The ugly reality is that dementia often manifests as a relentless and cruel assault on personhood, comfort, and dignity. It siphons away control over thoughts and actions, control that we take for granted every waking second of every day.

Michael J. Passmore

Geriatric Psychiatrist, University of British Columbia

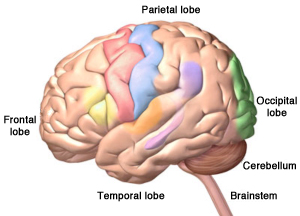

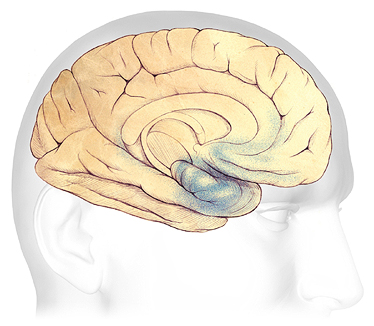

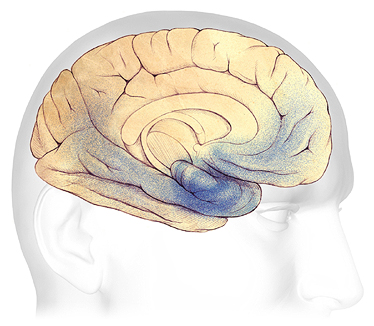

An illustration of the cerebrum, cerebellum, and the brainstem. The outer surface of the cerebrum is made up of a thin layer of nerve cells called the cerebral cortex. Source: Zygote Media. Used with Permission.

Brain disease comes in many different forms and has many different causes. Because the brain is so important, any damage to the brain can have a profound impact on our ability to manage daily affairs, communicate effectively, and live independently. Dementia is a syndrome, a collection or grouping of symptoms—the result of progressive deterioration and loss of brain cells and brain mass.

The largest part of the human brain, the cerebrum, has four lobes: the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. The most recognizable and devastating effects of dementia occur because of damage to nerve cells on the outer surface of the lobes—the cerebral cortex.

Common Brain Diseases

Different types of dementia affect different parts of the brain. Some start in a part of the brain that controls a specific function such as memory or emotions. Other dementias affect the entire brain—or more than one part of the brain—causing other symptoms.

Although a small percentage of people experience early-onset dementia, in general, dementia develops in later adulthood. Aging is a risk factor for developing dementia but nevertheless dementia is not considered a normal part of aging.

In addition to Alzheimer’s disease there are several other types of dementia:

- Vascular dementia

- Frontotemporal dementia

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease

- Post-stroke dementia

In all, nearly twenty different types of non-Alzheimer’s dementia have been identified. Determining if someone has dementia is important because some types of cognitive decline are treatable and reversible if the underlying cause is identified and treated (Sönke, 2013).

Did You Know . . .

For some time now, we have used the term “Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias” to describe dementia and to make it clear that there is more than one kind of dementia. The term neurocognitive disorder is now recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as a new term for dementia.

Alzheimer’s Dementia

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an irreversible, progressive, age-related brain disorder that affects as many as 5 million Americans age 65 and older. Along with heart disease and cancer, it is a leading cause of death for older people (ADEAR, 2014). Memory problems are a common early symptom of Alzheimer’s dementia although language difficulties, apathy, depression, and vision and spatial difficulties can also be early symptoms. Although more than twenty types of dementia have been identified, Alzheimer’s dementia is the most frequent (and most studied) cause of dementia in older adults.

Did You Know . . .

Worldwide more than 35 million people live with dementia and this number is expected to double by 2030 and triple by 2050.

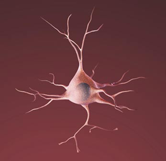

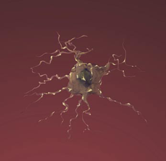

The exact cause of Alzheimer’s dementia is still unknown. Brain imaging techniques such as MRIs as well as autopsies show that Alzheimer’s causes the brain to shrink, that connections between nerves weaken and nerve cells are damaged and lost. Once a healthy nerve cell begins to deteriorate, it loses its ability to communicate with other neurons, with devastating results.

