*This course has been retired. Do not take this course! Please click here for an updated version of this course.

Mental health has traditionally been the purview of psychiatrists and specifically trained mental health practitioners. But over the last two to three decades, family practice physicians, nurse practitioners, allied health professionals, and other healthcare providers are increasingly responsible for identifying and managing chronic mental health problems including suicidal ideation and behaviors.

Now it is not uncommon for a variety of healthcare providers to find themselves at the front lines of identifying serious mental health issues that require screening and referral. Because of these changes, it is important that all healthcare providers are knowledgeable about suicide risk factors and warning signs, understand suicide screening tools, and know when, where, and how to refer a client who is at risk for self-harm.

Defining Terms

- Suicide is defined as death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with intent to die as a result of the behavior.

- A suicide attempt is a non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behavior with intent to die as a result of the behavior. A suicide attempt might not result in injury.

- Suicidal ideation refers to thinking about, considering, or planning suicide.

Source: CDC, 2016.

Suicide Is a Major Public Health Concern

In the United States, approximately 45,000 people die from suicide each year, making it the country’s tenth leading cause of death. It is not limited to any one age, socioeconomic or ethnic group, or to one gender (CDC, 2018).

A web of biological, psychological, social, environmental, and situational concerns influence suicidal ideation and behavior. Childhood trauma, substance abuse, poverty, and untreated mental health problems are common risk factors. Unfortunately, many people cannot get help because of provider shortages, stigma associated with mental illness, and the cost of care (WSDOH, 2016).

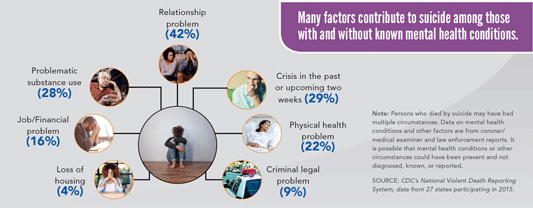

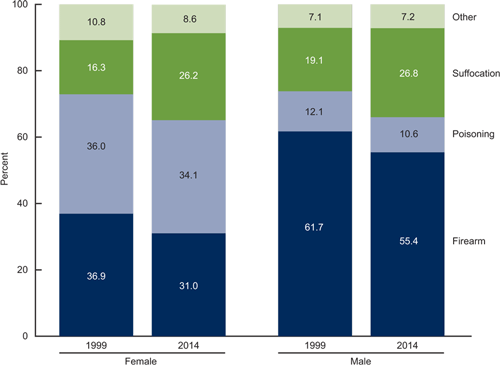

A CDC Vital Signs report examined state-level trends in suicide rates from 1999 to 2016, which found that more than half of people who died by suicide did not have a known diagnosed mental health condition at the time of death. Relationship problems or loss; substance misuse; physical health problems; and job, money, legal or housing stress often contributed to risk for suicide. Firearms were the most common method of suicide used by those with and without a known diagnosed mental health condition (CDC, 2018).

Factors Contributing to Suicide

Source: CDC’s National Vital Statistics System. Public Domain.

Original (larger) image is at this URL: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/

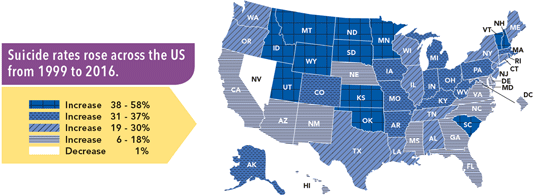

Washington State, along with other Western states (excluding California), has some of the highest rates of suicide in the country. Over the past 20 years, Washington has experienced a nearly 19% increase in suicides (CDC, 2018). Strikingly, in 2016 there were many more suicides (45,000) in the United States than homicides (17,793) (CDC, 2017a).

U.S. Suicide Rates, 1999–2016

Source: CDC’s National Vital Statistics System. CDC Vital Signs. June 2018.

Original (larger) image is at this URL: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/

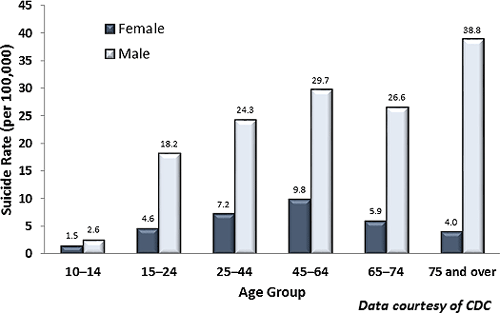

Among children age 10 to14, suicide is the third leading cause of death. Among older teenagers and young adults age 15 to 34, suicide is the second leading cause of death (CDC, 2017a).

Suicide attempts are more frequent among women, although men have a higher rate of completed suicides. Men often use particularly lethal methods such as shooting, hanging, or suffocation, while women often attempt suicide by poisoning, wrist cutting, or falling from heights (Mendez-Bustos et al., 2013).

