Penalties against possession of a drug should not be more damaging to an individual than the use of the drug itself—and where they are, they should be changed.

Jimmy Carter

Drug Abuse Message to Congress

August 2, 1977

A world of controversy surrounds the medical use of cannabis. In the United States we have been taught about “marijuana” as a drug of abuse, and cannabis is currently a forbidden medication in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. However, cannabis is an ancient medication with a wide margin of safety and it is useful in an array of medical conditions and ailments. A number of states have passed medical marijuana laws or are considering such laws despite the federal prohibition. Patients are using cannabis as medication, and it is imperative that healthcare professionals understand not only the risks and benefits of this herbal medication but also the legal issues involved in its use.

This course will review the current federal and state laws regarding cannabis and the history of its medicinal use throughout the world. It looks at the chemical components of the cannabis plant in light of the newly discovered cannabinoid system within the human body. It reviews the safety profile of cannabis and considers patient risks, then looks at the indications for use as well as dosage and administration. The course includes a section on patient and family education and concludes by addressing the legal and ethical challenges for healthcare professionals.

In the formal education of today’s healthcare professionals, marijuana has been seen exclusively as a drug of abuse. However, in the early twentieth century cannabis was presented as an effective analgesic and sleep medication in pharmacology classes (Blumgarten, 1919). At the time there were numerous preparations of cannabis and it was considered an essential medication (Aldrich, 1997).

What happened?

First we will correct the common myths and misconceptions regarding marijuana/cannabis. A brief review of its use as an ancient medication will be followed by a historical reference to the reefer-madness era, which marked the beginning of marijuana prohibition and led eventually to its placement in Schedule I of the controlled substances.

Politics and prejudice are now coming head to head with science and compassion as we understand the plant and how it interacts with the human body. Patients are desperate for this medication and the public overwhelmingly supports legal access to it. State and federal laws are in conflict and healthcare professionals are caught in the middle. In this changing climate, it is important that healthcare workers understand the use of cannabis as a medication.

Myth Busters

Marijuana is not medication. False. Cannabis has been used as medication throughout recorded history (Abel, 1980; Aldrich, 1997). It was popular in the United States prior to the reefer-madness campaign that lied about its effects. As of July 2019, 34 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, as well as the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia, have recognized marijuana/cannabis as a medicine.

Marijuana is a dangerous drug. False. Cannabis is “one of the safest therapeutic substances known to man” (Young, 1988). Acute and long-term use of cannabis has very low toxicity (Pertwee, 2014).

Cannabis is highly addictive. False. Compared to most drugs of abuse, cannabis is much less addictive (Hall et al., 1999; Grucza et al., 2016).

Marijuana is a “gateway” drug. False. The illegal status of marijuana exposes the user to the illicit drug trade. Cannabis use does not cause a person to try other, “harder” drugs (Joy et al., 1999).

Marijuana has more than four hundred constituents. True. Fruits, vegetables, and herbal medications contain hundreds of constituents, but that does not make them dangerous for consumption.

Marinol is legal marijuana in pill form. False. Marinol is synthetic tretrahydrocannabinol (THC) and lacks many of the other therapeutic constituents found in cannabis.

Marijuana kills brain cells. False. Cannabis has neuroprotective properties (Izzo et al., 2009, Pertwee, 2014).

Marijuana causes cancer. False. Longitudinal studies show no increase in cancers related to cannabis use (Freimuth et al., 2010; Hashibe et al., 2006). New research on the endocannabinoid system (ECS), as well as animal research, indicates that cannabis can kill cancer cells (Izzo et al., 2009; Velasco, et al., 2012).

Allowing the legal use of medical cannabis will send the message to kids that it is good for you. False. Medication should always be used cautiously. What is therapeutic for one person may be deadly for another. Children need to be taught to respect medications and their proper applications in their lives. Not allowing patients to use this medication sends a distorted message to our youth.

Marijuana causes schizophrenia. False. There is no evidence to show that cannabis causes schizophrenia (Macleod et al., 2006). In populations where there has been an increase in cannabis use, there has been no subsequent increase in the incidence of schizophrenia (Frisher et al., 2009). There does seem to be some consensus that the very high THC strains may precipitate a psychotic experience for some folks and should be taken as a warning sign for them with future use of cannabis (Pertwee, 2014).

