If leaders take the bold actions needed now to ensure sufficient and sustainable resourcing and protect everyone’s human rights, the number of people living with HIV, requiring life-long treatment, will settle at around 29 million by 2050 but if they take the wrong path, the number of people who will need life-long support will rise to 46 million (compared to 39.9 million in 2023).

UNAIDS, 2024b

1.1 Definitions of HIV and AIDS

[Note: If not otherwise identified, material in this course is taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.]

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has infected tens of millions of people around the globe in the past four decades, with devastating results. According to the CDC, as of 2021, 1.2 million people in the United States have HIV, and 13% of them have not received a diagnosis. In its advanced stage—acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)—the infected individual has no protection from diseases that may not even threaten people who have healthy immune systems. While there is not yet an effective cure—HIV is something one has for life once infected—proper medical care can control the virus, and long, quality lives are possible with effective, sustained HIV treatment. This treatment can also help provide protection for the partners of infected people.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) kills or impairs the cells of the immune system and progressively destroys the body’s ability to protect itself. Over time, a person with a deficient immune system (immunodeficiency) may become vulnerable to common and even simple infections by disease-causing organisms such as bacteria or viruses. These infections can become life-threatening.

The term AIDS comes from “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.” AIDS refers to the most advanced stage of HIV infection. Medical treatment can delay the onset of AIDS, but HIV infection eventually results in a syndrome of symptoms, diseases, and infections. People receive an AIDS diagnosis when their CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells per milliliter of blood, or they develop certain illnesses (sometimes called opportunistic infections). Only a licensed medical provider can make an AIDS diagnosis. A key concept is that all people diagnosed with AIDS have HIV, but an individual may be infected with HIV and not yet have AIDS.

1.2 HIV Infection in the Body

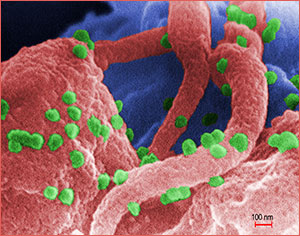

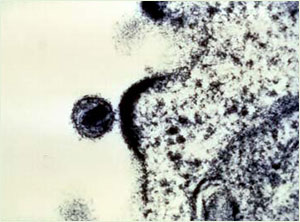

Human Lymphocyte Showing HIV Infection

Source: Public Health Image Library, image #11279, CDC, 1989.

HIV “Budding” Out of a T-cell

Source: NIAID, courtesy of Dr. Tom Folks.

A scanning electron micrograph showing HIV-1 virions (in green) on the surface of a human lymphocyte. HIV was identified in 1983 as the pathogen responsible for AIDS. In the infected individual, the virus causes a depletion of T-cells, which leaves these patients susceptible to opportunistic infections and to certain malignancies.

HIV enters the bloodstream and attacks T-helper lymphocytes, which are white blood cells essential to the functioning of the immune system. One of the functions of T-helper cells is to regulate the immune response in the event of attack from disease-causing organisms such as bacteria or viruses. The T-helper lymphocyte cell is also called the T4 or the CD4 cell. When any pathogen infects the T-helper lymphocyte, the T cell sends signals to other cells, which produce helpful antibodies.

Antibodies (proteins made by the immune system in response to infection) are produced by the immune system to help get rid of specific foreign invaders that can cause disease. Producing antibodies is an essential function of our immune system. The body makes a specific antibody for each pathogen. For example, if we are exposed to the measles virus, the immune system will develop antibodies specifically designed to attack that virus. Polio antibodies fight the polio virus. A healthy immune system creates customized identification of pathogens, which results in the body’s ability to target and kill invading microorganisms. When our immune system is working correctly, it protects against these foreign invaders.

HIV infects and destroys the T-helper lymphocytes and damages their ability to signal for antibody production. This results in the eventual decline of the immune system. The HIV is then able to reproduce without being killed from the body. CD4 counts therefore are of great importance to people with HIV to confirm their ability to fight infection. The normal range for CD4 is between 500 and 1,500. A CD4 count below 200 reveals the body’s inability to create antibodies and fight infection, putting the client at greater risk for AIDS and other potentially fatal opportunistic infections. Serum lab results may also express CD4 percentage, and a normal result in an HIV negative person is between 25% and 65%, identifying that percentage of lymphocytes are CD4 cells. The remaining cells are other types of lymphocytes also involved in the immune attack against pathogens.

