4.1 Natural History of HIV Infection

A person with untreated HIV infection will experience several stages in infection. These include viral transmission, primary HIV infection, seroconversion, asymptomatic HIV infection, symptomatic HIV infection, and AIDS. These stages as sometimes called the “natural history” of disease progression and are described below. The natural history of HIV infection has been altered dramatically in developed countries because of new medications. In countries where there is no access to these medications, or in cases where people do not become aware of their HIV infection until very late, the disease progresses as described below.

Natural History of HIV Infection

- Viral transmission

- Primary HIV infection

- Seroconversion

- Asymptomatic HIV infection

- Symptomatic HIV infection

- AIDS

The first three constitute the window period.

4.1.1 Viral Transmission

Viral transmission is the initial infection with HIV. People infected with HIV may become infectious to others within 5 days. They are infectious before the onset of any symptoms, and they will remain infectious for the rest of their lives.

4.1.2 Primary HIV Infection

During the first few weeks of HIV infection, individuals have a very high level of virus (viral load) in their bloodstream. The high viral load means the individual can easily pass the virus to others. Unfortunately, during primary infection many people are unaware that they are infected.

In this stage, about half of infected people have symptoms of fever, swollen glands (in the neck, armpits, groin), rash, fatigue, and a sore throat. These symptoms, which resemble flu, go away in a few weeks, but the individual continues to be infectious to others.

It is extremely important that healthcare providers consider the diagnosis of primary HIV infection if clients engage in behaviors that put them at risk for HIV and are presenting with the above symptoms. If individuals experience these symptoms after having unprotected sex or sharing needles, they should seek medical care and tell their provider why they are concerned about HIV infection.

4.1.3 Window Period and Seroconversion

The window period begins with initial infection and continues until the virus can be detected by an HIV test. Seroconversion is the term for the point at which HIV antibodies are detectable and the window period for antibody tests ends.

4.2 Natural Course of Untreated HIV Infection

The first two weeks following infection are highly contagious but not detectable by HIV tests (see figure below). Markers of infection may begin to appear after 10 days but can take up to 12 weeks or longer to reach seroconversion. As is seen on the line curves, the viral load continues to increase until there are sufficient antibodies to suppress, but not kill, the virus. Once the antibodies become active, an untreated patient may be asymptomatic for 10 years before the antibodies are no longer able to suppress the virus and the person becomes symptomatic.

Source: Adapted from Conway & Bartlett, 2003.

4.2.1 Asymptomatic HIV Infection

Following seroconversion, a person infected with HIV is asymptomatic (has no noticeable signs or symptoms). The person may look and feel healthy but can still pass the virus to others. It is not unusual for an HIV-infected person to live 10 years or longer without any outward physical signs of progression to AIDS. Meanwhile, the person’s blood and other systems are affected by HIV, which would be reflected in laboratory tests. Unless a person in this stage has been tested for HIV, they will probably not be aware they are infected.

4.2.2 Symptomatic HIV Infection

During the symptomatic stage of HIV infection, a person begins to have noticeable physical symptoms that are related to HIV infection. Anyone who has symptoms like these and has engaged in behaviors that transmit HIV should seek medical advice. The only way to know for sure if you are infected with HIV is to take an HIV test.

Although no symptoms are specific only to HIV infection, some common symptoms are:

- Persistent low-grade fever

- Pronounced weight loss that is not due to dieting

- Persistent headaches

- Diarrhea that lasts more than 1 month

- Difficulty recovering from colds and the flu

- Being sicker than they normally would with ordinary illnesses

- Recurrent vaginal yeast infections in women

- Thrush/yeast infection coating the mouth or tongue

Apply Your Learning

Q: A client comes into your clinic complaining of a fever of 99ºF for 3 weeks, weight loss of 15 pounds in the past 2 months, and diarrhea for 6 weeks. He claims he has not changed his regular diet and is not trying to lose weight. He states he has had a lingering cold for weeks and just doesn’t feel good or have energy. What additional history and physical factors would you need to assess?

A: These are classic symptoms of an HIV infection but could also be a gastrointestinal or respiratory virus. Sexual history, diet history, and family history of GI diseases would need to be assessed. A chest x-ray, CBC, basic metabolic panel, and thyroid levels should be ordered to rule out pneumonia, infections, thyroid health, and inflammatory conditions. It is said as high as 90% of a diagnosis can be determined by a thorough history alone.

4.2.3 AIDS

Did You Know. . .

An AIDS diagnosis can only be made by a licensed healthcare provider and, once the diagnosis is made, the person is always considered to have AIDS.

An AIDS diagnosis is based on the result of HIV-specific blood tests and/or on the person’s physical condition. Established AIDS-defining illnesses, white blood cell counts, and other conditions are specifically linked to making an AIDS diagnosis. Once a person is diagnosed with AIDS, even if they later feel better, they do not “go backwards” in the classification system for HIV infection. They are always considered to have AIDS.

People who have an AIDS diagnosis may often appear to a casual observer to be quite healthy, but they continue to be infectious and can pass the virus to others. Over time, people with AIDS frequently have a reduced white blood count and develop poorer health. They may also have a significant amount of virus present in their blood, measurable as viral load.

4.2.4 Cofactors

A cofactor is a separate condition that can change or speed up the course of disease. There are several cofactors that can increase the rate of progression to AIDS. They include a person’s age, certain genetic factors, and possibly drug use, smoking, nutrition, and HCV.

4.2.5 Time from Infection to Death

If the infection is untreated, the average time from HIV infection to death is 10 to 12 years. Early detection and continuing medical treatment have been shown to prolong life for many more years.

4.3 AIDS Surveillance Case Definition

[This section was taken from CDC, 2014.]

Following extensive consultation and peer review, the CDC and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists have revised and combined the surveillance case definitions for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection into a single case definition for people of all ages, which includes adults and adolescents aged ≥13 years and children aged <13 years. The revisions were made to address multiple issues, the most important of which was the need to adapt to recent changes in diagnostic criteria.

Laboratory criteria for defining a confirmed case now accommodate new multi-test algorithms, including criteria for differentiating between HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection and for recognizing early HIV infection. A confirmed case can be classified in one of five HIV infection stages: 0, 1, 2, 3, or unknown.

Early infection, recognized by a negative HIV test within 6 months of HIV diagnosis, is classified as stage 0, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is classified as stage 3. Criteria for stage 3 have been simplified by eliminating the need to differentiate between definitive and presumptive diagnoses of opportunistic illnesses.

