A characteristic is a feature or quality you would typically expect to see in a disease. Each type of dementia has its own set of characteristics. For example, one characteristic of frontal-temporal dementia is that it typically starts at an earlier age than Alzheimer’s.

A man in the early stage of memory loss. Source: NIA/NIH, public domain.

One of the first characteristics noticeable in someone with Alzheimer’s disease is that they have trouble making new memories. This is called short-term memory loss. This happens because the part of the brain that forms new memories (the hippocampus) is damaged by dementia. Usually, long-ago memories are still intact—this is because the areas of the brain that store long-term memories are not as affected in the early stage of Alzheimer’s dementia. Especially at first, people can remember and talk about events from earlier times in their lives. As the dementia progresses and more parts of the brain are affected, long-term memories may also start to fade.

Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Types of Dementia

One way to describe the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other types of dementia, is in “stages.” Stages are usually described as mild, moderate, and severe or early, middle, and late. Even though disease progression differs from person to person, we nevertheless associate certain symptoms and behaviors with these stages. The type of dementia, along with a person’s underlying medical condition, general health, family support, and co-morbid conditions can affect how fast and how far the dementia progresses from one stage to another.

Promoting Research

In this course, we will describe the stages of dementia as mild, moderate, or severe. For diagnostic and research purposes, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association have published guidelines aimed at improving current diagnosis, strengthening autopsy reporting of Alzheimer's brain changes, and promoting research into the earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Their guidelines describe the stages of Alzheimer’s disease as: (1) preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, (2) mild cognitive impairment, and (3) Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: the stage in which changes have begun to appear in the brain but no cognitive or emotional symptoms are present.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): characterized by a decline in cognitive function that falls between the changes associated with typical aging and changes associated with dementia.

- Dementia phase: a period in which symptoms become more obvious and independent living becomes more difficult.

Source: Alzheimer’s Association, 2021c.

Mild Dementia

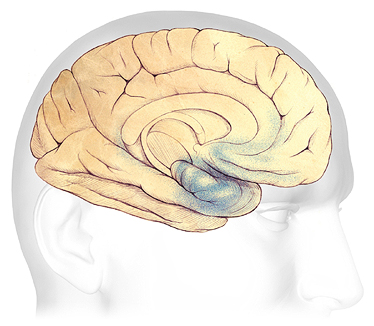

Brain Changes in Mild Dementia

In the early stages of AD, before symptoms can be detected, plaques and tangles form in and around the hippocampus (shaded in blue), an area of the brain responsible for the formation of new memories. Source: The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

In the early, mild stage of Alzheimer’s disease, plaques and tangles begin to damage the temporal lobes in and around the hippocampus. The hippocampus is part of the brain’s limbic system and is responsible for the formation of new memories, spatial memories, and navigation—and is also involved with emotions.

At this stage, changes that have been developing over many years begin to affect memory, decision-making, and complex planning. A person with mild dementia can still perform all or most activities of daily living such as shopping, cooking, yard work, dressing, bathing, and reading but will likely begin to need help with complex tasks such as balancing a checkbook and planning for the future.

Neuroimaging tests, which show changes in brain volume and amyloid levels indicate that the areas or the brain associated with events that occurred in the last few minutes are the first to show signs of deterioration. Brain regions associated with memories of the distant past decline at a later stage of the disease, but more rapidly.

Moderate Dementia

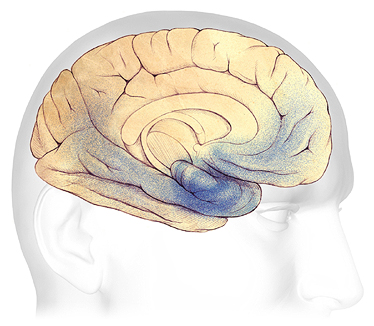

Brain Changes in Moderate Dementia

In mild to moderate stages, plaques and tangles spread from the hippocampus forward to the frontal lobes (shaded in blue). Source: The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses from the mild to moderate stage, plaques and tangles spread forward to areas of the brain involved with language, judgment, and learning. Speaking and understanding speech, spatial awareness, and executive functions such as planning, judgment, and ethical thinking are affected. Many people are first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in this stage.