Marijuana is more potent today. Partly true. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the primary psychoactive cannabinoid found in cannabis, and many growers have developed strains with higher THC content. However, in its natural form, other cannabinoids found in cannabis—such as cannabidiol (CBD)—serve to dampen the psychoactive effects of THC.

History and Current Status

Cannabis has been used as medication since ancient times. As stated earlier, in the early twentieth century physicians routinely used various cannabis products with their patients. Many of the pharmaceutical companies (eg, Ely Lilly, Parke Davis, Merck) sold various cannabis tinctures, tablets, or topical preparations. By the 1930s, Prohibition had ended and the Director of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, Harry Anslinger, spearheaded a campaign to demonize cannabis. At that time cannabis was being used recreationally by jazz musicians in the South, who called it “reefer,” and by Mexican soldiers, who called it “marijuana.”

Anslinger began spreading stories about “a new drug menace called marijuana” that was causing users to commit violent crimes or go insane (Bonnie & Whitebread, 1974; Abel, 1980). His efforts led to the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which resulted in a prohibitive tax on the medication and ultimately led to its removal from the U.S. Pharmacopoeia by 1941. Since that time, cannabis has no longer been included as a medication in pharmacology texts, and healthcare professionals are taught only that marijuana is a drug of abuse.

In 1970 Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), which created a system to regulate psychoactive drugs (CSA, 1970). Five levels (Schedules I to V) were established to categorize drugs according to their medical utility, abuse potential, and safety of use under medical supervision. Schedule V is the least restrictive category and Schedule I is the forbidden drug category.

To belong in Schedule I, a drug must meet three criteria:

- It has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.

- It is highly addictive.

- It is not safe for medical use.

Schedule I includes marijuana, heroin, LSD, and more.

Schedule II drugs are highly addictive, but have been determined to have medicinal value, and most of the drugs in this category are opioids such as morphine and dilaudid. Prescriptions for these medications are limited in the amount that can be prescribed and the prescription cannot be “called in.” Restrictions on prescriptions decrease as the schedule level decreases.

With the passage of the Controlled Substances Act, cannabis was wrongly placed in Schedule I. Responding to questions about the placement of marijuana in Schedule I, President Richard Nixon appointed experts to review the science and report back. This Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, commonly referred to as the Shafer Commission (for its chairman), released its findings in a document, Marijuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding, which found that cannabis did not meet criteria for Schedule I (National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, 1972). However, Nixon ignored the commission’s findings, and cannabis remained forbidden.

Numerous challenges to the cannabis prohibition arose over the years. The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) submitted a petition to reschedule marijuana to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1972 (Randall, 1988). Years later, the Alliance for Cannabis Therapeutics (ACT) joined the petition, and finally in 1988 the DEA’s administrative law judge, Francis Young, ruled on the petition that marijuana should be moved to Schedule II (Young, 1988). However the head of the DEA, John Lawn, ignored the judge’s ruling and the prohibition of marijuana continued.

Back in the late 1970s, Robert Randall, a glaucoma patient, was arrested for growing marijuana on his back porch in Washington, DC. After a long federal court case he was found not guilty through a medical necessity defense (Randall and O’Leary, 1998). Randall was able to prove that cannabis was the only medication that could control his intraocular pressure and thus prevent blindness. Randall’s law firm managed to get him into the Compassionate Investigational New Drug (IND) program. Randall would receive medical marijuana in rolled cigarette form from the federal government for free. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) allows the University of Mississippi to grow marijuana for research on its dangers, and this marijuana farm was the source of Randall’s medication.

Randall did not remain silent. He and his wife formed the Alliance for Cannabis Therapeutics (ACT) in 1981, with the goal of helping other patients gain legal access to cannabis (Randall & O’Leary, 1998). By 1992 the AIDS epidemic was universally acknowledged, and hundreds of applications for the IND program were being submitted for HIV-positive patients. Alarmed by the increased demand for cannabis, the Secretary of Health and Human Services closed access to it. At the time there were 15 patients in the program, and only they would be allowed to receive the medication. Today only 4 of those patients are still alive and only 2 remain in the program because the treating physician for the 2 Iowa patients relocated, leaving them with no physician willing to seek a Schedule I license from the DEA.

