Although dementia has probably been around since the first humans appeared on the earth, it is only as we live longer that we have begun to see its widespread occurrence in older adults. The most common—and perhaps most familiar—type of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, but there are other types and causes of dementia. In fact, new research is suggesting that “pure” pathologies may be rare and most people likely have a mix of more than one type of dementia. Worldwide more than 35 million people live with dementia and this number is expected to double by 2030 and triple by 2050 (ADI, 2013).

Defining Dementia

The ugly reality is that dementia often manifests as a relentless and cruel assault on personhood, comfort, and dignity. It siphons away control over thoughts and actions, control that we take for granted every waking second of every day.

Michael J. Passmore

Geriatric Psychiatrist, University of British Columbia

Dementia is a collective name for progressive, global deterioration of the brain’s executive functions. Although there are notable exceptions, dementia occurs primarily in later adulthood and represents a major cause of disability in older adults. Almost everyone with dementia is elderly but nevertheless dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

Although the exact cause of dementia is still unknown, in Alzheimer’s disease, and likely in other forms of dementia, damage within the brain is related to a so-called pathological triad: (1) formation of extracellular beta-amyloid plaques; (2) disruption of the normal function of a protein called tau, which leads to the development of neurofibrillary tangles; and (3) degeneration of cerebral neurons (Lobello et al., 2012).

Inside the Brain: Unraveling the Mystery of Alzheimer’s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NjgBnx1jVIU (video 4:21)

In Alzheimer’s disease, damage begins in the temporal lobe, in and around the hippocampus. The hippocampus is part of the brain’s limbic system and is responsible for the formation of new memories, spatial memories and navigation, and is also involved with emotions.

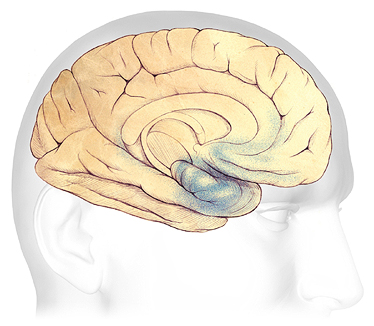

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease

In the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, before symptoms can be detected, plaques and tangles form in and around the hippocampus (shaded in blue).

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

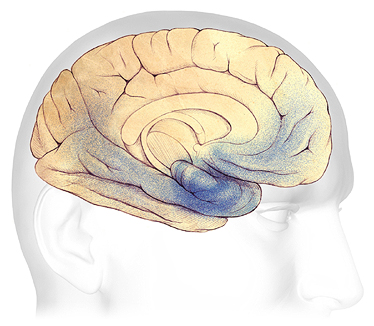

As the disease progresses, plaques and tangles spread to the front part of the brain (the temporal and frontal lobes). These areas of the brain are involved with language, judgment, and learning. Speaking and understanding speech, the sense of where your body is in space, and executive functions such as planning and ethical thinking are affected.

Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease

In mild to moderate stages, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) spread from the hippocampus forward to the frontal lobes.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

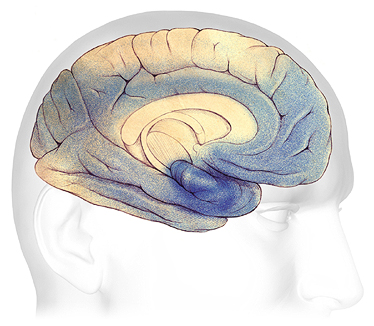

In severe Alzheimer’s disease, damage is spread throughout the brain. Notice in the illustration below the damage (dark blue) in the area of the hippocampus, where new, short-term memories are formed. At this stage, because so many areas of the brain are affected, individuals lose their ability to communicate, to recognize family and loved ones, and to care for themselves.

Severe Alzheimer’s Disease

In advanced Alzheimer’s, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) have spread throughout the cerebral cortex.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

It is now thought that the brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease begin years, or even decades, before symptoms emerge. The changes eventually reach a threshold at which the onset of a gradual and progressive decline in cognition becomes obvious (DeFina et al., 2013).

