For healthcare providers, identifying warning signs and risk factors, accessing services, and providing evidence-based care are key challenges. In the United States, about 33% of people who took their life were in contact with mental health services the year before their death. Nearly half of those were seen in primary care the month before death (McCabe et al., 2017). Because of these sobering statistics it is critically important that healthcare providers be educated about and aware of risk factors and warning signs associated with suicidal behaviors.

Warning Signs

Warning signs are actions or behaviors that are observed by or reported to another, and indicate risk for suicide within minutes, hours, or days. Warning signs can be acute and urgent or simply red flags for concern.

About 80% of people who attempt suicide show some sort of warning sign. Knowing and recognizing these signs can help family and friends take action before suicidal thinking turns into action. Recognition of warning signs provides an opportunity for early assessment and intervention.

Widely accepted general suicide warning signs include:

- Anxiety, agitation, sleeplessness

- Feeling that there is no reason to live

- Rage, anger, or aggression

- Recklessness

- Increased alcohol or drug abuse

- Withdrawal from family and friends

- Abrupt mood swings

- Hopelessness, feeling trapped (USDVA, 2019)

Three specific suicide warning signs require immediate attention:

- Communicating suicidal thought verbally or in writing, especially if this is unusual or related to a personal crisis or loss

- Seeking access to lethal means such as firearms or medications

- Demonstrating preparatory behaviors such as putting affairs in order (USDVA, 2019)

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that makes it more likely for a person to develop a disorder. Although suicide is rare in comparison to its associated risk factors, increased risk has been associated with prior attempts, emotional and financial loss, illness, hopelessness and isolation, childhood experiences, and access to lethal means. Increased risk is also associated with relationship, community, and societal issues such as local epidemics of suicide, stigma, lack of medical services, family history of suicide, and certain cultural and religious beliefs.

Mental Illness

Although suicidal behavior is strongly associated with mental disorders, no linear relationship exists; the vast majority of people with mental disorders do not experience suicidal behavior. Because of this, psychiatric disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior have only limited predictive power (Brüdern et al., 2018).

Suicide is nevertheless overrepresented in people with mental illness, and a large percentage of suicide victims have a diagnosable mental health disorder. The odds for suicide in people with severe depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder are approximately 3 to 10 times that of the general population, with a higher risk in males than females. Despite this, suicide occurs in only 3% to 5% of these cases (Fosse et al., 2017).

A poor social network and social withdrawal, command hallucinations,* delusions, and mental disorders other than depression are associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviors in people with mental illness. This can include bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, coexisting physical illness, family history of mental illness, multiple admissions to inpatient treatment, unplanned discharge, and prescription of antidepressants (Fosse et al., 2017).

*Command hallucinations are hallucinations in the form of commands; they can be auditory or inside of the person's mind or consciousness. The contents of the hallucinations can range from the innocuous to commands to cause harm to the self or others.

For patients admitted to a specialized mental health facility, there is a 50- to 200-times increased risk of suicide compared to the population at large. In two meta-analyses that included 42 studies and close to 3,500 suicide completers, central suicide risk factors were:

- Prior suicide attempts

- History of deliberate self-harm

- Family history of suicide

- History of suicidal ideation

- Depression, hopelessness

- Agitation

- Social or relationship problems (Fosse et al., 2017)

Although both evidence and common sense suggests that suicides can be avoided with effective treatment of mental disorders, most people in need do not receive adequate treatment. This is because mental conditions are under-recognized, which limits the potential to identify and appropriately treat individuals at risk for suicide.

Medical Issues, Stress, and Illness

Certain medical conditions, chronic illness, and stressful life events are associated with an increased risk for suicidal behaviors. Chronic pain, ongoing stress, cognitive changes, loss of mobility, sensory changes, and difficulty making decisions and solving problems are some of the many challenges related to long-term illness and disability. Physical and psychological trauma can also be risk factors for suicide.

Co-morbid conditions may increase the likelihood that a suicide attempt becomes a completed suicide; for example, if a person with a chronic condition such as hepatitis C swallows a bottle of acetaminophen, they are likely to suffer severe liver damage. By the same token, a person with severe anemia may not survive a suicide attempt involving a significant loss of blood.