Patient awareness of the therapeutic potential of cannabis continued to grow, and desperate patients began helping each other. Cannabis buyers’ clubs began to appear around the country. Patients would grow cannabis or find someone to grow it and then provide it to other patients in need. The buyers’ clubs (now often referred to as compassion clubs or dispensaries) required patients to provide evidence that they had a medical need for cannabis, and in many cities (eg, San Francisco) law enforcement looked the other way. Finally in 1996 California voters passed Proposition 215, which permitted patients to grow and use cannabis as medication if they had a recommendation from a physician.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued a report in 1999 that examined potential therapeutic uses for marijuana. The report found that

Scientific data indicate the potential therapeutic value of cannabinoid drugs, primarily THC, for pain relief, control of nausea and vomiting, and appetite stimulation; smoked marijuana however, is a crude THC delivery system that also delivers harmful substances. The psychological effects of cannabinoids, such as anxiety reduction, sedation, and euphoria can influence their potential therapeutic value. Those effects are potentially undesirable for certain patients and situations and beneficial for others. In addition, psychological effects can complicate the interpretation of other aspects of the drug’s effect. (Joy et al., 1999)

Further studies have found that marijuana is effective in relieving some of the symptoms of HIV/AIDS, cancer, glaucoma, and multiple sclerosis. In early 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a report based on the review of over 10,000 scientific abstracts from marijuana health research. They also made a hundred conclusions related to health and suggested ways to improve cannabis research.

By 2019, 33 states (Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, and Washington, West Virginia) plus Washington DC, Guam, and Puerto Rico have medical marijuana/cannabis laws.

Eleven states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, Washington) and the District of Columbia, the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam have legalized cannabis for recreational use; however, cannabis remained forbidden under federal law and patients are still at risk for federal prosecution. In addition, 14 other states have passed CBD-only cannabis laws due to its success with pediatric seizure disorders and pleas from desperate parents.

