History of Measles Outbreaks

[Unless otherwise cited, this section was taken from the CDC, 2018a.]

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by the morbillivirus, also known as the rubeola virus. It most commonly affects young children and can easily be prevented by a vaccine, which has been available since 1963. Prior to the modern vaccine, for centuries millions of children contracted measles and many died from its fatal complications.

Measles is an ancient disease and its clinical manifestations were first written about in the seventh century by the Persian doctor Rhazes, who tried to distinguish the measles from smallpox, stating measles was more dreaded than smallpox.

The first written record of measles in the United States was in 1657 by a citizen of Boston, Massachusetts. John Hull, in his personal journal, stated "the disease of measles went through the town, but fortunately there were very few deaths" (College of Physicians, 2020). Twenty years later an English doctor, Thomas Sydenham, published Medical Observations on the History and Cure of Acute Diseases, and successfully distinguished measles from scarlet fever and smallpox. In 1740 German measles was identified by a German physician, Friedrich Hoffmann, as rubella (also called three-day measles).

It wasn't until 1757 that the Scottish physician Francis Home found that the virus was detectable in the blood, and lifelong immunity was possible after recovery from the disease. He produced the disease in healthy people by inoculating people without the disease with blood samples from infected people, proving it was a bloodborne disease.

It is estimated that, prior to the current vaccine, the reported U.S. incidence was at least 12,000 measles-related deaths each year and up to 4 million people were infected annually. Among the reported cases of measles, 8,000 were hospitalized and a thousand suffered encephalitis as a serious and often fatal complication. Up to 75% of measles deaths were of children younger than 5 years old. Prior to the 1950s, nearly all children got the measles and developed active immunity from the active disease (unless they died).

It wasn't until 1954 that a vaccine was created from blood samples of ill students in a breakout in Boston, Massachusetts. Up until then, nearly all children got the measles by age 15. Most children recovered without problem, however it did still cause about 500 deaths annually, which was 0.2% of those with the disease.

Serious complications from measles include:

- Chronic otitis media

- Pneumonia

- Encephalitis

- Corneal ulceration leading to blindness

The measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 after demonstrated safety and efficacy in monkeys and then in humans. In 1968 it was improved and renamed Attenuvax; the new vaccine did not require an additional injection of gamma globulin antibodies to reduce the typical inflammatory reactions. In 1971 Attenuvax was merged in a trivalent combination with the mumps and rubella vaccines to produce the current MMR vaccine in 1971. This combination promotes up to 95% immunity against measles when the first vaccine is received by a child at 12 months of age

In 1971 less than 100 American children had measles due to the widespread availability of the vaccine.

Now, in 2019, cases of measles outpace those of the previous decades. Why is it back after it had been eliminated? Outbreaks in 2013 and 2014 were largely due to unvaccinated children in tight-knit communities of Orthodox Jews in New York, an Amish community in Ohio, a Slavic community in Washington, and a Somali community in Minnesota—all of whom had opted out of the recommended vaccine; this demonstrates the potential for epidemics.

Incidence and Prevalence of Measles

[Material in this section is from CDC, 2019 unless otherwise noted.]

The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1978 set the goal of eliminating measles in the United States population within 3 years, which drastically reduced the incidence of measles by 80%. After an outbreak in 1989, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) then recommended a second dose of MMR vaccine for all children.

Because of the lack of legislation mandating MMR vaccination, low vaccination rates continued to lead to outbreaks. From 1989 to 1991, CDC reported 55,622 cases with 123 deaths, and 90% of cases were unvaccinated children. They stated: "Surveys in areas experiencing outbreaks among preschool-age children indicated that as few as 50% of children had been vaccinated against measles by their second birthday, and that black and Hispanic children were less likely to be age-appropriately vaccinated than were white children (CDC, Pink Book 2018.)

