*This course has been retired. There is no replacement course at this time. Please click here to view the current ATrain course listings.

Chest discomfort is the most telling symptom of CAD. It can take the form of angina or manifest as acute angina in an MI.

Chest Discomfort

Frequently the chief complaint of a person with CAD is chest discomfort. When a patient presents with a nonacute history of chest discomfort, the workup for possible CAD should include blood work for cholesterol, baseline ECG, stress treadmill, statin or aspirin therapy, and lifestyle modification education.

When a patient comes to a medical facility with very recent or ongoing chest discomfort, a rapid triage and assessment should occur. In the emergency department, clinic, or office, the clinician must quickly distinguish those patients who have potentially life-threatening conditions—MIs, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolus, tension pneumothorax—from nonlife-threatening causes of chest pain or discomfort (Lee, 2008). Conditions such as heartburn, swallowing disorders, pancreatic and gallbladder problems, muscle and bone problems, and lung disorders can all cause symptoms similar to those caused by the heart (Mayo Clinic, 2016). For more details, see Medical Management of CAD below.

Classic Angina

The classic symptom of CAD is a form of chest discomfort called angina. The following symptoms are some of the ways that patients describe angina (Schoen & Mitchell, 2009).

Quality: Squeezing Pressure

The nouns commonly used to describe the feeling of angina include constriction, heaviness, pressure, and tightness. The adjectives commonly used include aching, choking, crushing, smothering, and squeezing. Patients typically hold a clenched fist over their chest when describing the feeling of angina.

Location: Substernal

Most commonly, patients say angina is located substernally, ie, inside the center or lower center of the chest. Patients may also locate the feeling in the epigastric region. Some patients describe angina as a deep ache in their teeth, jaw, neck, shoulder, or arm, on either side of the body.

Duration: A Few Minutes

The angina of stable angina is temporary, lasting 2 to 5 minutes and coming in a wave that worsens, reaching a peak and then subsiding. Unstable angina lasts longer, typically 10 to 20 minutes. The angina of MI has a variable duration, often lasting longer than 30 minutes.

Triggers: Exercise

Angina can be triggered by exercise, sexual activity, exposure to cold weather, emotional stress (anger, fright, frustration), or a large meal. Any physical or emotional stress that causes tachycardia can induce angina.

The angina of acute coronary syndromes (unstable angina or an MI) can be precipitated by exercise, but it can also occur at rest or it can wake a person from sleep. (Occasionally, the angina of stable angina will also occur at night, especially if the patient has sleep apnea.)

Occurrence: Predictable or Unpredictable

The angina of stable angina comes predictably when the patient engages in a certain level of exercise. The angina of unstable angina arises unpredictably, sometimes at increasing or even decreasing levels of exercise. The angina of an MI happens unpredictably.

Relievers: Rest or Nitroglycerin Tablets

The angina of stable angina resolves in about 5 minutes with rest and sublingual nitroglycerin tablets. The angina of unstable angina is usually not relieved by a brief rest, and if it is lessened by nitroglycerin, the pain typically recurs. The angina of an MI usually does not respond to rest or to nitroglycerin.

Accompanying Symptoms: Variable

The angina of an acute coronary syndrome and angina can be accompanied by a variety of other symptoms, including shortness of breath, lightheadedness, nausea, or sweating (Lee, 2008).

Descriptors Not Often Used: Sharp and Brief

Chest discomfort can be caused by many thoracic disorders so it essential to rule out cardiac issues first as they potentially can be the most lethal. For example, chest pain can manifest with gastrointestinal nausea and gastric ulcers can present as a burning sensation in the chest. Here are some comments not typically offered by patients when describing classic angina:

- Sharp

- Brief

- Worsened by chest movements of breathing

- Changes with the patient’s position

- Reproduced by an examiner tapping or pressing on the chest

- Below the umbilicus or above the jaw

- Prolonged ache deep to the left breast

Anginal Equivalents

Angina is the complaint that usually triggers a workup for CAD. However, not all people with CAD get angina. Even during an MI, some people do not experience significant chest discomfort, which is why some people may be surprised to hear their ECG shows that a previous MI had occurred.

