An Opioid Overdose

Source: National Library of Medicine.

There has been a dramatic increase in the acceptance, use, and abuse of prescription opioids for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain, despite serious risks and lack of evidence about their long-term effectiveness. Prescription opioid overdose deaths are on the rise and remain 4 times higher than in 1999 (CDC, 2021, January 25).

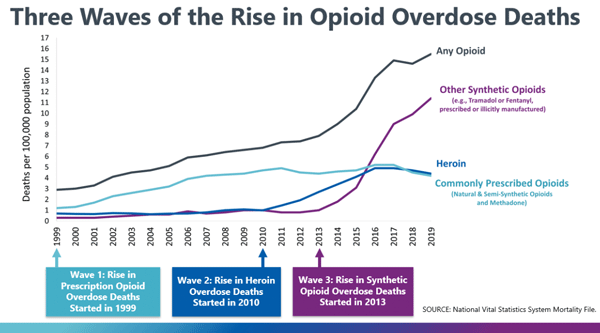

Three Waves

In the United States the rise in opioid overdose deaths has been described as occurring in three distinct waves. The first wave began in the early 1990s, with increased prescribing of opioids. Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (natural and semi-synthetic opioids and methadone) began to increase around 1999. The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin (CDC, 2020, September 4).

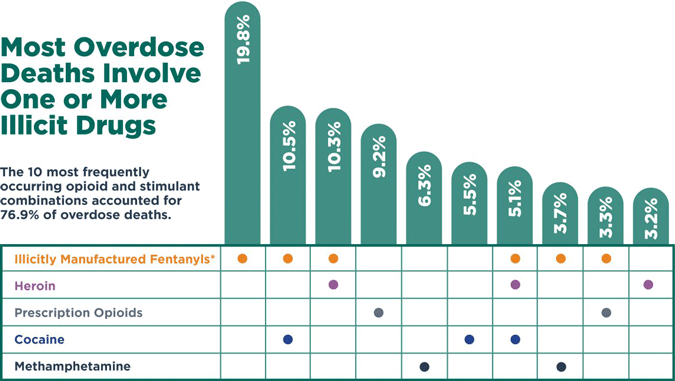

The third wave began in 2013, with significant increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl. The market for illicitly manufactured fentanyl continues to change, and it is used in combination with heroin, counterfeit pills, and cocaine . During the third wave, nearly 85% of overdose deaths involved illicitly manufactured fentanyl, heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine (alone or in combination) (CDC, 2020, September 4).

*IMFs include fentanyl and fentanyl analogs.

Source: CDC, 2020, September 4.

Illicit designer drugs have been particularly difficult to identify and track. Amateur and professional chemists can quickly reproduce an illicit drug, alter its potency, and flood the market with modified compounds undetectable by most known tests. Often little is known about the effects of these drugs because their chemical structures are modified so rapidly and so often that it is impossible for researchers and law enforcement to keep up with the changes.

Source: CDC, 2020 September 3.

Most-Abused Prescription Drugs

Most-Abused Prescription Pain Relievers, Nationally

Hydrocodone

Oxycodone

Codeine

Tramadol

Buprenorphine

Morphine

Oxymorphone

Hydromorphone

Fentanyl

Source: SAMHSA, 2020, May.

Overall, the three classes of most-abused prescription drugs are:

- Opioids that include oxycodone (Percocet, Tylox, OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lortab), and methadone (Dolophine).

- Central nervous system depressants that include butalbital (Fiorinal/Fioricet), diazepam (Valium), and alprazolam (Xanax).

- Stimulants that include methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (Adderall). (NIDA, 2020, June)

The burden of the opioid epidemic, involving both the misuse of prescribed opioids and the use of illicit opioids, is not uniform across the United States. Drug poisoning mortality and opioid consumption rates vary significantly by state and region, with drug poisoning rates highest in the Southwest and lowest in the Midwest (Yang et al., 2020).

Sales of opioid analgesics, which are prone to abuse, have also varied significantly by state. For example, prescription drug abuse of oxycodone has been unevenly concentrated in eastern and southeastern states with a pattern of migration from the Northeast and Appalachia toward the Southeast and West (Yang et al., 2020).

Opioid prescribing remains high and inconsistent across the United States and varies widely from county to county. Some characteristics of areas with higher opioid prescribing:

- Small cities or large towns

- Areas with a higher percentage of white residents

- Areas with more dentists and primary care physicians

- Areas with more people who are unemployed or uninsured

- Areas with more people with diabetes, arthritis, or disability (CDC, 2017, July 6)