Substance Use Disorders

Every year about 650,000 people receive treatment in emergency departments (EDs) following a suicide attempt. More than 40% of these admissions involve drug-related suicide attempts, and many involve a prescription drug or over-the-counter (OTC) medication. Substance use disorders are a strong risk factor for suicide attempts and suicide. Indeed, suicide is a leading cause of death among people who misuse alcohol and drugs (SAMHSA, 2016).

Alcohol misuse or dependence is associated with a suicide risk that is 10 times greater than the suicide risk in the general population, and individuals who inject drugs are at about 14 times greater risk for suicide. Acute alcohol intoxication is present in about 22% of suicide attempts (SAMHSA, 2016). Depression—a common co-occurring diagnosis among people who abuse substances—also confers risk for suicidal behavior (CSAT, 2015).

Did You Know. . .

The number of ED visits for drug-related suicide attempts increased 41% overall from 2004 to 2011 and more than doubled among people age 45 to 64 (Crane, 2016).

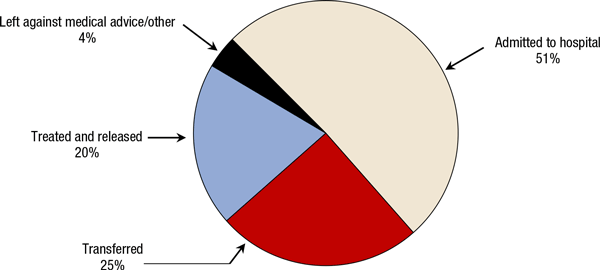

A person admitted to the ED at acute risk for suicide and who is also intoxicated by drugs or alcohol should be kept under observation and assessed for suicide risk when no longer intoxicated or in acute withdrawal. Following assessment in the ED, about half of these patients are admitted to the hospital, about a quarter are transferred to another healthcare facility, and slightly less than a quarter are discharged after being treated. About 4% leave against medical advice or die in the ED (Crane, 2016).

Outcomes of ED Visits Involving Drug-Related Suicide Attempt (2004 to 2011)

Source: Crane, 2016.

Substance Use Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), no longer uses the terms substance abuse and substance dependence, rather it refers to substance use disorders, which are defined as mild, moderate, or severe, determined by the number of diagnostic criteria met by an individual.

Substance use disorders occur when the recurrent use of alcohol and/or drugs causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of substance use disorder is based on evidence of impaired control, social impairment, risky use, and pharmacologic criteria.

Most Common Substance Use Disorders in the U.S.

- Alcohol use disorder

- Tobacco use disorder

- Cannabis use disorder

- Stimulant use disorder

- Hallucinogen use disorder

- Opioid use disorder

Source: SAMHSA, 2015.

Even when a person is in treatment for a substance use disorder, the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts remains high. This is also true for those who have at one time been in treatment (CSAT, 2015).

Abstinence is a primary goal of any client with a substance use disorder and suicidal thoughts or behaviors. For most clients abstinence reduces risk, although some individuals remain at risk even after achieving this goal. This can include patients with:

- Independent depression

- Difficulties that promote suicidal thoughts

- Personality disturbances such as borderline personality disorder

- History of trauma (such as sexual abuse)

- Major psychiatric illness (CSAT, 2015)

Did You Know. . .

The number of substances used seems to be more predictive of suicide than the types of substances used.

One of the reasons alcohol and drug misuse significantly affects suicide rates is the disinhibition and impulsivity that occurs when a person is intoxicated. Impulsivity and disinhibition are overarching issues related to suicidal behaviors. In fact, angry impulsivity has been repeatedly identified as a common risk factor. Although impulsivity is found in a wide range of diagnoses, it is highly associated with bipolar disorder, substance abuse, and certain personality disorders, as well as a history of early child abuse (Fawcett, 2012).