Clinical (non-laboratory) criteria for defining a case for surveillance purposes have been made more practical by eliminating the requirement for information about laboratory tests. The surveillance case definition is intended primarily for monitoring the HIV infection burden and planning for prevention and care on a population level, not as a basis for clinical decisions for individual patients (CDC, 2014).

Since the first cases of AIDS were reported in the United States in 1981, surveillance case definitions for HIV infection and AIDS have undergone several revisions to respond to diagnostic advances. This new document updates the surveillance case definitions originally published in 2008. It addresses multiple issues, the most important of which was the need to adapt to recent changes in diagnostic criteria.

Other needs that prompted the revision included:

- Recognition of early HIV infection

- Differentiation between HIV-1 and HIV-2 infections

- Consolidation of staging systems for adults/adolescents and children

- Simplification of criteria for opportunistic illnesses indicative of AIDS,

- Revision of criteria for reporting diagnoses without laboratory evidence (CDC, 2014)

Stage 3–Defining Opportunistic Illnesses in HIV Infection

- Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent*

- Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs

- Candidiasis of esophagus

- Cervical cancer, invasive†

- Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary

- Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (>1 month's duration)

- Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes), onset at age >1 month

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision)

- Encephalopathy attributed to HIV§

- Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (>1 month's duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis (onset at age >1 month)

- Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 month's duration)

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Lymphoma, Burkitt (or equivalent term)

- Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term)

- Lymphoma, primary, of brain

- Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis of any site, pulmonary†, disseminated, or extrapulmonary

- Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously known as “Pneumocystis carinii”) pneumonia

- Pneumonia, recurrent†

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Salmonella septicemia, recurrent

- Toxoplasmosis of brain, onset at age >1 month

- Wasting syndrome attributed to HIV

* Only among children aged <6 years.

† Only among adults, adolescents, and children aged ≥6 years.

Source: CDC, 2014.

4.3.1 Clinical Manifestations vs. Opportunistic Infections

When their immune system is suppressed, people have weaker defenses against the wide variety of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other pathogens that are present almost everywhere. A clinical manifestation is the physical result of some type of illness or infection.

The opportunistic infections associated with HIV include any of the infections that are part of an AIDS-defining classification. For example, the opportunistic infection cytomegalovirus often causes the clinical manifestation of blindness in people with AIDS.

4.4 HIV in the Body

Scientists are always learning new information about how HIV affects the body. It is well known that HIV infection causes a gradual, pronounced decline in the immune system’s functioning. People with HIV are at risk for a wide variety of illnesses, both common and exotic.

HIV affects the kind and number of blood cells, fat and muscle distribution, and the body’s metabolism and immune system. It can also affect the structure and function of the brain, causing confusion or dementia.

Opportunistic infections, as well as painful or uncomfortable conditions caused by HIV include:

- Thrush (yeast infections in the mouth)

- Chronic pneumonias, sinusitis, or bronchitis

- Diarrhea, nausea or vomiting

- Fatigue, weakness, weight loss, fever

- Painful joints, muscles, or nerve pain

- Urinary or fecal incontinence

- Vision or hearing loss

4.4.1 HIV in Children

[https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/hiv-and-children]

According to the CDC, 53 cases of HIV in children younger than 13 years of age were diagnosed in the United States and 6 dependent areas in 2021. This is less than half of the 105 cases of HIV reported in this age group in 2017. From 2017 through 2020 in the United States and Puerto Rico, 12,569 children born were exposed but did not perinatally acquire HIV.

HIV can pass from a birthing parent with HIV to their child during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding, called perinatal transmission of HIV (also called mother-to-child transmission). In the United States, this is the most common way children under 13 years of age get HIV.

The use of HIV medicines and other strategies have helped to lower the rate of perinatal transmission of HIV to 1% or less in the United States and Europe.

Treatment with HIV medicines (ART) is recommended for everyone with HIV, including children. HIV medicines help people with HIV live long, healthy lives and reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

Several factors affect HIV treatment in children, including a child’s growth and development. For example, because children grow at different rates, dosing of an HIV medicine may depend on a child’s weight rather than their age. Children who are too young to swallow a pill may use HIV medicines that come in liquid form.

Issues that make it difficult to take HIV medicines every day and exactly as prescribed (called medication adherence) can affect HIV treatment in children. Effective HIV treatment depends on good medication adherence.

Did You Know. . .

Women with HIV who take antiretroviral medication during pregnancy as recommended can reduce the risk of transmitting HIV to their babies to less than 1%.

![]()

In Washington State children with HIV may benefit from the Children with Special Health Care Needs program. Care coordinators for this program are located at every county health department or district. Local community-based organizations like the Northwest Family Center in Seattle, and specialty hospitals like Children’s Medical Center in Seattle and Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital in Tacoma, may provide additional support to children and families.

4.4.2 HIV in Women

[https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/hiv-and-women-based-assigned-sex-birth]

HIV diagnoses decreased 6% among women overall from 2015 to 2019. Although trends varied for different groups of women, HIV diagnoses declined for groups most affected by HIV, including Black/African American women and young women aged 13 to 24.

Treatment with HIV medicines (called antiretroviral therapy or ART) is recommended for everyone with HIV. Treatment with HIV medicines helps people with HIV live long, healthy lives. ART also reduces the risk of HIV transmission.

People should start taking HIV medicines as soon as possible after HIV is diagnosed. However, birth control and pregnancy are two issues that can affect HIV treatment in women.

