*This course has been retired. Please click here for new course, About Suicide: Washington State, 6 units.

Historically, suicide rates have been lower in the military than those rates found in the general population. However, with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, military suicide rates have been increasing and surpassing the rates for society at large. The Army has had the highest proportional number of suicides compared to the other services; however, the rates in all the services have been increasing in recent years (USU, 2016).

In a recent survey, veterans identified suicide as the most formidable challenge they face. Sadly, approximately 22 veterans die by suicide every day. Contributing to this problem, one of the most common mental health diagnoses among veterans returning from the current war theatres is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is a known risk factor for both suicidal ideation and behavior (DeBeer et al., 2016).

A Soldier’s Story

A soldier who had joined the Washington National Guard after returning from deployment came into the Joint Services Support (JSS) office at Camp Murray, asking for help finding a job. While talking with the Employment Transition Team, the soldier revealed financial struggles, fear of returning home because of domestic violence, overwhelming depression, and suicidal thoughts.

The JSS multidisciplinary team sprang into action. Five weeks later the soldier had a regular therapy schedule, gift cards for food and gas, an electronic benefits card, a refreshed résumé, a suicide prevention mentor, an order of protection against the abusive partner, and safe transitional housing. Outstanding disability claims were resolved, and, as the soldier was about to move into an apartment, a job offer came through from a prominent Washington company. The soldier’s life moved from a place of desperation to a place of stability.

It is not unique for a person seeking help to have multiple needs spanning many systems. What is unique is that this soldier had the ability to get all of these needs met in one place by a collaborative, supportive team of professionals, each of whom was well-trained and attuned to depression and suicide risk.

The JSS states that its purpose is to “enhance the quality of life for all Guard members, their families, and the communities in which they live and contribute to readiness and retention in the Washington National Guard.” The JSS at Camp Murray combines strong and supportive leadership, cross-system teamwork, and attention to soldiers’ emotional needs and ability to thrive at work—a program model that improves job performance and saves lives.

Source: WSDOH, 2016.

Veterans: Population-Specific Data

About 13% of Washington’s population has participated in the armed forces. In 2010, the age-adjusted suicide rate among Washington’s veteran or active-duty military members was 55 per 100,000, compared to 15 per 100,000 for those not in the military. From 2000 to 2010, 16% of males and 26% of females in the military who died by suicide were under 35 (WSDOH, 2016).

Information from the Office of Mental Health Operations on causes of death for all veterans who use VHA healthcare services since 2000 shows that rates among VHA users are higher than those of the general population. Users of VHA services account for 1,600 to 1,900 suicides per year, or about 5 per day. Among the deaths from suicide, approximately half had a diagnosis of a mental health condition recorded in their medical records in the year prior to their death, and approximately three-fourths, within the past five years (DVA/DOD, 2013).

The Department of Veterans Affairs reported that in 2014:

- About 67% of all veteran deaths by suicide were the result of firearm injuries.

- About 65% of all veterans who died by suicide were age 50 or older.

- Risk for suicide was 21% higher among veterans when compared with U.S. civilian adults.

- Risk for suicide was 18% higher among male veterans when compared with U.S. civilian adult males.

- Risk for suicide was 2.4 times higher among female veterans when compared with U.S. civilian adult females. (USDVA, 2016b)

Among deployed and non-deployed active-duty veterans who served during the Iraq or Afghanistan wars between 2001 and 2007, the rate of suicide was greatest in the first three years after leaving service. Compared to the U.S. population, both deployed and non-deployed veterans had a higher risk of suicide, but a lower risk of death from all other causes combined (USDVA, 2015).

Contrary to popular belief, while ground services have experienced the stress of repetitive and extended deployments, the 2009 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DODSER) identifies only 7% of military suicides occurred among service members with multiple deployments. The report also stated that while half of those who were military suicides had been deployed at some time to Iraq or Afghanistan, only 17% experienced combat. Another finding is that although senior noncommissioned officers typically experience repetitive deployments, most suicides occur among the junior enlisted (WSDOH, 2016).