Immigrants and Refugees

For people migrating to the United States, stress associated with migration can be a risk factor for suicidal ideation. Ending ties with their country of origin, loss of status and social networks, language barriers, unemployment, financial problems, a sense of not belonging, and feelings of exclusion can lead to depression, anxiety, PTSD, alcohol and drug abuse, loneliness, and hopelessness (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

Refugees, one of the most vulnerable groups of immigrants, may be fleeing war, torture, and persecution, and suffering with PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Lack of adequate preparation, the way in which refugees are received in the destination country, poor living conditions, lack of social support, and isolation add to these vulnerabilities. Refugees may also feel guilty for leaving loved ones at home. The sense of guilt, together with isolation and trauma, may be risk factors for suicide (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

Migration poses a risk not for the families who remain in the country of origin. For example, it has been observed that the next of kin of Mexican emigrants to the United States were at greater risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than Mexicans without a family history of immigration. Immigration can weaken family ties, lead to feelings of loneliness and insecurity, and increase the risk of suicide among family members who remain at home (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

Immigrants from predominantly collectivist societies may face serious problems of adaptation due to a real or perceived lack of social support, a disparity between expectations and reality, and low self-esteem. Many immigrants undergo radical changes in their social status and may also be subject to discrimination. This could be an additional risk factor for suicide, as evidenced by one of the U.S. studies where immigrants’ suicide rates were positively correlated with the negative words used by the majority to describe their ethnic group (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

In most studies conducted in Europe, America, and Australia, the highest risk of suicide was found in immigrants from northern Europe (including the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Finland), and Eastern Europe (especially from Russia and Hungary). The lowest risk was found in immigrants from southern Europe and the Middle East (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

For immigrants from Asian countries, the risk of suicide seems generally low for men but appreciably higher for women. The rates vary not only in relation to the country of origin but also for the gender of the immigrant. For example, in a study conducted in the United States, Asian, black, and Hispanic men had the lowest risk of suicide, while non-Hispanic white and Asian women had higher risk than the host population (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

The high suicide rates among immigrants from Northern and Eastern Europe might be partly explained by the high alcohol consumption typical of these countries. For example, there is a significant correlation between alcohol consumption and suicide in Finland; Finnish immigrants who died by undetermined causes of death in Sweden also tend to have high alcohol levels in their blood. A similar trend was found in Russia, where suicide rates related to alcohol abuse are very high, and among Russian immigrants who died by suicide in Estonia (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

The low rates of suicide among immigrants from southern Europe, the Middle East, and Asia may be due to some protective social factors, such as the strong influence of traditional values, family, and religious beliefs. These countries are more collectivist, have strong family ties, and a strong group identity outside their country of origin. Both in Catholic and Muslim countries, religion may be a strong deterrent to suicide, which is considered a sin in the Catholic religion and is forbidden by Islamic law. The protective role of religion could also depend on the ties with the religious community, which might represent a strong source of social support (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

Among asylum seekers, those at higher risk for suicide are young, male, low income, with past traumatic experiences and lack of social support. Refugees and asylum seekers often have several of these risk factors (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

Diagnostic Dilemma: Psychosis or PTSD

A 32-year-old black African, Muslim woman with a history of both PTSD and psychosis presented to mental health services for the first time with a history of auditory and visual hallucinations, persecutory delusions, suicidal ideation, recurring nightmares, hyper-arousal, and insomnia. She reported seeing blood on the walls, men in white following her, and hearing voices saying that some men were coming to get her. These symptoms were worse at night. She became very distressed and troubled to the point of wanting to end her life.

Her background history suggested co-morbid PTSD. Twelve years before, she saw her family (parents, sisters and brother) being killed during the civil war in her birth country in Africa. Her clinical PTSD symptoms, such as the recurring nightmares, hyper-arousal, and insomnia, began shortly afterwards. Eight years later, she entered the United Kingdom as an asylum seeker.

During her first few years in the U.K., she had no social support, was unable to speak English, experienced homelessness, and was unsuccessful in gaining asylum. Her auditory and visual hallucinations and persecutory delusions started at this time. A few months before her first contact with mental health services, her psychotic symptoms and PTSD features became more frequent and intense. With no stable relationship, she became pregnant and visited her general practitioner, who referred her to our first-episode psychosis unit.

Upon admission to the psychosis unit, she presented as kempt yet she appeared distressed. She was withdrawn and quiet and there was some delay in her responses to questions. She was tearful and her mood was low but reactive. She described vivid and clear auditory and visual hallucinations and persecutory delusions. Her medical psychiatric, personal, and family histories were unremarkable. A physical examination, neurologic examination and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan were normal. The results of routine blood investigations were in the normal range, and a pregnancy test was positive. At the clinical interview, she clearly fulfilled the criteria for PTSD and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Because of the intensity of her symptoms, her distress and suicidal ideation, the mental health team recommended ongoing hospitalization. She was started on trifluoperazine* (5 mg/day) and cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis. She also started a prenatal follow-up. She self-reported a partial improvement in her clinical picture—and her psychotic symptoms gradually resolved over a three-week period, although they occasionally resurfaced when she was under stress or whenever her medication compliance lapsed.

