Although dementia has probably been around since humans first appeared on earth, it is only as we live longer that we have begun to see its widespread occurrence in older adults. The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, but there are other types and causes of dementia. In fact, new research is suggesting that “pure” pathologies may be rare and most people likely have a mix of more than one type of dementia.

Worldwide more than 47 million people live with dementia and because people are living longer this number is expected to triple by 2050 (ADI, 2016). In Florida, there are 510,000 residents currently living with Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016) and by 2025, this number is expected to increase by more than 200,000.

Defining Dementia

The ugly reality is that dementia often manifests as a relentless and cruel assault on personhood, comfort, and dignity. It siphons away control over thoughts and actions, control that we take for granted every waking second of every day.

Michael J. Passmore, Geriatric Psychiatrist

University of British Columbia

Dementia is a collective name for the progressive, global deterioration of the brain’s executive functions. Dementia occurs primarily in later adulthood and is a major cause of disability in older adults. Although almost everyone with dementia is elderly dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

The exact cause of dementia is still unknown. In Alzheimer’s disease, and likely in other forms of dementia, damage within the brain is related to a so-called pathological triad: (1) formation of beta-amyloid plaques; (2) disruption of a protein called tau leading to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles; and (3) degeneration of cerebral neurons (Lobello et al., 2012). These processes are clearly explained in the following video.

Inside the Brain: Unraveling the Mystery of Alzheimer’s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NjgBnx1jVIU (video 4:21)

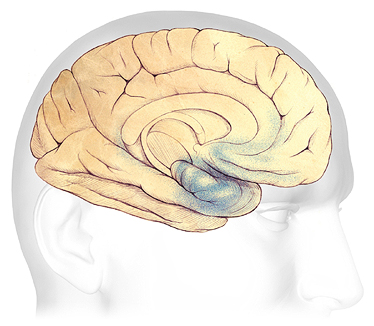

In Alzheimer’s disease, damage begins in the temporal lobe, in and around the hippocampus. The hippocampus is part of the brain’s limbic system and is responsible for the formation of new memories, spatial memories and navigation, and is also involved with emotions.

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease

In the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, before symptoms can be detected, plaques and tangles form in and around the hippocampus (shaded in blue).

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

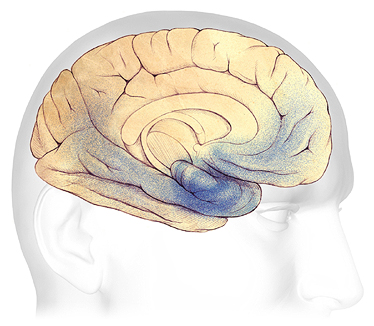

As the disease progresses, plaques and tangles spread to the front part of the brain (the temporal and frontal lobes). These areas of the brain are involved with language, judgment, and learning. Speaking and understanding speech, the sense of where your body is in space, and executive functions such as planning and ethical thinking are affected.

Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease

In mild to moderate stages, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) spread from the hippocampus forward to the frontal lobes.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

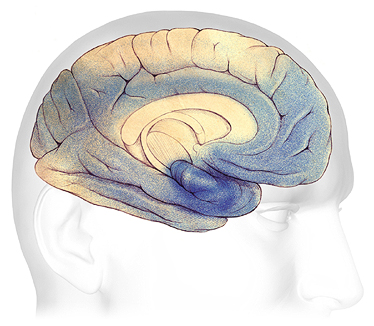

In severe Alzheimer’s disease, damage is spread throughout the brain. Notice in the illustration below the damage (dark blue) in the area of the hippocampus, where new, short-term memories are formed. At this stage, because so many areas of the brain are affected, individuals lose their ability to communicate, to recognize family and loved ones, and to care for themselves.

Severe Alzheimer’s Disease

In advanced Alzheimer’s, plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) have spread throughout the cerebral cortex.

Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

It is now thought that the brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease begin years, or even decades, before symptoms emerge. The changes eventually reach a threshold at which the onset of a gradual and progressive decline in cognition becomes obvious (DeFina et al., 2013).

Types of Dementia

Although Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, it isn’t the only cause. Frontal-temporal dementia—which begins in the frontal lobes—is a relatively common type of dementia in those under the age of 60. Vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia are other common types of dementia (see table). In all, nearly twenty different types of dementia have been identified.