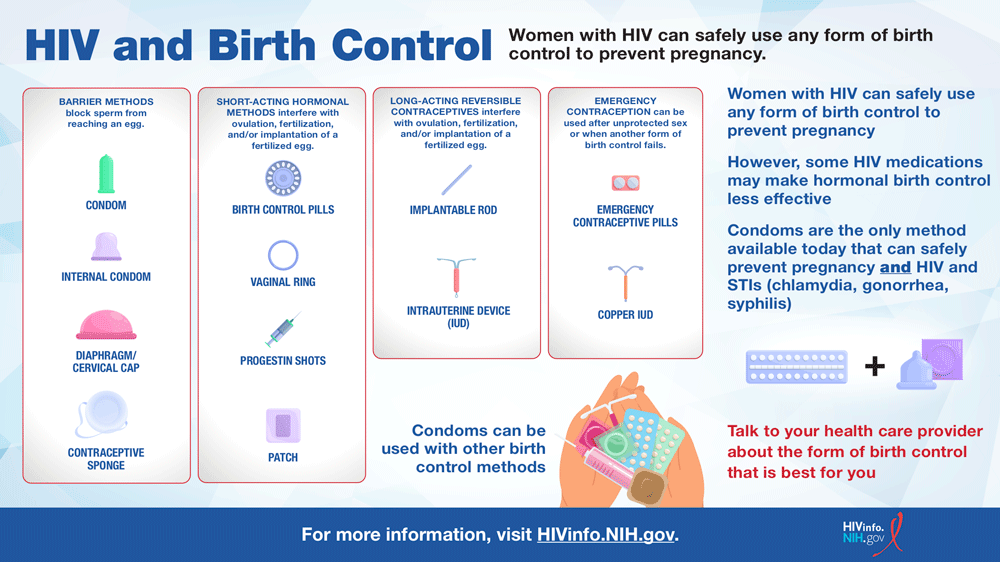

Birth Control

Some HIV medicines may reduce the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives, such as birth control pills, patches, rings, or implants. Women taking certain HIV medicines may have to use an additional or different form of birth control. The good news is that all forms of birth control are safe for women with HIV to use (hivinfo.nih.gov, n.d.).

Source: https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/infographics/hiv-and-birth-control

Pregnancy

Women with HIV take HIV medicines during pregnancy and childbirth to reduce the risk of perinatal transmission of HIV and to protect their own health.

The choice of an HIV treatment regimen to use during pregnancy depends on several factors, including a woman’s current or past use of HIV medicines, other medical conditions she may have, and the results of drug-resistance testing. In general, pregnant women with HIV can use the same HIV treatment regimens recommended for non-pregnant adults—unless the risk of any known side effects to a pregnant woman or her baby outweighs the benefits of a regimen.

Sometimes a woman’s HIV treatment regimen may change during pregnancy. Women and their health care providers should discuss whether any changes need to be made to an HIV treatment regimen during pregnancy.

PrEP and PEP for Women

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is HIV medicine taken to reduce the chances of getting HIV infection. PrEP is used by people who do not have HIV but are at high risk of being exposed to HIV through sex or injection drug use.

There are two PrEP medications approved for use by women and other people who may have receptive vaginal sex (such as some transgender men or nonbinary people):

- Truvada (or a generic equivalent), a pill that is taken by mouth every day.

- Apretude, a shot that is taken every 2 months.

In emergency situations, people can also take post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). PEP is HIV medicine taken within 72 hours (3 days) to reduce the chances of getting HIV infection after a possible exposure to HIV.

Women should speak with their health care provider to learn about PrEP and PEP and how to protect themselves from HIV.

4.4.3 Access to Medical Care

As the medications that are available to treat HIV infection have become more numerous and complex, HIV care has become a medical specialty. If possible, people who have HIV infection should seek out a physician who is skilled in the treatment of HIV and AIDS. The American Academy of HIV Medicine maintains a referral directory on its website here: https://aahivm.org. Referral directory is here: https://providers.aahivm.org/referral-link-search].

![]()

People in Washington State may gain access to an HIV specialist through the assistance of the case manager(s) in their county. Call your local health department or health district for information on case management programs.

4.5 Impact of New Drugs on Clinical Progression

Did You Know. . .

People with HIV who take HIV medicine as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load (or stay virally suppressed) won’t transmit HIV to their sexual partners.

Before 1996 there were three medications available to treat HIV. These drugs were used singly and were of limited benefit. Researchers in 1996 discovered that taking combinations of these and newer medications dramatically reduced the amount of HIV (viral load) in the bloodstream of a person infected with HIV. Two or three different medications were used in combination, each one targeting a separate part of the virus and its replication. The reduction of deaths from AIDS in the United States has been primarily attributed to this combination therapy. Originally known as highly active antiretroviral therapy or HAART, this treatment is simply referred to now as ART (antiretroviral therapy).

4.5.1 ART (Antiretroviral therapy)

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is recommended for all people with HIV, regardless of CD4 cell count. It should be started as soon as possible after diagnosis and should be accompanied by patient education regarding the benefits and risks of ART and the importance of adhering to ART. People with HIV who are aware of their status should be prescribed ART and, by achieving and maintaining an undetectable (<200 copies/mL) viral load, can remain healthy for many years.

ART is available globally and the number of people with access to it is increasing every year. In 2023, of the nearly 40 million people with HIV, 30.7 million of them were on ART (Benisek, 2024).

ART reduces HIV-related morbidity and mortality at all stages of HIV infection and reduces HIV transmission. ART is known to reduce levels of multiple markers of immune activation and inflammation. Mortality associated with uncontrolled HIV replication at higher CD4 counts is believed to be due to immune activation and an inflammatory milieu that promotes progression of end-organ disease.

In the large, multinational Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) study, asymptomatic patients with HIV infection who started ART immediately after diagnosis had a >50% reduction in morbidity and mortality compared with patients who deferred treatment until they had a CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm.

ART reduces the chances of transmitting HIV to others. Three landmark studies have shown that treatment prevents sexual transmission of HIV. Evidence shows that taking ART as prescribed can help achieve an undetectable viral load. When maintained, an undetectable viral load prevents transmission of HIV through sex. This is known as treatment as prevention.

Treatment Types

All people with HIV should take HIV treatment, no matter how long they've had HIV or how healthy they are. If you delay treatment, HIV will continue to harm your immune system and increase your chances of transmitting HIV to others, getting sick, and developing AIDS.

There are two types of HIV treatment: pills and shots.

Pills are recommended for people just starting HIV treatment. There are many FDA-approved single pill and combination medicines available.

HIV treatment shots are long-acting injections given once a month or once every other month, depending on your treatment plan.

Shots may be right for you if you are an adult with HIV who

- has had an undetectable viral load (or has achieved viral suppression) for at least three months,

- has no history of treatment failure, and

- has no known allergy to the medicines in the shot.

You’ll need to visit your provider regularly to receive your shots. Tell your health care provider as soon as possible if you've missed or plan to miss an appointment for your shot.

4.5.2 Drug Resistance

Did You Know. . .

Viral load suppression – the goal of HIV treatment – significantly contributes to preventing the emergence of HIV drug resistance. When viral load suppression is achieved and maintained, drug-resistant HIV is less likely to emerge (WHO, 2024).

With so many people on HIV medications, drug resistance has been increasing. HIV drug resistance can be either acquired or transmitted. Transmitted drug resistance means that the virus that originally infected the person was already drug resistant. The prevalence of this type is 9.3%. Acquired drug resistance can happen for several reasons. One is if a person does not take their medications consistently according to instructions, allowing the virus to replicate at the same time. Another is when a person’s body does not absorb the drugs properly or other drugs the person is taking interfere with the HIV medications.