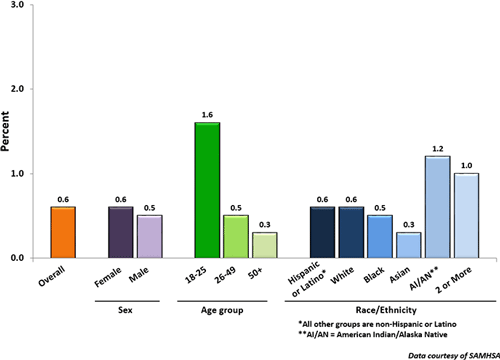

Prevalence of Suicide Attempts Among U.S. Adults (2015)

Source: Data courtesy of SAMHSA, 2015.

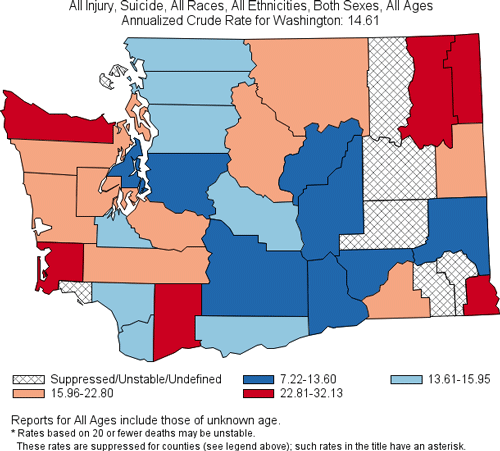

In Washington State the suicide rate is 11% higher than the national average: from 2010 to 2014, over 5,000 people died as a result of suicide (WSDOH, 2016). Three Washingtonians die by suicide every day, and in an average week there are 65 hospitalizations from self-inflicted injury.

From 2010 to 2014, suicide rates were higher than the state rate in six counties:

- Clallam

- Grays Harbor

- Okanogan

- Pierce

- Skamania

- Stevens (WSDOH, 2016)

2008–2014, Washington Death Rates per 100,000 Population

Produced by: the Statistics, Programming & Economics Branch, National Center for Injury Prevention & Control, CDC.

Data sources: NCES National Vital Statistics System for numbers of deaths; US Census Bureau for population estimates.

Although the suicide rate in King County (Washington’s most populated county) is lower than the state rate, it has the largest population and the highest number of suicides in the state (WSDOH, 2016).

Seven counties in Washington have small populations and had too few suicides to calculate a suicide rate. This does not mean that there are not suicides in these counties; county-level data do not always accurately reflect suicide losses in communities.* For example, in 2013 both the Spokane Tribe of Indians and the Colville Confederated Tribes declared a suicide state of emergency because of high numbers of suicide deaths. Clark County’s Battle Ground School District, located in a town of fewer than 18,000 residents, lost seven students to suicide between 2011 and 2013. Neither pattern of loss was clear from a glance at county data (WSDOH, 2016).

*Suicide rates vary in different parts of Washington but because of the way rates are compared, a small difference may be statistically significant while a larger one is not. Statistical significance means the difference is very unlikely to be due to chance.

Key Points About Suicide

- Suicide is a preventable public health problem, not a personal weakness or family failure.

- Prevention is not the responsibility of the health system alone.

- Silence and stigma about suicide harm individuals, families, and communities.

- Suicide does not affect all communities equally or in the same way.

- Prevention programs should reflect community needs and local cultures.

Source: Washington State Department of Health, 2016.

Firearm Fatality and Suicide Prevention: A Public Health Approach

On January 6, 2016, Governor Jay Inslee issued Executive Order 16-02 (EO 16-02) recognizing the need to take a public health approach to reduce firearm fatalities and suicides. The Executive Order also introduced the Washington State Suicide Prevention Plan and highlighted how it would play a role in addressing this need.

The executive order directs state government agencies to:

- Collect, review, and disseminate data on deaths and injury hospitalizations attributed to firearms and make recommendations as to specific prevention and safety strategies to reduce these fatalities and serious injuries.

- Conduct a gap analysis to determine the effectiveness of statutorily mandated information sharing between the courts, local jurisdictions, and law enforcement.

- Begin implementation of the Statewide Suicide Prevention Plan.

- Promote depression and suicide risk screening tools.

- Begin a social marketing campaign prioritizing populations with the highest risk to raise suicide awareness and prevention.

- Focus on recommendations coming from a gap analysis of existing programs specific to our schools, Veteran, and Native American and Alaskan Native communities to provide effective, culturally appropriate crisis intervention and treatment services.

- Update a 2007 white paper on firearm access by persons prohibited from possessing a firearm due to involuntary commitment.

Source: Washington State Department of Health, 2018.

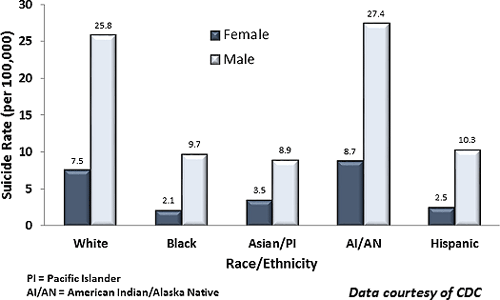

Suicide Rates by Race/Ethnicity, Age, and Gender

In Washington, suicide rates are highest among American Indian, Alaska Native, and white populations, consistent with national rates. For American Indian youth, the suicide rate is more than double the white non-Hispanic rate and more than triple the rates for the other racial/ethnic groups (CSAT, 2015).