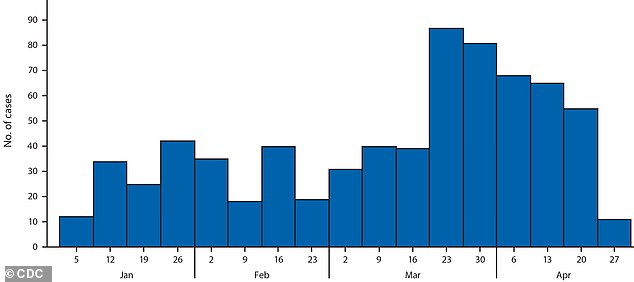

Incidence of Measles Week by Week in the United States,

January through April, 2019

Source: CDC. The year was only a third over, and already there have been more measles cases in 2019 than the United States has seen in 25 years.

The year 2019 is a record year for measles compared with previous decades following the availability of the measles vaccine. The CDC monitors reported cases of measles through the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. This system helps epidemiologists keep track of trends and epidemics to assess for patterns and causes. The 23 states with the highest new cases were New York, New Jersey, Michigan, Washington, and California among unvaccinated communities. An outbreak is defined by three or more cases of measles. Because measles is highly contagious, one case easily becomes more. Compared with another highly contagious disease, 1 Ebola patient likely infects 1.5 persons, while 1 measles patient infects 18 others. Without federal legislation mandating that people be immunized, or adequate federal funding for vaccines, the outbreaks continue.

In the year 2000 the CDC declared it had finally reached the worthy goal of measles eradication in the United States after decades of public health education. The term eliminationhas replaced the term eradication, but it is still limited to the definition of having no reported cases within the past 12 months. Unfortunately, that declaration of measles elimination was reversed in 2010 due the lack of child immunization and the resultant outbreaks throughout the nation.

As of May 2019, 839 cases of measles have been documented in twenty-three states, with 75% of the victims not being immunized and 13% being younger than 12 months of age. Because the first vaccine for measles is not given younger than 12 months of age, these infants become susceptible in outbreaks in close-knit communities. The largest outbreaks have been in New York and Washington. Although national compliance rates for the CDC vaccine recommendations are 95%, 1 in 12 children are still not receiving their first dose of the MMR on time, creating unneeded exposure risk.

Epidemiologic studies have confirmed that the majority of current cases in the United States have been in U.S. citizens who were unvaccinated and then became infected during international travels, bringing measles back to America. Many cases are the children of parents who opt out of the CDC recommendations for measles vaccine. Currently, the government allows people to withhold from vaccine recommendations for religious or personal reasons.

A recent example of the consequences of abstaining from CDC-recommended vaccines is a cruise ship owned by the Church of Scientology that was quarantined in the Caribbean after a crew member was diagnosed with measles. Fearing an outbreak, approximately 300 people onboard were ordered by the health officials of St. Lucia not to embark in St. Lucia but to stay onboard until the danger had past.

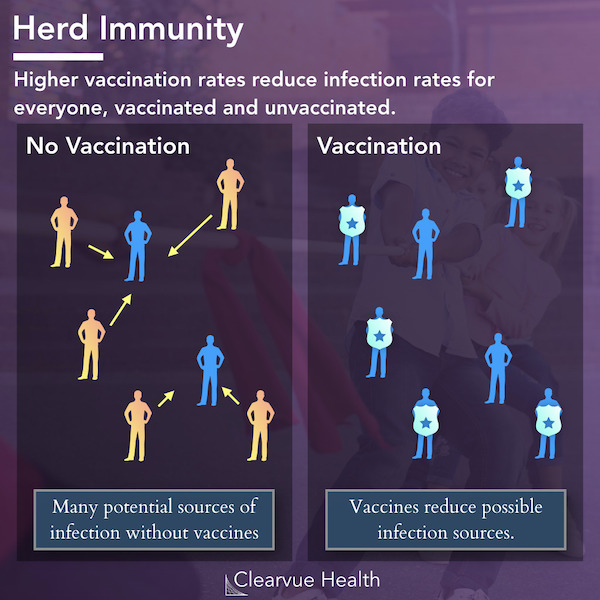

The debate continues between freedom of religious and personal freedom on the one hand and the good of the community on the other. Meantime, herd immunity may be achieved when 95% of a community are immunized; the immunity of the 95% protects the remaining 5%. Notably, when the immunized group decreases, the protection for non-immunized persons decreases also.

