Power, privilege, and oppression in healthcare are rooted in historic systemic and structural inequalities strongly related to race, gender, class, and economic status. People with more power and privilege have access to better healthcare, while those who are less privileged tend to have limited access to care. Power asymmetries are rooted in a long history of unequal and unfair relationships, including colonialism, imperialism, post-World War II governance structures, and patriarchal norms and practices (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

These social and structural inequities impact the health of many low income and minority communities, contributing to high disease burdens, difficulties accessing healthcare, and a lack of trust in the healthcare system. These complex and interconnected issues can contribute to chronic disease due to physiological and psychological stress from repeated daily inequities (Culhane-Pera et al., 2021).

Definitions: Power, Privilege, and Oppression

Power: the ability to influence and control material, human, intellectual, and financial resources to achieve a desired outcome. Power is dynamic, played out in social, economic, and political relations between individuals and groups (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

Privilege: a set of typically unearned, exclusive benefits given to people who belong to specific social groups (Global Health 50/50, 2020). Privilege is complex and relational. The social structures that create disadvantages are the same ones that create advantages and benefits (Abimbola et al., 2021).

Oppression: a form of discrimination, leading to disparities. People of color, those with disabilities, and individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to encounter discrimination when seeking healthcare services. This can range from being denied care or receiving lower quality care due to race, gender, or economic status.

Dismantling oppressive systems requires more than one group of people demanding change. Undoing marginalization requires more than the marginalized speaking up. Many groups—such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color, sex workers, migrants and refugees, women and girls, ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and questioning people—are systematically denied platforms for political, social, and cultural reasons (Abimbola et al., 2021).

3.1 Colonization and Colonial Medicine

Colonization is the process of assuming control of someone else’s territory and applying one’s own systems of law, government, and religion.

Stolen Lives: The Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools / Historical Background

Colonization has had—and continues to have—a deadly impact on many cultures throughout the world. It has weakened or destroyed cultural practices that helped maintain community health such as traditional food systems, access to clean water, Indigenous languages, and access to land. It replaced long held cultural practices with unsupported and underfunded systems, leading to systemic health disparities, high rates of diabetes, suicide, and cardiovascular diseases (Jensen and Lopez-Carmen, 2022).

While colonial physicians and scientists made substantial contributions to medicine, they worked almost entirely on health issues that were unique to the colonies. The primary focus was controlling and managing the spread of infectious diseases. This was achieved through vaccination campaigns, quarantine measures, and the construction of hospitals and clinics. In doing so, they established a focus on infectious diseases exclusive to the colonies—an interest that has been inherited by global health today (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

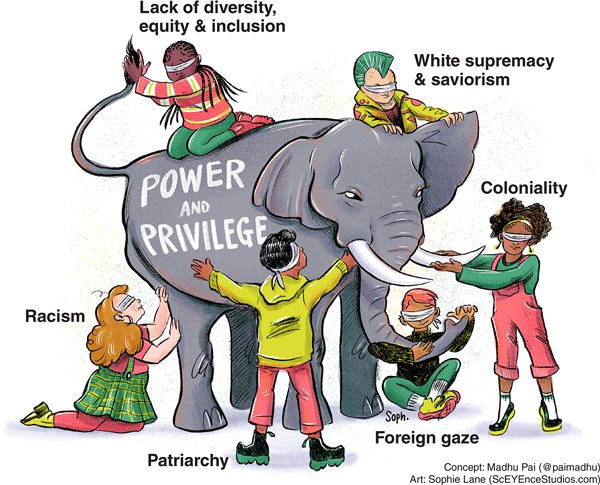

Lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion, white supremacy and saviorism, colonialism, racism, patriarchy, and the “foreign gaze” * have impacted healthcare in the U.S. and throughout the world. Because healthcare education was developed in the shadow of colonialism, it continues to impact diversity and equity.

*Foreign gaze: more than looking at a person—there is an implied imbalance of power or unequal power dynamic; the gazer is superior to and objectifying the object of the gaze. Also: male gaze, imperial gaze, medical gaze.

Global health has many asymmetries in power and privilege. Image source: Madhukar Pai, with artwork by Sophie Lane. Reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

3.2 Intersectionality

Intersectionality promotes an understanding of human beings as shaped by the interaction of different social locations. These interactions occur within a context of connected systems and structures of power.

Olga Hankivsky

Intersectionality 101

An individual’s cultural background is not merely a matter of race or language, but is at the intersection of heritage, language, beliefs, knowledge, behavior, common experience, and self-identity. A culturally sensitive assessment must consider all the aspects that make up cultural diversity, as well as their complex interactions (Mortaz Hejri, Ivan, and Jama, 2022).

Intersectionality is a social theory that explains how different forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, and classism, intersect and compound to create marginalization and privilege. It highlights the interconnected nature of social identities and the ways in which systems of power interact and overlap to shape individual experiences.

By its very nature, health equity is intersectional. This means that individuals belong to more than one group and, therefore have overlapping health and social inequities, as well as overlapping strengths and assets. Understanding how social identities overlap can help a provider better understand, interpret, and communicate health outcomes (CDC, 2022, August 11).