When HIV is not treated, an infected person typically moves through three stages.

Stage 1: Acute HIV Infection

Acute HIV infection (sometimes called primary HIV infection or acute retroviral syndrome) is the first stage of HIV disease. It begins within 2 to 4 weeks of contracting HIV and lasts until the body has created antibodies to the virus, all while the virus is establishing itself in the body.

This period of acute infection is characterized by a high viral load (large numbers of the virus) and a decline in CD4 cells and during this time infected persons are very contagious. Within two to four weeks after infection most patients experience flu-like symptoms that can include fever, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, rash, muscle aches, night sweats, mouth ulcers, chills, and fatigue. These may last for only a few days or as long as several weeks, or there may be no symptoms at all. Because symptoms are not life-threatening and also occur with other illnesses, they may be misinterpreted. During this period, since newly infected people are very contagious and they do not yet know they have HIV, they can infect their partners.

The primary infection period ends when the body begins to produce HIV-specific antibodies as the CD4 cells are still able to respond. There are several types of HIV tests available, which are testing for different markers—antibodies, p24 antigen, or the actual virus. No test is effective sooner than 10 days after infection, however, each test has a different window period—the time between infection with HIV and the body’s production of detectable markers—and the first choice of test may depend on individual circumstances.

If a person has flu-like symptoms and suspects they have been exposed to HIV they should pursue appropriate testing as soon as possible. Important treatments can begin right away and help improve outcomes. Testing is reviewed in detail in part 3.

Stage 2: Chronic HIV Infection

In this stage, the virus is replicating and slowly destroying the immune system. Also called asymptomatic HIV infection or clinical latency, in this stage people infected with HIV continue to look and feel completely well for long periods, sometimes for many years. Although a person looks and feels healthy, they can still infect other people through any body-fluid contact such as unprotected anal, vaginal, or oral sex or through needle sharing. The virus can also be passed from an infected woman to her baby during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding when she is unaware of being HIV positive.

People with chronic HIV infection may not have any HIV-related symptoms. Without ART, chronic HIV infection usually advances to AIDS in 10 years or longer, though in some people it may advance faster. People who are taking ART may be in this stage for several decades. While it is still possible to transmit HIV to others during this stage, people who take ART exactly as prescribed and maintain an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to an HIV-negative partner through sex (HIVinfo.hih.gov, 2024).

At the end of this stage, the person’s viral load—the amount of HIV in the blood—goes up and the person may move to stage 3 or AIDS.

Apply Your Learning

Q: If a person has been infected with HIV but is not symptomatic, how would you explain this to a patient with HIV?

A: Although there may be no clinical symptoms, the HIV is replicating and slowly attacking the immune system’s CD4 cells. An untreated person can look and feel healthy, sometimes for many years, however the virus is still present in the blood and can cause infection in others. Also, the virus can be passed through unprotected sex and from pregnant or lactating mother to child.

Stage 3: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

This is the final, most severe HIV infection stage and people receive the diagnosis of AIDS when their CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells per milliliter of blood, or they develop certain illnesses known as opportunistic infections. At this point, a person’s immune system has been severely damaged, and opportunistic infections are infections and infection-related cancers that occur more frequently or are more severe in people with weakened immune systems than in people with healthy immune systems. Also, in this stage people can have a high viral load and easily transmit the virus to others. With no treatment, people at this stage usually survive about three years.

1.3 The Origin of HIV

Since the human immunodeficiency virus was identified in 1983, researchers have worked to pinpoint the origin of the virus. In 1999 an international team of researchers reported that they discovered the origins of HIV-1, the predominant strain of HIV in the developed world. A subspecies of chimpanzees native to West Equatorial Africa was identified as the original source of the virus. Researchers believe that HIV-1 was introduced into the human population when hunters became exposed to infected blood. The transmission of HIV was driven through Africa by migration, housing, travel, sexual practices, drug use, war, and economics that affect both Africa and the entire world.