Source: CDC.

The Pathophysiology of Measles

The measles virus is transmitted by air as droplets infect the respiratory system; it is manifested in a widespread skin rash. The measles virus is transmitted via the respiratory route and replicates in the nasopharynx and regional lymph nodes within 2 to 3 days after exposure. A secondary viremia occurs 1 week later and is spread to nearby tissues. The incubation period from exposure to prodrome (early stage of symptoms indicating a disease) is 10 to 12 days, with the onset of rash within 14 to 21 days (CDC, 2019). There are 22 known versions of the measles virus.

Six different conditions are caused by the rubeola virus. They include:

- Classic measles.

- Modified measles: someone vaccinated but without adequate immunity. The clinical course is generally not as severe.

- Atypical measles: the clinical syndrome from those who were vaccinated with the killed virus vaccine between 1963 and 1967, who did not receive adequate immunity. They may develop the clinical symptoms, but symptoms may be milder.

- Post-infectious neurologic measles: causes acute decimated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and subacute sclerosing pan encephalitis (SSPE)

- Severe measles.

- Complications: giant cell pneumonia, and measles inclusion-body encephalitis

The Clinical Symptoms

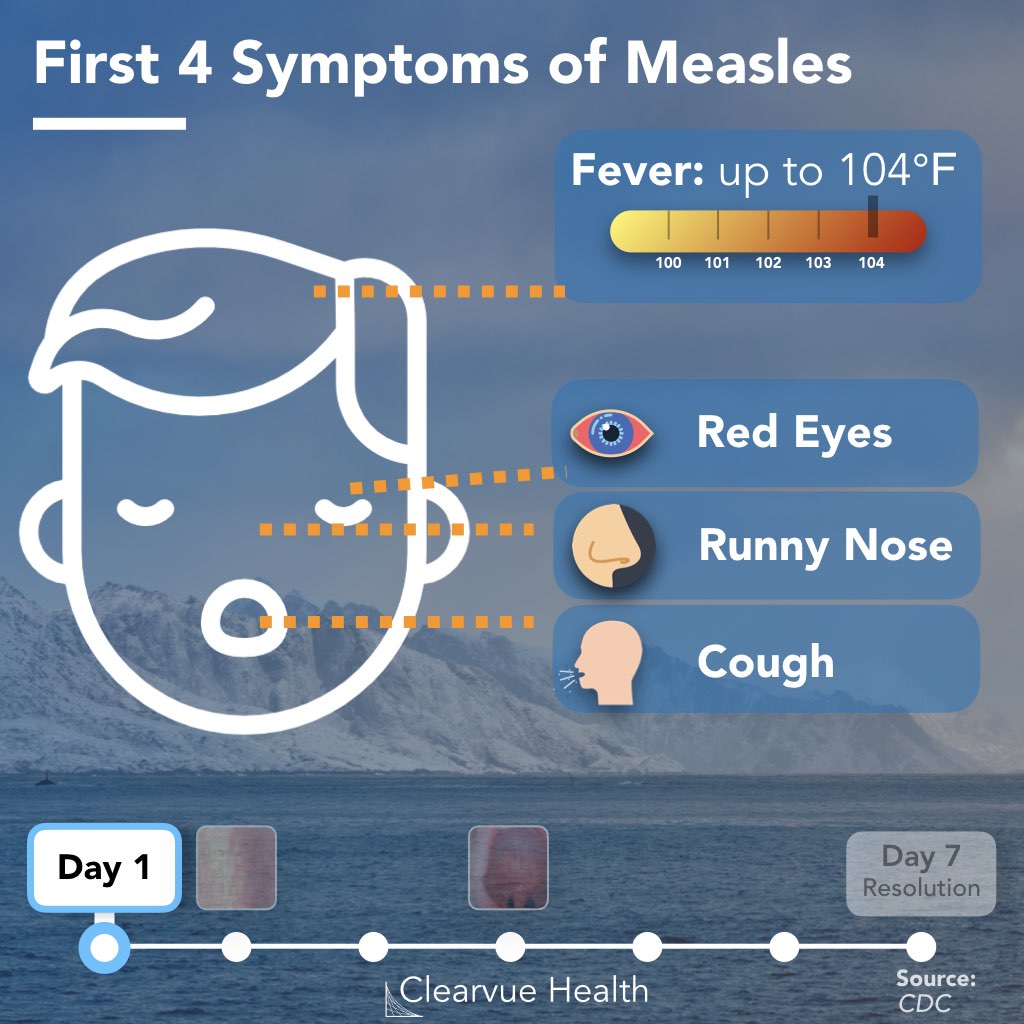

There are four stages of classic measles, which include incubation, prodrome, exanthem stage of rash, and recovery. In the incubation period, patients generally do not feel symptoms for 8 to 10 days and don't know they have been infected.

Source: CDC. Public Domain

The prodrome lasts from 2 to 8 days and includes the symptoms of fever, peaking as high as 105º F, followed by dry hacking cough, runny nose (coryza), and conjunctivitis. The Three "C's" include cough, coryza (rhinitis) and conjunctivitis. Fever is also present and should alert the medical provider to a higher concern than a common cold. Sneezing may also be present, representing the body's response to a respiratory attack.

