The Unites States is experiencing an opioid epidemic. The New York Times reported that opioids are now the leading cause of death of Americans under the age of 50 (Katz, 2017). The 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicates approximately 9.9 million people aged 12 or older misused prescription pain relievers in the past year (SAMSHA, 2019).

Opioids include codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, meperidine, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, and heroin. Drugs of the opioids class are powerful analgesics and are used for pain management. Because they are powerful, and powerfully addicting, millions of people who use them have become physically and psychologically dependent or addicted to them. From 2000 to 2015, more than half a million people in the United States alone died from opioid drug overdoses.

Opioids are categorized as schedule 1 or 2 drugs by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). A schedule 2 drug such as morphine means that, although it has been approved for medical treatment as an analgesic, it has high potential for strong psychological and physiologic dependence. It has been used for over one hundred years as an analgesic. Heroin is made by taking morphine, which is from the opium plant, and adding a chemical reagent that makes it more potent and potentially dangerous. Heroin is a schedule 1 drug and is not approved for any medical use because it is highly addictive.

The Government Takes Notice

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies reassured the medical community that patients would not become addicted to opioid pain relievers. Healthcare providers began to prescribe them at greater rates in response to a perceived epidemic of unrelieved chronic pain. The increase of prescription opioids led to widespread misuse of both prescription and non-prescription opioids, which are in fact highly addictive despite drug manufacturers’ claims. Since the 1990s, prescription opioids have exacted an increasingly severe toll: Unintentional overdose deaths have quadrupled since 1999.

The government response to the “opioid crisis,” as it was called, has been ramping up since about 2010 ,as overdose death rates increased. In 2017, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) declared a public health emergency and announced a 5-Point Strategy To Combat the Opioid Crisis:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services.

- Target the availability and distribution of overdose-reversing drugs.

- Strengthen public health data reporting and collection.

- Support cutting-edge research on addiction and pain.

- Advance the practice of pain management. (HHS, 2017)

The federal government has taken steps to inform more judicious opioid prescribing through the development of the CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain (CDC, n.d.). Current data show that the rates of prescribing are decreasing. Between 2006 and 2017, the annual prescribing rate per 100 persons decreased from 72.4 to 58.5 for all opioids, which is an overall 19% reduction (CDC, 2019b). The declines in opioid prescribing rates since 2012 and high-dose prescribing rates since 2008 suggest that healthcare providers have become more cautious in their opioid prescribing practices. Even so, data from 2018 shows the crisis is far from over:

- More than 191 million opioid prescriptions were dispensed to American patients in 2017.

- Opioid prescription rates vary widely across states. Healthcare providers in the highest prescribing state, Alabama, wrote almost three times as many of these prescriptions per person as those in the lowest prescribing state, Hawaii.

- Studies suggest that regional variation in use of prescription opioids cannot be explained by the underlying health status of the population. (CDC, 2019b)

Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017 (67.8% of all drug overdose deaths). The opioid overdose epidemic continues to evolve and worsen because of the continuing increase in deaths involving synthetic opioids. Previously, the most common drugs involved in prescription opioid deaths were methadone, oxycodone, and hydrocodone (CDC, 2019b); however, in recent years the drugs involved in overdose deaths in the United States have changed. The rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (drugs such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol) doubled in a single year from 3.1 per 100,000 in 2015 to 6.2 in 2016, and was 9.0 deaths per 100,000 in 2017. Overdose deaths involving heroin increased from 4.1 per 100,000 in 2015 to 4.9 in 2016; it held at 4.9 per 100,000 in 2017. Overdose deaths involving natural and semi-synthetic opioids (morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone) increased from 3.9 per 100,000 in 2015 to 4.4 in 2016; the rate in 2017 was also 4.4 (Hedegaard et al., 2018; Hedegaard et al. 2017).

