Please click here to go to the most recent version of this course

The use of engineering and work practice controls to reduce the opportunity for patient and healthcare worker exposure to potentially infectious material should be standard practice in all healthcare settings, not only in hospitals. Facilities are required to address and manage high-risk practices and procedures capable of causing healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs) from bloodborne pathogens.

[The following information is taken from the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, 1910.1030.]

Engineering controls such as sharps disposal containers, self-sheathing needles, and safer medical devices (sharps with engineered sharps injury protections and needleless systems) isolate or remove the bloodborne pathogens hazard from the workplace.

Work practice controls reduce the likelihood of exposure by altering the manner in which a task is performed (e.g., prohibiting recapping of needles by a two-handed technique).

Engineering and work practice controls are intended to eliminate or minimize employee exposure. They must be examined and maintained or replaced on a regular schedule to ensure their effectiveness. Engineering controls usually involve an object, such as a safer chemical, syringe with engineered safety protection, sharps container, or splash guard. Work practice controls reduce risk by altering the way a task is performed. Work practice controls tell how to do the job safely, and should be described in written procedures. Engineering and work practice controls are designed to reduce risk of percutaneous, mucous membrane/non-intact skin or parenteral exposures of workers.

Percutaneous (through the skin) exposures can occur during handling, disassembly, disposal, and reprocessing of contaminated needles and other sharp objects, or via human bites, cuts, and abrasions.

Activities which risk percutaneous exposures include manipulating contaminated needles and other sharp objects by hand, removing scalpel blades from holders, and removing needles from syringes can lead to a percutaneous injury.

Delaying or improperly disposing of sharps, leaving contaminated needles or sharp objects on counters or workspaces, or disposing of sharps in nonpuncture-resistant receptacles can lead to injury. Recapping contaminated needles and other sharp objects using a two-handed technique is a common cause of injury. Percutaneous exposures can also occur when performing procedures where there is poor visualization—such as blind suturing, non-dominant hand positioned opposed or next to a sharp, and performing procedures where bone spicules or metal fragments are produced.

Mucous membrane/non-intact skin exposures occur when there is direct blood or body fluids contact with the eyes, nose, mouth, or other mucous membranes. This can occur via contact with contaminated hands, contact with open skin lesions/dermatitis, and from splashes or sprays of blood or body fluids (e.g., during irrigation or suctioning).

Parenteral refers to a route of transmission or administration that involves piercing mucous membranes or the skin barrier through such events as needlesticks, human bites, cuts, and abrasions. A parenteral exposure occurs as a result of injection with infectious material, which can occur during administration of parenteral medication, sharing of blood monitoring devices such as glucometers, hemoglobinometers, lancets, and lancet platforms/pens, and infusion of contaminated blood products or fluids.

According to OSHA, nurses sustain the most needlestick injuries, and as many as one-third of all sharps injuries occur during disposal. The CDC estimates that 62% to 88% of sharps injuries can be prevented simply by using safer medical devices.

Safe Injection Practices: Protecting Patients

Needles, cannulas, and syringes are sterile, single-use items—any use will result in these items being contaminated. They are contaminated once they are used to enter or connect to any component of a patient’s intravenous infusion set. After use, immediately dispose of all needles and syringes into a leak-proof, puncture-resistant, closable container. Develop policies and procedures to prevent sharps injuries among staff and review them regularly.

Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens from needlesticks and other sharps injuries is a serious problem, resulting in approximately 385,000 needlesticks and other sharps-related injuries to hospital-based healthcare personnel each year. Similar injuries occur in other healthcare settings, such as nursing homes, clinics, emergency care services, and private homes. Sharps injuries are primarily associated with occupational transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but they have been implicated in the transmission of more than 20 other pathogens. The resources on this website have been developed by CDC to help healthcare facilities prevent needlesticks and other sharps-related injuries to healthcare personnel (CDC, 2015).

Medications and Solutions

A pathogen can be indirectly transmitted through contaminated medications and injection equipment. For this reason, medications and solutions must be properly handled whether they are single or multidose. To prevent cross contamination, preparation and disposing of medications should be handled in areas designated for that purpose.

The reuse of needles or syringes and the misuse of medication vials are serious threats to public health. Healthcare providers should never reuse a needle or syringe, either from one patient to another or to withdraw medicine from a vial. Both needle and syringe must be discarded once they have been used. It is not safe to change the needle and reuse the syringe—reuse of needles or syringes to access medication can result in contamination of the medicine with infectious material that can be spread to others when the medicine is used again (CDC, 2010).

Injectable Device

Neither portion of the injectable device may be reused under any circumstances. Source: CDC, 2010. Public domain.

