-related changes. These changes are normal—they are not dementia.

Age-related changes don’t affect a person’s life very much. Someone with age-related changes can easily do everything in their daily lives—they can prepare their own meals, drive safely, go shopping, and use a computer. They understand when they are in danger and continue to have good judgment. They know how to take care of themselves. Even though they might not think or move as fast as when they were young, their thinking is normal—they do not have dementia.

The table below describes some of the differences between someone who is aging normally and someone who has dementia.

Normal Aging vs. ADRD | |

|---|---|

Normal aging | AD or other types of dementia |

Occasionally loses keys | Cannot remember what a key does |

May not remember names of people they meet | Cannot remember names of spouse and children—don’t remember meeting new people |

May get lost driving in a new city | Get lost in own home, forget where they live |

Can use logic (for example, if it is dark outside it is nighttime) | Is not logical (if it is dark outside it could be morning or evening) |

Dresses, bathes, feeds self | Cannot remember how to fasten a button, operate appliances, or cook meals |

Participates in community activities such as driving, shopping, exercising, and traveling | Cannot independently participate in community activities, shop, or drive |

In some older adults, memory problems are a little bit worse than normal age-related changes. When this happens, the person has mild cognitive impairment, also called MCI.

Mild cognitive impairment isn’t dementia, although a large percentage of people with MCI experience personality changes. They may have a little more difficulty than is normal with thinking and memory. For some people, mild cognitive impairment gets worse and develops into dementia, but this doesn’t happen with everyone.

Other Neurologic Diseases or Conditions That Can Cause Dementia

Symptoms are a little different in each type of dementia. It is good to know the difference to help you understand why someone is acting the way they are. Characteristics of the various types of Alzheimer’s dementia and accompanying symptoms are described next.

Frontal-Temporal Dementia

Look at the picture of the brain below. Put your hand on your forehead. The part of your brain just behind your forehead is called the frontal lobe. Now slide your fingers from the front to the side of your head (your temple). This part of the brain is called the temporal lobe.

There is a type of dementia that affects this part of the brain. It is called frontal-temporal dementia. It is thought to be the most common type of dementia in people under the age of 60 and is responsible for 5-10% of all cases of dementia. It’s not nearly as common as Alzheimer’s and usually starts at a much younger age.

Brain Showing Frontotemporal Lobes

Damage to the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes causes forms of dementia called frontotemporal disorders. Copyright, Zygote Media Group, Inc. Used with permission.

We use the front part of our brain to make decisions, to tell right from wrong, to control our emotions, and to plan for the future. Someone with dementia in this part of the brain will have poor judgment and lose the ability to tell right from wrong. They also have less control over their behavior.

Instead of losing short-term memory like people with Alzheimer’s disease, a person with frontal-temporal (or frontotemporal) dementia might start doing things that are confusing to their friends and family. They might steal, even though they have never stolen in the past. They might make inappropriate sexual remarks or engage in inappropriate sexual behaviors, even though they have never done these things in the past.

Frontotemporal dementia is usually categorized under three subtypes:

- Behavior variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD): changes in personality and behavior that can affect people in their early 50s and 60s. Affects judgement, empathy, foresight, and planning.

- Primary progressive aphasia (PPA): usually begins before the age of 65. Affects language skills, reading, writing, and comprehension.

- Disturbances of motor function, muscle weakness or wasting, without behavioral or language problems. (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021a)

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia is a general term used to describe changes in cognition resulting from impaired blood flow to the brain. It can be caused by a stroke or a series of small strokes or any condition that causes brain damage or reduces blood flow to the brain. Factors that increase the risk of heart disease such as diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking also increase the risk of developing vascular dementia. You might have cared for more than one client with vascular dementia because many older adults have high blood pressure that isn’t under good control.

Vascular dementia is responsible for 20% to 30% of all cases of dementia. Generally, vascular dementia doesn’t affect memory as much (or in the same way) as Alzheimer’s, at least in its early stage. Symptoms are related to the part of the brain experiencing reduced blood flow.

