Well, I found out that race runs deeply throughout all of medical practice. It shapes physicians’ diagnoses, measurements, treatments, prescriptions, even the very definition of diseases. And the more I found out, the more disturbed I became.

Dorothy Roberts

University of Pennsylvania

Social injustices and structural inequities negatively impact the health of many low income and minority communities. This contributes to high disease burdens, difficulties accessing healthcare, and a lack of trust in the healthcare system. These complex and interconnected mechanisms can lead to physiological and psychological stress from repeated daily inequities, which can contribute to chronic diseases (Culhane-Pera et al., 2021).

Power, privilege, and oppression in healthcare are rooted in historic systemic and structural inequalities strongly related to race, gender, class, and economic status. People with more power and privilege have access to better healthcare, while those who are less privileged tend to have limited access to care. Power asymmetries are rooted in a long history of unequal and unfair relationships, including colonialism, imperialism, post-World War II governance structures, and patriarchal norms and practices (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

Power, Privilege, and Oppression

Power: the ability to influence and control material, human, intellectual, and financial resources to achieve a desired outcome. Power is dynamic, played out in social, economic, and political relations between individuals and groups (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

Privilege: a set of typically unearned, exclusive benefits given to people who belong to specific social groups (Global Health 50/50, 2020). Privilege is complex and relational. The social structures that create disadvantages are the same ones that create advantages and benefits (Abimbola et al., 2021).

Oppression: a form of discrimination, leading to disparities. People of color, those with disabilities, and individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to encounter discrimination when seeking healthcare services. This can range from being denied care or receiving lower quality care due to race, gender, or economic status.

Implicit racism is a form of power and oppression that continues to have a profound impact on how patients experience healthcare. Research has shown that Black and Indigenous peoples and other minority groups are more likely to experience poorer health outcomes, be given less-effective treatments, and have a lower quality of care than White Americans.

There is a growing desire to acknowledge and abolish racism and disparities in healthcare institutions. Healthcare advocates have sought to rid clinical care of the pervasive legacy of the biologic determinism of race and have encouraged care providers to understand that race is a sociopolitical construct (Essien and Ufomata, 2021).

These and other strategies can reduce racism and improve cultural competency (Essien and Ufomata, 2021):

- Committing to desegregation of the healthcare system.

- Divesting from racist practice and policy.

- Diversifying the healthcare workforce.

- Ensuring antiracist public health training for health professionals.

- Deepening our investments in the community.

Dismantling oppressive systems requires more than one group of people demanding change. Undoing marginalization requires more than the marginalized speaking up. Many groups—such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color, sex workers, migrants and refugees, women and girls, ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and questioning people—are systematically denied platforms for political, social, and cultural reasons (Abimbola et al., 2021).

2.1 Colonization and Colonial Medicine

Colonization is the process of assuming control of someone else’s territory and applying one’s own systems of law, government, and religion.

Stolen Lives: The Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools / Historical Background

Over the past 500 years, colonization has had a deadly impact on many cultures throughout the world. It has weakened or destroyed cultural practices that helped maintain community health such as traditional food systems, access to clean water, Indigenous languages, and access to land. It replaced long held cultural practices with unsupported and underfunded systems, leading to systemic health disparities, high rates of diabetes, suicide, and cardiovascular diseases (Jensen and Lopez-Carmen, 2022).

While colonial physicians and scientists made substantial contributions to medicine, they worked almost entirely on health issues that were unique to the colonies. The primary focus was controlling and managing the spread of infectious diseases. This was achieved through vaccination campaigns, quarantine measures, and the construction of hospitals and clinics. In doing so, they established a focus on infectious diseases exclusive to the colonies—an interest that has been inherited by global health today (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

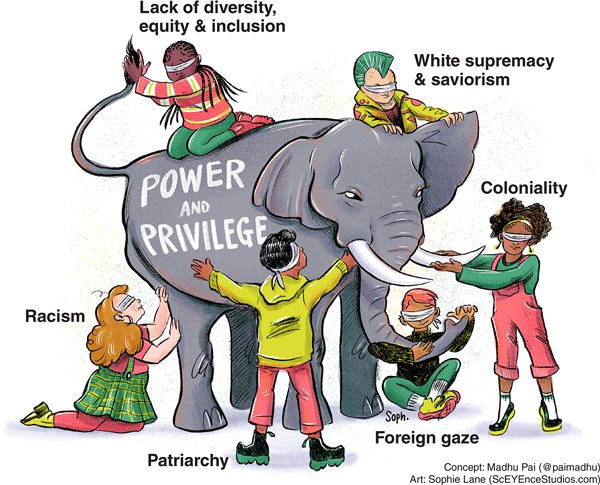

Lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion, White supremacy and saviorism, colonialism, racism, patriarchy, and the “foreign gaze”* have impacted healthcare in the U.S. and throughout the world. Because healthcare education was developed in the shadow of colonialism, it continues to impact diversity and equity.