Washington’s Healthy Youth Survey data show that children of military families are at higher risk of suicide. A higher percentage of tenth graders with parents in the military reported symptoms of depression in the past year compared to tenth graders from civilian families. They also answered yes more frequently to questions about serious consideration of suicide, making a suicide plan, and attempting suicide, and fewer than half answered yes when asked if there were adults to whom they could turn for help when feeling sad or hopeless (WSDOH, 2016).

Among male veterans, suicide rates are highest in the younger and older years, and among female veterans, suicide rates are highest in the younger years. However, because the age distribution of the living veteran population is heavily weighted toward middle-aged adults, the resulting burden of suicide, in terms of the number of lives lost, is highest among middle-aged veterans, despite the lower rates of suicide observed for this sub-population. Analysis of suicide risk within the veteran population indicates that it is important to develop and direct veteran suicide prevention initiatives that are tailored to reach veterans of all ages (USDVA, 2016b).

Military Culture

But I fear they do not know us. I fear they do not comprehend the full weight of the burden we carry or the price we pay when we return from battle. This is important, because a people uninformed about what they are asking the military to endure is a people inevitably unable to fully grasp the scope of the responsibilities our Constitution levies upon them. . . . We must help them understand, our fellow citizens who so desperately want to help us.

ADM Michael Mullen, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff

United States Military Academy, West Point, 2011

The ability to understand and appreciate military culture and to tailor clinical practices based on that understanding is imperative for clinicians working with service members (USU, 2016). The military is controlled by civilian leaders who involve service members in conflicts not necessarily supported by the majority of civilians, who may not fully understand the impact military service has on individuals and families. There are few opportunities for honest, open, and thoughtful dialogue between civilians and military personnel. Political, cultural, and social differences between civilian and military life can complicate our understanding of the complex issue of suicide (WSDOH, 2016).

The military changes and builds one's identity and espouses values, beliefs, and norms that are quite contrary to civilian life. Close relationships are formed within units, and these become disrupted when soldiers are transferred or moved to other units or when deployment ends. The intensity of such relationships is seldom found in civilian life. Service members can return home with decreased opportunity to participate as intensely in military culture. The transition to civilian life can leave them feeling less integrated and less regulated (WSDOH, 2016).

The warrior ideal is deeply embedded in the psyche of service members. To be unable to live up to this ideal can have significant consequences. Missing one's battle buddies/team, not having a mission, and failing to live up to values and ideals can cause a service member or veteran to feel isolated and inadequate. Many believe that for a warrior to develop symptoms of stress of any kind is a failure to live up to the warrior ideal (Schmidt, 2012).

No matter what branch of service, service members are taught that service comes before self and the mission comes first. Strength, valor, courage, fortitude, honor, esprit de corps, respect, and integrity are considered to be the noble traits of a warrior (Schmidt, 2012).

When a service member leaves the military, they may feel rules begin to disintegrate, leaving feelings of unrest, alienation, anxiety, and lack of purpose. During deployment, family members often become more independent and self-reliant, causing the soldier to feel less needed and believing the family can survive just fine without her or him (WSDOH, 2016).

Source: United States Department of Veteran Affairs.

Military Stress: PFC Wilson

Background

Private First Class Shania Wilson serves in Alpha Company, 181st Brigade Support Battalion, 81t Brigade Combat Team, Washington Army National Guard. A mother of three, she was stationed at Joint Base Balad for eight months, providing security for the hospital and Iraqi business on base, escorting local nationals working on base, and providing Personal Security Detail services.

A second deployment sent Private Wilson to Afghanistan with the 96th Troop Command based out of Yakima. "I wasn't supposed to be on that deployment, but I was called to duty and had to go," she reported. She pulled security duty in a variety of places and on several occasions experienced firefights, witnessed the death of three members of her unit, applied first aid to the severely wounded, and on two occasions experienced two separate blasts from an improvised explosive device.

