If you find race-specific medicine surprising, wait until you learn that many doctors in the United States still use an updated version of a diagnostic tool that was developed by a physician during the slavery era, a diagnostic tool that is tightly linked to justifications for slavery.

Dorothy Roberts

University of Pennsylvania

Historical racism and structural inequalities have contributed to a longstanding mistrust of the medical system among marginalized communities. Historical power imbalances have had profound consequences on certain racial and ethnic groups: early deaths, unnecessary disabilities, and enduring injustices and inequalities (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

Structural racism promotes public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms that perpetuate racial and ethnic inequity. It is rooted in a hierarchy that privileges one race over another, influencing institutions that govern daily life, from housing policies to police profiling to incarceration (Muramatsu and Chin, 2022).

Over centuries, structural racism has become entrenched, influencing the way medicine is taught and practiced as well as the functioning of healthcare organizations (Geneviève et al., 2020). The unequal burden of COVID-19 on underserved populations has forced the medical community to reckon with uncomfortable truths about its role in perpetuating structural racism in modern society. A race-conscious conversation in medicine is evolving that acknowledges race as a social construct that creates and upholds barriers underlying health disparities (Santos, Dee, and Deville, 2021).

Online Resource

Video: Dorothy Roberts: The problem with race-based medicine [14:27]

Source: TEDMED, 2015.

Diagnostic tools developed over time can reflect the impact of structural racism. During the COVID pandemic, pulse oximetry was used extensively, and critical treatment decisions were made partly based upon a person’s oxygen saturation. For some patients, life-saving therapies were delayed because pulse oximeters over-estimated oxygen saturation levels in darker-skinned individuals. There is evidence that, for Black and Hispanic patients, undetected low oxygen levels led to delays in receiving therapies such as remdesivir and dexamethasone, and in many cases, led to no treatment at all (Fawzy et al., 2022).

Although pulse oximetry is a fundamental tool used in diagnosis and management decisions, the device’s lack of accuracy in certain populations has not been adequately investigated. This is even though the issue has been recognized for several decades and was highlighted in a 2020 safety communication by the Food and Drug Administration (Fawzy et al., 2022).

Adding to the problems, pulse oximeters have migrated out of the acute care setting and are now available and affordable to the average consumer for home use. The expanded use of a differentially inaccurate device potentially exacerbates racial and ethnic health disparities (Fawzy et al., 2022).

The Impact of Colonial Medicine

Colonial medicine refers to the medical practices and treatments that were used during the period of colonization by European powers in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. It was based on traditional European medical practices and was heavily influenced by the beliefs and practices of the colonizing power.

Colonial medicine focused on 3 areas: (1) protecting European health, (2) maintaining military superiority, and (3) supporting extractive industries*. Colonial medicine emphasized malaria, yellow fever, sleeping sickness, and other specific diseases, focusing on bacteriological approaches to disease control (Global Health 50/50, 2020). This was achieved through vaccination campaigns, quarantine measures, and the construction of hospitals and clinics.

*Extractive industries: Companies and activities involved in the removal of resources for processing and sale such as oil, sand, rock, gravel, metals, minerals, and other material.

While colonial physicians and scientists made substantial contributions to medicine, they worked almost entirely on health issues that were unique to the colonies. In doing so, they established a focus on infectious diseases exclusive to the colonies (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

In the post-colonial periods, European and American special interest groups have used their leverage to shape a continuing focus on diseases through, for example, public-private partnerships for drug development. Virtually all major pharmaceutical manufacturers either produced or have evolved from firms that supplied medicines to sustain colonialism (Global Health 50/50, 2020).

Medical knowledge and practices brought by European colonizers had an impact on traditional medical practices of Indigenous communities living in the Americas that continues to this day. Indigenous peoples were forced to abandon traditional medical practices and adopt Western treatments, which were sometimes ineffective or even harmful. Colonial policies led to the displacement, forced relocation, and murder of Indigenous populations, the effects of which continue to impact the health and well-being of Indigenous communities today.