In the moderate or middle stage, work and social life become more difficult and confusion increases. Damage spreads to the areas of the brain involved with:

- Speaking and understanding speech

- Logical thinking

- Safety awareness

Severe Dementia

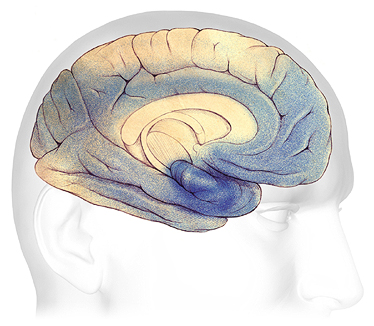

Brain Changes in Severe Dementia

In advanced Alzheimer’s, plaques and tangles have spread throughout the cerebral cortex (shaded in blue). Source: The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

In the advanced or severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease, damage is spread throughout the brain. At this stage, because so many areas of the brain are affected, people’s ability to communicate, to recognize family and loved ones, and to care for themselves is severely affected.

People with severe dementia lose memory of recent events although they may still remember events from long ago. They are easily confused, are unable to make decisions, cannot clearly communicate their needs, and can no longer think logically. Speech, communication, and judgment are severely affected. Sleep disturbances and emotional outbursts are very common.

Stages of Other Types of Dementia

Although generally dementia gets worse over time, other types of dementia can progress differently from Alzheimer’s disease. Because vascular dementia is caused by a stroke or series of small strokes, it may worsen suddenly and then stay steady for a long period of time. If the underlying cardiovascular causes are successfully addressed, dementia may stabilize.

In Lewy body dementia, which is often associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms—including cognitive abilities—can fluctuate drastically, even throughout the course of a day. Nevertheless, the dementia is progressive and worsens over time. In the later stages, progression is similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease.

In frontal-temporal dementia, which often starts at an earlier age than Alzheimer’s disease, symptoms nevertheless progress over time. In the early stages, people may have difficulty with just one type of symptom, such as planning, prioritizing, or multitasking. Other symptoms appear (inappropriate behaviors and comments, difficulty recognizing and responding to emotions) as more parts of the brain are affected.

Did You Know. . .

There are three subtypes of frontal-temporal dementia: (1) behavior and personality changes, (2) speech and language impairment, and (3) movement disorders.

Behavioral and personality changes can be mild at first, then become more extreme, leading to a progressive loss of judgement, loss of interest in normal activities, inappropriate social behaviors, and a decline in personal hygiene. Speech and language impairment can involve increasing difficulty understanding and using written and spoken language. Movement disorders, although rarer than the other subtypes, can include tremors, rigidity, muscle spasms, lack of coordination, and muscle weakness and wasting. These changes are progressive, becoming more pronounced as the dementia worsens.

In frontal-temporal dementia, the lobe of the brain affected impacts which symptoms first appear. If the disease starts in the part of the frontal lobe responsible for decision-making, then the first symptom might involve difficulty managing finances. If it begins in the part of the temporal lobe that connects emotions to objects, then the first symptom might be an inability to recognize potentially dangerous objects—for example, a person may not fear reaching for a rattlesnake or plunging a hand into boiling water (NIH, 2019).

Symptoms and Behavior Changes by Stages

A symptom is a change in the body or the mind. A behavior is how we act, move, and react to our environment. Symptoms change as dementia progresses, often affecting behavior. For some people symptoms can worsen quickly. For others, symptoms progress more gradually—over 10 to 20 years. A good way to understand this is to look at how symptoms and behaviors change in the early, middle, and late stages of dementia.

Symptoms and Behaviors in Mild Dementia

The early or mild stage of dementia begins with mild forgetfulness, especially memories of recent events. Forgetfulness might be the most obvious symptom at this stage, especially in Alzheimer’s disease. Logical thinking and judgment are mildly affected, especially in frontal-temporal dementia.

In the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as in other types of dementia, there might be a little confusion with complex, multi-step tasks. People naturally try to cover up mild confusion so friends, coworkers, and family might not notice that something is wrong. This behavior can be tiring, frustrating, and concerning for the person experiencing the first signs of cognitive change.

Even when symptoms are mild, behavior can begin to change, especially in Alzheimer’s disease. People with mild dementia often know something is wrong, which can cause depression, stress, and anxiety. Mood changes are common, particularly in someone with vascular dementia.

People struggling with the effects of mild dementia may become angry or aggressive. They might have difficulty making decisions. They will ask for help more often. They still might be able to work, drive, and live independently, but they will begin to need more help from family or coworkers.