After her deployments, Private Wilson enrolled in college. Several students in one of her classes surmised she was in the military and she overheard them refer to her one day as a “baby killer.”Recently, a video was shown in her science course that made her feel uncomfortable and since that time she’s had more difficulty concentrating on her studies.

She has not sought any medical or behavioral health assistance for fear that it could interfere with her career in the National Guard and also remove her from the chance to support her unit on another upcoming deployment. In fact, the 81st Brigade Combat Team and 506th Military Police Company received notices of sourcing from the Pentagon, meaning they could be tapped for an upcoming deployment.

Assessment

During a routine medical appointment with a nurse practitioner, the NP noted that Private Wilson kept her eyes down and fidgeted with her cell phone during the initial part of the appointment. When asked how she was feeling, Private Wilson said she was fine except that since returning from her second deployment, she has felt lightheaded with ringing in her ears, has had problems thinking and remembering, and has become more irritable.

“I wasn't supposed to be on that [second] deployment, but I was called to duty and had to go,” she reported. At school, she reported feeling isolated and uncomfortable and said she wasn’t doing well. She said she wasn’t sleeping well and feels hopeless, like there was no reason to live other than her children and unit. She admitted she had begun to drink heavily. She mentioned that she was worried about a possible deployment and had mixed feelings about returning to duty.

Discussion

Private Wilson experienced significant trauma during her deployments, including the death of her fellow service members. She also appears to be experiencing physical and psychological after-effects of being in close proximity to 2 IED blasts. Although she has expressed mixed feelings about a third deployment, she also expressed a sense of duty and a desire to protect her National Guard career.

Test Your Learning

Private Wilson is clearly having difficulty dealing with her experiences in the war. During the patient assessment, what should you do first?

- Tell Private Wilson that it takes time to recover from a military deployment and she will be fine.

- Report Private Wilson to her supervisor at the Washington Army National Guard.

- Determine Private Wilson’s level of risk for suicidal ideation and behavior by asking open-ended, general questions about safety.

- To safeguard Private Wilson’s safety, have her admitted to a psych ward.

Answer: c

Bottom Line

Any healthcare provider may come in contact with someone who may be at risk for self-harm. Don’t be afraid to ask your patients if they’ve ever tried to harm themselves—as well as how many times and in what ways. Have you practiced questions ahead of time that allow you to assess risk, safety, and lethality? Take a moment to ask those questions right now.

Source: Adapted from Schmidt, 2012.

The Veterans Administration has a website for healthcare providers who treat veterans.Healthcare providers can learn about military culture, find links to assessment tools, access information about how to connect with the VA, and learn why they should consider the VA an important member of the treatment team. Mini-clinics on the topics of mental and behavioral health for veterans offer clinicians easy access to useful veteran-focused treatment tools. The mini-clinics provide information on assessment, training, and educational handouts. Click here for mini-clinics for providers.

Veterans: Risk and Protective Factors

A protective factor is anything that makes it less likely for a person to develop a disorder. A risk factor is anything that makes it more likely for a person to develop a disorder or predisposes a person to high risk for self-injurious behaviors. Both protective and risk factors can include biologic, psychological, or social factors in the individual, family, and environment.

Historically, the suicide rate has been lower in the military than among civilians. This protective effect has been thought to be related to a selection bias for healthy recruits, employment, purposefulness, access to healthcare, and a strong sense of belonging (DVA/DOD, 2013).