Types of Dementia

Although Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, it isn’t the only cause. Frontal-temporal dementia—which begins in the frontal lobes—is a relatively common type of dementia in those under the age of 60. Vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia are other common types of dementia (see table). In all, nearly twenty different types of dementia have been identified.

|

Some Common Types of Dementia |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dementia subtype |

Early, characteristic symptoms |

Neuropathology |

% of dementia cases |

|

*Alzheimer’s disease (AD) |

|

|

50–75% |

|

Frontal-temporal dementia |

|

|

5–10% |

|

*Vascular dementia |

|

|

20–30% |

|

Dementia with Lewy-bodies |

|

Cortical Lewy bodies (alpha-synuclein) |

<5% |

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is based on symptoms. This generally includes a gradual decline in mental capacity, changes in behavior, and the eventual loss of the ability to live independently. As yet, there is no blood test or imaging technique that can definitively diagnose dementia.

In 2009 the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) developed updated guidelines for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. The diagnostic criteria for AD, published in 2011, are as follows:

- A gradual, progressive decline in cognition that represents a deterioration from a previous higher level;

- Cognitive or behavioral impairment evident in at least two of the following domains:

- episodic memory,

- executive functioning,

- visuospatial abilities,

- language functions,

- personality and/or behavior;

- Significant functional impairment that affects the individual’s ability to carry out daily living activities;

- A situation in which symptoms are not better accounted for by delirium or another mental disorder, stroke, another dementing condition (i.e., vascular dementia, frontal-temporal dementia) or other neurological condition, or the effects of a medication. (DeFina et al., 2013)

The recently released Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5) contains updated criteria for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease which parallel the NIA-AA diagnostic guidelines. Clinicians should familiarize themselves with these revised criteria, listed within the Neurocognitive Disorders section of the DSM-V because the criteria contained in the prior DSM-IV-TR are not reflective of the current state of the AD literature (DeFina et al., 2013).

Primary Care Barriers to Diagnosis

Primary care offices are usually responsible for medical management of most cases of dementia. However, the average primary care clinician may have difficulty providing optimal care. Clinicians face a number of barriers (Lathern et al., 2013):

- Insufficient time

- Insufficient support staff

- Difficulty accessing specialists

- Low reimbursement

- Poor connections with community social service agencies

In addition, numerous studies have found that primary care physicians may lack knowledge or skill for appropriate screening, diagnosis, and treatment of dementia. These barriers often result in delayed or overlooked dementia diagnoses and missed opportunities for treatment, care planning, and support for family members (Lathern et al., 2013).

In a retrospective study of veterans diagnosed with dementia in the Veteran’s Administration (VA) New England Healthcare System, researchers found that few patients had a diagnosis of cognitive impairment prior to their first dementia diagnosis. This is despite the fact that many of them have been followed in the VA system for years. Compared to patients who see a geriatrician or neurologist, dementia patients followed up exclusively by primary care physicians are less likely to receive a specific dementia diagnosis and less likely to have their initial diagnosis change over time. They are also less likely to have neuroimaging or receive dementia medication (Cho et al., 2014).

There is a growing appreciation of the importance of early recognition of dementia. Patients with unrecognized impairment do not get tested for reversible causes of dementia, do not get counseling regarding the disease process or advanced care planning, and are not offered treatment (Cho et al., 2014).

Agreement Between Diagnosis and Pathology

A number of studies have examined the agreement between the diagnosis made while the person is alive and the pathology found in the postmortem brain. These studies have suggested that mixed pathologies are more common than “pure” pathologies—meaning most people have a mixture of two or more types of dementia. This is particularly true for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, and for Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies (ADI, 2009).

In findings from the BrainNet Europe Consortium, a consortium of brain banks in Europe and the United Kingdom, upon autopsy, a little more than half of patients had mixed diagnoses among all cases of dementia. The presence of multiple brain pathologies markedly increases the odds of cognitive impairment (Herrmann et al., 2013).

In their clinical practice guideline for dementia, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence noted the high prevalence of mixed pathology and suggested management according to the predominant cause. This recommendation recognizes how commonly mixed pathologies underlie dementia and gives management advice to practicing physicians (Herrmann et al., 2013).

Neuroimaging and Biomarkers

Neuroimaging—particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET)—is emerging as a potential diagnostic tool for dementia. These techniques may assist with early diagnosis of AD by detecting visible, abnormal structural and functional changes in the brain (Fraga et al., 2013).