Red and white spots present on the mucous membrane of the mouth 1 to 2 days before the generalized body rash and are known as Koplik spots—identified by Henry Koplik, an American pediatrician, in 1896 (HxBenefit, 2019). In the palate, the spots look like grains of white sand on a hot red background. Koplik spots, which are specific to measles, generally appear about 48 hours before the rash appears.

Did You Know. . .

Koplik spots are unique to measles and no other medical condition has them. Identifying oral mucosal spots in the posterior of the oral cavity can be helpful in distinguishing measles from other childhood conditions with fever and rash.

The measles exanthem rash is characterized as a maculopapular rash beginning at the head and mouth and progressing downward and outward (confluence) to the chest, hands, and feet, and lasting for less than 1 week. It usually spares the palms and soles of the feet. Initially the lesions blanch but by days 3 to 4 they do not blanch and may create fine desquamation and peeling of hands and feet. The lesions and rash disappear in the same order they appeared. Additional symptoms include anorexia, diarrhea, malaise, and generalized lymphadenopathy as the body works to kill and rid itself of the bloodborne virus. After the rash appears, 48 hours will see additional fevers but recovery of the Koplik. If the rash continues after 48 hours, it is a signal of potential complications.

Measles Rash Seen on Light and Dark Skin

Left: Child with classic measles rash after 4 days. Right: Skin sloughing off of a child healing from measles infection. Source: CDC. Public domain. From https://www.cdc.gov/measles/symptoms/photos.html

Complications are seen in 30% of measles cases, more commonly among children younger than 5 years of age, or adults older than age 20. There have not been many cases of elders with measles because those born before 1963 had childhood exposure and lifetime immunity. Common complications include diarrhea in approximately 8% of cases, otitis media in 7% of cases, and pneumonia in 6% of reported cases; pneumonia is the most common cause of measles-related death, accounting for 60% of those who contract it (CDC, 2019).

