People who are exposed to opioids—including prescribed opioids—are at increased risk of long-term use and of developing an opioid use disorder. Surveys of people with opioid use disorders often identify prescription opioids as the “initiating” opioid. The importance of the admonition to “keep opioid-naive patients opioid naive” cannot be overstated (Tsai et al., 2019).

Healthcare professionals who prescribe or administer opioids must keep in mind the potential for misuse and abuse. They must be well informed about the appropriate use and cautions for opioid misuse and must be able to recognize effectiveness, side effects, overdose symptoms, and abuse in patients and in other healthcare professionals.

Primary and secondary prevention practices include reducing incautious and long-term opioid prescribing; preventing diversion; and identifying patients who may be at risk for, or who have already developed, an opioid use disorder. Thoughtful and cautious opioid prescribing is a key part of prevention (Tsai et al., 2019).

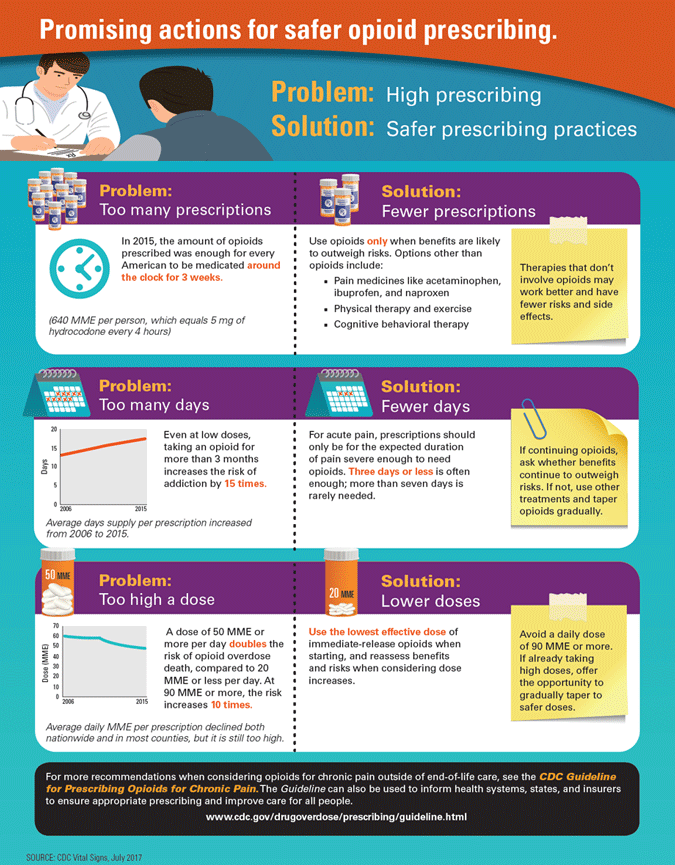

Over the last decade, opioid prescribing has been in decline, especially the incidence of initial opioid prescriptions for opioid-naive patients. Despite this favorable trend, drug overdose mortality has continued to increase, with nonpharmaceutical fentanyl and its analogues increasingly associated with drug overdose deaths (Tsai et al., 2019). Improving the way opioids are prescribed can ensure patients have access to safer, more effective chronic pain treatment while reducing the number of people who misuse or overdose from these drugs.

Guidelines for Chronic Pain

In response to the opioid crisis, in 2016 CDC developed the Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. The guideline included a recommendation to limit opioids for acute pain in most cases to 3 to 7 days. This recommendation was based on evidence showing an association between use of opioids for acute pain and long-term use. In the last several years, more than 25 states have passed laws restricting prescribing of opioids for acute pain (AHRQ, 2020, January 2).

The Guideline provides recommendations for primary care clinicians who are prescribing opioids for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care. It addresses 1) when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain; 2) opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation; and 3) assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use (Dowell et al., 2016).

Key Points

- Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain.

- The lowest effective dose of an opioid is recommended.

- For chronic pain, non-opioid therapies are preferred.

- Immediate-release opioids are preferred over extended-release/long-acting opioids.

Evaluate the benefits and harms within 1 to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy.

Source: NIDA, 2017.

In addition:

- Use a Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) to determine concurrent opioid use.

- Use urine drug test screening to test for concurrent illicit drug use.

- Avoid concurrent prescribing of other opioids and benzodiazepines if possible.

- Offer evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorders. (NIDA, 2017)

On January 1, 2018, the Joint Commission implemented revised pain assessment and management standards. The new standards state that hospitals must identify pain assessment and pain management, including safe opioid prescribing, as an organizational priority. They must:

- Involve medical staff in performance improvement activities to improve quality of care, treatment, and patient safety.

- Assess and manage the patient’s pain and minimize the treatment risks.

- Collect, compile, and analyze data to monitor performance. (Joint Commission, 2017)

Source: CDC, 2017, July 6.