Vascular dementia can cause mood changes that are stronger than the mood changes you might see in someone with Alzheimer’s. It can also affect judgment—but not as strongly as in someone with frontal-temporal dementia. It can be difficult to differentiate vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia because they can occur together. Cognitive changes can be gradual or occur in noticeable steps downward from a person’s previous level of function.

Lewy Body Dementia (LBD)

Lewy body dementia is a spectrum of disorders rather than a single diagnosis. LBD is less common than Alzheimer’s dementia, but more common than frontal-temporal and vascular dementia.

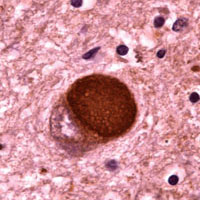

There are two types of LBD: dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia, which share a common etiology. Symptoms are caused by the build-up of Lewy bodies—accumulated bits of alpha-synuclein protein—inside the nuclei of neurons in areas of the brain that control certain aspects of memory and motor control. These unwanted molecules (Lewy bodies) can become scattered throughout the brain. Symptoms can include:

- Disturbances of movement (slowness of movement, rigidity, shuffling gait, tremors, difficulties with balance)

- Cognition decline (fluctuations in concentration, alertness, and attention)

- Behavioral changes (mood fluctuation, depression, anxiety, apathy, hallucinations, delusions)

- Sleep disturbances (daytime sleepiness, restless leg syndrome, difficulties awakening, acting out dreams, falling out of bed)

- Autonomic dysfunction (constipation, urinary incontinence, sexual dysfunction, difficulty regulating blood pressure and temperature, low blood pressure)

Lewy Body

Microscopic image of a Lewy body. Courtesy of Carol F. Lippa, MD, Drexel University College of Medicine. Source: Alzheimer’s Disease Information and Referral Center. Public domain.

In Parkinson’s disease dementia, movement deficits are the first symptoms to appear. This can include festinating gait (shuffling), balance problems, muscle rigidity, resting tremors, bradykinesia (slow movement), and loss of facial expressiveness.

In general, memory is less affected than in Alzheimer’s disease, at least at first. But hallucinations, visuospatial changes, fluctuation in cognitive abilities, and sudden confusion can be present. These symptoms can come and go throughout the day.

Dementia Characteristics and Symptoms | |

|---|---|

Type of dementia | Characteristics and symptoms |

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) 60-80% of cases |

|

Frontal-temporal dementia 5% to 10% of cases, prevalence thought to be underestimated |

|

Vascular dementia 20% to 30% of cases |

|

Dementia with Lewy bodies About 5% to 10% of cases |

|

Conditions That May Mimic Alzheimer’s

Conditions other than dementia can affect cognition, causing dementia-like symptoms; some of these conditions are reversible with appropriate treatment (NINDS 2020, March 3):

- Side effects of medications or medication interactions

- Metabolic and endocrine abnormalities

- Vasculitis (inflammation of brain blood vessels)

- Nutritional deficiencies, especially of vitamin B1 (thiamine)

- Some chronic infections around the brain

- Constipation

- Subdural hematomas

- Poisoning from exposure to lead, heavy metals, or other poisonous substances

- Alcohol, prescription medications, and recreational drugs

- Brain tumors, space-occupying lesions, and hydrocephalus

- Hypoxia or anoxia (not enough oxygen)

- Autoimmune cognitive syndromes

- Sleep apnea

Delirium and depression can also affect cognition and are particularly prevalent and often overlooked or misunderstood in older adults. Both conditions can be superimposed on dementia, particularly in older hospitalized patients.

Delirium

Delirium characteristically has an acute onset, fluctuating course, and the presence of an underlying medical condition, medication or psychoactive substance, or medication/substance withdrawal. Patients with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia can also have superimposed delirium as a cause for an abrupt worsening of their usual symptoms. History is the key to differentiating behavioral and psychological symptoms from delirium: in delirium, the onset of symptoms occurs over days to 1 to 2 weeks, while in behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, symptoms gradually worsen over several weeks to months (Cloak & Khalili, 2020).