Symptoms and Behaviors in Moderate Dementia

In the moderate stage of dementia, people become more forgetful and confusion worsens. Speech and communication are obviously affected. Judgment and logical thinking are much worse than in the early or mild stage.

Because of memory problems and confusion, caregivers must take over tasks that the person with dementia was able to do in the past. In this stage, travel, work, and keeping track of personal finances are much more difficult.

In the moderate stage, behavior changes are much more obvious. Inappropriate behaviors such as cursing, kicking, hitting, and biting are not uncommon. Some people may begin to repeat questions over and over, call out, or demand your attention. Sleep problems, anxiety, agitation, and suspicion can develop.

A person with moderate dementia is usually still able to walk. This is because the part of the brain that controls movement is not affected. If a person can still walk, or if they can get around easily in a wheelchair, they might begin to wander. More direct monitoring is needed than during the early stage of dementia. During this stage, people are no longer safe on their own. Caregiver responsibilities increase. This causes stress, anxiety, and worry among family members and caregivers.

Symptoms and Behavior in Severe Dementia

My mom is 96 years old and has pretty severe dementia. She lives at home with 24/7 care. If we put her in a nursing home, she would not survive. Loud noises, people that don’t know her needs and habits, boredom, loneliness—those things would drive her crazy. I’m sure she’d wander, yell, swear, shout, hit, and cry. At home she almost never does any of these things, but we work hard to keep things quiet, warm, and steady for her.

Family Caregiver, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida

People with severe dementia lose most or all memory of recent events although they may still remember events from long ago. They are easily confused, lose much of their ability to think logically and sequentially, and find decision-making difficult. Speech, communication, and judgment are severely affected. Sleep disturbances are common.

All sorts of challenging behaviors can occur in people with severe dementia—especially if caregivers are untrained, easily frustrated, or highly stressed. Wandering, rummaging, or hoarding can occur. A person may become paranoid or have delusions or hallucinations. Screaming, swearing, crying, shouting, loud demands for attention, negative remarks to others, and self-talk are common. These outbursts are often triggered by frustration, boredom, loneliness, depression, cold or heat, loud noises, and pain.

In the severe stage, a great deal of independence has been lost and around-the-clock care may be needed. Caregivers will likely need to oversee and directly assist with eating, bathing, walking, dressing, and other daily living activities.

Symptoms and Behavior at the End of Life

As people with dementia approach the end of life, they may lose all memory—not just memory of recent events. They are startled by loud noises and quick movements. They can no longer communicate their needs and desires using speech. At this stage, people may develop other illnesses and infections. They may experience agitation, psychosis,* delirium,** restlessness, and depression.

*Psychosis: loss of contact with reality.

**Delirium: a sudden, severe confusion that can be caused by infections, a reaction to medications, surgery, or illness.

At the end of life, people are completely dependent on caregivers. They may be unable to eat, swallow fluids, or move without help. Dementia becomes so severe that people may be bedridden. Severe dementia frequently causes complications such as immobility, swallowing disorders, and malnutrition that significantly increase the risk of acute conditions that can cause death. One such condition is pneumonia, which is the most common cause of death among older adults who have Alzheimer’s or other dementias.

Challenges for Caregivers at Each Stage

I’ve been hired to help care for a woman with mild dementia. She has five kids who come to their mother to discuss their personal problems. When they talk about their problems, I notice the mom always agrees with them, but when they leave she turns around and says, “I can’t stand to hear all their complaints.”

She gets really agitated after they visit. Sometimes she sits and cries for the rest of the day and I can’t snap her out of it. She didn’t used to be like this. I get so tired that it almost isn’t worth it—I never get any sleep when I’m there. I finally had to cut back from 7 to 4 days—it was really difficult caring for this woman.

Professional Caregiver, Miami, Florida

A caregiver is someone who provides assistance to a person in need. Care can be physical, financial, or emotional. Each year, more than 11 million family members and friends provide over 15 billion hours of unpaid care to those with Alzheimer’s and other dementias (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021b).

A daughter providing care for her aging mother. Source: NIA/NIH, public domain.

Caregivers help with basic activities such as bathing, dressing, walking, and cooking. They also help with more complex tasks such as managing medications and taking care of the home. Caregiver’s can provide direct care or manage care from a distance. Dementia caregiving is usually the responsibility of the spouse or an adult child.

