*This course has been retired. There is no replacement course at this time. Please click here to view the current ATrain course listings.

The foundation for treating all forms of CAD is the basic treatment plan for stable angina. This plan begins with therapeutic lifestyle changes, adds medications when necessary, and considers using reperfusion therapy for more serious levels of disease.

Initial Management of Acute Angina

Patients with acute chest discomfort that does not respond to rest or to nitroglycerin or that lasts more than 20 minutes should immediately be taken to an emergency department, preferably by ambulance (Antman et al., 2007).

In choosing among these treatment paths, clinicians rely on the history, physical examination, ECG, and blood tests for cardiac biomarkers. If the discomfort appears to be acute angina, physicians will stabilize the patient and send them along 1 of 4 treatment paths. These paths lead to:

- Immediate treatment: those with ST elevation on initial ECG (percutaneous coronary intervention or IV thrombolytic drugs)

- Admission to a coronary intensive care unit, a telemetry unit, or an observation unit: those without ST elevation but at high risk

- Collection of further data for those who have symptoms that warrant evaluation (stress testing or radionuclide imaging) in the ED

- Discharge home with followup by primary care physician for those who have an obvious non-cardiac cause for their symptoms (Kontos et al., 2010)

Patients most likely to benefit from immediate treatment are those with a major acute myocardial infarction, which can usually be identified by biochemical evidence of heart muscle necrosis (increased blood levels of cardiac biomarkers) and elevations of the ST segments of the ECG waveform.

Patients who should be admitted to coronary units are those most likely to continue developing acute problems over the next 72 hours. These are patients with any of these conditions:

- Recently changing or accelerating angina

- History of myocardial infarction

- Evidence of heart failure

- ECG signs of ischemic changes

- Elevated cardiac biomarkers

- Over 70 years of age

In addition, patients are admitted if there are serious contributing conditions, such as uncontrolled hypertension, hypotension, new cardiodynamic problems, mitral regurgitation, or lung disease (Lee, 2008).

Patients being worked up for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) must first be stabilized. Antithrombotic therapy should then be started and ischemic pain eliminated. Aspirin at 162 to 325 mg should be given (300–600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel for those allergic to aspirin), and chest pain should be treated with sublingual nitroglycerin. For continued chest pain, morphine or fentanyl can be used if blood pressure tolerates nitrates. Intravenous nitroglycerin can be used when other medications have failed to alleviate chest pain (Coven, 2013).

Medical personnel have traditionally been taught the mnemonic MONA (morphine, oxygen, nitroglycerin, aspirin) to remind them of the initial treatment of any suspected ACS patient. However, according to current American Heart Association guidelines, “there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of oxygen in uncomplicated ACS.” If the patient is short of breath, hypoxemic, or has obvious signs of heart failure, oxygen should be titrated to saturation levels ≥94% (AHA, 2015).

The concern is oxygen toxicity and vasoconstriction. Oxygen causes constriction of the coronary, cerebral, renal, and other key vasculatures. If perfusion decreases with blood hyperoxygenation, the administration of oxygen may place tissues at increased risk of hypoxia. Hyperoxia reduces coronary blood flow by 8% to 29% in normal individuals and in patients with coronary artery disease or chronic heart failure. The reduction in coronary artery flow is associated with a reduction in myocardial-tissue oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption (Iscoe et al., 2011).

Test Your Knowledge

When people call to ask advice about the sudden occurrence of chest discomfort:

- Advise them to be taken immediately to the hospital, preferably by ambulance.

- Check to see whether they suffer from panic attacks, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), or peptic ulcer disease (PUD) before advising them.

- Tell them to call their physician immediately.

- Do a quick telephone triage of symptoms to determine the likelihood of an MI.

For patients who are having a suspected myocardial infarction, chewing 2 to 4 tablets of 81 mg aspirin is:

- Not recommended if the patient is a candidate for IV fibrinolytic therapy.

- Not recommended if the patient is already taking daily aspirin.

- No longer recommended for most patients.

- Recommended for all patients unless the patient is allergic to aspirin.

The use of supplemental oxygen:

- Is never recommended for patients with suspected ACS.

- Is only used during cardiac arrest.

- Is recommended only when a patient is short of breath, hypoxemic, or has signs of heart failure.

- Should be titrated to keep oxygen saturation at 100%.

Patients with stable angina who get chest discomfort with exercise:

- Must resign themselves to living with lower levels of exercise or risk having an MI.