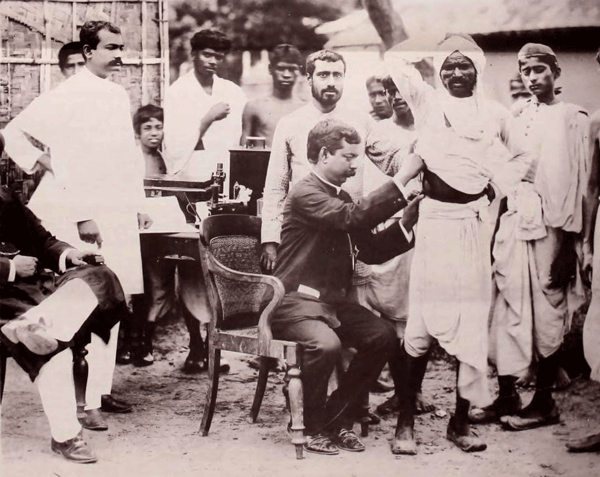

Anti-cholera vaccination, Calcutta, 1895. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

The Impact of Slavery

The systemic discrimination that has impacted Black health dates back to the first ships carrying enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. The colonial narrative of hierarchy and supremacy exists to this day, and has translated, centuries later, into gaping health disparities.

Meghana Keshavan, STAT Health, June 9, 2020

It has been many years since the abolition of slavery, yet its legacy remains. Social injustices related to historical trauma and structural racism continue to negatively impact the health of many low income and minority communities. These mechanisms contribute to high disease burdens, difficulties accessing healthcare, and a lack of trust in the healthcare system (Culhane-Pera et al., 2021).

There has been a long history of unethical treatment of Black research subjects in medical research, exacerbating this lack of trust. Cases of medical malfeasance and malevolence persisted, even after the establishment of the Nuremburg code* (Jones, 2021).

*Nuremburg code: A set of medical-ethical principles for human experimentation developed after World War II. It established the absolute requirement for voluntary consent for medical experiments involving human beings.

Medical ethicist Harriet A. Washington details some of the most egregious examples of unethical treatment of Black subjects in her book “Medical Apartheid.” In the notorious Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, the government misled Black male patients to believe they were receiving treatment for syphilis when, in fact, they were not. That study went on for a total of 40 years, continuing even after a cure for syphilis was developed in the 1940s (Jones, 2021).

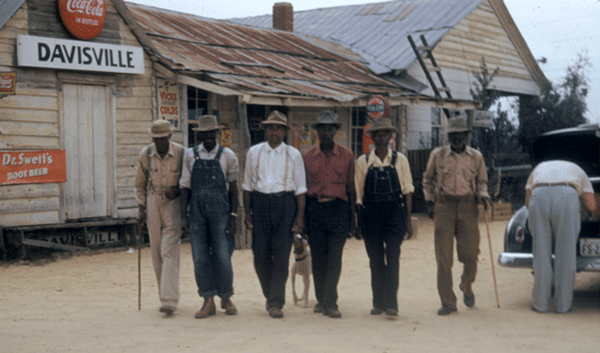

Group of men who were test subjects in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments. Source: Wikimedia. Public domain.

Perhaps less widely known are the experiments J. Marion Sims performed on enslaved women in the United States in the 1800s. The experiments earned Sims the nickname the “father of modern gynecology.” Sims performed experimental surgery on enslaved women without anesthesia or even the basic standard of care typical for the time. Historian Deirdre Cooper Owens elaborates on this case and many other ways Black women’s bodies have been used as guinea pigs in her book “Medical Bondage” (Jones, 2021).

J. Marion Sims experimented on Anarcha, a 17-year-old slave, over 30 times. His decision not to give anesthesia was based on the racist assumption that Black people experience less pain than their white peers—a belief that persists among some medical professionals today (Jones, 2021).