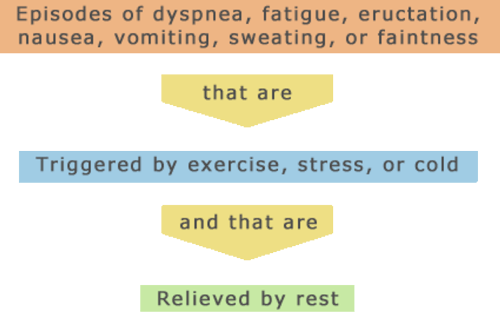

A few complaints other than chest discomfort can also be caused by heart ischemia. Clinicians suspect heart ischemia when patients complain of the following.

When they are caused by heart ischemia, these symptoms behave like angina and are called anginal equivalents. Among patients with CAD, angina is more often reported by men than by women: instead of classic angina, women often report anginal equivalents. Anginal equivalents are also more common for CAD in older adults and in people with diabetes. One of the arts of clinical practice is distinguishing angina—chest discomfort caused by heart ischemia—from other types of chest discomfort.

Test Your Knowledge

The main symptom of CAD is:

- Arrhythmias (usually, atrial fibrillation).

- Chest discomfort called angina.

- Gradually increasing shortness of breath, fatigue, and lower limb edema.

- Sudden inability to get enough air.

An anginal equivalent is:

- A symptom, such as shortness of breath other than chest pain that is caused by heart ischemia, brought on by stress, and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.

- The dose of nitroglycerin that can relieve typical angina in a given patient.

- Sharp chest pain worsened by coughing.

- Angina brought on by emotion not by exercise.

Answer: B,A

A number of medical conditions other than heart ischemia present with acute chest discomfort. These conditions include aortic dissection, aortic stenosis, esophageal reflux, esophageal spasm, gallbladder disease, herpes zoster, musculoskeletal disease or injury, peptic ulcer, pericarditis, pleuritis, pneumonia, psychological/psychiatric problems (eg, panic disorder), spontaneous pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus, and pulmonary hypertension.

Laboratory tests, ECG recordings, and imaging studies may be needed to distinguish these health problems definitively from heart ischemia. However, the patient’s description of chest discomfort can point the clinician toward or away from a diagnosis of heart ischemia. A differential diagnosis for chest discomfort can be determined by evaluating the variations of the following characteristics of pain:

Quality

- Aortic dissection is a tear in the inner wall of the aorta. The pain is severe and sudden.

- Pneumonia, pleuritis, and spontaneous pneumothorax pains are often described as “sharp.”

Location

- Aortic dissection pain typically radiates to the back between the shoulder blades.

- Herpes zoster (shingles) pain follows the pattern of the chest dermatomes.

- Gallbladder and peptic ulcer disease usually produce abdominal as well as epigastric pain.

- Pericarditis pain can radiate to the trapezius muscles.

Duration

- Aortic dissection and spontaneous pneumothorax have a sudden onset of pain that does not stop.

- Gallbladder and peptic ulcer pains can continue for hours.

- Pericarditis pain lasts for hours and sometimes days.

Triggers

- Aortic dissection occurs in a weakened area of the aorta. Chronic hypertension, some inherited conditions such as Marfan syndrome, and trauma to the chest wall are risk factors (Johns Hopkins Medicine, n.d.).

- Musculoskeletal pains are usually caused by injury or trauma.

- Esophageal reflux pain can be brought on by alcohol, aspirin, or lying down after meals.

- Gallbladder and peptic ulcer pains typically appear 1 to 2 hours after a meal.

- Musculoskeletal pain is worsened by movement and can be reproduced by local pressure by the examiner.

- Pericarditis pain is usually aggravated by coughing or by certain postural changes.

- Pneumonia, pleuritis, and spontaneous pneumothorax pains are worsened by the chest movements of breathing and coughing.

Relievers

- Esophageal reflux and peptic ulcer pains can be relieved by antacids.