- Can safely ignore chest discomfort because their disease is stable.

- Can increase their exercise tolerance with a medically supervised cardiac rehabilitation program.

- Should be put on bed rest to avoid sudden cardiac death.

Answer: A,D,C,C

Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes

With commitment and perseverance, a person can significantly reduce the threats posed by CAD.

Following a peak incidence around 1968, death from CAD declined significantly in the United States. It is estimated that 47% of the decrease in mortality from coronary heart disease in the United States between 1980 and 2000 was attributed to advances in medical therapies, including treatment of acute coronary syndromes and heart failure. Approximately 44% of the reduction was secondary to a decline in cardiovascular risk factors, including hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, smoking, and physical inactivity (Chiha et al., 2012).

Unfortunately, this reduction in the death rate from CAD was partly offset by increases in diabetes and body mass index (BMI). Unfortunately, the cardiovascular disease epidemic continues to evolve rapidly on a global level and is currently responsible for twice as many deaths in developing countries as in developed countries. In low- and middle-income countries, cardiovascular risk factors, especially smoking and obesity, continue to increase in incidence and affect a larger proportion of younger patients. Cardiovascular mortality has been reported 1.5 to 2 times higher among the working population in India, South Africa, and Brazil compared to the United States (Chiha et al., 2012).

Therapeutic lifestyle changes have been scientifically demonstrated to be good treatments for heart disease—namely, stop smoking, eat a diet low in saturated fat and higher in fruits and vegetables, exercise daily, and lose weight. It is the job of the healthcare team to work with the patient to personalize these familiar recommendations. Healthcare providers must offer practical advice that the patient can reasonably follow and that the patient believes is worth following.

In as many as three-quarters of all CAD patients, supervised lifestyle change programs can reduce the amount and severity of angina within three months. During that time, patients can increase their exercise capacity and improve their quality of life. Comprehensive lifestyle change programs can also reduce the chance that patients will require a coronary reperfusion procedure (Frattaroli et al., 2008).

Therapeutic lifestyle changes can prevent coronary artery disease and reduce its severity. Young people, who are increasingly at risk for developing CAD, should be encouraged to follow the same principles of no smoking, low-fat/high-fiber meals, and plenty of physical activity (Libby, 2008).

Smoking Cessation

Therapeutic lifestyle changes begin with smoking cessation. Carbon monoxide and other poisons in cigarette smoke damage many types of cells in the body. Carbon monoxide also reduces blood oxygenation, stressing the oxygen-hungry heart. This stress is compounded by the nicotine in cigarette smoke. Nicotine constricts blood vessels and causes the heart to work harder, raising heart rate and blood pressure, two effects that increase the heart’s workload (Mitchell & Schoen, 2009).

Cigarette smoking accelerates coronary atherosclerosis in both sexes and at all ages and increases the risk of thrombosis, plaque instability, MI, and death. In addition, by increasing myocardial oxygen needs and reducing oxygen supply, it aggravates angina (Antman et al., 2008).

People who stop smoking reduce their risk of death from CAD; however, many people find it difficult to stop smoking. Clinicians can begin by telling patients that continued smoking increases their risk of serious heart problems and death, while quitting reduces this risk. They should then ask patients who smoke if they have thought about quitting. Whatever the answer, clinicians should follow with the offer “When you would like to stop smoking, I’ll be happy to help set up an effective program for you.” For more information, see Cardiac Rehabilitation below.

Low-Fat/High-Fiber Diet

The American Dietetic Association has collected evidence demonstrating that a low-fat diet with 12 to 33 g per day of fiber from whole foods or up to 42.5 g per day from supplements can help to reduce blood pressure, correct dyslipidemia, reduce indicators of chronic inflammation, and reduce weight (Am. Diet. Assoc., 2008). A low-fat/high-fiber diet has also been shown to reduce the risk of developing CAD.

In one large study of older adults, eating whole-grain fiber in the equivalent of an extra 2 slices of whole-grain bread per day reduced the number of:

- Deaths from CAD by 13%

- Nonfatal myocardial infarctions by 6%

- Ischemic strokes by 24%

Compared with medical or surgical interventions, nutritional changes are relatively low-risk, low-cost, and widely available. Therefore, the practical importance of even a small change in risk may be significant on a population or public health level (Mozaffarian et al., 2003).

Recommended Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes

Source: NHLBI, 2006.

- Less than 7 percent of daily calories should come from saturated fat. This kind of fat is found in some meats, dairy products, chocolate, baked goods, and deep-fried and processed foods.