Positron Emission Tomography

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is a functional imaging technique that shows how well cells in various brain regions are working by looking at how actively the cells use sugar or oxygen. PET can also detect changes at a molecular level and may be a promising tool to detect very early changes in the brain.

Advances in PET imaging make it possible to detect beta amyloid plaques using a radiolabeled compound called Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB). This substance binds to beta amyloid plaques in the brain and can be imaged using PET scans. Initial studies have shown that people with AD take up more PiB in their brains than do cognitively healthy older people. Researchers have also found high levels of PiB in some cognitively healthy people, suggesting that the damage from beta amyloid may already be underway (NIA, 2014).

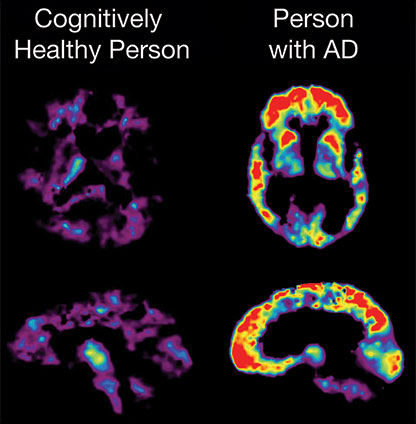

PET Scans Showing PiB Uptake

In this PET scan, the red and yellow colors indicate that PiB uptake is higher in the brain of the person with AD than in the cognitively healthy person. Source: NIA, public domain.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Structural imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide information about the shape, position, and volume of the brain tissue. Magnetic resonance imaging is being used to detect cerebral atrophy, which is likely the result of excessive neuronal death. Atrophy correlates closely with the rate of neuropsychological decline in patients with AD.

Functional MRI, currently in the testing phase, is a technique that picks up small, MRI-measurable signals in response to increases in brain activity. It can be used to examine brain regions where activity changes when people are asked to process different kinds of information, use different types of thinking skills, or respond in different ways (Human Connectome Project, 2014).

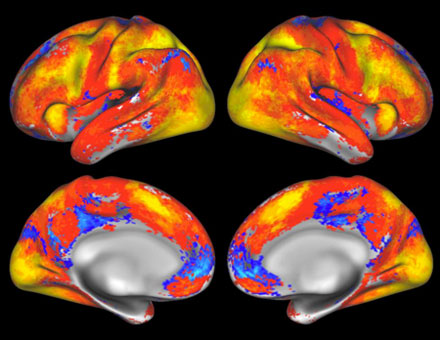

Task Functional MRI (fMRI)

A map of overall task-fMRI brain coverage from the seven tasks used in the Human Connectome Project. Yellow and red represent regions that become more active in most participants during one or more tasks in the MR scanner; blue represents regions that become less active. Source: D.M. Barch for the WU-Minn HCP Consortium.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers are changes in sensory and cognitive abilities or substances in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or urine. Biomarkers can indicate exposure to a substance, the presence of a disease, or disease progression over time. Elevated levels of tau protein in the cerebrospinal fluid is a mark of active neuronal degeneration, while levels of abnormally phosphorylated* tau appear to correlate with the quantity of neurofibrillary tangles in the brain (Lobello et al., 2012).

*Phosphorylation: a process that turns many protein enzymes on and off, thereby altering their function and activity. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau proteins are abnormally altered by phosphorylation, which allows them to aggregate and form neurofibrillary tangles.

Conditions That Can Mimic Dementia

A number of medical conditions have symptoms that mimic those of dementia. These conditions must be considered when evaluating someone with cognitive changes. Gerontology specialists speak of the “3Ds”—dementia, delirium, and depression—because these three conditions are the most prevalent reasons for cognitive impairment in older adults. Delirium and depression can cause cognitive changes that may be mistaken for dementia. Clinicians and caregivers should learn to distinguish the differences.

Delirium

Delirium (also called acute confusion) is a sudden, severe confusion with rapid changes in brain function and a fluctuating course. Delirium develops over hours or days and is temporary and reversible.