- Pericarditis pain is sometimes relieved by sitting up.

Accompanying Symptoms

- Aortic dissection can cause loss of peripheral pulses.

- Herpes zoster pain can be accompanied by a vesicular rash in the region.

- Pericarditis pain can be accompanied by a pericardial friction rub.

- Pneumonia, spontaneous pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus, and pulmonary hypertension are typically accompanied by significant dyspnea.

- Pneumonia usually causes cough and fever.

- Pulmonary hypertension can cause edema and jugular venous distension.

- Spontaneous pneumothorax causes decreased breath sounds and respiratory distress. (Lee, 2008)

Medical History

Although the pace and the focus of a workup differ for acute and nonacute angina, much of the collected cardiovascular information is the same. In all cases, the history, physical examination, lab work, imaging, and stress tests will look for evidence of coronary atherosclerosis and of heart ischemia.

Age of Patient

The typical CAD patient is middle-aged or older. Men tend to have their first symptoms when they are older than 50 years. Women tend to have their first symptoms when they are older than 60 years. Symptomatic CAD is much less common in premenopausal women, unless they are smokers or have metabolic syndrome.

Differences in CAD Between Men and Women

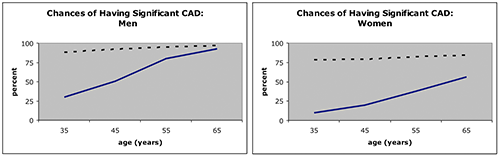

Source: Douglas et al., 2008.

The solid and dashed lines in both of the above graphs represent the percent of people with stable angina who actually have significant CAD. The solid line is for people who have angina but who do not have diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or a history of smoking. The dashed line is for people who have angina and diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and a history of smoking, showing the strong correlation between those conditions and CAD.

Family Medical History

Coronary artery disease is most likely to be found in people with first-degree relatives who have had ischemic heart problems.

Patient’s Lifestyle

Atherosclerosis is associated with smoking, a sedentary lifestyle, and diets that are high in fats and calories.

Physical Findings

Atherosclerosis is a whole-body disease because it affects the circulatory system throughout the body. People with atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries usually have similar problems in other arteries, so they may have such complaints as intermittent claudication, foot pain, cold feet, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), or stroke. Additionally, they may have other health problems that foster atherosclerosis, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, or obesity.

A patient with asymptomatic CAD or with stable angina may have an unremarkable physical examination. Sometimes, however, the patient will have signs of atherosclerosis, such as carotid, femoral, or renal artery bruits, diminished pulses in the legs, ankles, or feet, or visible venous occlusions in the retina. A patient with CAD may also have hypertension and funduscopic signs of hypertensive retinopathy (Antman et al., 2008).

The heart examination, too, may be normal. On the other hand, CAD can produce unrecognized (silent) myocardial infarctions, and the heart examination of a patient with CAD will sometimes uncover signs of previous ischemic damage. For example, there can be murmurs (from weakened papillary muscles), widened split sounds (from damage to the heart’s conduction system), or a diminished first sound (from weakened ventricular contractions).

Long-standing CAD can cause heart failure. A patient with heart failure may have an enlarged heart, lower-extremity edema (swollen legs, ankles, or feet), and distension of the jugular veins. Heart failure can also lead to cyanosis, pulmonary edema, heart murmurs, or heart gallops.

Laboratory Tests: Cardiac Biomarkers

There are no laboratory tests specifically for CAD. The laboratory workup for CAD, instead, is an assessment of risk factors, using blood tests for diabetes, kidney disease, dyslipidemia, and chronic inflammation (C-reactive protein levels and homocysteine) (Antman et al., 2008).

When heart muscle cells die, intracellular proteins leak into the circulation, and some of these proteins can be identified using blood tests. In investigating a potential myocardial infarction, blood is tested for these intracellular heart molecules—cardiac biomarkers—which would be released only by dying heart muscle cells. The appearance of cardiac biomarkers in the bloodstream is a reliable sign of heart muscle death (myocardial necrosis). The tests are repeated 6 to 9 hours later, because the damage caused by heart ischemia can continue for a number of hours. After an MI, blood levels of cardiac biomarkers can remain high for 1 to 2 weeks.

