Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens following contact with human blood and body fluids is a serious concern for healthcare workers globally. Hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are the three leading causes of occupationally related bloodborne infections among healthcare workers (Auta et al., 2018).

Transmission Ports for Bloodborne Pathogens

Source: Google Images.

The need to protect healthcare workers from bloodborne exposures resulted in the publication of the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard by OSHA in 1991.

Part of the Standard is the requirement that every healthcare worker who may have contact with body fluids on the job must receive specific annual education. This education includes:

- Instruction in the basics of infection control and prevention

- Bloodborne pathogens training

- Instruction in modes of transmission, needlestick precautions, and contact precautions

The risk of infection by a bloodborne pathogen varies. Factors influencing the risk of infection include whether the exposure was from a hollow-bore needle or other sharp instrument to non-intact skin or mucus membrane (such as the eyes, nose, and/or mouth), the amount of blood involved, and the amount of pathogen present in the source person's blood (OSHA, 2021).

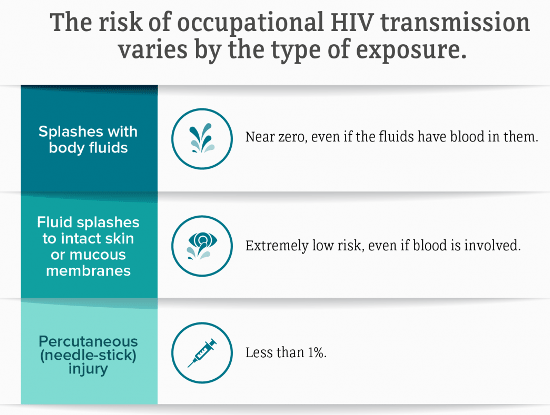

Risk of HIV Infection

Occupational HIV transmission is extremely rare. The risk of HIV infection to a healthcare worker through a needlestick is less than 0.23%. The risks of HIV infection through splashes of blood to the eyes, nose, or mouth is even smaller—approximately 1 in 1,000. There have been no reports of HIV transmission from blood contact with intact skin.

There is a theoretical risk of blood contact to an area of skin that is damaged, or from a large area of skin covered in blood for a long period of time. The CDC has reported fifty-eight documented cases of occupational HIV transmission to healthcare workers in the U.S., with no confirmed cases since 1999 (CDC, 2019).

Source: CDC.

Risk of Hepatitis B and C Infection

Although becoming infected with hepatitis B (HBV) from a needlestick is more common than HIV for healthcare workers, the risk has decreased considerably since the implementation of an HBV vaccine the early 1980s. For healthcare workers vaccinated against hepatitis B, infection from a single needle stick is very low—about 1 in 300. For a healthcare worker not vaccinated against HBV, the risk of infection can be as high as 30%.

The risk is 2% to 19% if the source person tests positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg). If the source person is HBsAg-positive and HBeAg-negative, there is a 1% to 6% risk of getting HBV unless the person exposed has been vaccinated (Lewis et al., 2015).

The risk of getting hepatitis C (HCV) from a needlestick is 1.8%. The risk of getting HBV or HCV from a blood splash to the eyes, nose, or mouth is possible but believed to be very small. Approximately three million healthcare workers per year are exposed to HBV and HBC through occupational instrument injuries. There are no exact estimates on how many healthcare workers contract HCV from an occupational exposure, but the risk is considered low (Coppola et al., 2016).

Treatment After a Potential Bloodborne Exposure

As soon as safely possible after a potential exposure, wash the affected area with soap and water. Application of antiseptics is not a substitute for washing. Remove any potentially contaminated clothing as soon as possible. Be familiar with existing protocols and the location of emergency eyewash or showers and other stations within your facility.

If there is exposure to the eyes, nose, or mouth, flush thoroughly with water, saline, or sterile irritants. The risk of contracting HIV through this type of exposure is estimated to be 0.09%.

If a sharps injury occurs, wash the exposed area with soap and water. Do not “milk” or squeeze the wound. There is no evidence that using antiseptics like hydrogen peroxide will reduce the risk of transmission for any bloodborne pathogens; however, the use of antiseptics is not contraindicated. If the wound needs suturing, emergency treatment should be obtained. The risk of contracting HIV from this type of exposure is estimated to be 0.3%.

Exposure to saliva is not considered substantial unless there is visible contamination with blood. If exposed, wash the area with soap and water, and cover with a sterile dressing as appropriate.

Did you know. . .

For human bites, the clinical evaluation must include the possibility that both the person bitten and the person who inflicted the bite were exposed to bloodborne pathogens.

For human bites, the clinical evaluation must include the possibility that both the person bitten and the person who inflicted the bite were exposed to bloodborne pathogens.

Exposure to urine, feces, vomitus, or sputum is considered a potential bloodborne pathogen exposure even if the fluid is not visibly contaminated with blood.

Reporting a Bloodborne Exposure

If a bloodborne exposure has occurred, cleanse the exposed area and report the exposure. Your employer is required to provide an appropriate post exposure management referral at no cost to you. Post exposure treatment should begin as soon as possible.

Your employer must provide the following information to the healthcare professional completing the exposure evaluation:

- Description of the exposed employee’s job.

- Job or procedure the employee was performing when exposed.

- Documentation of the routes of exposure and circumstances under which exposure occurred.

- Results of the source person's blood testing, if available.

- Medical records, including vaccination status relevant to the employee.

Post Exposure Prophylaxis

Post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) provides anti-HIV medications to someone who has had a substantial exposure, usually to blood. PEP has been the standard of care for occupationally exposed healthcare workers since 1996. PEP should be started as soon as possible (within 72 hours), even while awaiting test results from the source person. The PEP medication regime should be continued for 28 days (4 weeks).

PEP for HIV does not provide protection from other bloodborne diseases like HBV or HCV. Hepatitis B post exposure prophylaxis involves administration of hepatitis B immune globulin and an HBV vaccine. The HBV vaccine provides 90% protection from HBV. PEP should occur as soon as possible and no later than 7 days post exposure.

No PEP has been demonstrated to be effective against HCV. The benefit of the use of antiviral agents to prevent HCV infection is unknown and antivirals are not currently FDA-approved for prophylaxis.

The national bloodborne pathogen hotline provides 24-hour consultation for healthcare workers who have been exposed on the job. Call 888-448-4911 for the latest information on prophylaxis for HIV, hepatitis, and other pathogens.