Impact of Colonization and Slavery on Native Americans

Early travelers to the American West encountered unfree people nearly everywhere they went—on ranches and farmsteads, in mines and private homes, and even on the open market, bartered like any other tradeable good. Unlike on southern plantations, these men, women, and children weren’t primarily African American; most were Native American. Tens of thousands of Indigenous people labored in bondage across the western United States in the mid-19th century.

Kevin Waite

The Atlantic, November 25, 2021

The impact of colonization on the health of Indigenous peoples has been atrocious. When European explorers arrived in the Americas in the late 1400s, they introduced diseases for which the native people had little or no immunity. The impact was rapid and deadly for people living along the coast of New England and in the Great Lakes regions. In the early 1600s, smallpox alone (sometimes intentionally introduced) killed as many as 75% the Huron and Iroquois people.

In North America, colonizers did not consider Indigenous people to be “people” at all. They did not consider their laws, governments, medicines, cultures, beliefs, or relationships to be legitimate. The colonizers believed that they had the right and moral obligation to make decisions affecting everybody, without consultation with Indigenous people. These beliefs and prejudices were used to justify the acts and laws that came into being as part of the process of colonization (Wilson, 2018).

Colonization led to loss of cultural practices, language, traditional medicines, and ways of knowing and being. With forced assimilation, health inequities grew while traditional healing practices were forcibly replaced (Coen-Sanchez et al., 2022). Indigenous people have been exposed to racist reproductive policies, limited access to reproductive health services, and environmental contamination (Yellow Horse et al., 2020).

The Health Impact of Extractive Industries on Native Americans

Extractive industries have had a lasting impact on the health and well-being of Indigenous communities worldwide. Even during normal operations of mining and energy projects, community health is often a concern (Bernauer and Slowey, 2020).

Historically, uranium extraction has significantly affected some Indigenous communities. There is substantial evidence that living near an abandoned uranium mine is associated with reproductive damage. Abandoned uranium mines are not only associated with environmental contamination, but also closely related to structural inequalities such as a higher percentage of households without complete plumbing and access to safe water (Yellow Horse et al., 2020).

The Impact of COVID-19 on Native American Communities

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed many disparities in minority communities. Many members of these communities live in multigenerational households, have greater reliance on public transportation, and have more front-line occupations with higher risk of COVID-19 exposure (Diop et al., 2021).

COVID-19 cases and death rates among Native Americans communities fluctuated through the course of the pandemic. Throughout the U.S., counties with higher population proportions of Native Americans had much higher death rates in May and June of 2021. Death rates tended to be lower after vaccine boosters became available (Bergmann et al., 2022). Structural factors such as lack of access to safe water for frequent hand washing and a shortage of personal protective equipment exacerbated difficulties related to infection control and prevention (Yellow Horse et al., 2020).

American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian persons had the highest incident cases and deaths per 100,000 population of any race/ethnicity in the United States. Throughout the country, Native Americans were more likely to be hospitalized and die than white patients. This remained true over every “surge” or sharp increase in cases (Bongiovanni et al., 2022).

San Francisco State University Associate Professor of Biology Wilfred Denetclaw, a Navajo man raised in the traditional Navajo way of life and teachings, shared the story of the Navajo Nation’s resilience during the pandemic. The Navajo government closed reservation borders during the height of the pandemic, instigated weekend curfews, and reached out to the University of California San Francisco and Health, Equity, Action, Leadership for health worker reinforcements.

When vaccines became available, former Navajo president Jonathan Nez advocated strongly for vaccinations using Navajo culture to emphasize the importance of vaccination as a protective shield against COVID-19. The community took the message to heart and now vaccination rates are among the highest across the United States (Rajan, 2022).

Did You Know. . .

At the start of the pandemic, the Navajo Nation had the highest COVID-19 infection rate anywhere in the United States. Intergenerational trauma, social isolation, lack of transportation, crowded multigenerational households, shortages in funding and supplies, widespread poverty, and an overworked healthcare workforce contributed to this disparity.