Protective Factors

Within a social support system such as the military, protective factors include:

- Strong interpersonal bonds

- Community support

- Employment

- Intact marriage

- Child-rearing responsibilities

- Responsibilities or duties to others

- A reasonably safe and stable environment

Personal traits that are protective factors include:

- Help-seeking

- Good impulse control

- Good skills in problem solving, coping, and conflict resolution

- Sense of belonging, sense of identity, and good self-esteem

- Cultural, spiritual, and religious beliefs about the meaning and value of life

- Optimistic outlook—identification of future goals

- Constructive use of leisure time (enjoyable activities)

- Resilience

Access to healthcare is also a protective factor and includes:

- Medical support

- Mental health care

- Clinical care for substance use disorders

- Participating in treatment

- A sense of the importance of health and wellness (VA/DoD, 2013)

A study published in 2015 looked at changes in suicide mortality of veterans and non-veterans by gender and history of VHA service use. It found that suicides among women veterans increased by 40% from 2000 to 2010, compared to a 13% increase in women non-veterans. The study also showed that among women veterans, those who use VHA care have suicide rates as much as 75% lower than those who do not. Male veterans also saw reduction in suicide rates, about 20%, for those who used VHA services (Hoffmire et al., 2015).

Risk Factors

Suicide prevention is a serious issue for service members and their loved ones. Stress that never seems to let up can affect anyone, and some service members may be at greater risk for suicide than others. Risk factors may include:

- Being a young, unmarried male of low rank

- A recent return from deployment, especially when experiencing health problems

- Adverse deployment experience

- Lack of advancement or reduction in rank

- A sense of a loss of honor or a perceived sense of injustice or betrayal

- Heavy drinking or other substance use problems

- Disciplinary actions

- Mental health problems

- Career-threatening change in fitness for duty

- Command/leadership stress, isolation from unit

- Transferring duty station

- Deployment to a combat theater (WSDOH, 2016)

Source: Defense Suicide Prevention Office.

National Guard members and reservists are of special concern because they often live in areas with limited access to healthcare services. Knowing when a person is at risk and recognizing the warning signs can help you take action to possibly prevent a suicide and make sure the person gets help.

Suicide rates are higher in the Army than in other branches. A 2010 offering, Health Promotion, Risk Reduction, Suicide Prevention Report, suggested potential causes for these higher rates:

- Lapses in garrison leadership supervision and control

- Lowering recruitment standards through increased use of waivers

- Admittance of recruits who engage in high-risk behavior (WSDOH, 2016)

Veterans: Intervention Strategies

Training on resilience, stress, and preparation have done little to curb rising suicide rates. The emphasis must go deeper to explore issues such as regulation, integration, belongingness, burden, and habituation and allow service members to reflect meaningfully upon their military experience (WSDOH, 2016).

The United States Air Force Suicide Prevention Program includes 11 policy and education initiatives that are designed to change the culture surrounding suicide. The program uses leaders as role models and agents of change, establishes expectations for behavior related to awareness of suicide risk, develops population skills and knowledge (education and training), and investigates every suicide. The program represents a fundamental shift from viewing suicide and mental illness solely as medical problems and instead sees them as larger service-wide problems impacting the whole community (Stone et al., 2017).

The program has been associated with a 33% relative risk reduction in suicide. It was also associated with relative risk reductions in related outcomes, including moderate and severe family violence, homicide, and accidental death. An assessment comparing suicide rates before and after the launch of the program found significantly lower rates of suicide after the program was launched. These effects were sustained over time, except in 2004, during which there was less rigorous implementation of program components than in the other years (Stone et al., 2017).

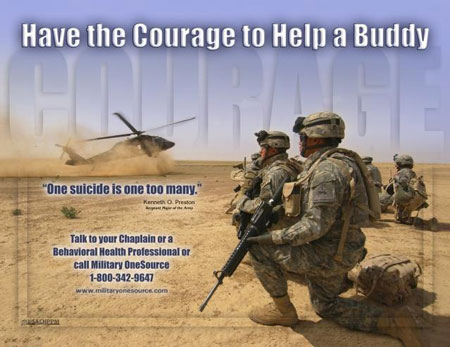

Source: U.S. Army suicide prevention poster. Source: United States Army.