Currently, cardiac troponin T and cardiac troponin I are considered more sensitive indicators than other commonly used biomarkers such as creatinine kinase-MB (CK-MB). Normally, blood levels of cardiac troponins are practically undetectable; therefore, detectable blood levels indicate heart muscle damage. Higher levels of cardiac troponins indicate damage that is more extensive.

While an elevated level of cardiac biomarkers is a trustworthy measure of heart muscle injury, detectable biomarkers do not reveal the cause of the injury. Heart muscle damage is often caused by ischemia, but it can also be caused by infection, inflammation, heart failure, or metabolic disorders. Elevated cardiac biomarkers will accompany trauma (including surgery), myocarditis, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, congestive heart failure, arrhythmias, renal failure, poisoning, and even extreme exertion.

In diagnosing myocardial infarctions, elevated cardiac biomarkers are best used as confirmation of heart muscle damage when there are other indications that heart ischemia may have occurred.

Imaging Studies

A full range of imaging techniques is employed in diagnosis of cardiac disease.

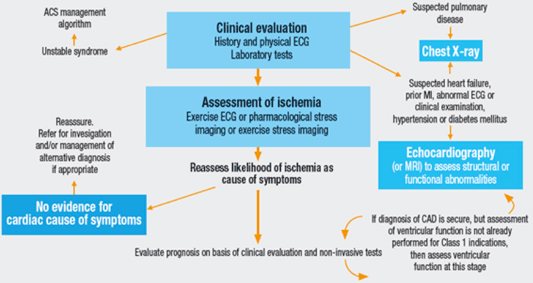

Algorithm for the initial evaluation of patients with clinical symptoms of angina. Source: The CLARIFY Registry: Management of Stable Coronary Artery Disease in Clinical Practice.

Chest X-Ray

In diagnosing CAD, a chest x-ray, which shows heart size, is a priority when considering the possibility of accompanying heart failure.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography, or “echo,” is a painless test that uses sound waves to create pictures of the heart in motion. The pictures show the size and shape of the heart and how well the heart’s chambers and valves are working. Echo also can pinpoint areas of heart muscle that aren’t contracting well because of poor blood flow or injury from a previous heart attack.

A type of echo called Doppler ultrasound shows how well blood flows through the heart’s chambers and valves. Echo can detect blood clots inside the heart, fluid buildup in the pericardium (the sac around the heart), and problems with the aorta (NHLBI, 2016d).

Computed Tomography (CT)

Cardiac computed tomography (CT) uses x-rays to produce a series of images of each part of the heart, then assembles them to make a three-dimensional picture. Sometimes an iodine-based dye is injected into an IV during the scan to further highlight the coronary arteries. This is called coronary CT angiography.

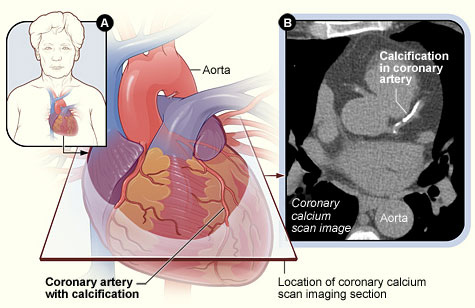

Coronary calcium scans are used to scan the coronary arteries for calcium deposits, which are usually a sign of longstanding atherosclerotic plaque (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Two imaging techniques can show calcium in the coronary arteries: electron-beam computed tomography (EBCT) and multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) (NHLBI, 2012b).

Coronary Calcium Scan Image

(A) The position of the heart in the body and the location and angle of the coronary calcium scan image; (B) scan image showing calcification in a coronary artery. (In the CT scan, the patient’s back is at the bottom of the image, and the patient’s sternum is at the top.) Source: NHLBI, 2016e.