- No more than 25 to 35 percent of daily calories should come from all fats, including saturated, trans, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats.

- Cholesterol intake should be less than 200 mg a day.

- Foods high in soluble fiber help prevent the digestive tract from absorbing cholesterol. These foods include:

- Whole-grain cereals such as oatmeal and oat bran

- Fruits such as apples, bananas, oranges, pears, and prunes

- Legumes such as kidney beans, lentils, chick peas, black-eyed peas, and lima beans

- Choose a diet rich in fruits and vegetables to decrease cholesterol. These compounds, called plant stanols or sterols, work like soluble fiber.

- Fish such as salmon, tuna (canned or fresh), and mackerel are a good source of omega-3 fatty acids and should be eaten twice a week.

- Limit sodium intake. Choose low-salt and “no added salt” foods and seasonings.

- Limit alcohol intake. Too much alcohol raises blood pressure, triglyceride level and adds extra calories.

- Men should have no more than two drinks containing alcohol a day.

- Women should have no more than one drink containing alcohol a day.

Increased Physical Activity

Regular exercise helps to correct dyslipidemia. It also reduces insulin resistance, decreases platelet aggregation, aids weight loss, improves sleep, and gives people a sense of well-being. For low-risk patients who get no cardiac symptoms with exercise, the minimum amount of recommended activity is 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity such as brisk walking, on at least three different days each week.

A recommended goal is for everyone to include 30 to 60 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity in their schedule every day in addition to their daily activities such as gardening or housework (Fraker et al., 2007).

To have a significant effect, regular activity must become a continuing part of a patient’s life. Patients stick to exercise goals more consistently when the activities are undertaken in a structured, supervised program—for example, when the patients attend regular classes or when they keep a record and report regularly to someone.

Exercise programs may have to be introduced gradually. At first, patients with stable angina may be limited by the occurrence of angina and will probably need to adapt even their normal activities. The appearance of angina or anginal equivalents indicates that an activity is too strenuous, so patients should revise their normal activities to avoid the angina.

In many cases, patients can reduce the heart’s workload and prevent angina simply by doing stressful activities at a slower pace. Patients should be warned that their exercise tolerance should be customized to their comfort and daily activities. Angina occurs more frequently in the morning, after meals, and in cold weather.

After finding an angina-free daily routine, most patients should then aim to increase their exercise tolerance. Regular exercise, beyond their daily activities, is beneficial for almost all patients with CAD. For symptomatic and high-risk patients, a medically supervised cardiac rehabilitation program is recommended. The goal for most patients is to progress to a minimum of 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity on at least five different days each week (Antman et al., 2007). See Cardiac Rehabilitation below for more details.

Weight Loss

During the past twenty years there has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States, and rates remain high. Thirty-five percent of U.S. adults and approximately seventeen percent (12.5 million) of children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years are obese. Obesity-related conditions include heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer—some of the leading causes of preventable death (CDC, 2012c).

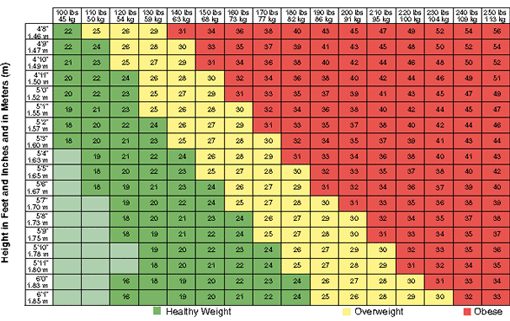

BMI Chart

Source: Courtesy of webmd.com.

Excess body weight makes the heart work harder, and excess fat fosters atherosclerosis. A person is considered overweight if their body mass index (BMI, see chart below) is 25 to 29.9 kg/m2, while obesity is defined to be BMI >30 kg/m2.

Calculating BMI is one of the best methods for population assessment of overweight and obesity. Because calculation requires only height and weight, it is inexpensive and easy to use for clinicians and for the general public. The use of BMI allows people to compare their own weight status to that of the general population. The standard weight status categories associated with BMI ranges for adults are shown in the following table (CDC, 2011).

Body Mass Index (BMI): Weight in Pounds (lbs) and Kilograms (kg)

BMI values for selected heights between 4'10" and 6'3" and for selected weights between 100 lbs and 248 lbs. BMI values are kilograms of body weight per square meter of body surface area (kg/m2) (NHLBI, n.d.).