Now, the Navajo Nation is one of the safest places in America, due to its emphasis on collective responsibility, high vaccination rates, and public health measures. According to Jonathan Nez, [former] Navajo Nation president, “While the rest of the country were saying no to masks, no to staying home, and saying you’re taking away my freedoms, here on Navajo, it wasn’t about us individually,” he said. “It was about protecting our families, our communities and our nation.”

Rachel Cohen, How the Navajo Nation Beat Back COVID

The Nation, January 14, 2022

Historical Racism and the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Communities

The history of structural racism against Asians in the U.S. is untold. Since the arrival of the first wave of Chinese immigrants in the 1850s, the U.S. has viewed Asians as “perpetual foreigners.” Xenophobia led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first and only U.S. immigration law that targeted all people of a specific ethnic or national origin (Muramatsu and Chin, 2022).

The trauma associated with the forcible removal and internment of more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry in early 1942 has affected subsequent generations. The severe economic effects of forced removal, loss of homes and land, loss of education and career advancement, and years of confinement led to early deaths among those interned and loss of inheritance, homes, and land for their children (Nagata, Kim, Wu, 2019).

For Native Hawaiian and Pacific Inlanders (NHOPI), access to healthcare services is an ongoing issue. Among the nonelderly population, 13% of NHOPI people were uninsured in 2019. Compared to Asian and white Americans, NHOPI people are less likely to have private coverage and more likely to be covered by Medicaid, with half (50%) of NHOPI children being covered by Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) (Pillai, Ndugga, and Artiga, 2022).

Understanding the experiences of Asian Americans, as well as Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders is of particular importance, given the levels of racism and discrimination related to the COVID-19 pandemic. There has been a significant uptick in hate incidents against Asian people with many Asian Americans reporting deteriorating mental health due to both the pandemic and violence against Asian people (Pillai, Ndugga, and Artiga, 2022).

A 2021 Kaiser Family Foundation survey of Asian community health center patients found that 1 in 3 respondents reported experiencing more discrimination since the COVID-19 pandemic began and that many reported a range of negative experiences due to their race or ethnicity, ranging from receiving poor service to being verbally or physically attacked (Pillai, Ndugga, and Artiga, 2022).

The Development of the U.S. Healthcare System

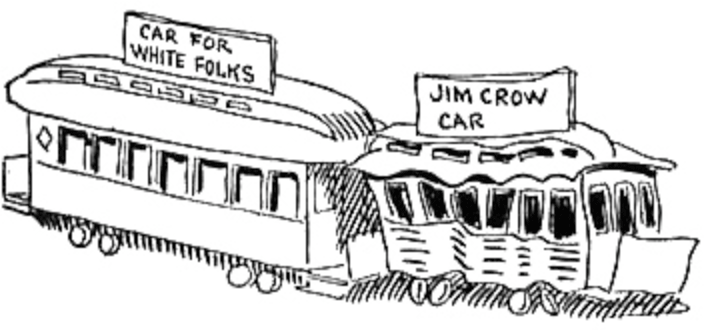

In the mid-1800s, partly due to the impact of the Civil War, the U.S. healthcare system experienced rapid growth and development. With the end of slavery and the onset of the Jim Crow era*, racist policies became embedded in the structuring and financing of the U.S. healthcare system (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022). After the Civil War—and continuing for more than a century—non-white people experienced a lack of services, discrimination, and the effects of a healthcare system that provided inferior healthcare to minorities, people of color, and Indigenous people.

*Jim Crow era: Statutes and ordinances established in 1874 to separate the white and Black races in the American South. Hospitals, and orphanages, and prisons were segregated as were schools and colleges.

In 1896, the landmark Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson ruled that “separate-but-equal” laws that segregated public facilities were legal. The services and facilities for Blacks and other minorities were consistently inferior, underfunded, and inconvenient as compared to those offered to whites—or did not exist at all. And while segregation was literal law in the South, it was also practiced in the northern U.S. via housing patterns enforced by private covenants, bank lending practices, and job discrimination, including discriminatory labor union practices (Howard University, 2018).