Multi-slice CT is a high-resolution technique that provides good visualization of the structure of the coronary arteries. In many cases, multi-slice CT can allow an accurate diagnosis of CAD, although this is at the expense of subjecting patients to higher than usual doses of radiation (Lee, 2008).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) gives high-resolution images of the coronary arteries without subjecting patients to radiation. When contrast agents are used, MRI images can also show the relative perfusion of various regions of the heart (Antman et al., 2008). Cardiac MRI creates both still and moving pictures of the heart and major blood vessels.

Cardiac Catheterization Angiography

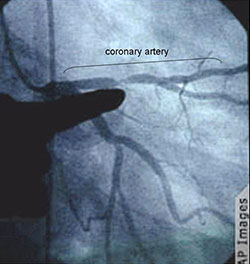

Angiograph of a Stenotic Segment in a Coronary Artery

The finger is pointing to the narrowed region of a dye-filled coronary artery. Source: Gebel, 2008.

Cardiac catheterization angiography (cardiac arteriography) reveals the outlines of the flow space inside the coronary arteries. During this procedure, a catheter is inserted into an artery in the groin or arm and dye is injected into a coronary artery to search for stenotic segments. Guided by x-rays, the catheter can be moved up into the heart; there, in ideal conditions, narrowed (stenotic) arterial segments or blockages can be seen clearly. Angiography cannot detect early atherosclerotic plaque, which builds up inside the arterial wall but does not yet protrude into the arterial lumen. Cardiac angiography is also used to assess the performance of the cardiac valves and the left ventricle.

Cardiac catheterization is an invasive procedure and it brings risks, so it is not done on all patients with diagnosed or suspected CAD. Individuals who qualify for coronary angiography include patients who have:

- STEMI or non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI)

- Chronic stable angina and who are being considered for reperfusion surgery, a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)

- Anginal equivalent

- Patients with a moderate to large area of intact heart and no signs or symptoms or mild symptoms of ischemia

- Patients with moderate to severe ischemia (Antman et al., 2008; Stouffer, 2012)

Test Your Knowledge

When examining patients with suspected CAD, chest x-rays:

- Can give a definitive diagnosis.

- Are not useful.

- Will highlight the ischemic regions of the heart.

- Are used to recognize possible co-existing heart failure.

Cardiac catheter angiography:

- Uses dye injected into a coronary artery to search for stenotic segments.

- Is the definitive diagnostic technique for an MI.

- Has risks and is only used in preparation for coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

- Has risks and cannot be used if a person has ever had an MI.

Online Resource

Cardiac Catheterization—Patient Education Video [7:19]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cUIbLRO2pnU

Answer: C,A

Electrocardiography

All patients with possible heart problems should have a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). In a patient with stable angina, the heart muscles may not be ischemic at rest and a resting ECG can be normal. However, if areas of heart muscle are ischemic, or if past episodes of ischemia have left damaged muscle, there will be characteristic signs on the ECG.

On ECG recordings, ischemia is typically diagnosed from changes in the shape and position of the ST segment of the waveform:

- The vector of the most significant ST changes indicates the region of heart muscle that is suffering ischemia.

- The elevation or depression of the ST segment indicates the portion of the heart wall (subendocardium, epicardium, or the entire thickness, ie, transmural) that is suffering ischemia.

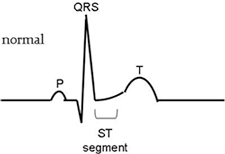

ECG Waveforms

Top: Normal ECG waveform. Bottom: ECG waveform in which the ST segment is raised significantly, indicating an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (ie, a STEMI).

A myocardial infarction with elevated ST segments (a STEMI) suggests epicardial or transmural damage. This type of damage is the most likely to be rescued or reduced by immediate reperfusion therapy (Goldberger, 2008). The most common location of cardiac tissue damage is in the anterior lower leads. The formal definition of a STEMI is at least 2 contiguous leads of >2 mm elevation. Regardless of the type of STEMI, all will be treated the same—by quick coronary revascularization.

During an acute coronary syndrome, the patient’s ECG can change repeatedly; therefore, physicians will take successive ECG recordings to monitor evolving events during the first 48 hours.