Excess body weight is a CAD risk factor. A person need not be obese to suffer a higher risk of CAD: overweight people with a BMI >26.5 have an increased likelihood of developing atherosclerosis, and overweight people with a BMI >27.5 have an increased rate of death from CAD (Lewis et al., 2009).

When a person’s excess fat is visceral (ie, inside the abdomen as opposed to directly under the skin), the effect on atherosclerosis is worse. A quick and effective measure of intra-abdominal fat is a person’s waist circumference. Waist circumferences >102 cm (40 in) in men and >89 cm (35 in) in women represent increased coronary artery risks.

Weight management is a key part of the therapeutic lifestyle changes recommended for people with CAD. Patients should be encouraged to maintain a BMI <25 kg/m2. Men should aim for a waist circumference <102 cm (40 in), while women should aim for a waist circumference <89 cm (35 in) (Antman et al., 2007; Fraker et al., 2007). To measure waist size correctly, one should stand and place a tape measure around the middle, just above the hipbones and measure the waist just after breathing out.

Both low-carbohydrate diets (<130 g carbohydrates/day) and low-fat diets seem to be equally effective. The most effective way to lose weight and to maintain the lower weight is participation in a comprehensive weight-loss program that combines low-calorie diets, behavior modification, and regular exercise. Healthy weight loss must include a lifestyle of long-term changes in daily eating and exercise habits.

Evidence shows that people who lose weight gradually and steadily (about 1 to 2 pounds per week) are more successful at keeping weight off. In order to lose weight, a person must reduce the daily caloric intake and use up more calories than are taken in. Since 1 pound equals 3,500 calories, caloric intake must be reduced by 500 to 1000 calories per day to lose about 1 to 2 pounds per week (CDC, 2016b).

Even a modest weight loss, say, 5% to 10% of total body weight, is likely to produce health benefits, such as improvements in blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and blood sugars. Long-term success is achieved through healthy eating, and physical activity most days of the week (about 60–90 minutes, moderate intensity) (CDC, 2016b).

Stress Management

It is generally believed that psychological stress worsens CAD. In one small study, an intensive stress management program was shown to actually reduce the amount of stenosis in coronary arteries (Pischke et al., 2008). Anger, frustration, fear, anxiety, depression, and insomnia are thought to foster an internal biochemistry conducive to atherosclerosis and perhaps to acute coronary syndromes. Physicians therefore advise CAD patients to lessen as possible the stressors in their lives and to learn and use simple relaxation techniques (Davis, 2008). A CAD patient struggling with any form of psychological stress should be offered a referral to a mental health professional.

Medications

Medications are used to manage all forms of CAD:

- Stable angina. Drugs that dilate arteries, slow heart rate, and lower blood pressure can temper the cardiovascular effects of stressful activities. Drugs in this category include nitrates, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers.

- Acute coronary syndromes. Antiplatelet drugs can be taken daily to reduce the size and prevalence of thrombotic clots. Drugs in this category include aspirin and clopidogrel.

Nitrates

Nitrates are drugs that release nitric oxide (NO) when metabolized. Nitric oxide relaxes arterial walls, causing the blood vessels to dilate, and the dilation of coronary arteries will ease ischemic heart pain.

Sublingual nitroglycerin tablets are the most effective of the nitrates. These tablets will relieve angina within 5 minutes. Nitroglycerin tablets can also be taken 5 minutes before exercise or other stresses to prevent angina. The most common side effects of nitroglycerin are headache, dizziness, and a pulsing feeling in the head. Longer-acting nitrates can also be effective; however, responses vary, and the appropriate drug and dosage must be discovered empirically for each patient.

Patients with stable angina often get relief from an episode of angina by resting. If a few minutes of rest are not sufficient, sublingual nitroglycerin tablets will usually relieve the angina. As many as three tablets can be taken at 3- to 5-minute intervals.

When rest and nitroglycerin do not work within a few minutes, the individual may be having an acute coronary syndrome. In these circumstances, the person should be taken immediately by ambulance to an emergency department (Antman et al., 2008).

Patients should keep a diary, recording episodes of angina and the responses to rest and to nitroglycerin. This diary can help physicians to recognize when stable angina is becoming unstable.

Nitroglycerin tablets deteriorate. They last for 3 to 5 months when tightly capped and stored in a refrigerator. When kept in a pill container and carried by a patient, the tablets deteriorate more rapidly.