Rhode Island Prescribing Regulations

In Rhode Island, before prescribing an opioid, healthcare providers must talk to patients about the risks of taking opioid pain medications as prescribed. This conversation is an opportunity to thoughtfully consider risks, potential benefits, and must include the following topics:

- Risks of developing physical and psychological dependence which may lead to harmful use, addiction, overdose, and/or death;

- Risks associated with concurrent use of alcohol or other sedating medications, such as benzodiazepines;

- Impaired ability to safely operate any motor vehicle;

- Patient’s responsibility to safeguard all opioid medications in a secure location;

- Patient’s ability to safely dispose of unnecessary or unused opioids;

- Alternative treatments for managing pain; and

- Risks of relapse for those who are in recovery from substance dependence. (RIDOH, 2018)

For patients with chronic pain, opioids are associated with small beneficial effects versus placebo but are associated with increased risk of short-term harms and do not appear to be superior to nonopioid therapy. Evidence on intermediate-term and long-term benefits is limited, and additional evidence confirms an association between opioids and increased risk of serious harms that appears to be dose-dependent (AHRQ, 2019).

Rhode Island has a statewide Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). It collects data for controlled substance prescriptions (Schedules II–V, or opioid antagonists) in a centralized database. These data can then be used by prescribers and pharmacists in the active treatment of their patients. Under Rhode Island regulations, information about all transactions for controlled substances dispensed in Rhode Island must be reported.

The Dilemma in Acute Pain Management

Acute pain occurs in response to noxious stimuli and is normally sudden in onset and time limited. It usually lasts for less than 7 days but can extend up to 30 days; for some conditions, acute pain episodes may recur periodically. In some patients, acute pain persists to become chronic.

The dilemma in the medical management of acute pain lies in selecting an intervention that provides adequate pain relief, improves function, and facilitates recovery, while minimizing adverse effects and avoiding overprescribing of opioids. When acute pain is adequately treated, it may prevent the transition to chronic pain (AHRQ, 2020, January 2).

Many factors influence acute pain management. For example, postoperative pain is usually managed with multimodal strategies in a monitored setting prior to discharge. By contrast, treatment of pain in an outpatient setting can be more difficult. A treatment that is effective for one acute pain condition and patient in a particular setting may not be effective in others (AHRQ, 2020, January 2).

Reducing the Use of Opioids

Effective pain management should focus on avoiding opioid-only therapy and reducing the doses used to treat acute pain. This approach involves the administration of various opioid and non-opioid agents that act on different sites, resulting in a synergistic* and additive** effect. The goal is to reduce opioid-related adverse drug events and their costs, as well as the risks of opioid abuse or dependence (Carter et al., 2020).

*Synergistic: combining the drugs that lead to a larger effect than expected from a single drug.

**Additive: Occurs when two or more drugs combine to produce an effect greater than the effect of either drug taken alone.

Non-opioid pharmacologic therapies include acetaminophen and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). When NSAIDs and/or acetaminophen are included with opioids in treatment regimens for pain relief, an opioid-sparing* effect has been demonstrated (Carter et al., 2020).

*Opioid-sparing: the use of drugs that allow a patient to feel a similar level of pain relief while taking fewer opioids.

Cannabis may have an opioid-sparing effect whereby a smaller dose of opioids provides equivalent analgesia when paired with cannabis. A growing number of studies involving patients who use cannabis to manage pain demonstrate reductions in the use of prescription analgesics along with favorable pain management outcomes. However, there is a lack of research from real-world settings on the opioid-sparing potential of cannabis among high-risk individuals who may be engaging in frequent illicit opioid use to manage pain (Lake et al., 2019).

Avoiding Stigma

The primary problem with the opioid epidemic is simple: It is easier to get high than it is to get help. People who need substance use treatment sometimes do not have access to treatment. Stigma surrounding substance use disorders remains high.

Negative attitudes toward people with opioid use disorders undermine secondary prevention responses. People taking prescription opioid medications for chronic noncancer pain who experience physiologic dependence may be marked with the same labels as people with OUDs and experience difficulties obtaining care. Healthcare professionals’ stigmatizing beliefs can lead to suboptimal care, a form of enacted stigma that reduces patients’ engagement with drug treatment (Tsai et al., 2019).

In some instances, care providers may maintain overly rigid and non-beneficial care policies that lack respect for patient autonomy. They may deploy punitive care terminations in response to policy violations or positive urine toxicology screening (Tsai et al., 2019).

In the years since CDC published its new opioid-prescribing guideline, stigma enactments have included the imposition of rigid dosage or duration caps or initiation of noncollaborative tapers with established patients, escalating potential harms and transition to nonprescription opioids. Enacted stigma has also been directly associated with nonfatal overdose (Tsai et al., 2019).

To prevent stigmatizing a person, avoid labels (“addict,” “junkie,” or “drug user”). Understand that drug use falls along a continuum and that substance misuse is often linked to trauma. Additionally:

- Use “person first” language.

- Be aware of unintentional bias.

- Reflect on your own experiences.