Nausea, vomiting, febrile seizures, anorexia, and complications from dehydration may occur. Patients may develop photosensitivity and should protect their eyes if in sunlight during the duration of the illness. Thrombocytopenia also affects the body's ability to clot and may affect bleeding risk. Neuritis and an infection of the optic nerve leading to blindness may result. Encephalitis, toxic encephalopathy, may occur in 1 in 200 people and is a serious complication leading to death.

The person is infectious 4 days after the fever and before the rash appears and continues to be infectious 4days after the rash has appeared. Exposure occurs either by direct contact with the infected person by droplets in the air of the coughing or sneezing measles patient (for up to 2 hours). The virus remains viable even on inanimate objects up to 2 hours. A child who rubs the runny nose and touches others, or objects, may infect others. Approximately 90% of people who are not immunized against measles will develop measles if they inhabit the same household.

Atypical measles is found in persons vaccinated by the inactivated killed measles vaccine (KMV) between 1963 and 1967, which sensitized but didn't protect recipients against the virus. The resultant illness from exposure creates the same clinical symptoms but the rash seems to be limited to the wrist and ankles.

It is recommended that those who received the killed measles vaccine during those years receive the second MMR.

Diagnosing Measles

Not all childhood rashes are measles, but the systemic rash from head to toe is a clinical symptom common to measles. A unique clinical manifestation is the Koplik spots. Although the virus can be isolated from urine, the nasopharynx, blood, and throat cell samples within 7 days of symptoms, it is not routinely done for initial diagnosis. Diagnosis is often done by clinical symptoms, history of international travel, risk factors and exposure to others with measles. Two positive serum specimens are required for positive serologic testing by enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA). Blood tests for measles IgM antibodies is done to confirm reportable cases. A confirmed case must be reported to the local health department, in addition to the infectious disease departments of hospitals and healthcare facilities.

Lab test results may show decreased platelets, low white blood cells, specifically low T-cells, which puts those who are already immunocompromised at greater risk. Chest x-ray may show pneumonitis. In addition to clinical symptoms of Koplik spots and rash, lab values such as circulating antibodies IgM and IgG are helpful in diagnosing the disease. IgM is the most responsive to an acute attack and indicates a recent infection. IgG (think of as "g" for gone) represents the memory of a past infection. The IgM will rise within two days of the rash, is specific for rubeola, and then declines within one month. The IgM capture Elisa and indirect Elisa are diagnostic tests and are both specific and sensitive.

Other diseases that may look similar to measles because of the full-body rashes include rubeola, rubella, erythema infectiosum, roseola infantum, and hand-foot-mouth disease. Many other childhood conditions present with fever and rash and knowing the different clinical presentations can be useful. The following table compares the clinical symptoms of various similar childhood diseases to help identify the differences between them.

Symptoms of Similar Childhood Diseases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Name | Also known as | Age | Pathogen | Signs / | Treatment |

Rubeola | Classic Measles Red Measles | Any age | Rubeola virus | Fever, coryza, cough, conjunctivitis (3 C's), Koplik spots, spreading maculopapular rash from head to feet, anorexia, malaise | Supportive: |

Rubella | 3-day Measles | Any age | Rubeola virus | Same as rubeola without high fever and no Koplik spots. Resolves on own in 72 hours. Joint pain and lymphadenopathy | Supportive for fever and hydration |

Erythema infectiosum | Fifth's disease | 5-14 years | Human Parvovirus B19 | "Slapped cheek" appearance, lacy exanthema on face, arms, legs, trunk and dorsum of feet. Not contagious after fever breaks. Rash may last up to 40 days. | Supportive for fever and hydration |

Roseola Infantum | Sixth Disease | 6 months-2 years | Herpes virus 6 | URI symptoms | Supportive for fever and hydration |

Coxsackie virus | Hand-Foot-and-Mouth disease | Any age | Coxsackie virus | Inflammation of soft palate of mouth and papulovesicular exanthem of hands and feet. Drooling, fever, malaise, poor appetite from painful mouth sores. | Supportive for fever, pain and hydration. |