Nitrates Prescribed for Angina

Short-term (lasting 2 to 10 minutes)

- nitroglycerin (sublingual tablets, sublingual spray)

- isosorbide dinitrate (sublingual spray)

Intermediate-term (lasting ~1 hour)

- isosorbide dinitrate (sublingual tablets)

Long-term (lasting >2 hours)

- nitroglycerin (ointment, transdermal patch, oral sustained release, IV)

- isosorbide dinitrate (oral pills, chewable tablets, oral slow release, IV)

- isosorbide mononitrate (oral pills)

Beta-Adrenergic Blockers

Exercise and other stressors raise both heart rate and blood pressure via the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic neurotransmitters are adrenergic chemicals such as epinephrine and norepinephrine. Adrenergic blocking drugs will reduce the ability of the sympathetic nervous system to stimulate end organs, such as the heart and the smooth muscles in arteries.

Sympathetic stimulation has different effects on different tissues, and it has been possible to find drugs that selectively block specific sympathetic effects. Beta-adrenergic blockers (beta blockers) are especially effective at limiting the cardiovascular effects of sympathetic stimulation. Beta blockers inhibit the increases in heart rate and blood pressure that are normally caused by exercise and stress, while having little effect on the heart at rest (Antman et al., 2007).

To reduce angina and to lower the risk of an MI, many CAD patients take long-acting or sustained-release beta blockers once daily. Beta blockers are also prescribed as protection after an acute coronary syndrome (Alaeddini, 2012).

Side effects can require a beta blocker to be taken at a lower dose or to be discontinued entirely. When being discontinued, beta blockers should be tapered and not stopped suddenly. The possible side effects of beta blockers include fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, nightmares, impotence, cold hands and feet, intermittent claudication, bradycardia, impaired atrioventricular conduction, left ventricular failure, bronchial asthma, and, in diabetics, an intensification of the hypoglycemia produced by oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin. Beta blockers are usually not given to patients with asthma or other types of reversible airway obstruction, severe bradycardia, atrioventricular conduction disturbances, Raynaud’s phenomenon, or a history of clinical depression (Antman et al., 2008).

Beta Blockers Prescribed for Angina

Selective beta 1 blockers

- Acebutolol

- Atenolol

- Betaxolol

- Bisoprolol

- Esmolol (an IV drug)

- Metoprolol

Nonselective beta blockers

- Carteolol

- Carvedilol

- Labetalol

- Nadolol

- Penbutolol

- Pindolol

- Propranolol

- Sotalol

- Timolol

Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium channel blockers dilate coronary arteries, lower blood pressure, and reduce the heart’s oxygen requirements. However, calcium channel blockers can produce hypotension, edema, and bradycardia and can worsen heart failure.

Overall, the effects of calcium channel blockers are similar to the effects of beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers are often prescribed when beta blockers cannot be used, such as with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or when the side effects of beta blockers such as depression, sexual disturbances, or fatigue pose too much of a problem.

Diltiazem and the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers can be combined with beta blockers and nitrates, although the specific doses must be customized for each patient.

In 2006 the FDA approved the use of a metabolic modulator, ranolazine (Ranexa), a new anti-anginal medicine, for treatment of refractory angina. Ranolazine is a sodium current inhibitor that, unlike other anti-anginal drugs, has no effect on heart rate or blood pressure. It is given in twice-daily oral doses of 500 to 1000 mg, and is usually prescribed in combination with another anti-anginal drug such as a nitrate, a beta blocker, or amlodipine (Antman et al., 2008). Ranolazine is used to relieve or prevent chronic angina in patients with moderately severe symptoms (O’Rourke et al., 2008).

Ranolazine has recently been shown “to reduce angina frequency and sublingual nitroglycerin use in patients with type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, and chronic angina,” according to results of a study presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 62nd Annual Scientific Session (Hughs, 2013).

Calcium Channel Blockers Prescribed for Angina

Dihydropyridines

- Amlodipine

- Felodipine

- Isradipine

- Nifedipine, slow release

Other calcium channel blockers

- Diltiazem, slow release

- Verapamil, slow release

Antiplatelet Drugs

Blood clots and an activated clotting pathway are major causes of acute coronary syndromes. Aspirin and clopidogrel (Plavix), two drugs that inhibit platelet aggregation, have been shown to reduce a person’s risk of having an acute coronary syndrome.