There is a third type of resistance known as pretreatment HIV drug resistance. This is not common but can happen as a result of a baby being given drugs to prevent perinatal transmission who becomes infected anyway, or when a patient was taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV but still became infected.

If a patient is drug resistant, testing can be done to gather information to determine adjustments to be made. Two types of tests are used: Genotype testing and Phenotype testing. Persons with HIV infection need to work closely with their medical providers to manage their treatment (Benisek, 2024; WHO 2024).

4.5.3 Side Effects

As with most medications, HIV medications can have side effects. Most of these are manageable and do not cause serious problems, but some can be serious. Overall, the benefits of FDA-approved HIV medicines far outweigh the risk of side effects. In addition, HIV medicines have been improved over the years to cause fewer side effects, making people less likely to have side effects from HIV medicines (HIVinfo.nih.gov, 2024).

Common side effects the may last only a few days or weeks include nausea, fatigue, and sleep problems. Other side effects may take months or even years to became apparent. High cholesterol—a major risk factor for heart disease—is one of them. If a person is taking drugs to manage another medical condition there is always the possibility of drug interaction problems. Patients can use the Drug Database at HIV.gov (https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/drugs) to research their HIV medications as well as anything else they are taking for side effects and potential interactions.

While it may become necessary to change an HIV medication due to a side effect, it is important to remember NOT to cut down on, skip, or stop taking ones HIV medicines unless directed to by your health care provider (HIVinfo.nih.gov, 2024).

4.5.4 Complementary Therapies

People have relied on complementary therapies to treat HIV infection for as long as HIV has been known. Many people use these treatments along with therapies from their medical provider. Others choose to use only complementary therapies.

These therapies comprise a wide range of treatments, including vitamins, massage, herbs, naturopathic remedies, and many more. While there is no evidence of harm from these treatments, there is also very little evidence of benefit. Many of these remedies still have not been studied to see if they help.

It is important for people who are taking complementary therapies to share this information with their medical provider. There may be harmful side effects from the interactions of the “natural” medicine and antiretrovirals. For example, St. John’s Wort is an herbal remedy often used for depression that interacts negatively with HIV medications.

Some substances, including prescription and over the counter (OTC) medications and street drugs, may have serious interactions with antiretroviral medications. It is extremely important that people on HIV medications tell their healthcare providers doctor about all other drugs they are taking.

4.5.5 Case Management

People living with HIV often seek the assistance of an HIV case manager who can help explain the different types of services available. Most states have systems in place to provide prescription and medical assistance to people living with HIV and AIDS. Contact your local health department or district to find case management in your community.

![]()

You can also call the Washington State DOH Client Services toll-free at 877 376 9316. Children with HIV may also benefit from the Children with Special Health Care Needs program.

4.5.6 Prevention Strategies

There are now more options than ever before to reduce the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. Using medicines to treat HIV, using medicines to prevent HIV, using condoms, having only low-risk sex, only having partners with the same HIV status, and not having sex can all effectively reduce risk. Some options are more effective than others. Combining prevention strategies may be even more effective. But in order for any option to work, it must be used correctly and consistently (CDC, 2022).

Elements of HIV Prevention includes:

- Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

- Treatment as Prevention

- Condoms

- Medical Male Circumcision

The six prevention strategies above have undergone significant study and their effectiveness in some or many situations has been demonstrated and details are available on the CDC website (CDC, 2022). As noted throughout this class all of the following have a role in HIV prevention in many scenarios.

- HIV Testing/Counseling

- Education/Behavior Modification

- STI Treatment

- Blood Supply Screening

- Microbicides

- Treatment/Prevention of Drug/Alcohol Abuse

- Clean Syringes

No one prevention option works all the time with every target group, but each one has shown, and continues to show, frequent measurable success with many groups. Used together, they have made significant headway against HIV.

4.5.7 Treatment as Prevention

People with HIV should take medicine to treat HIV as soon as possible. HIV medicine is called antiretroviral therapy, or ART. If taken as prescribed, HIV medicine reduces the amount of HIV in the body (viral load) to a very low level, which keeps the immune system working and prevents illness. This is called viral suppression—defined as having less than 200 copies of HIV per milliliter of blood. HIV medicine can even make the viral load so low that a test can’t detect it. This is called an undetectable viral load.

Getting and keeping an undetectable viral load is the best thing people with HIV can do to stay healthy. Another benefit of reducing the amount of virus in the body is that it prevents transmission to others through sex or syringe sharing, and from mother to child during pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding. This is sometimes referred to as treatment as prevention. There is strong evidence about treatment as prevention for some of the ways HIV can be transmitted, but more research is needed for other ways (CDC, 2023).

HIV Transmission Risk With Undetectable Viral Load by Transmission Category | |

|---|---|

Transmission Category | Risk for People Who Keep an Undetectable Viral Load |

Sex (oral, anal, or vaginal) | Studies have shown no risk of transmission |

Pregnancy, labor, and delivery | 1% or less† |

Sharing syringes or other drug injection equipment | Unknown, but likely reduced risk |

Breastfeeding | Substantially reduces but does not eliminate risk. |

† The risk of transmitting HIV to the baby can be 1% or less if the pregnant person takes HIV medicine daily as prescribed throughout pregnancy, labor, and delivery and gives HIV medicine to their baby for 4-6 weeks after giving birth.

As a concept and a strategy, treating HIV-infected people to improve their health and to reduce the risk of onward transmission—sometimes called treatment as prevention—refers to the personal and public health benefits of using ART to continuously suppress HIV viral load in the blood and genital fluids, which decreases the risk of transmitting the virus to others. The practice has been used since the mid-1990s to prevent mother-to-child, or perinatal, transmission of the virus.

Treatment alone won’t solve the global HIV epidemic, but it is an important element of a multi-pronged attack that includes prevention efforts, wise investment of resources, greater access to screening and medical care, and involvement by everyone—local, state, and federal government; faith-based communities; and private groups and individuals. Providing treatment for people who are living with HIV infection must be the first priority and, in order to get treatment, one must be aware of the need. Thus, testing and identification of those with HIV infection becomes the critical entry point into the medical care system for both treatment and prevention.