Single-Dose Vials

A single-use vial is a bottle of liquid medication that is given to a patient through a needle and syringe. Single-use vials contain only one dose of medication and should only be used once for one patient, using a clean needle and clean syringe. Use single-dose vials for parenteral medications whenever possible. Do not administer medications from single-dose vials or ampoules to multiple patients or combine leftover contents for later (CDC, 2010).

Multidose Vials

A multidose vial is a small sealed container holding more than one dose of medication, vaccine or fluid. The advantages of multidose vials include being able to adjust dosage of medication easily, less waste of left-over medication, cost savings in packaging, and ease of use. For the medication to remain sterile and safe for use between patients, a new sterile needle and syringe must be used every time the vial is entered.

To prevent breaches of recommended practices, minimize the use of multidose vials whenever possible. If multidose vials must be used, always use aseptic technique. Use a new needle or cannula and a new syringe to access the multidose vial. Do not keep the vials in the immediate patient treatment area. Do not use bags or bottles of IV solution as a common source of medication or fluid for multiple patients. Use infusion sets (i.e., intravenous bags, tubing, and connectors) for one patient only and dispose appropriately after use (CDC, 2019c). For more on multidose use of vials, click here.

Aseptic Technique

Aseptic technique involves the handling, preparation, and storage of medications in a manner that prevents microbial contamination. It also applies to the handling of all supplies used for injections and infusions, including syringes, needles, and IV tubing. To avoid contamination, medications should be drawn up in a clean medication preparation area. Any item that may have come in contact with blood or bodily fluids should be kept separate from medications. Incorrect practices that have resulted in transmission of hepatitis C or hepatitis B virus include using:

- The same syringe to administer medication to more than one patient, even if the needle was changed

- The same medication vial for more than one patient, and accessing the vial with a syringe that has already been used to administer medication to a patient

- A common bag of saline or other IV fluid for more than one patient, and accessing the bag with a syringe that has already been used to flush a patient’s catheter

In addition to strictly adhering to aseptic technique, ensure that all staff perform proper hand hygiene before and after gloving, between patients, and whenever hands are soiled. Avoid cross contamination with soiled gloves. Provide adequate soap and water, disposable paper towels, and waterless alcohol-based hand rubs throughout all medical facilities (CDC, 2019c).

Safe Injection Practices

[This section is derived largely from CDC, 2015.]

Safe injection practices are designed to prevent disease transmission from patient to patient and healthcare worker to patient. The absence of visible blood or signs of contamination in a used syringe, IV tubing, multidose medication vial, or blood glucose monitoring device does not mean the item is free from potentially infectious agents. Bacteria and other microbes can be present without clouding or other visible evidence of contamination. All used injection supplies and materials are potentially contaminated and should be discarded.

Many cases reported to the CDC in which a bloodborne pathogen was transmitted as a result of improper injection practices have common themes and findings. Often aseptic technique and Standard Precautions were not carefully followed. In many cases infection control programs were lacking or responsibilities were unclear. Lack of recognition of an IC breach led to prolonged transmission and a growing number of infected patients. In all cases, investigations were time-consuming and costly and required the notification, testing, and counseling or hundreds and sometimes thousands of patients.

To ensure safe injection practices, providers should use aseptic technique throughout all aspects of injection preparation and administration. Medications should be drawn up in a designated “clean” medication area that is not adjacent to areas where potentially contaminated items are placed. In addition:

- Use a new sterile syringe and needle to draw up medications for each patient. Prevent contact between the injection materials and the non-sterile environment.

- Practice proper hand hygiene before handling medications.

- Disinfect the rubber septum of a medication vial with alcohol prior to piercing.

- Discard medication vials upon expiration or any time there are concerns regarding the sterility of the medication.

Never leave a needle or other device inserted into a medication vial septum, IV bag, or bottle for multiple uses. This provides a direct route for microorganisms to enter the vial and contaminate the fluid. Medications should never be administered from the same syringe to more than one patient, even if the needle is changed. Never use the same syringe or needle to administer IV medications to more than one patient, even if the medication is administered into the IV tubing, regardless of the distance from the IV insertion site.

Keep in mind that all of the infusion components from the infusate to the patient’s catheter are a single interconnected unit. All of the components are directly or indirectly exposed to the patient’s blood and cannot be used for another patient. Syringes and needles that intersect through any port in the IV system also become contaminated and cannot be used for another patient or used to re-enter a nonpatient-specific multidose vial. Separation from the patient’s IV by distance, gravity, or positive infusion pressure does not ensure that small amounts of blood are not present in these items.