Aspirin

Aspirin is the most widely used and tested antiplatelet drug in CAD, and it is the cornerstone of antiplatelet therapy in treatment and prevention of CAD. In acute coronary syndrome and thrombotic stroke, acute use of aspirin can decrease mortality and recurrence of cardiovascular events. As secondary prevention, aspirin is believed to be effective in acute coronary syndrome, stable angina, revascularization, stroke, and atrial fibrillation (Dai & Ge, 2012).

For ACS patients, the current American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines recommend that aspirin should be administered as soon as possible, with an initial loading dose of 162 to 325 mg and continued indefinitely with a dose of 75 to 162 mg daily. The use of aspirin (162 mg chewed, to ensure rapid therapeutic blood levels) was associated with a 23% reduction of vascular mortality rate in MI patients and close to a 50% reduction of nonfatal re-infarction or stroke, with benefits seen in both men and women. In unstable angina and NSTEMI patients, aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk of fatal or nonfatal MI by 50% to 70% during the acute phase and by 50% to 60% at 3 months to 3 years (Dai & Ge, 2012).

The highest benefit of aspirin was seen in those undergoing coronary angioplasty, with a 53% reduction in MI, stroke, or vascular deaths. In percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the use of aspirin significantly reduces abrupt closure after balloon angioplasty and significantly reduces stent thrombosis rates (Dai & Ge, 2012).

Long-term aspirin therapy reduces the yearly risk of serious vascular events (nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or vascular death), which corresponds to an absolute reduction of nonfatal events and to a smaller reduction in vascular death. Although the long-term use of aspirin has been associated with gastrointestinal and other bleeds, the benefits outweigh the risks. For secondary prevention, aspirin is recommended in conjunction with lifestyle changes and smoking cessation to reduce an individual’s overall risk of further cardiovascular events (Dai & Ge, 2012).

Clopidogrel (Plavix)

Clopidogrel, also known as Plavix, is an antiplatelet drug used for peripheral vascular disease, ACS, recent MI, or stroke. Clopidogrel is given as an initial 300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily (Mechcatie, 2012). Aspirin and clopidogrel can be combined, however caution should be taken regarding an increase risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Influenza Vaccination

Patients who have CAD should get a seasonal flu shot every year. Those over age 65 should also consider a pneumonia vaccine.

Treating Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of metabolic risk factors defined by the International Diabetes Federation as central obesity (measured by waist circumference) plus any two of the following four risk factors (Edwardson et al., 2012):

- Elevated blood pressure (systolic 130 or above or diastolic 85 or above)

- Triglycerides above 150 mg/dl

- Reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

- Elevated fasting blood sugar (greater than 100 mg/dl)

Research has shown that individuals with metabolic syndrome are at an increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular events, and mortality from CAD. Approximately one-quarter of European, American, and Canadian adults have metabolic syndrome. The high prevalence of the syndrome and the associated health consequences demonstrate the importance of understanding the causes of metabolic syndrome in order to implement prevention strategies (Edwardson et al., 2012).

Having just one of the metabolic risk factors does not meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome. However, any of these conditions increases the risk of serious disease. If more than one of these conditions occur in combination, the risk of serious disease is even greater (Mayo Clinic, 2016). Each of these cardiometabolic disorders promotes the development of the others. For example:

- Insulin resistance can lead to dyslipidemia and hypertension.

- Hypertension increases the likelihood of developing diabetes.

- Central obesity can lead to insulin resistance.

People tend to have more than one of these disorders at a time (Buse et al., 2008). Aggressive lifestyle changes can delay or even prevent the development of serious health problems. Treatment of metabolic syndrome involves the separate treatment of each of its components.

In addition to metabolic syndrome, certain other medical conditions are especially problematic for people with CAD. These conditions include:

- Aortic valve disease

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Hyperthyroidism

- Pulmonary disease

- Anemia

Controlling these problems can sometimes reduce or eliminate the angina of concurrent CAD (Antman et al., 2008).

Diabetes

Diabetes and CAD are a deadly combination. Diabetes accelerates coronary atherosclerosis and increases the risk of angina, myocardial infarction, and sudden coronary death. Yet, according to Libby (2008), “most patients with diabetes mellitus die of atherosclerosis and its complications.”

Diabetics are at least 4 to 6 times as likely as nondiabetics to have heart disease and tend to develop heart disease at an earlier age than nondiabetics. Women who have not gone through menopause usually have less risk of heart disease than men of the same age. But women of all ages who have diabetes have an increased risk of heart disease because diabetes cancels out the protective effects of being a woman in her childbearing years (NDIC, 2012).