Patients with delirium frequently have changes in the level of consciousness, such as periods of somnolence or extended periods of wakefulness, which are typically less prominent in behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Visual hallucinations may be prominent in delirium, whereas delusions are more common in patients with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. It can be challenging to distinguish Lewy body dementia from delirium, since patients with Lewy body may have visual hallucinations and fluctuations in the level of consciousness, but these symptoms will have a more gradual onset than in patients with delirium (Cloak & Khalili, 2020).

Patients with suspected delirium should have a thorough medical evaluation, beginning with history and physical and followed by targeted laboratory testing and imaging based on these findings: typically, comprehensive metabolic panel, CBC, urinalysis, cardiac enzymes, chest X-ray, and toxicology screens are performed routinely, with neuroimaging, lumbar puncture, blood gases, and EEG reserved for select cases. Unlike behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, symptoms related to delirium will resolve, albeit sometimes gradually, once the underlying cause is corrected (Cloak & Khalili, 2020).

The most common causes of delirium are related to medication side effects, hypo or hyperglycemia (too much or too little blood sugar), fecal impactions, urinary retention, electrolyte disorders and dehydration, infection, stress, metabolic changes, an unfamiliar environment, injury, or severe pain.

Depression

Depression is a disorder of mood involving a disturbance of emotions or feelings. The diagnosis of depression depends on the presence of two cardinal symptoms: (1) persistent and pervasive low mood, and (2) loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities. Depressive symptoms are clinically significant when they interfere with normal activities and persist for at least two weeks, in which case a diagnosis of a depressive illness or disorder may be made (Diamond, 2015).

A man depressed about the loss of his spouse. Source: NIA/NIH.

Depression has been suggested as a risk factor for dementia. According to recent studies, late-life depression is associated with increased dementia risk. Some researchers have proposed indirect evidence that the effect of depression on dementia risk is altered by comorbid cerebrovascular disease, which is typically characterized by cerebral ischemia and hemorrhage (Jang et al., 2021).

In a recent study, depression was found to have an exceptionally significant effect on dementia in individuals who have had a stroke. Risk factors for dementia in patients with cerebrovascular disease also includes depressive illness (Jang et al., 2021). Along with apathy, depression is one of the most common mood disorders in Alzheimer’s disease (Nowrangi et al., 2015).

Because of these complexities, diagnosing depression in patients with dementia can be difficult. Denial and cognitive impairment may compromise self‐report of depressive symptoms. As a person’s dementia progresses, the presentation of depression may alter, with non‐verbal behaviors such as demanding behavior and clinging being more apparent than cognitive features. Moreover, autonomic symptoms such as poor concentration and anhedonia* are features of both depression and dementia (Dudas et al., 2018).

*Anhedonia: a reduction in, or complete lack of ability, to enjoy activities the person usually finds enjoyable.

Although depression can be hard to recognize in people with dementia, there is evidence that it is common and associated with increased disability, poorer quality of life, and shorter life expectancy. Many people with dementia are prescribed antidepressants to treat depression, but it is uncertain how effective they are (Dudas et al., 2018).

Depression in older adults has been linked to dementia, although it is unclear whether it is a risk factor for dementia, or a prodromal symptom.* In some cases, depression and dementia may be caused by common risk factors such as cerebrovascular disease. In others, they may not have a connection at all and simply occur together by chance—as two separate neuropsychiatric diseases. Among depressed older adults, it is difficult to assess who may be at increased risk for developing dementia and, by extension, who would benefit from specific interventions to decrease this risk (Wiels et al., 2020).

Prodromal symptom: a term used to describe a group of symptoms that may precede the onset of a mental illness. It is not a diagnosis.