Three Waves of Overdose Deaths

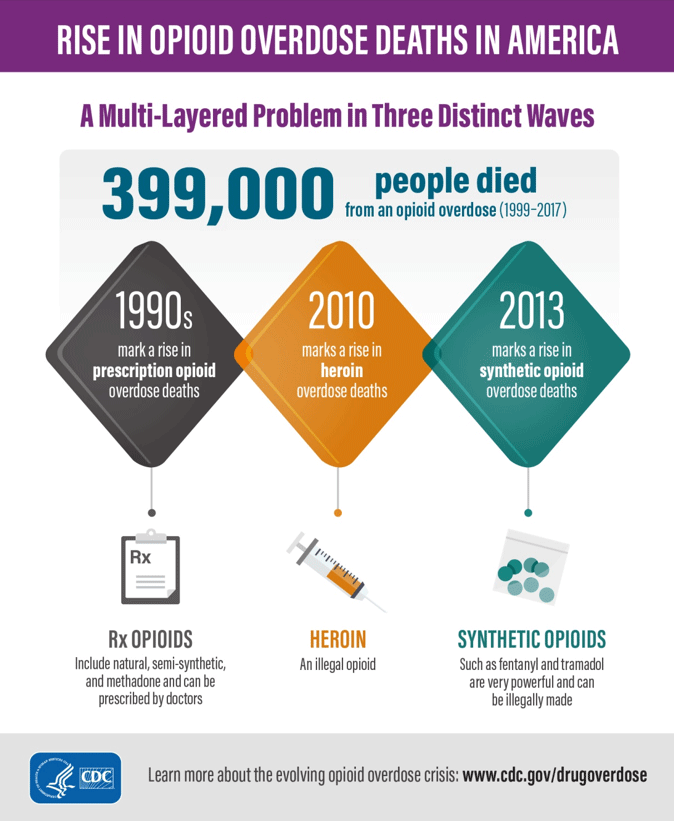

Almost 400,000 people died from an overdose involving an opioid, including prescription and illicit opioids, between 1999 and 2017. The CDC considers the opioid crisis in the United States to have three waves:

- The first wave began with increased prescribing of opioids in the 1990s, with overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (natural and semi-synthetic opioids and methadone).

- The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin.

- The third wave began in 2013, with significant increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids (particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl, which can be found in combination with heroin, counterfeit pills, and cocaine).

Source: CDC, 2019a.

Response in Society

Thousands of consolidated lawsuits have been filed against nearly two dozen big pharma companies, arguing that fault of opioid addiction and overdose deaths lies with virulent advertising campaigns. The campaign against America’s opioid epidemic earned a victory in August 2019 when an Oklahoma judge held Johnson & Johnson responsible for its role in oversupplying addictive drugs. Judge Thad Balkman found that

the company’s ‘false, misleading, and dangerous marketing campaigns have caused exponentially increasing rates of addiction, overdose deaths.’

Balkman also found that Johnson & Johnson was part of a wider collaboration by pharmaceutical makers to change medical policy by “creating the illusion of an epidemic of untreated pain to which opioids were the solution” (McGreal, 2019a).

Patients as Targets

The State of Pennsylvania filed a lawsuit in May 2019 against Purdue Pharma, the company that made billions of dollars with OxyContin. The suit states “Even when Purdue knew people were addicted and dying, Purdue treated patients and their doctors as ‘targets’ to sell more drugs.” Pennsylvania is among the states hardest hit by the opioid epidemic. Roughly 5,390 Pennsylvanians died from drug overdoses in 2017—more than any other state. Most of those deaths were from opioids. The suit continues, “Tragically, each part of Purdue’s campaign of deception earned the company more money, and caused more addiction and death.” Pennsylvania’s Attorney General Josh Shapiro claims that the Purdue supervisors encouraged sales staff to focus on the elderly and veterans, going so far as to establish a website called exitwoundsforveterans.org, which “deceptively assured veterans that Purdue’s opioids are not addictive” (Winter & Schapiro, 2019).