*Foreign gaze: more than looking at a person—there is an implied imbalance of power or unequal power dynamic; the gazer is superior to and objectifying the object of the gaze. Also: male gaze, imperial gaze, medical gaze.

Global health has many asymmetries in power and privilege. Image source: Madhukar Pai, with artwork by Sophie Lane. Reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

2.2 The Impact of Slavery on Black and Indigenous Peoples

Early travelers to the American West encountered unfree people nearly everywhere they went—on ranches and farmsteads, in mines and private homes, and even on the open market, bartered like any other tradeable good. Unlike on southern plantations, these men, women, and children weren’t primarily African American; most were Native American. Tens of thousands of Indigenous people labored in bondage across the western United States in the mid-19th century.

Kevin Waite

The Atlantic, November 25, 2021

Slavery has cast a long shadow over healthcare for Black and Indigenous Americans. Enslaved people were often denied any form of medical care, while also being subjected to medical experimentation without their consent. Both these practices have had long-lasting effects, resulting in ongoing disparities in access to healthcare, and perpetuating the systemic racism that has plagued the healthcare system for centuries.

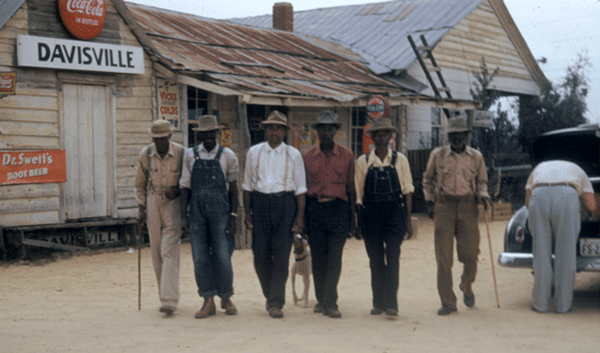

The American medical establishment has a long history of unethical treatment of Black research subjects. Medical ethicist Harriet A. Washington details some of the most egregious examples in her book “Medical Apartheid.” There’s the now notorious Tuskegee syphilis experiment, in which the government misled Black male patients to believe they were receiving treatment for syphilis when, in fact, they were not. That study went on for a total of 40 years, continuing even after a cure for syphilis was developed in the 1940s (Jones, 2021).

Group of men who were test subjects in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments.

Source: Wikimedia. Public domain.

Perhaps less widely known are the unethical and unjustified experiments J. Marion Sims performed on enslaved women in the U.S. in the 1800s that helped earn him the nickname the “father of modern gynecology.” Sims performed experimental vesicovaginal fistula surgery on enslaved women without anesthesia or even the basic standard of care typical for the time (Jones, 2021).

J. Marion Sims experimented on Anarcha, a 17-year-old slave, over 30 times. His decision not to give anesthesia was based on the racist assumption that Black people experience less pain than their White peers—a belief that persists among some medical professionals today (Jones, 2021).

Cases of medical malfeasance and malevolence have persisted, even after the establishment of the Nuremburg code, a set of medical ethical principles developed after World War II and subsequent trials for crimes against humanity (Jones, 2021).

For Indigenous peoples, colonization resulted in the destruction of their existing health practices and the introduction of unfamiliar and inadequate systems, while also resulting in the displacement, exploitation, loss of homelands, and widespread murder of Indigenous peoples. Colonization led to loss of cultural practices, language, traditional medicines, and ways of knowing and being.

When European explorers arrived in the Americas in the late 1400s, they introduced diseases for which the Indigenous peoples had little or no immunity. The impact was rapid and deadly for people living along the coast of New England and in the Great Lakes regions. In the early 1600s, smallpox alone (sometimes intentionally introduced) killed as many as 75% the Huron and Iroquois people.

The exploitation and loss of tribal lands reflects the lasting impact of historical racist policies. Indigenous peoples have been exposed to racist reproductive policies, limited access to reproductive health services, and environmental contamination (Yellow Horse et al., 2020).