Overdose Deaths in Rhode Island

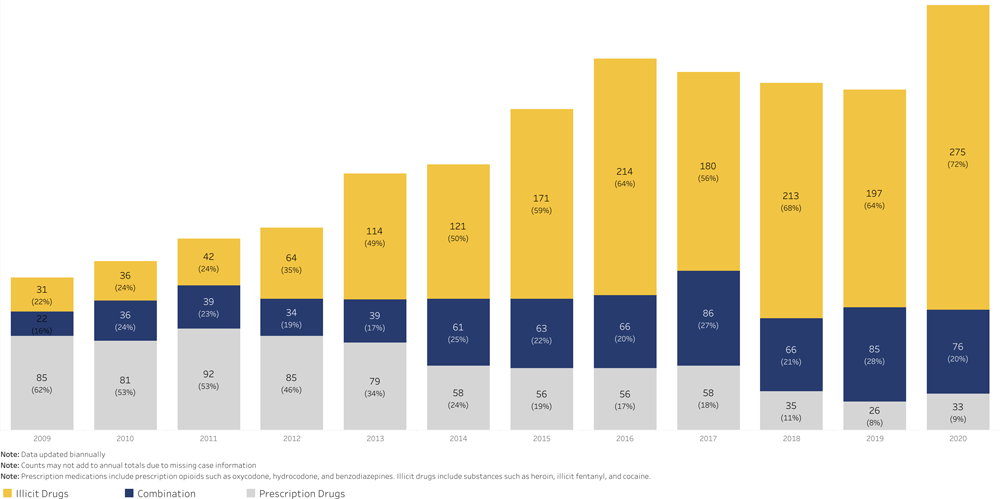

Every county in Rhode Island has been affected by the opioid crisis, but five cities have experienced a higher number of overdose deaths: Cranston, Pawtucket, Providence, Warwick, and Woonsocket. Although the state’s overdose crisis started with prescription drugs, overdose deaths from this source have leveled. Deaths from illicit drugs—such as heroin and fentanyl—are on the rise. Strikingly, about 75% of people who die of an overdose in Rhode Island are men (Prevent Overdose RI, 2020a).

Rhode Island Overdose Deaths by Drug Type, 2009–2019

Source: Prevent Overdose RI, 2020a.

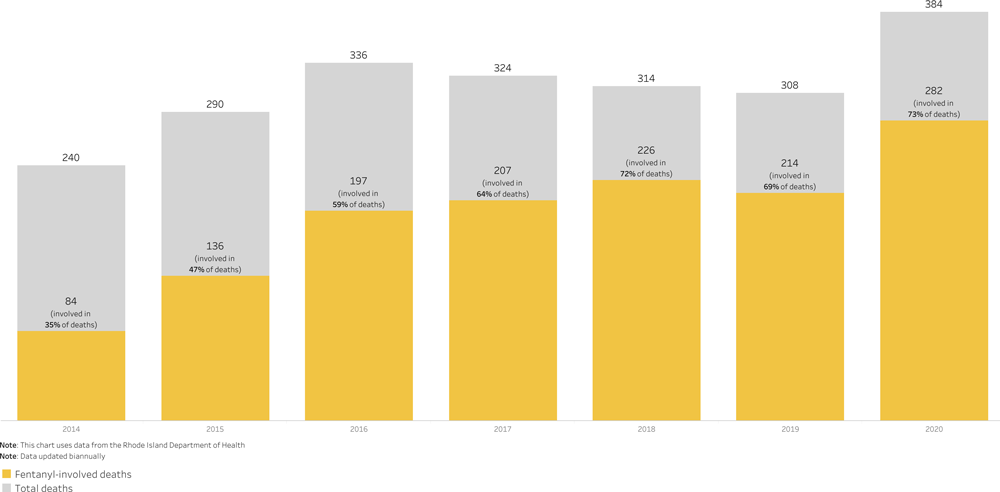

Fentanyl continues to pose the greatest threat and has worsened Rhode Island’s overdose crisis. The number of overdose deaths related to illicit fentanyl has increased by almost 30-fold since 2009. From January to October of 2020, over 70% of overdose deaths have involved illicit fentanyl (Prevent Overdose RI, 2020a).

Overdose Deaths Due to Fentanyl, 2014–June 2020

Source: Prevent Overdose RI, 2020a.

Reversing the Tide

The Rhode Island Department of Health has implemented initiatives to help reverse the effects of the opioid epidemic. Unfortunately, in about 60% of cases, help is available but it is not offered by healthcare providers.

The Drug Overdose Prevention Program advances and evaluates comprehensive state-level interventions for preventing drug overuse, misuse, abuse, and overdose. Prescriber Education Sessions provide one-on-one or small-group sessions covering resources, naloxone education, and best practices. The Recovery and Hope Hotline connects counselors licensed in chemical dependency who offer support, tips, self-help tools, and referrals to opioid use disorder treatment services.

Case: Bob, Construction Worker

Bob, a 45-year-old construction worker was being treated in an acute care hospital for a broken femur and a low-back, work-related injury. The nurses offered narcotic analgesics around the clock,* as ordered, to keep Bob comfortable.

*Rather than offer any other comfort measures, it was easier to administer the narcotic that kept him from using the call light repeatedly.

After he was discharged, Bob followed up with his primary care physician, who initially prescribed oxycodone and muscle relaxers in a limited supply and without refills, per standard practice. Within one month, Bob returned complaining of constant pain, and he was given a new prescription for oxycodone. The monthly visits became routine, without additional assessments. No alternative modalities were discussed or offered, and no narcotic use contract was written. Prescriptions continued to be written and filled.

Eventually, the medications offered no further pain relief and Bob began supplementing with legal marijuana to provide relief for the initial back pain and for the progressive physical craving for the opioid. He visited several other physicians to increase his supply and none of the providers were aware of his multiple visits and duplicated prescriptions.

Bob eventually advanced to street heroin and ultimately overdosed on the combination of opioids that took his life.

What could have been done to avoid this needless loss of life?

What is the role of healthcare professionals in the prescribing and monitoring of opioid drugs?

What is the nurse’s role in the opioid epidemic?

What prevention and treatment strategies are available?