4.5.8 Vaccine

There is currently no vaccine available that will prevent HIV infection. However, scientists around the world, with support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), are working to develop one. Work on an HIV vaccine can be traced back three decades to before the first HIV vaccine clinical trial at the National Institutes of Health in 1987. Discouraging as that timeframe may sound, it takes a great deal of time to do the work needed to create a vaccine, and HIV provides some unique challenges (NIAID, 2024, 2014; HIV.gov, 2024a).

Vaccines historically have been the most effective means to prevent and even eradicate infectious diseases. Like smallpox and polio vaccines, a preventive HIV vaccine could save millions of lives. Developing safe, effective, and affordable vaccines that can prevent HIV infection in uninfected people is the best hope for controlling and/or ending the HIV epidemic.

The long-term goal is to develop a safe and effective vaccine that protects people worldwide from getting infected with HIV. However, even if a vaccine only protects some people, it could still have a major impact on the rates of transmission and help control the epidemic, particularly for populations where there is a high rate of HIV transmission. A partially effective vaccine could decrease the number of people who get infected with HIV, further reducing the number of people who can pass the virus on to others.

HIV is a very complex, highly changeable virus, and it is different from other viruses because the human immune system never fully gets rid of it. Most people who are infected with a virus, even a deadly one, recover from the infection, and their immune systems clear the virus from their bodies. Once cleared, an immunity to the virus often develops. But humans do not seem to be able to fully clear HIV and develop immunity to it. The body cannot make effective antibodies and HIV actually targets, invades, and then destroys important cells that the human body needs to fight disease. So far, no person with an established HIV infection has cleared the virus naturally, and this has made it more difficult to develop a preventive HIV vaccine.

Scientists continue to develop and test vaccines in labs, in animals, and even in human subjects. Trials allow researchers to test the efficacy and safety of their vaccine candidate, and each trial has yielded important information on the path to developing a widely effective vaccine, but there are still many challenges to be overcome.

4.5.9 Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP) is medicine taken to prevent getting HIV and it is highly effective for preventing HIV when taken as prescribed.

- PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99%.

- PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from injection drug use by at least 74%.

PrEP is less effective when not taken as prescribed. Since PrEP only protects against HIV, condom use is still important for protection against other STDs. Condom use is also important to help prevent HIV if PrEP is not taken as prescribed.

PrEP is for adults and adolescents without HIV who may be exposed to HIV through sex or injection drug use. PrEP may be an option to help protect pregnant people and their babies from getting HIV while trying to get pregnant, during pregnancy, or while breastfeeding.

Three FDA-approved PrEP medications are available. Two consist of a combination of drugs in a single oral tablet taken daily. The third is a medication given by injection every 2 months.

- Emtricitabine (F) 200 mg in combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg (F/TDF—brand name Truvada® or generic equivalent).

- Emtricitabine (F) 200 mg in combination with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) 25 mg (F/TAF—brand name Descovy®).

- Cabotegravir (CAB) 600 mg injection (brand name Apretude®).

PrEP is safe to take. Some people experience side effects like diarrhea, nausea, headache, fatigue, and stomach pain. These side effects usually go away over time. However, patients need to work with their health care provider about any side effects that are severe or do not go away.

There are no known interactions between PrEP and hormone-based birth control methods, e.g., the pill, patch, ring, shot, implant, or IUD. It is safe to use both at the same time. There are no known drug conflicts between PrEP and hormone therapy. It is safe to use both at the same time.

PrEP can help protect you if you don’t have HIV and any of the following apply to you:

You have had anal or vaginal sex in the past 6 months and you

- have a sexual partner with HIV (especially if the partner has an unknown or detectable viral load),

- have not consistently used a condom, or

- have been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease in the past 6 months.

You inject drugs and you

- have an injection partner with HIV, or

- share needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment (for example, cookers).

You have been prescribed PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) and you

- report continued risk behavior, or

- have used multiple courses of PEP.

You may choose to take PrEP, even if the behaviors listed above don’t apply to you.

Most insurance plans and state Medicaid programs cover PrEP. Under the Affordable Care Act, PrEP must be free under almost all health insurance plans. That means you can't be charged for your medication, clinic visits, and lab tests needed to maintain your prescription. If you don't have insurance or Medicaid coverage, there are other programs that provide PrEP for free or at a reduced cost.

Before starting PrEP, you must take an HIV test to make sure you don't have HIV. While taking PrEP, you'll have to visit your health care provider routinely as recommended for follow-up visits, HIV tests, and prescription refills or shots.

You must take PrEP as prescribed for it to work. If you do not take PrEP as prescribed, there may not be enough medicine in your bloodstream to block the virus. The right amount of medicine in your bloodstream can stop HIV from taking hold and spreading in your body.

There are several reasons why people stop taking PrEP. Talk to your health care provider if you're thinking about stopping PrEP. They'll discuss how to stop PrEP safely and suggest other HIV prevention methods that may work better for you (CDC, 2024j, 2024k).

The CDC maintains PrEPline (1-855-448-7737) to provide expert guidance to health care providers on considerations for providing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to people who don’t have HIV as part of an HIV prevention program.

4.6 Tuberculosis, Other STDs, and Hepatitis B and C

Because of the interrelationships between HIV, tuberculosis (TB), sexually transmitted diseases, HBV, and HCV, a brief discussion of each requires review by health care professionals.

4.6.1 Tuberculosis and HIV

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) is transmitted by airborne droplets from people with active pulmonary or laryngeal TB during coughing, sneezing, or talking. Although TB bacteria can live anywhere in the body, infectious pulmonary or laryngeal TB poses the greatest threat to public health.

Inactive TB (latent TB infection), which is asymptomatic and not infectious, can last for a lifetime. A presumptive diagnosis of active TB disease is made when there are positive test results or acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in sputum or other bodily fluids. The diagnosis is confirmed by identification of M. tuberculosis on culture, which should be followed by drug sensitivity testing of the bacteria. If not treated properly, active TB disease can fatal.

TB Epidemiology

Tuberculosis is one of the world’s leading infectious disease killers. CDC estimates up to 13 million people in the United States live with inactive TB (CDC, 2024m). Nearly 2 billion people—one quarter of the world's population—may be infected with TB and 10.6 million became ill with TB disease in 2022. TB is the #1 cause of death among people living with HIV and whose weakened immune systems make them more susceptible to TB disease (CDC, 2024n, 2024p).

Worldwide in 2023 an estimated 10.8 million people became ill with TB, and a total of 1.25 million people died from TB, including 161,000 people with HIV. TB is present in all countries and affects people in all age groups. The WHO estimates that 79,000 lives have been saved by actions to combat TB since 2000 (WHO, 2024b).