1.4 HIV Types, Groups and Subtypes

HIV is divided into two primary types: HIV-1 and HIV-2. Worldwide, the predominant type is HIV-1, and generally when people refer to HIV without specifying the type of virus they are referring to HIV-1. The relatively uncommon HIV-2 type is concentrated in West Africa and rarely found elsewhere.

HIV-1 viruses are further classified into four groups: Group M, Group N, Group O, Group P. Viruses in Group M account for majority of HIV cases around the world (“M” actually stands for “major”). The other three groups are not as common and generally found only in certain areas in Africa. HIV-2 viruses are also divided into groups of which there are nine: A through I, with only A and D currently circulating in humans.

HIV-1 groups are also divided into subtypes. HIV-1 Group M has nine subtypes, and their prevalence varies in different areas of the world with Subtype B the main one in the United States. HIV-2 groups do not have subtypes.

HIV is a highly variable virus that easily mutates. This means there can be many different strains of HIV, even within the body of a single infected person. As an example, within HIV-1 Group M Subtype B there may be many strains that vary slightly but are still genetically similar enough to be classified as Subtype B viruses. It is even possible for 2 or more subtypes to combine and form a hybrid, known as a CRF—circulating recombinant form (Seladi-Schulman, 2021; Ellis, 2022; Akahome, 2024).

1.5 Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS

Epidemiology is the study of how disease is distributed in populations and the factors that influence the distribution. Epidemiologists try to discover why a disease develops in some people and not in others. Clinically, AIDS was first recognized in the United States in 1981, including in the state of Washington. In 1983 HIV was discovered to be the cause of AIDS.

People who are infected with HIV come from all races, countries, sexual orientations, genders, and income levels. Globally, in 2023 there were 39.9 million people with HIV and approximately 86% of them knew their HIV status. Worldwide an estimated 1.3 million individuals acquired HIV in 2023. This is a 39% decline in new HIV infections since 2010 and a 60% decline since the peak in 1995 (HIV.gov, 2024; UNAIDS , 2024a).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that in the US in 2022 1.2 million people aged 13 years and older were living with HIV infection, and 13% were unaware of their infection. This is a decline from 25% in 2003 and 20% in 2012, and it is a positive sign because studies have shown that people with HIV who know that they are infected avoid behaviors that spread infection to others, and they can pursue medical care and treatments to improve and prolong their lives. The CDC overall goal is to increase the estimated percentage of people with HIV who have received an HIV diagnosis to at least 95% by 2025 and remain at 95% by 2030 (CDC, 2024a).

There has been continued progress in HIV prevention as shown by a steady overall 12% decline in estimated new HIV infections from 36,200 in 2018 to 31,800 in 2022. The CDC overall goal is a decrease in the estimated number of new HIV infections to 9,300 by 2025 and 3,000 by 2030 (CDC ,2024a).

Recent years’ data for HIV diagnoses—the number of people who receive an HIV diagnosis during a given year—present an interpretive issue. The overall goal is to decrease the number of new HIV diagnoses to 9,588 by 2025 and 3,000 by 2030 (CDC, 2024b). However, in the period from 2018 to 2022, diagnoses fell from 37,594 in 2018 to 36,768 in 2019 and 30,630 in 2020 only to rise in 2021 to 36,096 and in 2022 to 37,981. The data for 2020-2022 should be interpreted with caution because of the serious effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath on access to HIV testing, care, and related services, and case surveillance activities in state and local jurisdictions. In addition, the potential influence of pandemic effects on the U.S. public health system overall need to be taken into consideration (CDC, 2024c).

Through 2018 the cumulative estimated number of deaths of people with diagnosed HIV infection ever classified as stage 3 (AIDS) in the United States was approximately 700,000 (deaths may be due to any cause, which can make data interpretation complex). Worldwide, 42.3 million people have died from AIDS-related illnesses since the epidemic began. In 2023 about 630,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses, down significantly from 2.1 million in 2004 and 1.3 million in 2010 (UNAIDS, 2024).

The discovery of combination antiviral drug therapies in 1996 resulted in a dramatic decrease in the number of deaths due to AIDS among people given the drug therapies. New drug treatments have continued to be developed ever since. People respond differently to the therapies and side effects can be challenging. The medications are expensive and require strict dosing schedules. While not yet sufficient for everyone, financial assistance for drug treatments and other HIV/AIDS care is available, as is case management and mental health support. In developing countries many people with HIV do not have access to the newer drug therapies, but access is improving.

