Normal aging carries with it a gradual decline of mental and physical functions. For most people, we can’t run as fast, jump as high, lift as much, or remember things as easily as when we were younger. Some of these changes are due to deconditioning, lack of exercise, and diet. But even healthy older adults in good physical condition experience a decline in physical performance, strength, reaction time, and balance. These age-related changes are a normal part of aging and usually do not interfere with the ability to live independently.

Normal Brain Changes with Age

An aging brain—one not affected by dementia—experiences changes. Certain parts of the brain shrink a little although there is not a significant loss of nerve calls, as occurs in Alzheimer’s disease. Shrinkage typically is found in the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, areas of the brain important to learning, memory, planning, and other complex mental activities. There are also normal changes in neurotransmitters, which affect communication between nerve cells.

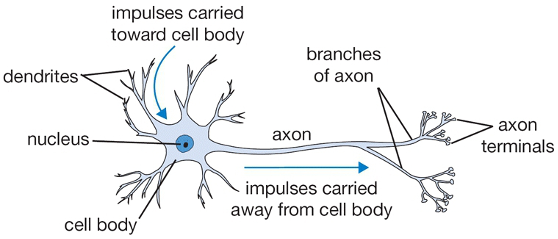

In certain brain regions, white matter (myelin-covered axons) is degraded or lost. This affects our brain’s ability to send and receive nerve impulses and to interact with neurons in other parts of the brain. When axons lose some of their ability to transmit a nerve signal efficiently, brain function is affected.

An illustration of a healthy neuron showing the nucleus, cell body, dendrites, and axons. Source: WPClipArt.com. Used with permission. From http://www.wpclipart.com/medical/anatomy/cells/neuron/neuron.png.html

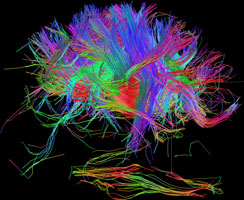

Because white matter connects the different regions of the brain, even a little loss or breakdown of myelin can affect cognition. You can see in the following images the massive amount of white matter within the human brain.

White matter fiber architecture of the brain. Measured from diffusion spectral imaging (DSI). The fibers are color-coded by direction: red = left-right, green = anterior-posterior, blue = through brain stem. Source: www.humanconnectomeproject.org. From http://www.humanconnectomeproject.org/gallery/ L = row 12, #2 R=row 9, #3

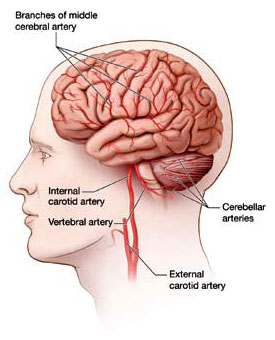

As we age, changes in the brain’s blood vessels can also occur. Blood flow can be reduced because arteries narrow and there is less growth of new capillaries.

The main arteries supplying blood to the brain. The brain receives blood through a vast network of arteries, arterioles, and capillaries. As we age, this network is less efficient than when we were young.

Due to these normal, age-related changes, some healthy older adults may notice a modest decline in their ability to learn new things and retrieve information. Older adults may not perform as well on complex tasks of attention, learning, and memory compared to younger people. However, if given enough time to perform the task, the scores of healthy people in their 70s and 80s are often similar to those of young adults. In fact, as we age, adults often improve in other cognitive areas, such as vocabulary and other forms of verbal knowledge (NIA, 2019).

Cognitive training can counteract age-related structural and functional losses; memory training can increase the thickness of the cerebral cortex. Memory training has been shown to enhance activity in the hippocampus during memory retrieval in clients with mild cognitive impairment. Physical exercise has also been found to affect brain function positively (Zheng et al., 2015).

As we age, walking speed and stride length decrease, while lateral sway increases. But because of the flexibility of our brain—called neural plasticity—these age-related changes can be partly compensated for through conscious effort. In this way, deficits in one part of the nervous system can be overcome by engaging another part of that system (Beurskens & Bock, 2012).

Differentiating Normal Aging and Dementia

Someone with age-related changes can easily do activities of daily living—they can prepare their own meals, drive safely, go shopping, and use a computer. They understand when they are in danger and have good judgment. They know how to take care of themselves. Even though they might not think or move as fast as when they were young, their thinking is normal—they do not have dementia.

Dementia, by contrast involves the impairment of memory and other cognitive functions (language, learned motor skills, visuospatial/sensory skills, executive functions). The impairments need to be sufficiently severe to affect social or professional life, and must not occur as a consequence of delirium, or be caused by another medical, neurologic, or psychiatric condition (Chertkow et al., 2013).

Mild Cognitive Impairment

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) represents a stage of cognitive function between the expected decline seen in healthy aging and that seen in dementia. Individuals with MCI have a more pronounced cognitive impairment than what would be expected for their age and education, but do not meet functional criteria for dementia (Moreira et al., 2019).

Although mild cognitive impairment has been described as a transitional stage between normal cognitive aging and dementia, particularly Alzheimer's disease, studies suggest that individuals diagnosed with this disorder do not always progress to Alzheimer's disease and may even revert to normal (Lee et al., 2014).

The onset of mild cognitive impairment has traditionally been associated with cognitive decline that affects social and occupational functioning and is accompanied by changes in behavior and personality (Chertkow et al., 2013). There are no tests that reliably indicate the presence of mild cognitive impairment; differentiating normal aging and mild cognitive impairment relies on screening, assessment, and client history (DeFina et al., 2013).

Cognitive Reserve and Cognitive Health

Cognitive reserve is a theoretical concept that suggests that individuals differ in their degree of resilience against age-related brain pathology. These differences are linked to the ability of an individual to recruit protective mechanisms associated with cognitive abilities built up over the lifespan, and actively compensate for damage caused by pathology (Evans et al., 2018).

Cognitive reserve highlights the brain’s ability to operate effectively even when some of its function is disrupted. It also refers to the amount of damage that the brain can sustain before changes in cognition are evident. People vary in cognitive reserve because of differences in genetics, education, occupation, lifestyle, leisure activities, or other life experiences. These factors may provide the ability to adapt to change and damage that occurs during aging.

For one individual, depending on a person’s cognitive reserve and unique mix of genetics, environment, and life experiences, the balance may tip in favor of a disease process that will ultimately lead to dementia. For another person, with a different reserve and a different mix of genetics, environment, and life experiences, the balance may result in no apparent decline in cognitive function with age (NIH, 2016).

Observational and some experimental evidence suggests that reserve can be built up through a combination of experiences throughout life, such as physical exercise, education, occupation, and participation in social and cognitively stimulating activities. These experiences may create a buffer against cognitive decline by enhancing brain processes such as neural connectivity and hence cognitive ability. This might protect an individual against the effects of disease pathology, compensate for damage, and recruit alternative neural pathways when required. This may reduce or delay the extent of impairment experienced and protect against the expression of pathological processes (Evans et al., 2018).

Cognitive health is a major factor in ensuring the quality of life of older people and preserving independence. Cognitive health is the development and preservation of a cognitive structure that allows older people to maintain social connectedness, an ongoing sense of purpose, and the ability to function independently, to successfully recovery from illness or injury, and to cope with any functional deficits. The key components of cognitive health are mental abilities and acquired skills, as well as the ability to apply these skills in purposeful activity (Clare et al., 2017).