In 2022, 8,331 TB disease cases were reported in the United States, which is a case rate of 2.5 cases/100,000. In 2021 (the latest data available) there were 602 TB-related deaths. Four states—California, Texas, New York, and Florida—account for half of all U.S. cases (CDC, 2022a).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, TB case counts and incidence rates had been steadily decreasing in the United States since the 1992 TB resurgence peak. During 2020, TB case counts and incidence rates declined substantially, likely because of factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, TB case counts and incidence partially rebounded but remained lower compared with 2019. In 2022, reported TB cases and incidence rates increased for the second year in a row, but remained lower compared with 2019 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. (CDC, 2024m).

![]()

In its Communicable Disease Report 2022, the Washington State Department of Health notes that there were 251 reported new cases of TB reported in 2022. Over the previous ten years the incidence rate has been downward overall with significant increases in 2021 and 2022, mirroring the US situation noted above. From 2018 to 2022 there were between 6 and 10 TB-related deaths per year (WDOH, 2024a).

In 2022 4 of 39 counties had 10 or more cases. These six counties represent 72.1% of the reported cases and 44% of the total were in King County (WDOH, 2024a; King County, 2022).

Transmission and Progression

When infectious secretions sneezed or coughed by an adult with pulmonary TB are breathed in by another person, the bacteria may come to rest in the lungs. After several weeks the bacteria multiply, and some asymptomatic, pneumonia-like symptoms may occur. The TB bacteria are carried through the bloodstream and lymph system, pumped through the heart, and then disseminated through the body.

The largest amount of bacteria goes to the lungs. In most cases, this process, called primary infection, resolves by itself and something called delayed-type hypersensitivity is established. This is measured with the tuberculin skin test. The incubation period for this primary infection is 2 to 10 weeks. In most cases, a latent state of TB develops. Ninety percent of people with inactive TB (latent TB infection) never experience subsequent disease. Other than a positive tuberculin skin test, people with latent TB infection have no clinical, radiographic (x-ray), or laboratory evidence of TB and cannot transmit TB to others. However, people with inactive TB still need to receive treatment to prevent development of active TB disease.

Among the other 10% of infected individuals, the TB infection undergoes reactivation at some time, and they develop active TB. About 5% of newly infected people reactivate within the first 2 years of primary infection and another 5% will do so at some point later in life.

TB Symptoms

The period from initial exposure to conversion of the tuberculin skin test is 4 to 12 weeks. During this period, the patient shows no symptoms. The progression to active disease and symptoms (such as cough, chest pain, coughing up blood, weakness or fatigue, weight loss, loss of appetite, chills, fever, and night sweats) usually occurs within the first 2 years after infection but may occur at any time.

TB Prevention and Treatment

It is important to recognize the behavioral barriers to TB management, which include deficiencies in treatment regimens, poor client adherence to TB medications, and lack of public awareness. Primary healthcare providers need adequate training in screening, diagnosis, treatment, counseling, and contact tracing for TB through continuing education programs and expert consultation.

Promoting patient adherence to the sometimes-complicated medication schedule also requires consideration of patients’ cultural and ethnic perceptions of their health condition. Providing strategies and services that address the multiple health problems associated with TB (such as alcohol and drug abuse, homelessness, and mental illness) also builds trust and promotes adherence to treatment plans.

There are several safe and effective treatment plans recommended in the United States for inactive TB and active TB disease. A treatment plan (also called treatment regimen) for inactive TB or active TB disease is a schedule to take TB medicines to kill all the TB germs. A treatment plan for inactive TB or active TB disease will include:

- The types of TB medicines to take,

- How much TB medicine to take,

- How often to take the TB medicines,

- How long to take the medicines,

- How to monitor yourself for any side effects of your TB medicine, and

- The health care provider(s) who will support you through the treatment process.

You and your health care provider will discuss which treatment plan is best for you.

Inactive TB

Treatment for inactive TB can take three, four, six, or nine months depending on the treatment plan.

The treatment plans for inactive TB use different combinations of medicines that may include:

- Isoniazid

- Rifampin

- Rifapentine

Active TB disease

Treatment for active TB disease can take four, six, or nine months depending on the treatment plan.

The treatment plans for active TB disease use different combinations of medicines that may include:

- Ethambutol

- Isoniazid

- Moxifloxacin

- Rifampin

- Rifapentine

- Pyrazinamide

![]()

Current recommendations can be found in the Washington State Department of Health’s TB Services and Standards Manual, updated in 2023, which outlines how public health staff complete TB control tasks in Washington State and is available from the department online.

TB/HIV Co-Infection

People co-infected with HIV/TB are at considerably greater risk of developing TB disease than those with TB alone. Studies suggest that the risk of developing TB disease is 7% to 10% each year for people who are infected with both M. tuberculosis and HIV, whereas it is 10% over a lifetime for a person infected only with M. tuberculosis.

In an HIV-infected person, TB disease can develop in either of two ways. A person who already has latent TB infection can become infected with HIV, and then TB disease can develop as the immune system is weakened. Or, a person who has HIV infection can become infected with M. tuberculosis, and TB disease can then rapidly develop because the immune system is not functioning well.

Persons with HIV should be tested for TB and receive treatment regardless of the type of TB they have.

![]()

Any HIV-infected person with a diagnosis of TB disease should be reported as having TB and AIDS. For more information on TB, contact the:

- Communicable disease staff in each county health department/district

- Washington State Department of Health TB program, (206) 418-5500

4.6.2 Other STDs and HIV

The term STD (sexually transmitted disease) refers to more than twenty-five infectious organisms transmitted through sexual activity and dozens of clinical syndromes that they cause. Sexually transmitted diseases affect men and women and can be transmitted from mothers to babies during pregnancy and childbirth. They are also called sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Bacterial, Viral, and Other Causes of STD

Bacteria cause STDs including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. Viruses cause herpes, genital warts, hepatitis B, and HIV. Scabies are caused by mites, and pubic lice cause “crabs.” Trichomoniasis is caused by tiny organisms called protozoa and “yeast” infections are caused by fungi. Some STDs, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, can have more than one cause, for example, a woman may have both gonorrhea and chlamydia, causing PID. A man may have more than one cause for epididymitis, usually gonorrhea and chlamydia. Non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) is usually caused by bacteria.

STD, Nationally and Internationally

Since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, researchers have noted the strong association between HIV and other STDs.