![]()

Approximately 15,000 people in Washington State are living with HIV and about 400 new cases are diagnosed every year. From 1983 to 2021 8989 HIV infected people have died, of that total 224 died in 2021 which was a mortality rate of 2.9%. The mortality rate has gone up and down between 2.1% and 2.9% during the years from 2102 to 2021 (WA DOH, 2023).

The Washington State Department of Health collects surveillance data and makes that data available on its website. In Washington State from 2010 to 2018 the incidence of HIV (new diagnoses each year) declined from 7.2 per 100,000 people in 2010 to 5.4 per 100,000 in 2018, but remained there through 2022. The percentage of clients showing viral suppression, engagement in care, and linkage to care (within 30 days of diagnosis) all increased through 2018, but linkage to care has declined by 3% into 2022. The percentage of late diagnosis cases (where initial diagnosis of HIV accompanies initial diagnosis of AIDS) has declined from 34.7% in 2010 to 25.9% in 2018.

In 2022 there were 215 new AIDS cases and 421 new HIV cases, and 119 late diagnoses, in all cases the highest numbers are in King county.

Washington State’s Black and Hispanic/Latinx communities are disproportionately affected by HIV. While Blacks are 4% of the state’s population they represent 19% of new HIV diagnoses. Hispanic/Latinx make up 13% of the state’s population while accounting for 21% of new HIV diagnoses. Neither community is receiving all the medical care and other support services they need (WA DOH, 2020; 2020a).

![]()

1.6 HIV and AIDS Cases Are Reportable in WA

The purpose of disease reporting and surveillance is to:

- Collect information about people who are infected in order to understand how to create programs that will prevent disease.

- Assure that people who are infected are referred to medical care.

- Identify people who are infected and try to stop the spread of infection.

The following people must report information to authorities (Legal Reporting Requirements, effective January 1, 2023, Chapter 246-101 WAC) (WA DOH, 2022):

1. Providers and Health Care Facilities

- Report cases of HIV and AIDS within 3 business days to your Local Health Jurisdiction.

- When possible, submit a WA State HIV/AIDS Case Report Form.

- Report Rapid Screening Tests (RST), if performed at your facility:

- Providers and facilities performing HIV infection RST (Rapid Screening Tests) shall report as a laboratory and comply with the requirements of WAC 246-101-101 through WAC 246-101-230.

2. Laboratories:

- Report within 2 business days to Washington State Department of Health (DOH), or Public Health Seattle King County (PHSKC) for labs in King County:

- Positive or indeterminate results and subsequent negative results associated with those positives or indeterminate results for the tests below:

- Antibody detection tests (including RST)

- Antigen detection tests (including RST)

- Viral culture

- All HIV nucleic acid detection (NAT or NAAT) tests:

- Qualitative and quantitative

- Detectable and undetectable

- HIV antiviral resistance testing genetic sequences

- Positive or indeterminate results and subsequent negative results associated with those positives or indeterminate results for the tests below:

- Report within 30 days to Washington State Department of Health (DOH), or Public Health Seattle King County (PHSKC) for labs in King County:

- All CD4 counts, CD4 percent, or both (patients aged thirteen or older)

- Report at least annually to Washington State Department of Health (DOH), or Public Health Seattle King County (PHSKC) for labs in King County:

- Deidentified negative screening results

3. Local Health Jurisdictions:

- Notify the Washington State Department of Health department of HIV and AIDS cases (notifiable to the local health jurisdiction):

- Within seven days of completing the investigation, or within twenty-one days of receiving the case report or laboratory report if the investigation is not complete.

- Immediately reassign cases to the department upon determining the patient who is the subject of the case is a resident of another local health jurisdiction or resides outside Washington state.

- Local Health Jurisdictions should also work with Washington State Department of Health to investigate possible HIV cases identified through laboratory data reportable to WA DOH, known as Field Investigation Reports (FIRs). Return results of investigations to WA DOH and report any cases identified from these reports using the WA State HIV/AIDS Case Report Form. (WA DOH, 2024).