Although depression is frequently present in those with Alzheimer’s disease, it is much more common in people with Lewy Body dementia. Depressive symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies are associated with a greater cognitive decline and, in Alzheimer’s disease, significantly relate to lower survival rates over a 3-year period (Vermeiren et al., 2015).

Diagnostic Guidelines

Diagnosis of AD is most often based on a combination of medical history and detailed physical, neurologic, and neuropsychological exams. Brain imaging can be used, but preclinical dementia is difficult to diagnose accurately in early days using these methods. In recent years, a number of soluble components in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood have been identified as potential, useful biomarkers* for AD (DeMarshall et al., 2019).

*Biomarkers: A measurable substance that may indicate the presence of a particular biological state, a clinical disease, an environmental exposure, or disease susceptibility.

Measuring biomarkers for brain diseases in blood is the focus of intense research although there are a number of challenges. Because of the blood-brain barrier, biomarkers are generally present at relatively low concentrations in blood taken from the brain. In addition, some biomarkers related to AD pathology are expressed in non-cerebral tissues, which may confound their measurement in the blood. Blood may also contain antibodies, which can give falsely high or low results. This is less of a problem in CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) because antibody levels in CSF are much lower. Finally, the biomarker of interest may be degraded by various substances in blood plasma (Zetterberg & Burnham, 2019).

Recently, a blood test has been developed that measures a specific variant of tau protein in an ordinary blood plasma sample. The test measures the presence of the P-tau181 variant, using a method called Single Molecule Array. P-tau181 has long been measured in CSF and is seen in advanced positron emission tomography (PET) scans. But both of these methods are expensive and not universally available and therefore not practical in primary care settings (University of Gothenburg, 2020).

There is potential to use this blood test to identify Alzheimer’s in its early stage when cognitive impairment is mild. This may provide primary care practitioners with the ability to evaluate and treat people early in the disease rather than when symptoms are so obvious that they show up during cognitive testing.

Symptoms are a little different in each type of dementia. It is good to know the difference to understand why someone is acting the way they are.

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is based on symptoms; there is no test or technique that can diagnose dementia. To guide clinicians, in 2011 the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) published updated diagnostic guidelines, which are intended to provide a deeper understanding Alzheimer’s disease than earlier guidelines. The 2011 guidelines:

- Recognize that Alzheimer’s disease progresses on a spectrum with three stages: (1) an early, preclinical stage with no symptoms; (2) a middle stage of mild cognitive impairment; and (3) a final stage marked by symptoms of dementia. Cognitive decline is gradual and progressive.

- Expand the criteria for Alzheimer’s dementia beyond memory loss as the first or only major symptom and recognize that other aspects of cognition, such as word-finding ability or judgment, may become impaired first. Other cognitive changes can include changes in:

- Episodic memory

- Executive functioning

- Visuospatial abilities

- Language functions

- Personality and/or behavior

- Reflect a better understanding of the distinctions and associations between Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s dementias, as well as between Alzheimer’s and disorders that may influence its development, such as vascular disease, delirium, or stroke.

- Recognize the potential use of biomarkers—indicators of underlying brain disease—to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. However, the guidelines state that biomarkers are almost exclusively to be used in research rather than in a clinical setting (NIA, 2020).

Since the publication of the 2011 guidelines, researchers have increasingly come to understand that cognitive decline in AD occurs continuously over a long period, and that progression of biomarker measures* is also a continuous process that begins before symptoms are evident. The disease is now regarded as a continuum rather than three distinct clinically defined stages (Jack et al., 2018).

*β amyloid deposition, pathologic tau, and neurodegeneration/neuronal injury.

A 2018 update of the 2011 NIA-AA diagnostic guidelines added a “numerical clinical staging scheme.” This staging scheme reflects the sequential evolution of AD from an initial stage characterized by the appearance of abnormal biomarkers in asymptomatic individuals. As biomarker abnormalities progress, the earliest subtle symptoms become detectable. Further progression of biomarker abnormalities is accompanied by progressive worsening of cognitive symptoms, culminating in dementia (Jack et al., 2018).