Stress Testing

Stress tests increase the oxygen demands of the heart in a controlled setting to search for evidence of activity-dependent ischemia.

ECGs and Echocardiograms with Increased Activity

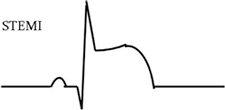

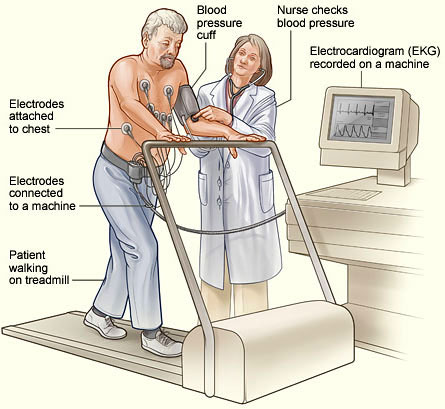

Sometimes patients who report episodes of chest discomfort during exercise have no evidence of heart ischemia on ECGs taken in the office while the patient is resting. To check whether the patient’s exercise-dependent chest discomfort is angina, ECG recordings can be taken while the patient exercises (usually on a treadmill) in a medically monitored environment.

Patient Undergoing Stress Test

An exercise stress test with the patient closely monitored. Source: NHLBI, 2016f.

Echocardiograms, which show heart movements and ventricular wall thicknesses, can also be used in stress tests. Stress echocardiography is a more sensitive test for heart ischemia than is stress ECG testing.

If a patient cannot exercise sufficiently to complete the test, the heart can instead be stressed pharmacologically using drugs such as adenosine, dipyridamole, or dobutamine.

Stress testing should not be done during a potential acute coronary syndrome.

Test Your Knowledge

To document episodes of heart ischemia, stress tests have:

- Actors berate the patient.

- The patient exercise, generally on a treadmill.

- The patient attempt to do two tasks at once.

- The patient eats a large meal followed by coffee and dessert.

Answer: B

Confirming Diagnoses/Identifying Patients at Risk

Stress tests are most helpful when they confirm an uncertain diagnosis of CAD. Negative stress tests are not as helpful, because about 1 out of 4 patients with CAD will show no diagnostic changes during a stress test.

Certain findings in stress tests can identify patients who have a high risk of developing an acute coronary syndrome. Worrisome findings include signs or symptoms of heart ischemia:

- At low levels of exercise

- But no increase in blood pressure with continuing increases in exercise

- That persist >5 minutes after the end of the exercise (Douglas et al., 2008)

Prognosis

From a patient’s medical profile and test results, clinicians can estimate the patient’s risk of suffering an acute coronary syndrome. Tables are available for quantifying this risk, but the first step is to distinguish low and high-risk patients.

Low-Risk Patients

In patients with CAD, the chances of developing an acute coronary syndrome are lowest when:

- A stress test finds no problems, and

- The left ventricle appears to be functioning normally, and

- The coronary arteries look normal in angiograms

High-Risk Patients

Patients with CAD have higher chances of developing an acute coronary syndrome in any of the following situations:

- The patient has significant risk factors for atherosclerotic CAD, including:

- Age >75 years

- Diabetes

- Extreme obesity

- Peripheral or cerebrovascular artery disease

- Dyslipidemia

- History of smoking

- Hypertension

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- The patient has a history of heart problems, including:

- Episodes of unstable angina

- Past myocardial infarctions

- Heart failure or heart failure signs, such as pulmonary edema, a heart gallop, an enlarged heart, mitral regurgitation, or a reduced ejection fraction (<40%)

- The patient has worrisome stress test results, including:

- Inability to exercise >6 minutes

- Ischemic signs or symptoms at low stress levels

- Severe ischemia during testing

- The patient has worrisome cardiac catheterization results, including:

- Increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure or volume

- Reduced ejection fraction

- Stenosis >50% in the left main or the left anterior descending coronary artery

- The patient has extensive coronary artery calcification (Antman et al., 2008)