Delirium can cause changes in perception, mood, cognition, and attention. The most common causes of delirium, which are usually identifiable, are related to medication side effects, hypo or hyperglycemia, fecal impactions, urinary retention, electrolyte disorders and dehydration, infection, stress, metabolic changes, an unfamiliar environment, injury, or severe pain.

Delirium: A Patient Story at Leicester’s Hospital (6:49)

NHS Leicester’s Hospital, England, U.K.

The prevalence of delirium is known to increase with age, and nearly 50% of patients over the age of 70 experience episodes of delirium during hospitalization. Delirium is under-diagnosed in almost two-thirds of cases or is misdiagnosed as depression or dementia. Since the most common causes of delirium are reversible, recognition enhances early intervention (Hope et al., 2014).

Early diagnosis of delirium can lead to rapid improvement. Nevertheless, diagnosis is often delayed, and problems remain with recognition and documentation of delirium by nurses and physicians. Although there are no definitive quantitative markers available to diagnose delirium, qualitative tools such as the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and modified Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale have been validated. Unfortunately, the use of these tools has not generalized and nurses often simply record the patient’s mental status in narrative (Hope et al., 2014).

Depression

Major depressive disorder is characterized by a combination of symptoms that interfere with a person’s ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy once-pleasurable activities. Some people may experience only a single episode within their lifetime, but more often a person may have multiple episodes (NIMH, n.d.).

Dysthymic disorder, or dysthymia, is characterized by long-term (2 years or longer) symptoms that may not be severe enough to disable a person but can prevent normal functioning or feeling well. People with dysthymia may also experience one or more episodes of major depression during their lifetimes.

Minor depression is characterized by symptoms lasting 2 weeks or longer that do not meet full criteria for major depression. Without treatment, people with minor depression are at high risk for developing major depressive disorder (NIMH, n.d.).

Signs and symptoms of depression include:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” feelings

- Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Irritability, restlessness

- Loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex

- Fatigue and decreased energy

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering details, and making decisions

- Insomnia, early-morning wakefulness, or excessive sleeping

- Overeating or appetite loss

- Thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts

- Aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems that do not ease even with treatment (NIMH, n.d.)

Comorbid depression is very common among those with dementia. A review of the literature reported that almost one-third of long-term care residents have depressive symptoms, while an estimated 10% meet criteria for a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder (Jordan et al., 2014).

Despite the awareness of the high prevalence of depression in the long-term care population, there is both a high occurrence and under-treatment of depression within these settings. Depressive illness is associated with increased mortality, risk of chronic disease, and the requirement for higher levels of supported care (Jordan et al., 2014).

Long-term care staff can play a key role in the detection, assessment, management, and ongoing monitoring of mental health disorders among their care recipients; however, research suggests that these staff receive little training in mental health and commonly hold misconceptions about disorders such as depression and the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. As a result, they have demonstrated poor skills in managing residents with these disorders (Jordan et al., 2014).

|

Comparing Dementia, Delirium, and Depression |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Delirium |

Depression |

Dementia |

|

Onset |

Rapid, hours to days |

Rapid or slow |

Progressive, develops over several years |

|

Cause |

Medications, infection, dehydration, metabolic changes, fecal impaction, urinary retention, hypo and hyperglycemia |

Alteration in neurotransmitter function |

Progressive brain damage |

|

Duration |

Usually less than one month but can last up to a year |

Months, can be chronic |

Years to decades |

|

Course |

Reversible, cause can usually be identified |

Usually recover within months; can be relapsing |

Not reversible, ultimately fatal |

|

Level of consciousness |

Usually changed, can be agitated, normal, or dull, hypo or hyperactive |

Normal or slowed |

Normal |

|

Orientation |

Impaired short-term memory, acutely confused |

Usually intact |

Correct in mild cases; first loses orientation to time, then place and person |

|

Thinking |

Disorganized, incoherent, rambling |

Distorted, pessimistic |

Impaired, impoverished |

|

Attention |

Usually disturbed, hard to direct or sustain |

Difficulty concentrating |

Usually intact |

|

Awareness |

Can be reduced, tends to fluctuate |

Diminished |

Alert during the day; may be hyperalert |

|

Sleep/waking |

Usually disrupted |

Hyper or hypo somnolence |

Normal for age; cycle disrupted as the disease progresses |