The numerical clinical staging scheme is as follows:

- Performance within expected range on objective cognitive tests.

- Normal performance within expected range on objective cognitive tests. (Transitional cognitive decline: Decline in previous level of cognitive function, which may involve any cognitive domains.)

- Performance in the impaired/abnormal range on objective cognitive tests.

- Mild dementia.

- Moderate dementia.

- Severe dementia. (Jack et al., 2018)

In 2018 an Alzheimer’s Association workgroup lead by Alireza Atri published a report describing the need for clinical practice guidelines for use in primary and specialty care settings. The guidelines build on the NIA-AA guidelines but add a clinical component for the evaluation of cognitive impairment thought to be related to Alzheimer’s disease or a related type of dementia.

Key components include:

- All middle-aged or older individuals who self-report or whose care partner or clinician report cognitive, behavioral, or functional changes should undergo a timely evaluation.

- Concerns should not be dismissed as “normal aging” without a proper assessment.

- Evaluation should involve not only the patient and clinician but, almost always, also involve a care partner (e.g., family member or confidant). (Atri, 2018)

Causes, Cures, and Research Overview

The past decade has been marked by frustrating therapeutic failures that have led some to question the amyloid hypothesis as a central feature of Alzheimer’s disease. The emergence of tau-related therapies, developments in biomarkers (including brain imaging and CSF- and blood-based markers) has increased awareness of the importance of neuroinflammation (Galasko & Scheltens, 2020).

A biomarker-based classification of Alzheimer’s that enables detection and supports intervention before the development of cognitive decline is receiving extensive investigation. Digital biomarkers including passive sensors, wearables, and device-based testing are increasingly being studied and deployed. Neuropathological and biomarker studies are demonstrating that multiple pathologies contribute to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline (Galasko & Scheltens, 2020).

Extrinsic factors* that may contribute to brain development, resilience, reserve, and vulnerability are being widely studied. Efforts to understand Alzheimer’s and related disorders from a genetic and molecular standpoint are rapidly growing. This has led to renewed attention to preclinical models of disease, from cell-based models to animal models (Galasko & Scheltens, 2020).

*Extrinsic factors: things acting from the outside of a person such as nutrition, environment, smoking/diet, alcohol use, exercise, clutter, assistive devices, footwear, etc.

New methods of protein analysis, including cryo-electron microscopy, are providing insights into the structure of proteins, including aggregated proteins* emblematic of Alzheimer’s and related disorders. Drug discovery and translation now include small molecules, immunologic therapies, and biological approaches, as well as efforts to investigate the impacts and biology of lifestyle interventions (Galasko & Scheltens, 2020).

*Aggregated proteins: a biological phenomenon in which damaged or mis-folded proteins collect either inside or outside a cell. This is associated with many neurodegenerative diseases.

Although there is currently no “cure” for Alzheimer’s disease, the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention and Care Report suggests that, if nine potentially reversible risk factors are considered, up to a third of the dementia cases might be preventable. While prevention is always better than cure, this is particularly important in the field of dementia as it takes years for the Alzheimer’s pathology to accumulate and current interventions are not able to modify the disease once pathology is present (Montero-Odassoet et al., 2020).

The Lancet Commission on Dementia noted a reduction of age-related incidence of dementia in several high-income countries, among those with more education or wealth. This suggests that it is possible to delay or prevent dementia. It concluded that up to 35% of dementia could be prevented by modifying nine risk factors:

- Low education

- Midlife hearing loss

- Obesity

- Hypertension

- Late-life depression

- Smoking

- Physical inactivity

- Diabetes

- Social isolation

An important aspect of this life course conceptual framework is that modifications of risk factors can be done by lifestyle interventions, which can influence dementia decades before clinical onset (Montero-Odassoet et al., 2020).