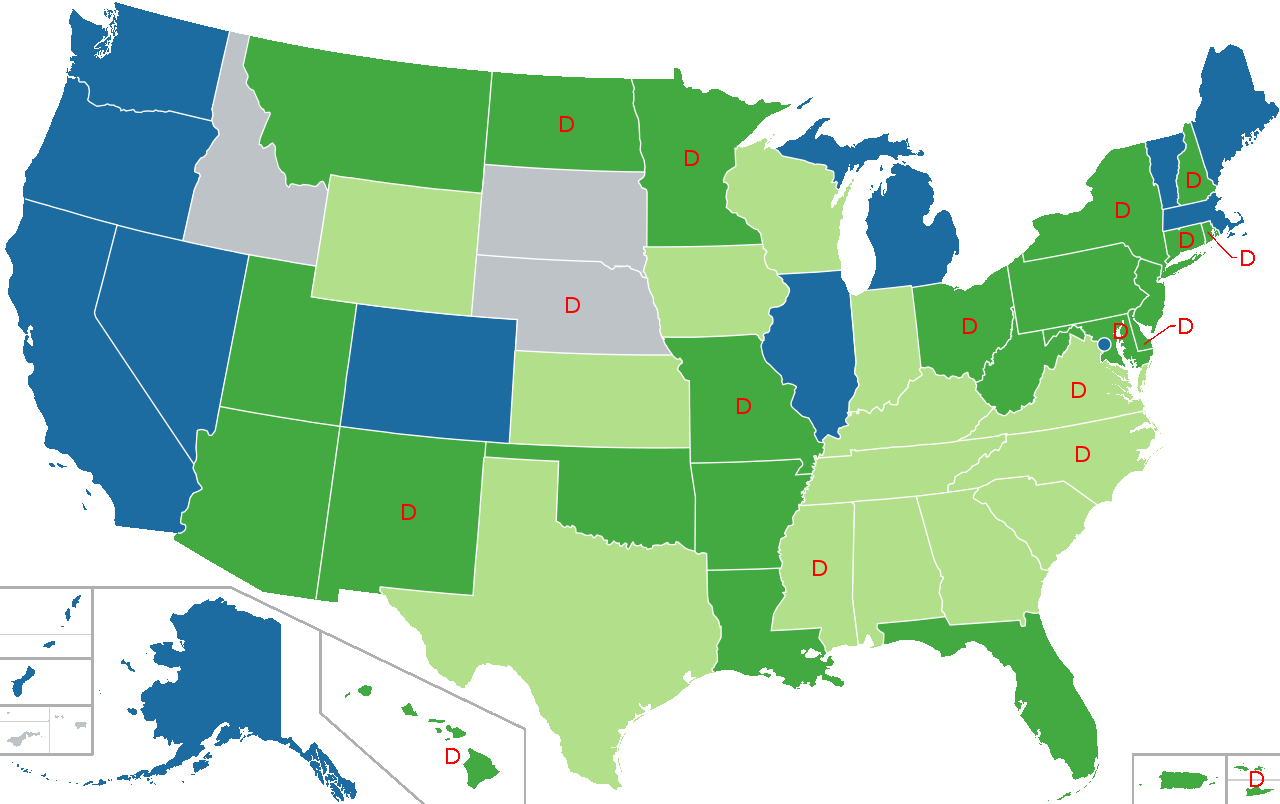

Legal Status of Cannabis in the United States

Legal Legal for medical use

Legal for medical use, limited THC content

Prohibited for any use D (Decriminalized)

Map showing legal status of medical cannabis in the United States.

Blue = No doctor’s recommendation required

Dark green = Doctor’s recommendation required

Light green = Limited THC content

Gray = Prohibited

Lokal_Profil / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5) Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

States with Therapeutic Marijuana Use Laws (as of June 2019) |

States That Have Legalized Recreational Use1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

State | Date of Enactment |

State | Date of Enactment |

California | 1996 |

Colorado | 2014 |

Alaska | 1998 |

Washington | 2014 |

Oregon | 1998 |

District of Columbia | 2014 |

Washington | 1998 |

Alaska | 2015 |

Colorado | 2000 |

Oregon | 2015 |

Hawaii | 2000 |

California | 2016 |

Nevada | 2000 |

Maine | 2016 |

Vermont | 2004 |

Massachusetts | 2016 |

New Mexico | 2008 |

Nevada | 2016 |

Michigan | 2008 |

Michigan | 2018 |

Rhode Island | 2009 |

Illinois | 20202 |

New Jersey | 2009 |

|

|

Arizona | 2010 |

||

Maine | 2010 |

||

Delaware | 2011 |

||

Montana | 2011 |

||

Connecticut | 2012 |

||

Maryland | 2013 |

||

Massachusetts | 2013 |

||

New Hampshire | 2013 |

||

Illinois | 2014 |

||

Minnesota | 2014 |

||

New York | 2014 |

||

Utah | 2014 |

||

Louisiana | 2015 |

||

Ohio | 2016 |

||

Pennsylvania | 2016 |

||

Arkansas | 2016 |

||

North Dakota | 2016 |

||

Florida | 2017 |

||

Missouri | 2018 |

||

Oklahoma | 2018 |

||

West Virginia | 2018 |

||

Because cannabis remains in Schedule I, physicians (and, in some states, nurse practitioners) cannot write a prescription for this medication even in states where it is lawful, but instead are allowed to “recommend” cannabis for certain conditions. Doctors with the Department of Veterans Affairs, even in states where medical cannabis is legal, cannot even discuss marijuana as an option with patients.

The Rohrabacher-Farr amendment prohibits the Justice Department from spending funds to interfere with the implementation of states’ medical cannabis laws. It passed after six attempts (beginning in 2001) and became law in 2014. It was the first time Congress voted to protect medical cannabis patients and was viewed as a historic victory at the federal level for cannabis reform advocates. The amendment must be renewed each fiscal year to remain in effect (Lopez, 2014).

In 2002 the Coalition to Reschedule Cannabis submitted another petition to the DEA to reschedule cannabis (see www.drugscience.org). It demanded that cannabis be removed from Schedule I because the current scientific evidence shows that it does have accepted medical value. After holding it for three years, the DEA finally passed the Petition on to the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) for their scientific review. The DHHS held onto the petition for years and finally in 2011 they denied any medical value with cannabis and thus, the DEA rejected the petition.

