In the United States in the previous year about 25 million adults reported pain every day for the previous three months and nearly 40 million adults reported severe pain. Individuals with severe pain have worse health, use more healthcare, and have more disability than those with less severe pain (NCCIH, 2020).

Prescription opioid medications can help treat and manage severe pain but may pose risks for addiction, overdose, and death. These risks are increased when patients are prescribed higher doses of prescription opioids.

Misuse of prescription opioids is a risk factor for heroin use; 80% of people initiating heroin use report prior misuse of prescription opioids (NIDA, 2017). Improving the way opioids are prescribed can ensure patients have access to safer, more effective chronic pain treatment while reducing the number of people who misuse or overdose from these drugs.

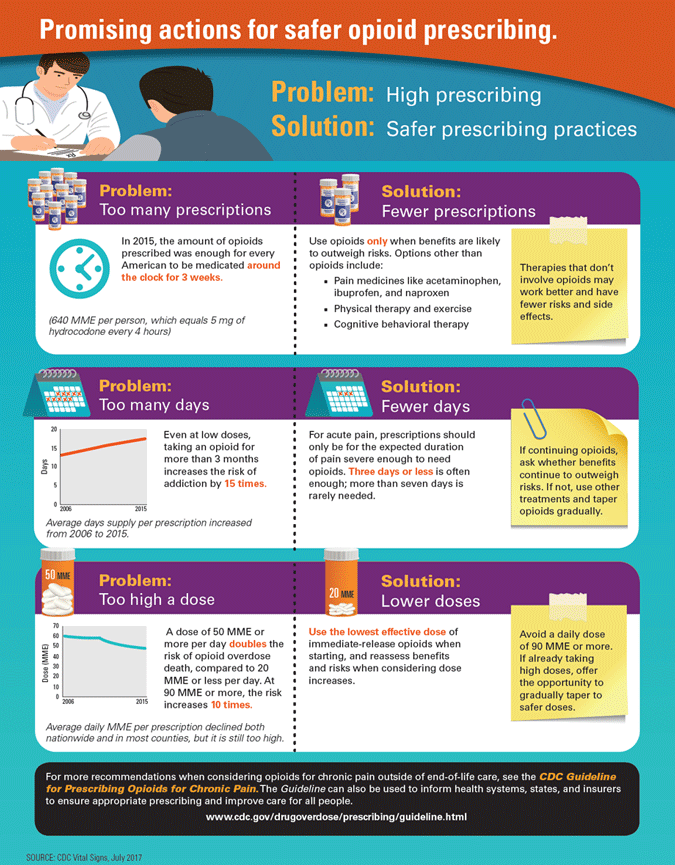

CDC has identified three problem areas:

- Too many prescriptions

- Too many days

- Too high a dose (CDC, 2017, July 6)

Source: CDC, 2017, July 6.

New Jersey Prescribing Regulations

When prescribing controlled dangerous substances, including opioids in any schedule, providers must:

- Take a thorough history, including any history of substance use disorder;

Then, either- Conduct a physical exam in-person; or

- During the current COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), conduct an exam by telemedicine. For prescribing at a first visit, this telemedicine exam must be conducted using real time, interactive, audio-visual methods.

- For subsequent visits, a phone encounter is permitted.

- Develop a treatment plan with identified goals. (New Jersey Consumer Affairs, 2020)

The following requirements also apply, unless the prescription is being issued to a patient being treated for cancer, receiving hospice care, or residing in long term care facility, or the prescription is for treatment of substance use disorder, or if medications are being administered pursuant to medication orders in in-patient facilities:

When issuing an initial prescription for a Schedule II CDS or any opioid for patients suffering from acute pain, the prescriber must:

- Discuss the risks and benefits of opioid treatment and alternatives;

- Limit the prescription to no more than a 5-day supply at the lowest effective dose of an immediate-release formulation;

If, after the initial 5-day prescription, the patient requests a subsequent opioid prescription, the prescriber must:

- Wait until at least the 4th day from the date of the initial prescription;

- Determine, after a consultation, in-person or by telephone, that an additional supply is necessary and does not present a risk of abuse, addiction or diversion;

- Tailor the supply to the patient’s need, and never provide more than 30 days.