A lawsuit brought by the Washington Post and owners of Gazette-Mail recently resulted in the removal of a protective order to keep from the public the raw data of the Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS) database. Some drug companies and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) fought to keep the information secret, arguing that it contains proprietary details about their business practices and sensitive information used by law enforcement. Now the public can see the astonishing scale of the prescription opioid deluge. The drug industry shipped 76 billion oxycodone and hydrocodone pills over a 7-year period (2006 to 2012) (Achenbach, 2019; Mann, 2019).

5.7 million pills to a town of 300 people

In July 2019, just days after the ARCOS database federal prosecutors charged a former president of a major pharmaceutical distributor (Anthony Rattini, former head of Miami-Luken) with deluging more than 200 pharmacies in West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, and Tennessee with millions of opioid pills and ignoring mounting evidence that they were causing addiction and overdose deaths, and that the drugs were not being dispensed with legitimate prescriptions. Miami-Luken* acknowledged delivering 5.7 million opioid pills to Kermit, West Virginia (population 380 people)—the equivalent of 5,264 pill for every resident including children (McGreal, 2019b).

Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy in September 2019 after reaching a tentative settlement with state and local governments that were suing it over the toll of opioids. The deal, which could be up to $12 billion over time (AP and Strickler, 2019). Purdue Pharma is defending itself in lawsuits from 2,600 governments and other entities.

Bob, a 45-year-old construction worker was being treated in an acute care hospital for a broken femur repair and a low-back, work-related injury. The nurses offered narcotic analgesics around the clock, as ordered, to keep Bob comfortable. (Rather than offer any other comfort measures, it was just easier to administer the narcotic that kept him from using the call light repeatedly.)

After he was discharged, Bob followed up with his primary care physician, who initially prescribed oxycodone and muscle relaxers in a limited supply and without refills, per standard practice. Within one month, Bob returned complaining of constant pain, and he was given a new prescription for oxycodone. The monthly visits became routine and without additional assessments, offering alternative modalities or a narcotic use contract, the prescriptions continued to be written and filled.

Eventually, the medications offered no further pain relief and Bob began supplementing with legal marijuana to provide relief, both of the initial back pain and of the progressive physical craving for the opioid. He visited several other physicians to increase his supply and none of the providers were aware of his multiple visits and duplicated prescriptions.

Bob eventually advanced to street heroin and ultimately overdosed on the combination of opioids that took his life.

What could have been done to avoid this needless loss of life?

What is the role of healthcare professionals in the prescribing and monitoring of opioid drugs?

What is the nurse’s role in the opioid epidemic?

What prevention and treatment strategies are available?

Not every opioid-related death is a stereotypical drug addict who is homeless and helpless. Opioid users include persons of any age, gender, religion, or culture who may have been prescribed opioids for pain control of injuries not their own fault. Often the desire for acute or chronic pain relief evolves to the need for stronger pain control and drug-seeking behaviors driven by the basic desire for pain relief.

Unfortunately, opioid drug users also include those looking for entertainment through narcotic drug use and those who gradually become addicted. For example, compare these two users: one, a teen looking for peer acceptance and entertainment, and the other an educated healthcare professional seeking pain relief; both suffer serious consequences from misuse of the powerful class of drugs known as opioids:

- A 15-year-old female overdosed at a high school party after being given street heroin laced with contaminants.

- A 45-year-old ER physician was caught writing her own prescriptions for oxycodone after suffering from chronic knee pain. Her license was suspended and she was then forced into rehabilitation under the terms of the medical board.

Healthcare professionals who are a part of prescribing or administering opioids need to be aware of the potential for abuse and misuse. Not only do they need to be well informed about the appropriate use and cautions for opioid use but they also need to be able to recognize its effectiveness, side effects, and overdose symptoms, and to recognize abuse in patients as well as their colleagues. Healthcare professionals are actually at greater risk than the general population for opioid abuse because of their access to the drugs.