The Deputy Director for Regulatory Programs at the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) said at a June 2014 congressional hearing that the agency was analyzing whether marijuana should be downgraded, at the request of the DEA (Edney, 2014). In August 2016, the DEA reaffirmed its position and refused to remove Schedule I classification (Washington Post, 2017). DEA announced in 2016 that it would end restrictions on the supply of marijuana to researchers and drug companies that had previously only been available from the government’s own facility at the University of Mississippi; however, the supply of research grade cannabis is limited to one approved source (W. Post, 2017; Californian, 2017).

The Democratic Party’s 2016 platform called for removal of marijuana from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act:

Because of conflicting federal and state laws concerning marijuana, we encourage the federal government to remove marijuana from the list of “Schedule 1” federal controlled substances and to appropriately regulate it, providing a reasoned pathway for future legalization (Democratic Platform Committee, 2016).

Several House bills introduced in 2017 sought to reschedule cannabis to Schedule II or Schedule III, but were unsuccessful. In May 2017 the American Legion, a conservative veterans’ group, petitioned the White House for a meeting to discuss rescheduling or descheduling cannabis and allowing it to be used medically, particularly to facilitate research into whether cannabis can help veterans experiencing post traumatic stress disorder (Bender, 2017).

In July 2017 a lawsuit was brought in U.S. District Court against the heads of the DEA and Justice Department on the grounds that Schedule I listing of cannabis is “so irrational that it violates the U.S. Constitution” (Pasquariello, 2017). The lawsuit was dismissed; however, in May 2019, a federal appeals court has reinstated the 2017 case against the federal government over the Schedule I status of cannabis. The plaintiffs argued that cannabis’ Schedule I status represented a risk to patients’ health and perpetuated economic iniquities in the United States.

Attorney Michael Hiller, who represents the plaintiffs, said the court has directed the DEA and federal government to act on the plaintiffs’ de-scheduling petition “with all deliberate speed”(Hasse, 2019).

The 2018 United States farm bill descheduled some cannabis products from the Controlled Substances Act for the first time (Teaganne et al., 2018).

If cannabis is removed from Schedule I, other states will be able to allow the medical use of cannabis and patients will no longer be under threat of federal prosecution.

In addition, each state that has a medical cannabis law has the legal authority to challenge the federal government based on the understanding that state laws trump federal regulations regarding medical practice. The medical marijuana states have allowed the use of cannabis, therefore there is “accepted medical use in the United States” and that justifies the removal of cannabis from Schedule I. Unfortunately, no state government has made this challenge due to a lack of understanding of the law or fear of challenging the federal government (and possibly losing federal funds).

Healthcare professionals today are caught in a legal and ethical bind. Numerous state healthcare associations have passed resolutions that recognize the safety and efficacy of cannabis and support patient access to this medication.

In 2003 the American Nurses Associations (ANA) passed a similar resolution. They reaffirmed their position on medical cannabis in 2008 and in 2016, stating the ANA strongly supports:

- Scientific review of marijuana’s status as a federal Schedule I controlled substance and relisting marijuana as a federal Schedule II controlled substance for purposes of facilitating research.

- Development of prescribing standards that includes indications for use, specific dose, route, expected effect and possible side effects, as well as indications for stopping a medication.

- Establishing evidence-based standards for the use of marijuana and related cannabinoids.

- Protection from criminal or civil penalties for patients using therapeutic marijuana and related cannabinoids as permitted under state laws.

- Exemption from criminal prosecution, civil liability, or professional sanctioning, such as loss of licensure or credentialing, for health care practitioners who discuss treatment alternatives concerning marijuana or who prescribe, dispense or administer marijuana in accordance with professional standards and state laws. (ANA, 2016)

Because of its Schedule I placement, healthcare professionals cannot legally help their patients obtain cannabis and cannot themselves possess it.

In the meantime, patients are using cannabis and healthcare professionals have an obligation to provide education on its risks and benefits. This course presents evidence-based information about the safety and efficacy of cannabis and introduces the emerging science on the endogenous cannabinoid system. By understanding the science, healthcare professionals can be empowered to help end the prohibition of cannabis, which will not only allow legal access for the medicinal use but also permit quality control of this medication.