Degeneration of Cerebral Neurons

Left: A healthy nerve cell with many connections to other cells. Right: A dying nerve cell showing the nerve connections weakening and the main body of the cell deteriorating. Source: ADEAR, 2014.

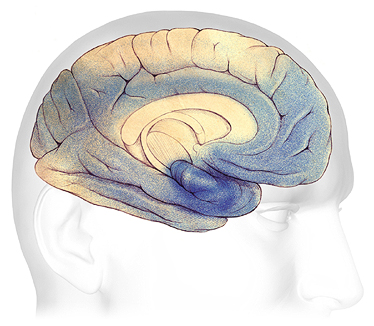

In Alzheimer’s, damage is thought to be associated with the formation of unwanted structures called beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (plaques and tangles). The progressive brain damage associated with Alzheimer’s dementia is illustrated in the drawings below, which show the formation and spread of plaques and tangles (in blue). The blue areas represent damaged and dying nerve cells.

In Alzheimer’s disease, plaques and tangles first appear in an area of the temporal lobe called the hippocampus, where new memories are formed (A). As the disease progresses, plaques and tangles spread to the front part of the brain, affecting judgment and other high-level cognitive functions; symptoms begin to be obvious at this stage (B). In the severe stage (C), plaques and tangles are found throughout the brain. Damage eventually affects memory, emotions, communication, safety awareness, logical thinking, recognition of loved ones, and the ability to care for oneself.

The Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease

A

B

C

A: Plaques and tangles (shaded in blue) are beginning to form within the hippocampus. B: As the disease progresses, they spread towards the front and rear of the brain. C: In severe Alzheimer’s, plaques and tangles cause widespread damage throughout the brain. Source: The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

Vascular Dementia and Vascular Cognitive Impairment

Vascular dementia is one of the most common forms of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease, affecting approximately 20% of the dementia cases worldwide (Neto et al., 2015). Risk factors for developing vascular dementia include diseases or disorders that damage the vessels supplying blood to the brain (heart rhythm irregularities, high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, smoking, small strokes, and obesity). The risk of developing dementia from vascular damage can be significant even when individuals have suffered only small strokes or minor damage to the blood vessels (NINDS, 2013).

Frontotemporal Dementia

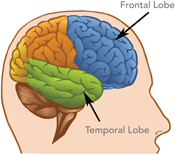

Damage to the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes causes forms of dementia called frontotemporal disorders. Source: National Institute on Aging.

Frontotemporal dementia begins in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Although new research is showing that frontotemporal dementia can start in older age, the belief has been that it starts at an earlier age than Alzheimer’s disease and is a relatively common type of dementia in those under the age of 60.

Because frontotemporal dementia can also affect the hippocampus and because of the many variations found in the disease, it is often difficult to tell the difference between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. It can also be confused with other psychiatric conditions such as late-onset schizophrenia.

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is another common type of progressive dementia. It accounts for up to 20% of all autopsy-confirmed dementias in elders (Vermeiren et al., 2015).

DLB is caused by the build-up of abnormal proteins called Lewy bodies inside nerve cells in areas of the brain responsible for certain aspects of memory and motor control. It is not known exactly why Lewy bodies form or how Lewy bodies cause the symptoms of dementia (NINDS, 2017).

The similarity of symptoms between dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease can make diagnosis difficult. It is possible that either Lewy body dementia is related to these other causes of dementia or that an individual can have more than one type of dementia at the same time. Lewy body dementia usually occurs in people with no known family history of the disease. However, rare familial cases have occasionally been reported (NINDS, 2017).

Parkinson’s Disease Dementia

Mild cognitive impairment is common in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease and a majority of people with Parkinson’s disease will eventually develop dementia. The time from the onset of movement symptoms to the onset of dementia symptoms varies greatly from person to person.

Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s dementia are now recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, where they are respectively coded as “Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorder with Lewy Bodies” and as “Major and Mild Neurocognitive Disorder due to Parkinson’s Disease” (Donaghy and McKeith, 2014).

Post-Stroke Dementia

As many as two-thirds of stroke patients experience cognitive impairment or cognitive decline following a stroke; approximately one-third go on to develop dementia. The risk for cognitive impairment or decline is increased by a history of stroke. The risk for developing dementia may be 10 times greater among individuals with stroke than those without. Mortality rates among stroke patients with dementia are 2 to 6 times greater than among stroke patients without dementia (Teasell et al., 2014).

Functional Impairments

Dementia impairs judgment, alters visual-spatial perception, and decreases the ability to recognize and avoid hazards (Eshkoor et al., 2014). It also affects short-term memory and is thought to impair working memory, a type of memory that promotes active short-term maintenance of information for later access and use. The decline in working memory also affects language comprehension and visuospatial reasoning (Kirova et al., 2015).

When cognitive impairment is mild, studies indicate that lower attention/executive function or memory function may lead to a decline in gait speed. Slow gait speed may indicate deficits in the cognitive-processing speed or in executive and memory functions. The decline in cognitive function in people with mild cognitive impairment is not uniform, but rather depends on the type of cognitive impairment (Doi et al., 2014).

Because of these visual and perceptual changes, walking on a busy street can be dangerous, driving is no longer safe, and navigating around obstacles such as curbs, breaks in the sidewalk, stairs, and pets is a challenge. Visual and spatial difficulties also affect reading, comprehension of form and color, peripheral vision, and the ability to see contrast. This can make it difficult to accurately detect motion and process visual information (Quental et al., 2013).

Teepa Snow: Aging Vision and Alzheimer’s (2:49)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqbxFD2-lsQ

Vascular dementia can cause impaired decision-making and judgment; mood changes are also common. Symptoms often begin suddenly and progress in a “step-wise” manner. This means the symptoms stay the same for a period of time, and then suddenly get worse, usually as a result of additional small strokes or other vascular damage. Mental impairment often seems “patchy,” because of the many different areas of the brain that are affected.

In the early stages of frontotemporal dementia, judgment and decision making are more affected than memory. There is a progressive change in behavior (mood changes, apathy, and disinhibition*), difficulties with language, and weakness or slowing of movement. People with frontotemporal dementia gradually lose control of their impulses—their behavior is often referred to as “odd,” “socially inappropriate,”, and “schizoid.”

*Disinhibition: a loss of inhibition, a lack of restraint, disregard for social convention, impulsiveness, poor safety awareness, an inability to stop strong responses, desires, or emotions.

The impulsive behavior and lack of judgment seen in people with frontotemporal dementia can cause inappropriate behaviors such as stealing, falling prey to internet or phone scams, excessive shopping, indecent exposure, and obsessive-compulsive behaviors such as pacing and hoarding.

Functional impairments associated with dementia with Lewy bodies include progressive cognitive decline, “fluctuations” in alertness and attention, visual hallucinations, and parkinsonian motor symptoms, such as slowness of movement, difficulty walking, or rigidity (stiffness) (NINDS, 2017). Nearly half of those with DLB also suffer from depression (Vermeiren et al., 2015). Difficulty sleeping, loss of smell, and visual hallucinations can precede movement and other problems by as long as 10 years. Because of this, DLB can go unrecognized or be misdiagnosed as a psychiatric disorder until its later stages (NINDS, 2013).

Functional impairments associated with Parkinson’s disease dementia include the onset of Parkinson-related movement symptoms followed by mild cognitive impairment and sleep disorders, which involves frequent vivid nightmares and visual hallucinations (NINDS, 2013). Cognitive issues such as impaired memory, lack of social judgment, language difficulties, and deficits in reasoning can develop over time. Autopsy studies show that people with Parkinson’s dementia often have amyloid plaques and tau tangles similar to those found in people with Alzheimer’s disease, though it is not understood what these similarities mean.