Caregiving for individuals with dementia is more stressful than caregiving for individuals with many other diseases. Caring for aging adults with dementia is associated with increases in burden, distress, and declines in mental health and well-being. This is because dementia caregiving is characterized by specific problems such as the lack of free time, isolation from others, behavioral problems and personality changes, and fewer positive experiences resulting from the lack of expressed gratitude by the care recipient (Elnasseh et al., 2016).

The responsibilities of caregiving can be overwhelming. More than half of Alzheimer’s and dementia caregivers rate the emotional stress of caregiving as high or very high. About 40% of caregivers report symptoms of depression. One in five cut back on their own doctor visits because of their care responsibilities. And, among caregivers, 3 out of 4 report they are "somewhat" to “very” concerned about maintaining their own health since becoming a caregiver (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021).

Family dynamics are an important part of the caregiving experience. Family communication, adaptability/flexibility, and marital cohesion have all been connected to the emotional functioning of caregivers. Depression and anxiety are more likely to occur among caregivers in families with poor functioning, and conflicted family dynamics can intensify caregiver depression and caregiver strain. The poor functioning of families is likely to result in a decrease in the time spent on patient care, potentially impacting the quality of care the individual with dementia receives (Elnasseh et al., 2016).

Conversely, healthier family dynamics, such as family support, are associated with lower levels of caregiver strain. When families give more support to primary caregivers, they are often able to provide more help to the individual with dementia. Caregivers experience less burden and depression when family cohesion is high, and greater family communication also plays an important role in reducing caregiver burden (Elnasseh et al., 2016).

Even though the majority of research has focused on burden and other negative aspects of family caregiving, positive aspects have been presented, including a sense of meaning, a sense of self-efficacy, satisfaction, a feeling of accomplishment, and improved wellbeing and quality of relationships. These positive experiences can help sustain family members in their work as caregivers (Tretteteig et al., 2017).

Daughter assisting her mother with bills. Source: NIA/NIH.

In the early stage of dementia, family caregivers may not know much about dementia and may not seek help. They may be confused and frustrated when their family member “acts funny.” During this time, caregiving responsibilities and duties can usually be handled by family members. The person with dementia may only need help with complex activities such as banking, bill paying, medical appointments, and medications. People with mild dementia may still live alone, drive, and even have a job. They can usually handle activities of daily living such as bathing, eating, and cooking.

In the moderate stage, the time needed to care for a previously independent person increases. It can cause anxiety, stress, sleep disruption, anger, and depression. Loss of free time, work conflicts, and family issues may seem impossible to resolve. Often the responsibility of caregiving falls mostly on one person—generally a woman—leading to anger and frustration with other family members.

In the later stages of dementia, when fulltime care is needed, family members face difficult decisions and primary caregivers can become overburdened. Should the person with dementia move in with a family member? Should a full-time caregiver be hired? Should their loved one be admitted to a long-term care facility?

Behaviors such as agitation, irritability, obscene language, tantrums, and yelling are embarrassing, tiring, and frustrating for caregivers. Caregivers can be injured if a person throws things, strikes out, or bites. Caregivers may react out of fear and strike back or yell to stop these behaviors, creating guilt and more frustration.

I’m exhausted. I can’t sleep because I have to watch out for my wife. She wanders around the house, takes out all kinds of stuff from the kitchen. I never know what she’s going to do.

Family Caregiver, West Palm Beach, Florida, 2020

In this stage, safety is a challenge for caregivers. A one-on-one caregiver may be needed during the day. Spouses and family members become exhausted tending to a person who needs constant supervision. Jobs, hobbies, friendships, travel, and exercise fall to the side. Caregivers often neglect their own health, causing more stress.

If the person with dementia is still living at home, caregivers try to provide more support. Family members may find it impossible to continue to provide care and may decide to move their loved one to an assisted living or skilled nursing facility. Although this reduces caregiver burden, it does not relieve spouses and family members of the stress of continuing to worry about and manage care for their loved one.

Belonging to an ethnic minority group can lead to inequalities in diagnosis and care access in dementia. People from black and minority ethnic groups often experience delays in receiving a diagnosis, which leads to inequalities in accessing post diagnostic care, including anti-dementia medication (Giebel, 2020).