When prescribing opioids to a patient for chronic pain (pain beyond 3 months), every 3 months the prescriber must:

- Reiterate the discussion of the risks of opioids;

- Enter into a pain management agreement with the patient;

- Reassess treatment goals and make a reasonable periodic effort to taper or stop the prescribing;

- During the current COVID-19 PHE, prescribers must also co-prescribe naloxone if the patient has one or more prescriptions totaling 90 MME or more each day, or is concurrently obtaining an opioid and a benzodiazepine. (New Jersey Consumer Affairs, 2020)

For patients with chronic pain, opioids are associated with small beneficial effects versus placebo but are associated with increased risk of short-term harms and do not appear to be superior to nonopioid therapy. Evidence on intermediate-term and long-term benefits remains limited, and additional evidence confirms an association between opioids and increased risk of serious harms that appears to be dose-dependent. Research is needed to develop accurate risk prediction instruments, determine effective risk mitigation strategies, clarify risks associated with co-prescribed medications, and identify optimal opioid tapering strategies (AHRQ, 2019).

The Dilemma in Acute Pain Management

Acute pain occurs in response to noxious stimuli and is normally sudden in onset and time limited. It usually lasts for less than 7 days but can extend up to 30 days; for some conditions, acute pain episodes may recur periodically. In some patients, acute pain persists to become chronic.

The dilemma in the medical management of acute pain is selecting an intervention that provides adequate pain relief, improves function, and facilitates recovery, while minimizing adverse effects and avoiding overprescribing of opioids. When acute pain is adequately treated, it may prevent the transition to chronic pain (AHRQ, 2020, January 2).

Many factors influence acute pain management. For example, post operative pain is usually managed with multimodal strategies in a monitored setting prior to discharge. By contrast, treatment of pain in an outpatient setting can be more difficult. A treatment that is effective for one acute pain condition and patient in a particular setting may not be effective in others (AHRQ, 2020, January 2).

Guideline for Chronic Pain

In response to the opioid crisis, in 2016, CDC developed the Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. The guideline included a recommendation to limit opioids for acute pain in most cases to 3 to 7 days. This recommendation was based on evidence showing an association between use of opioids for acute pain and long-term use. In the last several years, over 25 states have passed laws restricting prescribing of opioids for acute pain (AHRQ, 2020, January 2).

The guideline provides recommendations for primary care clinicians who are prescribing opioids for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care. It addresses (1) when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain; (2) opioid selection, dosage, duration, followup, and discontinuation; and (3) assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use (Dowell et al., 2016).

Key points:

- Long-term opioid use often begins with the treatment of acute pain.

- Prescribe the lowest effective dose possible.

- Non-opioid therapies are preferred for chronic pain.

- Establish treatment goals and reassess throughout treatment.

- Prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting opioids.

- Evaluate benefits and harms within 1 to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy.

- Evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms.

- Use a validated screening tool. (NIDA, 2017)

In addition:

- Use Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) to determine concurrent opioid use.

- Use urine drug test screening to test for concurrent illicit drug use.

- Avoid concurrent prescribing of other opioids and benzodiazepines if possible.

- Offer evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorders. (NIDA, 2017)

On January 1, 2018, the Joint Commission implemented revised pain assessment and management standards. The new standards, state that hospitals must:

- Establish a clinical leadership team.

- Engage medical staff and hospital leadership in improving pain assessment and management.

- Provide at least one non-pharmacologic pain treatment modality.

- Facilitate access to Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs.

- Concentrating on how pain is affecting patients’ physical function.

- Engage patients in treatment decisions.

- Address patient education and engagement.

- Referral patients addicted to opioids to treatment programs. (Joint Commission, 2020)

Breaking the Stigma

The primary problem with the opioid epidemic is simple: It is easier to get high than it is to get help. People who need substance use treatment sometimes do not have access to treatment. Stigma surrounding substance use disorders remains high. To avoid stigmatizing a person, consider the following strategies:

- Avoid labels (“addict,” “junkie,” or “drug user”).

- Use “person first” language.

- Understand that drug use falls along a continuum.

- Be aware of unintentional bias.

- Reflect on your own experiences.

- Understand that substance misuse is often linked to trauma.