Forced onto reservations, Indigenous peoples have been exposed to pollution, pesticides, and lack of clean water. As a group, they are less wealthy, are more often homeless, and experience food insecurity on levels greater than their White counterparts. For example, the Pine Ridge Sioux reservation, home of the Oglala Lakota Nation, has the lowest life expectancy in the U.S, and the second lowest in the entire western hemisphere (Jensen and Lopez-Carmen, 2022).

2.3 Intersectionality

Intersectionality promotes an understanding of human beings as shaped by the interaction of different social locations. These interactions occur within a context of connected systems and structures of power.

Olga Hankivsky

Intersectionality 101

Intersectionality is a social theory that explains how different forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, and classism, intersect and compound to create marginalization and privilege. It highlights the interconnected nature of social identities and the ways in which systems of power interact and overlap to shape individual experiences.

An individual's cultural background is not merely a matter of race or language, but is at the intersection of heritage, language, beliefs, knowledge, behavior, common experience, and self-identity. A culturally sensitive assessment must consider all the aspects that make up cultural diversity, as well as their complex interactions (Mortaz Hejri, Ivan, and Jama, 2022).

By its very nature, health equity is intersectional. This means that individuals belong to more than one group and, therefore have overlapping health and social inequities, as well as overlapping strengths and assets. Understanding how social identities overlap can help a provider better understand, interpret, and communicate health outcomes (CDC, 2022, August 2).

2.4 Gender and Culture

Gender refers to the roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes that a given society at a given time considers appropriate for men and women and people with nonbinary gender identities. These attributes, opportunities and relationships are socially constructed and are learned through socialization. They are context and time-specific and changeable (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

Gender determines what is expected, allowed, and valued in a woman or a man. In most societies there are differences and inequalities between women and men in responsibilities, activities, access to—and control over—power and resources, as well as decision-making opportunities. Gender is part of the broader context of sociocultural power dynamics, as are class, disability status, race, poverty level, ethnic group, sexual orientation, and age (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

Gender equality means having the same opportunities, rights, and potential to be healthy and benefit from the results. Inclusion means actively building a culture of belonging, inviting the contribution and participation of all people, and creating balance in the face of power differences (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

2.4.1 Health Inequities in Perinatal Care

Recognizing the need to humanize birth, the World Health Organization and leading scholars have incorporated “respectful maternity care” as a central tenet of high-quality care. Person-centered maternity care is “care that is respectful of and responsive to women’s preferences, needs, and values and is a core component of quality maternity care” (Ibrahim et al., 2022).

Inequities in the quality of preconception, prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care contribute to racial disparities in maternal health outcomes. Notably, when mode of delivery is disaggregated by race, Black women in the U.S. have the highest rates of cesarean birth, despite similar predisposing factors (Ibrahim et al., 2022).

Black and Indigenous women in the U.S. are significantly more likely to die within a year of giving birth than White women. They also experience disproportionately higher rates of severe maternal morbidity. Nearly half of these maternal events are preventable (Ibrahim et al., 2022).

Improving maternal health and health equity is a key priority. Racism and racial discrimination are linked to poor health, and specifically, negative birth outcomes for women of color and their infants. Mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth has been associated with both short- and long-term adverse mental health outcomes that include pain and suffering, postpartum depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, fear of birth, negative body image, and feelings of dehumanization (Ibrahim et al., 2022).

2.4.2 Reproductive Justice

At United Nations conferences in 1994 (Cairo) and in 1995 (Beijing), participants considered the status of women, population, and development. They adopted the principles of reproductive justice, i.e., that it is a fundamental right to be able to control the number and timing of childbearing. This requires access to family planning information, contraceptive services, and abortion (Speidel and Sullivan, 2023).

Reproductive justice calls for the right to have children or not have children, to choose their number and timing, and the right to live in supportive environments that provide reproductive rights, equal opportunities for women, education, fair wages, housing, and healthcare (Speidel and Sullivan, 2023).

The concept of reproductive justice represents a significant shift from traditional notions of reproductive rights. As described by Ross and colleagues, “The ability of any woman to determine her own reproductive destiny is directly linked to the conditions in her community and these conditions are not just a matter of individual choice and access. For example, a woman cannot make an individual decision about her body if she is part of a community whose human rights as a group are violated, such as through environmental dangers or insufficient quality healthcare” (Fleming et al, 2019).

The recent Supreme Court ruling overturning Roe v. Wade has already affected pregnancy-related healthcare for many women. It has also impacted OB/GYN training in the states that have restricted abortion services. This means some hospitals will no longer offer vital training used to manage miscarriages and other pregnancy-related complications.