In 2023, over 2.4 million cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia were diagnosed and reported. This includes over 209,000 cases of syphilis, over 600,000 cases of gonorrhea, and over 1.6 million cases of chlamydia. Importantly, the combined count includes 3,882 cases of congenital syphilis, including 279 congenital syphilis stillbirths and neonatal/infant deaths. The number of STIs decreased 1.8% from 2022 to 2023, reflecting decreases in gonorrhea (7.2% decrease), stable trends in chlamydia (<1.0% change), and an increase in total syphilis (all stages and congenital syphilis combined) (1.0% increase).

As in past years, there were significant disparities in reported STIs. In 2023, almost half (48.2%) of reported cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis (all stages) were among adolescents and young adults aged 15–24 years. Additionally, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionally impacted by STIs, including gonorrhea and primary and secondary (P&S) syphilis, and co-infection with HIV is common; in 2023, 37.2% of MSM with P&S syphilis were men diagnosed with HIV (CDC, 2024s).

Globally, more than 1 million people 15-49 years of age acquire a curable sexually transmitted infection (STI) every day. The term STI is often used to reflect the fact that a person may be infected yet show no symptoms of disease. In 2020 there were an estimated 374 million new infections of chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and trichomoniasis. Drug resistance presents a major challenge to fighting these diseases worldwide (WHO, 2024a).

Primary STD infections may cause pregnancy-related complications, congenital infections, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, and cancers. STDs can also accelerate other infections like HIV.

HIV and STDs

The presence of infection with other STDs increases the risk of HIV transmission because STDs like syphilis and symptomatic herpes can cause breaks in the skin, which provide direct entry for HIV.

Inflammation from STDs such as chlamydia also makes it easier for HIV to enter and infect the body. Inflammation appears to increase HIV viral shedding and the viral load in genital secretions.

Pus or other discharge from genital ulcers from HIV-infected men and women can contain HIV. Also, sores can easily bleed and come into contact with vaginal, cervical, oral, urethral, and rectal tissues during sex.

STD Transmission and Symptoms

STDs are transmitted in the same way that HIV is transmitted: by anal, vaginal, and oral sex. In addition, skin-to-skin contact is important for the transmission of herpes, genital warts, and HPV infection, syphilis, scabies, and pubic lice.

In the past there was a great emphasis on symptoms as indicators of STD infection. We now know that 80% of those with chlamydia, 70% of those with herpes, and a great percentage of those with other STDs have no symptoms but can still infect others.

Along with prompt testing and treatment for those who do have symptoms, the emphasis in the U.S. is on screening for infection based on behavioral risk. Patients cannot assume that their healthcare providers do STD testing. In other words, women who are getting a Pap test or yearly exam should not just assume that they are also being tested for chlamydia or any other STD.

STD Prevention

Infection with an STD can be reduced or even prevented by consistently using safe sex practices. This can include abstaining from sexual activity or being in a mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner.

Prevention includes learning the right way to use condoms and using them consistently every time you have sex. Talking about the correct use of condoms with all sex partners is critically important. Additionally:

- Remember that birth control pills and shots do not prevent infections.

- Use condoms along with other birth control methods.

- Get tested (along with your sex partner).

- Avoid douching before or after sex.

- Treat STDs if they occur.

STD Tests and Treatment

Depending on the infection, tests for STDs/STIs may use blood, urine, swabs, and fluid, and some may also utilize physical exams and Pap smears. It is vital that women get Pap tests, and that both men and women disclose a history of STD during medical workups.

The CDC recommends annual testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia in sexually active women younger than 25 and those over 25 with certain risk factors. Pregnant people should be tested for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B and C early in pregnancy and those at risk for chlamydia and gonorrhea as well. Repeat testing later in pregnancy may be warranted. Sexually active men who are gay or bisexual and men who have sex with men should be tested for syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV, and hepatitis C at least once a year, sometimes more often (CDC, 2024t).

Treatment for STDs is based on lab work and clinical diagnosis. Treatments vary with each disease or syndrome. Because there is developing resistance to medications for some STDs, check the latest CDC treatment guidelines.

4.6.3 Hepatitis B and HIV

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver that may be caused by many things, including viruses. Current viruses include hepatitis A (fecal/oral transmission), B, C, D, and others. Hepatitis B (HBV) is a virus that is transmitted by the blood and body fluids of an infected person.

There are approximately 10% of people with HIV co-infected with HBV. Transmission of HBV occurs in the same behaviors as becoming infected with HIV, namely unprotected sex and through blood transmission of sharing needles.

HBV Epidemiology

In 2022 there were 2,126 new cases of acute hepatitis B reported in the U.S., leading to an estimate of 13,800 acute HBV infections during that year. In 2022 there 16,729 new cases of chronic hepatitis B reported and there were 1,797 hepatitis B-related deaths (CDC, 2024u).

About 6% to 10% of adults who have hepatitis B are considered carriers of the virus. There are up to 1.4 million carriers of HBV in the United States.

HBV is not transmitted by casual contact, breastfeeding, sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses, or through food or water. Additionally, it is not transmitted by:

- sneezing

- hugging

- coughing

Risk Factors for HBV Infection

Unvaccinated people are at higher risk for getting HBV if they share injection needles/syringes and equipment or have sexual intercourse with an infected person or with more than one partner. People who work where they come in contact with blood or body fluids, such as in a healthcare setting, prison, or home for the developmentally disabled are at higher risk than the general population.

Other people at higher risk include:

- Men who have sex with men.

- Someone who use the personal care items (razors, toothbrushes) of an infected person.

- People on kidney dialysis.

- People who were born in a part of the world with high rates of hepatitis B.

- People who receive a tattoo or body piercing with equipment contaminated with the blood from someone infected with HBV.

HBV Progression and Symptoms

The average incubation period for HBV is about 12 weeks. People are infectious when they are “hepatitis B surface-antigen positive” (HBsAg), either because they are newly infected or because they are chronic carriers.

HBV causes damage to the liver and other body systems, which can range in severity from mild, to severe, to fatal. Most people recover from their HBV infection and do not become carriers. Carriers (about 2%–6% of adults who become infected) have the virus in their body for months, years, or for life. They can infect others with HBV through their blood or other body fluid contact.

People with HBV may feel fine and look healthy although some people who are infected with HBV display mild symptoms such as loss of appetite, extreme fatigue or malaise, abdominal pain, or joint pain. Other relatively mild symptoms can include:

- Jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin)

- Dark urine

- Nausea or vomiting

- Skin rashes

Some people infected with HBV experience more severe symptoms, affecting them for weeks or months. Long-term complications can also occur, including chronic hepatitis, recurring liver disease, liver failure, and cirrhosis (chronic liver damage).