Dedicate vials of medication to a single patient. Never enter a vial with a syringe or needle that has been used for a patient if the same medication vial might be used for another patient. Medications packaged as single-use must never be used for more than one patient. Never combine leftover contents for later use. Medications packaged as multi-use should be assigned to a single patient whenever possible. Never use bags or bottles of IV solution as a common source of supply for more than one patient.

Peripheral capillary blood monitoring devices packaged for single-patient use should never be used on more than one patient. Restrict use of peripheral capillary blood sampling devices to individual patients. Never reuse lancets. Consider selecting single-use lancets that permanently retract upon puncture. Whenever possible evaluate and select safer devices to prevent sharps injuries.

Sharps Safety: Protecting Healthcare Workers

[This section is derived from CDC, 2015a.]

There has been increased focus on removing sharps hazards through the development and use of engineering controls. In November 2000 the Federal Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act authorized OSHA’s revision of its Bloodborne Pathogens Standard to require the use of safety-engineered sharp devices (see below). The CDC has provided guidance on the design, implementation, and evaluation of a comprehensive sharps injury prevention program. This includes measures to handle needles and other sharp devices in a manner that will prevent injury to the user and to others who may encounter the device during or after a procedure.

Healthcare workers must follow proper technique when using and handling needles, cannulas, and syringes. Whenever possible, use sharps with engineered sharps injury protections—for example, non-needle sharp or needle devices with built-in safety features or mechanisms that effectively reduce the risk of an exposure incident. Do not disable or circumvent the safety feature on devices.

Always activate safety features—do not circumvent them. Modify procedures if necessary to avoid injury. For example:

- Use forceps, suture holders, or other instruments for suturing.

- Avoid holding tissue with fingers when suturing or cutting.

- Avoid leaving exposed sharps of any kind on patient procedure or treatment work surfaces.

- Use appropriate safety devices whenever available.

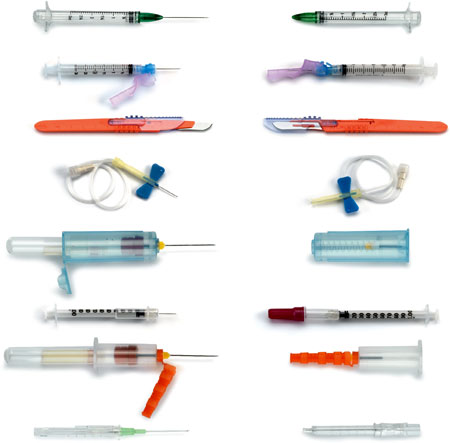

Examples of Sharps with Safety Features Exposed and Covered

Source: CDC. Public domain.

In surgical and obstetrical settings where the use of exposed sharps cannot be avoided, work-practice controls are an important adjunct for preventing blood exposures, including percutaneous injuries. Operating room controls include:

- Using instruments, rather than fingers, to grasp needles, retract tissue, and load/unload needles and scalpels

- Giving verbal announcements when passing sharps

- Avoiding hand-to-hand passage of sharp instruments by using a basin or neutral zone

- Using alternative cutting methods such as blunt electrocautery and laser devices when appropriate

- Substituting endoscopic surgery for open surgery when possible

- Using round-tipped scalpel blades instead of sharp-tipped blades The use of blunt suture needles, an engineering control, is also shown to reduce injuries in this setting. These measures help protect both the healthcare provider and the patient from exposure to the other’s blood.

Puncture-resistant containers located at the point of use are used to discard sharps, including needles and syringes, scalpel blades, unused sterile sharps, and discarded slides or tubes with small amounts of blood. To prevent needlestick injuries, needles and other contaminated sharps should not be recapped, purposefully bent, or broken by hand.

As part of their responsibility for providing a safe workplace, employers must provide handwashing facilities that are readily accessible to employees. If it is not feasible to provide handwashing facilities, the employer must provide antiseptic hand cleanser and clean cloth or paper towels, or antiseptic towelettes. When antiseptic hand cleansers or towelettes are used, hands should be washed with soap and running water as soon as possible.

Work Practice Controls: How to Do the Job Safely

Contaminated needles and other contaminated sharps should not be bent, recapped, or removed unless the employer can demonstrate that there is no alternative or that such action is required by a specific procedure. Shearing or breaking of contaminated needles is prohibited.

Any required manipulation must be accomplished through the use of a mechanical device or a one-handed technique.

Immediately, or as soon as possible after use, contaminated reusable sharps must be placed in appropriate containers until properly reprocessed. These containers must be:

- Puncture resistant

- Labeled or color-coded in accordance with this standard

- Leakproof on the sides and bottom

- Maintained in accordance with OSHA requirements for reusable sharps

Eating, drinking, smoking, applying cosmetics or lip balm, and handling contact lenses are prohibited in work areas where there is a reasonable likelihood of occupational exposure. Food and drink should not be kept in refrigerators, freezers, shelves, cabinets, or on countertops or bench tops where blood or OPIM are present. It may be useful to designate areas to be kept free of body fluids (no specimens of gloves) where drinks may be permitted.