People with diabetes who have already had one heart attack run an even greater risk of having a second one. In addition, heart attacks in diabetics are more serious and more likely to result in death (NDIC, 2012).

It has been shown that maintaining strict control of blood glucose levels reduces the coronary artery risk posed by diabetes and taking metformin, controlling blood lipid levels (with statins), reducing hypertension, and instituting therapeutic lifestyle changes all lessen the serious complications of CAD in diabetics (Amer. Diet. Assoc., 2016; Fraker et al., 2007; Brunzell, 2008; Libby, 2008).

Dyslipidemia

Lipid disorders underlie atherosclerosis, and treating lipid abnormalities is critical to slowing the progression of CAD. The therapeutic lifestyle changes described above such as stop smoking, eat a low-fat, high-fiber diet, exercise more, and lose weight are the first steps in avoiding or reversing lipid abnormalities. When target blood lipid levels cannot be achieved via lifestyle changes, the next step is the addition of medications, namely statins (Libby, 2008). Low-fat diet means saturated fats are <7% of daily calories, minimal trans fats, and dietary cholesterol <200 mg/day.

Target Blood Lipid Levels for Patients with CAD

LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dl or <70 for those with metabolic syndrome

HDL cholesterol >40 mg/dl for men, >50 mg/dl for women

Triglycerides <150 mg/dl

Source: NDIC, 2016.

To manage CAD, the primary lipid goal is a reduction of LDL cholesterol levels. In the general adult population, the target LDL level is <100 mg/dl. However, for people with CAD, the target LDL level is <70 mg/dl. The recommended type of medication for lowering LDL cholesterol is a statin. Statins can reduce LDL cholesterol by 25% to 50%; they can also raise HDL cholesterol by 5% to 9% and lower triglycerides by 5% to 30% (Brunzell et al., 2008).

Hypertension

High blood pressure (hypertension) worsens atherosclerosis and increases the risks of acute coronary syndrome. High blood pressure was a primary or contributing cause of death for 348,000 Americans in 2008, or nearly 1,000 deaths per day. Of the 68 million American adults who have high blood pressure, 36 million do not have it under control (CDC, 2016c).

About 30% of American adults have prehypertension—blood pressure measurements that are higher than normal, but not yet in the high blood pressure range. Better hypertension management leads to improved health outcomes. A large systematic review of 147 trial reports on the management of hypertension has shown that a reduction of 10 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure and 5 mm Hg in diastolic was associated with a 20% reduction of coronary heart disease and 32% reduction in stroke in one year (Al-Ansary et al., 2013).

Normal, At-Risk, and High Blood Pressure Levels

Source: CDC, 2016c.

Normal

Systolic: less than 120 mmHg

Diastolic: less than 80 mmHg

At Risk (Prehypertension)

Systolic: 120–139 mmHg

Diastolic: 80–89 mmHg

At Risk

Systolic: 140 mmHg or higher

Diastolic: 90 mmHg or higher

* * *

As with all health problems related to CAD, treatment of hypertension begins with therapeutic lifestyle changes. If lifestyle changes are not sufficient, medications should be added (Rosendorff et al., 2007).

Drugs prescribed for hypertension in patients with CAD include:

- Beta blockers. Beta blockers are the first-line antihypertensive drugs for patients with CAD. If necessary, certain calcium channel blockers can be added to or substituted for beta blockers.

- ACE inhibitors. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are antihypertensive drugs and are part of the standard drug therapy for CAD patients who have diabetes or left ventricular dysfunction, even when the patients do not have hypertension. Angiotensin receptor blockers can often be substituted for ACE inhibitors.

- Thiazide diuretics. Thiazide diuretics can be effectively added to other antihypertensive medicines when needed but caution must be taken to maintain serum potassium levels within the normal range.

Reperfusion Therapies

After therapeutic lifestyle interventions are in place, drugs are added to the treatment regimen to control both angina and hypertension. When these medicines still do not reduce the anginal episodes, the next level of treatment is reperfusion therapy (also called revascularization or recanalization therapy).

There are two types of reperfusion procedures: percutaneous interventions to open blocked coronary arteries via a catheter, and surgical artery or vein grafts to bypass obstructed segments of coronary arteries.