* Trifluoperazine (Stelazine) is a typical antipsychotic primarily used to treat schizophrenia. It is in a class of drugs called phenothiazines.

She was discharged from hospital and is now living in temporary accommodations funded by local services and waiting for her asylum re-application to be processed. She continues to have ongoing PTSD symptoms, associated with the initial tragic event, as persistent remembering of the stressor event with recurring and vivid memories, nightmares, hyper-arousal, and initial insomnia. She also avoids circumstances resembling the initial stressor event, such as wars and violence.

Source: Coentre & Power, 2011.

Documenting Risk

Documentation should describe the gathering of information, whether or not a consultation is needed, a description of the action taken by the healthcare provider to address the patient’s risk, and what steps were taken to follow up. Documentation provides a written summary of any steps taken, along with statements that show the rationale for the plan. The plan should make good sense in light of the seriousness of risk (CSAT, 2015).

Gathering information involves collecting relevant facts. Screening questions should be asked of all new patients when you note warning signs and any time you have a concern about suicide, whether or not you can pinpoint the reason. Inquiries start with open-ended questions that invite the client to provide more information. Followup questions are then asked to gather additional, critical information.

Consultation is a formal process whereby information and advice are obtained from (a) a professional with clear supervisory responsibilities, (b) a multidisciplinary team that includes such people, and/or (c) a consultant experienced in managing suicidal clients who has been vetted by your agency for this purpose. Immediate supervision or consultation should be obtained when clients exhibit direct suicide warning signs or when, at intake, they report having made a recent suicide attempt. Substance abuse relapse during treatment is also an indication for supervisory involvement for clients who have a history of suicidal behavior or attempts.

Caveat

Do not make a judgment about the seriousness of suicide risk or try to manage suicide risk on your own unless you have an advanced mental health degree and specialized training in suicide risk management, and it is understood by your agency that you are qualified to manage such risk independently.

Taking responsible action means your actions should make good sense in light of the seriousness of suicide risk. Seriousness is defined as the likelihood that a suicide attempt will occur and considers the potential consequences of an attempt. Judgments about the degree of seriousness should be made in consultation with a supervisor or a treatment team, not by a healthcare provider acting alone.

Suicide prevention efforts are ongoing rather than one-time actions requiring consistent followup. A team approach is essential, which requires a healthcare provider to follow up on referrals and coordinate with other providers in an ongoing manner.

The following case example highlights the importance of documentation using the four-step process: (1) gather information, (2) access supervision or consultation, (3) take responsible action, and (4) follow up.

Fernando, Iraqi War Veteran

This case is based on a progress note for Fernando, a 22-year-old Hispanic male and Iraq war veteran, who was doing well in treatment for dependence on alcohol and opiates, but had missed his group therapy sessions and had not returned phone calls for the past 10 days. This situation occurred in a substance abuse clinic within a hospital and required immediate supervision and interventions of high intensity.

Step One: Gather Information

Fernando came in, unannounced at 10:30 a.m. today and reported that he relapsed on alcohol and opiates 10 days ago and has been using daily and heavily since. Breathalyzer was 0.08, and he reported using two bags of heroin earlier this morning. He reported that he held his loaded rifle in his lap last night while high and drunk, contemplating suicide.

Step Two: Access Supervision or Consultation

Upon consultation with a supervisor, it was determined that Fernando was at acute risk of self-harm, and acute emergency intervention was needed because of intense substance use, suicidal thoughts with a lethal plan, and access to a weapon.

Step Three: Take Responsible Action

At 11:00 a.m., a hospital security guard and the nurse who had evaluated Fernando escorted him to the ED, where he was checked in. He was cooperative throughout the process.

Step Four: Follow-up

Dr. McIntyre, the ED physician, determined that Fernando required hospitalization. He is currently awaiting admission. This evaluating nurse will follow up with the hospital unit after he is admitted and will raise the issue of his access to a gun.

Source: CSAT, 2015.