All procedures involving blood or other potentially infectious materials must be performed in such a manner as to minimize splashing, spraying, spattering, and generation of droplets of these substances. Mouth pipetting or suctioning of blood or OPIM is prohibited.

Specimens of blood or other potentially infectious materials must be placed in a container that prevents leakage during collection, handling, processing, storage, transport, or shipping. The container must be labeled or color-coded according to OSHA guidelines. When a facility utilizes Standard Precautions in the handling of all specimens, the labeling or color-coding of specimens is not necessary provided containers are recognizable as containing specimens, although this exemption only applies while such specimens or containers remain within the facility. Labeling or color-coding is required when such specimens or containers leave the facility.

If outside contamination of the primary container occurs, the primary container must be placed within a second container that prevents leakage during handling, processing, storage, transport, or shipping, and is labeled or color-coded according to the requirements of this standard. If the specimen could puncture the primary container, the primary container shall be placed within a secondary container that is puncture-resistant in addition to the above characteristics.

Equipment that may become contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious materials must be examined before servicing or shipping and be decontaminated as necessary, unless the employer can demonstrate that decontamination of such equipment or portions of such equipment is not feasible. A readily observable label must be attached to the equipment stating which portions remain contaminated.

The employer must ensure that this information is conveyed to all affected employees, the servicing representative, and the manufacturer before handling, servicing, or shipping, so that appropriate precautions will be taken.

Use splatter shields on medical equipment associated with risk-prone procedures (e.g., locking centrifuge lids). Gloves used for the task of sorting laundry should be of sufficient thickness to minimize sharps injuries.

General Practices for the Workplace

- Use proper hand hygiene, including the appropriate circumstances in which alcohol-based hand sanitizers and soap-and-water handwashing should be used.

- Use proper procedures for cleaning of blood and bodily fluid spills, including initial removal of bulk material followed by disinfection with an appropriate disinfectant.

- Practice proper handling and disposal of blood and bodily fluids, including contaminated patient care items.

- Select, put on, take off, and dispose of PPE as trained.

- Protect work surfaces in direct proximity to patient procedure treatment areas with appropriate barriers to prevent instruments from becoming contaminated with bloodborne pathogens.

- Prevent percutaneous exposures by avoiding unnecessary use of needles and other sharp objects.

- Use care in the handling and disposing of needles and other sharp objects.

Evaluation/Surveillance of Exposure Incidents

[Material from this section is taken largely from CDC, 2015b.]

Employers must identify those at risk for exposure and what devices cause exposure. All sharp devices can cause injury and disease transmission if not used and disposed of properly. For example, hollow-bore needles have a higher disease transmission risk, while butterfly-type IV catheters, devices with recoil action, and blood glucose monitoring devices (lancet platforms/pens) have a higher injury rate.

Where Exposures Occur

Sharps injuries don’t just occur in hospitals and labs—they can occur in other healthcare settings, such as nursing homes, clinics, emergency care services, and private homes. Although it is estimated that more than 350,000 sharps injuries occur each year in the United States, the CDC estimates 50% or more of healthcare personnel do not report occupational percutaneous injuries (CDC, 2008). Six sharps devices are responsible for nearly 80% of all injuries. These are:

- Disposable syringes (30%)

- Suture needles (20%)

- Winged steel needles (12%)

- Scalpel blades (8%)

- Intravenous (IV) catheter stylets (5%)

- Phlebotomy needles (3%)

Devices requiring manipulation or disassembly after use (such as needles attached to IV tubing, winged steel needles, and IV catheter stylets) are associated with a higher rate of injury than the hypodermic needle or syringe. Injuries from hollow-bore needles, especially those used for blood collection or IV catheter insertion, are of particular concern. These devices are likely to contain residual blood and are associated with an increased risk for HIV transmission. Overall, hollow-bore needles are responsible for 56% of all sharps injuries (CDC, 2008).

The largest percentage (39%) of sharps injuries occur on inpatient units, particularly medical floors and intensive care units. The operating room is the second most common environment in which sharps injuries occur, accounting for 27% of injuries overall. Injuries most often occur:

- After use and before disposal of a sharp device (40%)

- During use of a sharp device on a patient (41%)

- During or after disposal (15%)

Although nurses sustain the highest number of percutaneous injuries, other patient-care providers, laboratory staff, and support personnel are also at risk. Nurses are the predominant occupational group injured by needles and other sharps, in part because they are the largest segment of the workforce at most hospitals.