1904 caricature of “White” and “Jim Crow” rail cars by John T. McCutcheon. Public domain.

In the early 20th century, public hospitals--established in the late 18th and early 19th centuries by volunteers and religious organizations—began to grow and change. These changes were largely fueled by the growth of the labor movement and the rising demand for healthcare services among working-class Americans. The 1940s began an era of massive public health construction projects, funded through a combination of taxpayer dollars and charitable donations.

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 led to higher wages, benefits, and health insurance for those represented by unions. However, it did not apply to service, domestic, and agricultural workers, and it allowed unions to discriminate against racial and ethnic minorities employed in industries such as manufacturing. These workers were more likely to be relegated to low-wage jobs that failed to provide health insurance (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022).

In 1946, the federal government enacted the Hospital Survey and Construction Act (Hill-Burton Act), which provided funding for the construction of public hospitals and long-term care facilities. Although Hill-Burton mandated that healthcare facilities be made available to all without consideration of race, it allowed states to construct racially separate and unequal facilities (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022).

Federal programs such as the Medical Assistance for the Aged program (also known as Kerr-Mills), provided healthcare to the poor, but “were underfunded and few states participated, especially states with large populations of Black Americans” (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022). In 1960, Kerr-Mills extended medical benefits to a new category of “medically indigent” adults aged 65 or over. Eligibility and benefit levels were left largely to the States, meaning the poorer the state, the poorer the program. By linking medical assistance for the aged with public assistance, Kerr-Mills inadvertently created a program associated with social stigma and institutional biases. Nevertheless, Kerr-Mills served as an important precursor to Medicaid.

The Impact of Medicaid, Medicare, and the Affordable Care Act

With the development of Medicare and Medicaid programs, people who did not have health insurance began to have access to healthcare coverage. This played an important role in addressing limited healthcare access for racial and ethnic minority populations. Medicare funding provided powerful financial leverage for the early and proactive efforts of the Office for Civil Rights to secure the racial integration of hospitals, which encouraged hospitals, and providers to begin to address the needs of underserved communities.

Medicare and Medicaid reflect however, the racial paradox of the safety net: It is a product of a structurally racist health system in which racial and ethnic minority groups were disproportionately excluded from employer-sponsored health insurance, yet it is also an important, if limited, tool for filling this gap (Yearby, Clark, & Figueroa, 2022).

Medicaid remains the largest public health insurance provider in the U.S., with more than 80 million enrollees (Commonwealth Fund, 2022). Because Medicaid is highly fragmented and decentralized—with the federal government, states, and even localities making decisions about how to fund, design, and administer it—there are numerous places where inequities can occur including benefits offered, waivers required for work-reporting requirement, provider payments, outreach efforts, and program administration (Commonwealth Fund, 2022).

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are the primary sources of coverage for many children of color. Medicaid covers about 30% of Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander nonelderly adults, and more than 20% of Hispanic nonelderly adults, compared to 17% of their white counterparts (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

The Affordable Care Act (2014) expanded Medicaid to adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level. Medicaid expansion has been linked to increased access to care, improvements in some health outcomes, and reductions in racial disparities in health coverage (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

In the states that have not yet adopted Medicaid expansion, more than 2 million people fall into a coverage gap, with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to qualify for marketplace subsidies. Nearly 60% of people in the coverage gap are people of color. Uninsured Black adults are more likely than their white counterparts to fall into the gap because most states that have not expanded Medicaid are in the South where a larger share of the Black population resides (Guth and Artiga, 2022).

The American Rescue Plan Act, enacted in March 2021, includes a temporary fiscal incentive to encourage states to take up the expansion. The Build Back Better Act would temporarily close the Medicaid coverage gap by making low-income people eligible for subsidized coverage under the Affordable Care Act in states that have not expanded Medicaid (Guth and Artiga, 2022). In Kentucky, after the state accepted Medicaid expansion, there has been a 58% decrease in the number of uninsured people (Healthinsurance.org, 2023).