In some situations, physicians recommend reperfusion therapy even before learning how well the prescribed drugs will succeed in controlling a patient’s angina. For example, in addition to lifestyle changes and medications, reperfusion is often recommended for patients with any of these conditions:

- >50% stenosis of the left main coronary artery

- Significant stenosis of three major coronary artery branches

- Stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery and one additional major coronary artery branch

Percutaneous Interventions

Percutaneous interventions (PCIs) are accomplished by threading a balloon-tipped catheter into the stenotic segment of an artery. The balloon is inflated until it flattens the offending plaque against the arterial wall and reopens the arterial lumen. In the larger branches of the coronary arteries, the cleared lumen is held open by a metal stent that is left in place permanently.

Obstructed arteries that have been dilated by percutaneous intervention are susceptible to restenosis, so patients are given antiplatelet therapy after the procedure. Currently, by using stents coated with antithrombotic chemicals (drug-eluting stents), the restenosis rates have been reduced to about 10% over six months. When the reopened arteries eventually become blocked again, percutaneous intervention is repeated.

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) uses a grafted blood vessel to deliver blood around the obstructed segment of a coronary artery. Often, the new blood conduit is a length of saphenous vein that has been removed from the patient’s leg. Arteries make better conduits than veins, and an arterial graft can be made by detaching the distal end of the internal thoracic artery (also called the internal mammary artery) and re-attaching it to the stenotic coronary artery beyond the obstructed region; this reroutes blood from the subclavian artery into the coronary circulation.

Bypass grafts are preferred over percutaneous interventions for the simultaneous revascularization of three or more obstructed coronary arteries. Bypass grafts are also preferred when other heart repairs, such as a valve replacement, are needed by the patient.

Test Your Knowledge

Coronary artery bypass grafts (CABG):

- Are always the therapy of choice in a hospital with capacity to perform them.

- Typically use nonhuman materials, such as Teflon tubes or porcine arteries.

- Are the therapy of choice when multiple vessels are blocked and additional heart repairs need to be made.

- Are no longer recommended because studies show that other interventions lead to better survival rates.

Answer: C

The long-term survival advantage after CABG, cited above, was consistent across multiple subgroups based on gender, age, race, diabetes, body mass index, prior heart attack history, number of blocked coronary vessels, and other characteristics. For example, the insulin-dependent diabetes subgroup that received CABG had a 28% increased chance of survival after four years compared with the PCI group (NIH, 2016a).

According to an international study supported by the NHLBI, adults with diabetes and multi-vessel coronary heart disease who underwent cardiac bypass surgery had better overall heart-related outcomes than those who underwent PCI. The study compared the effectiveness of CABG and PCI that included insertion of drug-eluting stents. After five years, the CABG group had fewer adverse events and better survival rates than the PCI group. The survival advantage of CABG over PCI was consistent regardless of race, gender, number of blocked vessels, or disease severity (NHLBI, 2016g).

Test Your Knowledge

New studies that compare CABG and PCI in diabetics with multi-vessel CAD:

- Found fewer adverse events and better survival rates after 5 years for those who underwent CABG.

- Found fewer adverse events for those who underwent PCI.

- Found no difference in survival rates and adverse events after 5 years.

- Found neither procedure to be effective for diabetic patients.

Answer: A

Laser Transmyocardial Revascularization

Another technique is available for reducing the exercise-limiting angina suffered by some patients with severe chronic stable angina. Laser transmyocardial revascularization uses a laser to cut thin channels through the heart’s walls. It is thought that the laser treatment stimulates the formation of new blood vessels that can increase local blood flow to heart muscle. It is also thought that the laser may destroy some of the nerves that are causing the angina (Texas Heart Institute, 2012).

Silent Ischemia

Patients often know when they are having an episode of heart ischemia because it causes angina or an anginal equivalent. However, heart ischemia can also be silent. When coronary artery patients are continually monitored by ECG during their daily lives, ischemic episodes can be detected electrically at times when the patients do not feel any symptoms. This is true both for patients who occasionally experience angina in normal life and for CAD patients who have never experienced angina. People can also have silent heart attacks, especially diabetics who have developed autonomic neuropathy. When patients are discovered to have had a silent MI, it is treated in the same way as a symptomatic one.

Test Your Knowledge

When patients with stable CAD have an episode of heart ischemia, they:

- Almost always have angina or an anginal equivalent at the same time.

- May have no symptoms.

- Must always be taken immediately to an emergency department.

- Should expand their coronary arteries by performing warm-up exercises for 5 to 10 minutes.

Answer: A