HBV Prevention and Treatment

A vaccine for HBV has been available since 1982. This vaccine is suitable for people of all ages, even infants. People who may be at risk for infection should get vaccinated. To further reduce the risk of or prevent HBV infection, a person can:

- Abstain from sexual intercourse and/or injecting drug use

- Maintain a monogamous relationship with a partner who is uninfected or vaccinated against HBV

- Use safer sex practices (as defined in the Transmission section)

- Never share needles/syringes or other injection equipment

- Never share toothbrushes, razors, nose clippers, or other personal care items that may come in contact with blood

- Use Standard Precautions with all blood and body fluids

Infants born to mothers who are HBV carriers have a greater than 90% reduction in their chance of becoming infected with HBV, if they receive a shot of hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth, plus two additional vaccine doses by age 6 months. It is vital that the women and their medical providers are aware that the woman is an HBV carrier. People with HBV should not donate blood, semen, or body organs.

There are no medications available for recently acquired (acute) HBV infection. There are antiviral drugs available for the treatment of chronic HBV infection, however treatment success varies by individual. The vaccine is not used to treat HBV once a person is infected.

4.6.4 Hepatitis C and HIV

Hepatitis C is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which is found in the blood of people who have this disease. Hepatitis C is the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States. Hepatitis C was discovered in the late 1980s, although it was likely spread for at least 40 to 50 years prior to that.

HCV Epidemiology and Transmission

Globally, 180 million people are infected with HCV. An estimated 4.1 million Americans have been infected with HCV and about 3.2 million are chronically infected (meaning they have a current or previous infection with the virus). The CDC estimates that as many as 1 million Americans were infected with HCV from blood transfusions, and that 3.75 million Americans do not know they are HCV-positive. Of these, 2.75 million people are chronically infected and are infectious for HCV.

In the United States, 8,000 to 10,000 deaths per year are attributed to HCV-associated liver disease. The number of deaths from HCV is expected to triple in the next 10 to 20 years.

![]()

An estimated 110,000 people in Washington State are infected with HCV.

HCV is transmitted primarily by blood and blood products. Blood transfusions before 1992 and the use of shared or unsterilized needles and syringes have been the main causes of the spread of HCV in the United States. The primary way that HCV is transmitted now is through injecting drug use. Since 1992 all blood for donation in the United States is tested for HCV.

Sexual transmission of HCV is considered low, but it accounts for 10% to 20% of infections. A pregnant woman who is infected with HCV, may pass the virus to her baby, but this occurs in only about 5% of those pregnancies. Household transmission is possible if people share personal care items such as razors, nail clippers, or toothbrushes.

HCV is not transmitted by:

- Breastfeeding (unless blood is present)

- Sneezing

- Hugging

- Kissing

- Coughing

- Sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses

- Food or water

- Casual contact

HCV Progression and Symptoms

The severity of HCV differs from HIV. The CDC states that, for every hundred people who are infected with HCV:

- About 15% will fully recover and have no liver damage

- 85% may develop long-term chronic infection

- 70% may develop chronic liver disease

- 20% may develop cirrhosis over a period of 20–30 years

- 1%–5% may die from chronic liver disease

People with HCV may have few or no symptoms for decades. When present, the symptoms of HCV can include:

- Nausea, stomach pain, and vomiting

- Feeling tired

- Joint pain

- Loss of appetite

- Fever

- Muscle and joint pain

- Jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin)

- Dark-colored urine or clay-colored stools

- Tenderness in the upper abdomen

HCV Prevention and Treatment

There is no vaccine to prevent HCV infection. People with HCV should not donate blood, semen, or body organs.

The following steps can protect against HCV infection:

- Follow Standard Precautions to avoid contact with blood or accidental needlesticks.

- Refrain from acquiring tattoos or skin piercings outside of a legitimate business that practices Universal Precautions.

- Refrain from any type of injecting drug use or drug equipment sharing.

- Never share toothbrushes, razors, nail clippers, or other personal care items.

- Cover cuts or sores on the skin.

- People who are HCV-infected may lower the small risk of passing HCV to their sex partner by using latex condoms and practicing safer sex.

- Women who are HCV-infected and wish to have children should discuss their choices beforehand with a medical specialist.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend treatment for all people with hepatitis C, except for pregnant people and children under 3. Most treatments involve 8–12 weeks of oral medication (pills). Treatment cures more than 95% of patients with hepatitis C, usually without side effects (CDC, 2024v).

There is no vaccine available for hepatitis C.

HCV Testing

Many people who are infected with HCV are unaware of their status. People who should consider testing are:

- Current or former injecting drug users

- People who received blood transfusions or an organ transplant prior to 1992

- Hemophiliacs who received clotting factor concentrates produced before 1987

- People who received chronic hemodialysis

- Infants born to infected mothers

- Healthcare workers who have been occupationally exposed to blood or who have had accidental needlesticks

- People who are sex partners of people with HCV

Testing for HCV is available through physicians and some health departments. In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first home test for HCV. The test kit, called Hepatitis C Check, is available from the Home Access Health Company. The test is accurate if it has been at least 6 months since the possible exposure to HCV.

HIV/HCV Co-Infection

Many people who become infected with HIV from injecting drug use are already infected with HCV. Some estimate that 15-30% of HIV-infected people in the United States are also infected with HCV. People who are co-infected with both viruses and have immune system impairment may progress faster to serious, chronic, or fatal liver damage. Most new HCV infections in the United States are among injecting drug users. The majority of hemophiliacs who received blood products contaminated with HIV also are infected with HCV.

Treating HIV in someone with HCV may be complicated because many of the medicines that are used to treat HIV may damage the liver; however, treatment for co-infection is possible in some cases with close physician supervision.

Comparison Chart of HIV, HBV, and HCV | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Transmission by | HIV | HBV | HCV |

Blood | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Semen | Yes | Yes | Rarely (more likely if blood present) |

Vaginal fluid | Yes | Yes | Rarely (more likely if blood present) |

Breast milk | Yes | No (but may be transmitted if blood is present) | No (but may be transmitted if blood is present) |

Saliva | No | No | No |

Target in the body | Immune System | Liver | Liver |

Risk of infection after needlestick exposure to infected blood | 0.5% | 1–31% | 2–3% |

Vaccine available? | No | Yes | No |

For more information on Hepatitis B or C, go to the CDC hepatitis website or call the Hepatitis Hotline at 888 443 7232 (888 4HEPCDC). | |||