Some Common Types of Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Dementia subtype | Early, characteristic symptoms | Neuropathology | % of cases |

*Alzheimer’s disease (AD) |

|

| 50–75% |

Frontal-temporal dementia |

|

| 5–10% |

*Vascular dementia |

|

| 20–30% |

Dementia with Lewy-bodies |

| Cortical Lewy bodies (alpha-synuclein) | <5% |

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is based on symptoms; no test or technique that can diagnose dementia. To guide clinicians, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) has developed the following diagnostic guidelines indicating the presence Alzheimer’s disease:

- Gradual, progressive decline in cognition that represents a deterioration from a previous higher level;

- Cognitive or behavioral impairment in at least two of the following domains:

- episodic memory,

- executive functioning,

- visuospatial abilities,

- language functions,

- personality and/or behavior;

- Functional impairment that affects the individual’s ability to carry out daily living activities;

- Symptoms that are not accounted for by delirium or another mental disorder, stroke, another type of dementia or other neurological condition, or the effects of a medication. (DeFina et al., 2013)

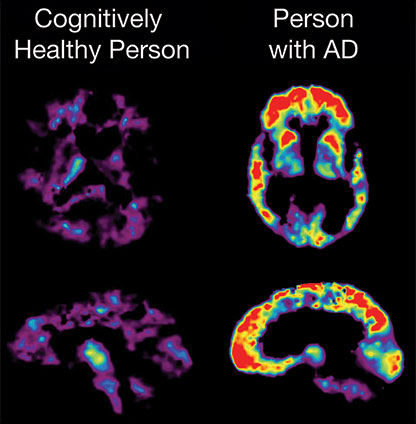

Neuroimaging shows promise is assisting with early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease by detecting visible, abnormal structural and functional changes in the brain (Fraga et al., 2013). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide information about the shape, position, and volume of the brain tissue. It is being used to detect brain shrinkage, which is likely the result of excessive nerve death. Positron emission tomography (PET) is being used to detect the presence of beta amyloid plaques in the brain.

PET Scans Showing PIB Uptake

PET imaging makes it possible to detect beta amyloid plaques using a radiolabeled compound called Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB). In this PET scan, the red and yellow colors indicate that PiB uptake is higher in the brain of the person with AD than in the cognitively healthy person. Source: NIA, public domain.

Conditions That Can Mimic Dementia

A number of medical conditions other than dementia can cause cognitive changes. Gerontology specialists speak of the “3Ds”—dementia, delirium, and depression—because these three conditions are the most common reasons for cognitive changes in older adults. Delirium and depression may be mistaken for dementia.

Delirium

Delirium is a sudden, severe confusion with rapid changes in brain function. Delirium develops over hours or days and is temporary and reversible. Delirium can affect perception, mood, cognition, and attention. The most common causes of delirium in people with dementia are medication side effects, hypo or hyperglycemia, fecal impactions, urinary retention, electrolyte disorders and dehydration, infection, stress, and metabolic changes. An unfamiliar environment, injury, or severe pain can also cause delirium.

Delirium is under-diagnosed in almost two-thirds of cases and can be misdiagnosed as depression or dementia. Since the most common causes of delirium are reversible, recognition enhances early intervention. Early diagnosis can lead to rapid improvement (Hope et al., 2014).

Delirium: A Patient Story at Leicester’s Hospital (6:49)

NHS Leicester’s Hospital, England, U.K.

Depression

Depression is a common but serious mood disorder. Major depressive disorder is characterized by a combination of symptoms that interfere with a person’s ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy activities. Some people may experience only a single episode within their lifetime, but more often a person may have multiple episodes (NIMH, 2016).

Persistent depressive disorder, or dysthymia, is characterized by longterm (2 years or longer) symptoms that may not be severe enough to disable a person but can prevent normal functioning or feeling well. Psychotic depression occurs when a person has severe depression plus some form of psychosis, such as delusions or hallucinations. Psychotic symptoms typically have a depressive “theme,” such as delusions of guilt, poverty, or illness (NIMH, 2016).

Depression is very common in people with dementia. Almost one-third of longterm care residents have depressive symptoms and about 10% meet criteria for a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Despite this awareness, depression is undertreated in people with dementia. Depressive illness is associated with increased mortality, risk of chronic disease, and higher levels of supported care (Jordan et al., 2014).