Among African Americans nationwide, the suicide rate is 70% lower than that of the non-Hispanic white population. The suicidedeath rate for African American men was more than four times greater than for African American women (OMH, 2017). Suicide risk peaks in the early twenties for African American males and the late twenties for females (Wang et al., 2016).

Among the six largest Asian American subgroups,* Korean males have more than twice the frequency of death due to suicide (5%) compared to non-Hispanic whites (2%). Suicide rates in Korean Americans have nearly doubled from 2003 to 2012 and exceed rates for all other Asian American subgroups (Kung et al., 2018). Suicide is the fifth leading cause of death for Korean males, higher than every other Asian subgroup as well as non-Hispanic Whites (Hastings et al., 2015).

*Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese.

Hispanics/Latinos have fairly similar rates of suicidal behaviors compared with white, non-Hispanic individuals. The prevalence of suicidal behavior increases among youth and young adults who are more acculturated to mainstream American culture, particularly among females (CSAT, 2015). A nationwide survey of high school students found Hispanic youth were more likely to report attempting suicide than their African American or white, non-Hispanic peers (CDC, 2017b).

Suicide Rates by Race/Ethnicity in the United States (2014)

Source: Data courtesy of CDC.

Nationally, the suicide rate for teens and young adults has nearly tripled since the 1940s. Throughout the United States, suicide is the third leading cause of death for youth between the ages of 10 and 24 (approximately 4,600 lives lost each year). Of the reported suicides in the 10 to 24 age group, 81% of the deaths were males and 19% were females. Boys are more likely than girls to die from suicide while girls are more likely to attempt suicide (CDC, 2017b).

Be Alert to Signs of Suicide Ideation

Self-injury is deliberate harm inflicted on a person’s own body.

Source: Military OneSource.

Among youth, non-suicidal, self-injurious behaviors such as cutting, burning, hitting oneself, scratching to the point of bleeding, or interfering with healing can occur together with suicidal behaviors. It is important to consider the nature of the link between these two types of behavior (Grandclerc et al., 2016).

In Washington, men account for more than three-quarters of suicide deaths. From 2012 to 2014, men 75 and older had the highest rate of suicide while men 45 to 64 had the highest number of suicides. For older men, contributing factors include economic insecurity, loss of significant relationships, loneliness, fear of being a burden, and the physical and mental stresses of aging (WSDOH, 2016).

Suicide Deaths, by Method and Sex: United States, 1999 and 2014

Source: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality, 2016.

In recent years, suicide rates for middle-aged women have increased by more than 30%, exceeding the increases observed among middle-aged men. However, using data from the Nurses’ Health Study, researchers determined women who were socially well integrated* had a more than 3-fold lower risk for suicide over 18 years of followup (Tsai et al., 2015).

*Social integration was measured with a 7-item index that included marital status, social network size, frequency of contact with social ties, and participation in religious or other social groups (Tsai et al., 2015).

Suicide Rates by Age in the United States (2014)

Source: Data courtesy of CDC.

Veterans, Immigrants, and Refugees

When compared to other Americans, there are some differences in the rates and patterns of suicidal behavior among U.S. veterans. This includes:

- Increases in rate of suicide among younger veterans (18–29 years of age)

- Gender-based differences (changes in rates among women veterans)

- A comparatively high prevalence (approximately 66%) of suicides resulting from a firearm injury (USDVA, 2016a)

Among veterans returning from the current wars, one of the most common mental health diagnoses is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is a known risk factor for both suicidal ideation and behavior. Major depressive disorder, which is highly comorbid with PTSD, independently increases risk for suicidal ideation and attempts (DeBeer et al., 2016).

For people migrating to the United States, stress associated with migration can be a risk factor for suicidal ideation and behaviors (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013). Roughly 1 in 7 residents of Washington State is an immigrant, accounting for nearly 14% of the state’s population (American Immigration Council, 2017). From 2010 to 2016, Washington State admitted more than 16,000 refugees from 46 countries. Seventy-two percent of the state’s refugees came from just five countries: Iraq, Myanmar, Somalia, Bhutan, and Ukraine (McDermott, 2016).

Ending ties with their country of origin, loss of status and social networks, language barriers, unemployment, financial problems, a sense of not belonging, and feelings of exclusion can lead to depression, anxiety, PTSD, alcohol and drug abuse, loneliness, and hopelessness. Migration can also pose a risk for the families who remain in the country of origin. Emigration can weaken family ties, lead to feelings of loneliness and insecurity, and increase the risk of suicide among family members who remain at home (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).

Refugees, one of the most vulnerable groups of all immigrants, are often fleeing war, torture, and persecution, and suffering with PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Lack of adequate preparation, the way in which they are received in the destination country, poor living conditions, lack of social support, and isolation add to these vulnerabilities. Refugees may also feel guilty for leaving loved ones at home. The sense of guilt, together with isolation and pathologic symptoms due to trauma, may be a strong risk factor for suicide (Ratkowska & De Leo, 2013).