Health-Promoting Behaviors

Good health is critical to military and family readiness, allowing service members to perform their responsibilities at work and at home to the best of their abilities. Source: Military OneSource.

Several health-promoting behaviors, including physical activity, stress management, and interpersonal relationships, have been demonstrated to decrease suicidal ideation. Those who engage in physical activity or participate in sports are at lower risk for suicidal ideation than those who do not. In the realm of spiritual growth, individuals who feel they have a purpose in life reported lower suicidal ideation than those who did not. In terms of social relationships, there is a significant body of literature identifying social support as a protective factor for suicidal ideation (DeBeer et al., 2016).

Practicing good nutrition boosts personal performance. Source: Military OneSource.

Of particular interest, researchers have found that suicide attempters tended to have diets lower in dietary fiber and polyunsaturated fat compared to individuals who had no history of suicide attempts. Further, men and women who had prior suicide attempts were more likely to have insufficient intake of vegetables and fruits respectively compared to non-attempters (DeBeer et al., 2016).

Addressing PTSD

There is evidence to support a similar relationship between health-promoting behaviors and PTSD symptoms. Adults who participated in an exercise intervention showed decreased levels of PTSD symptoms compared to baseline, and this reduction lasted after the intervention was completed (DeBeer et al., 2016).

Veterans with PTSD who felt they have purpose and meaning in life have better outcomes than those who do not. Social support is associated with lower PTSD symptom severity in trauma-exposed individuals. Disrupted sleep is a core symptom of PTSD, and research demonstrates that cognitive-behavioral treatments that reduce insomnia and nightmares can reduce other symptoms of PTSD (DeBeer et al., 2016).

Veterans and PTSD: Challenging the Misconceptions (2:13)

https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov

Addressing Depression

Major depressive disorder, which is highly comorbid with PTSD, independently increases risk for suicidal ideation and attempts. Thus, identifying modifiable factors that could reduce the association between PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation is a high research priority (DeBeer et al., 2016).

The veterans Affairs Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) projectuses a depression care liaison to link primary care and mental health services. The depression care liaison assesses and educates patients and follows up with both patients and providers to optimize treatment between primary care visits. This collaborative care supports mental health services by bringing mental health care to the primary care setting, where most patients are first detected and subsequently treated for many mental health conditions. An evaluation of TIDES found significant decreases in depression severity scores among 70% of primary care patients. TIDES patients also demonstrated 85% and 95% compliance with medication and followup visits, respectively (Stone et al., 2017).

Defense Suicide Prevention Office

The Defense Suicide Prevention Office (DSPO) provides advocacy, program oversight, and policy for Department of Defense suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention efforts to reduce suicidal behaviors in Service members, civilians, and their families.

The Defense Suicide Prevention Office (DSPO) is collaborating with the Star Behavioral Health Providers (SBHP)* program on a pilot project in Indiana and California to offer military cultural training to community healthcare providers and other support personnel. The goal of the program is to improve military cultural competency through education and outreach so civilian providers can better support Service members in every county in the two states.

Together with the Purdue University Military Family Research Institute, the UCLA Nathanson Family Resilience Center, and the Center for Deployment Psychology, DSPO is gathering insights into the challenges these individuals face when seeking care, especially in rural and remote locations, and how to better address these gaps in services in order to prevent suicide. Upon completion of a successful pilot program, SBHP and DSPO plan on expanding efforts into other participating states (DSPO, 2017).

*Star Behavioral Health Providers: a resource for veterans, Service members, and their families to locate behavioral health professionals with specialized training for understanding and treating members of the military community. SBHP has a registry at www.starproviders.org that informs Service members, particularly National Guard and Reservists and their families, about providers available in their communities. Seven States—California, Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, New York, and South Carolina—currently offer SBHP programs (DSPO, 2017).

Veterans Crisis Line

The Veterans Crisis Line encourages veterans and their families and friends to call when a veteran is experiencing a crisis. Those who know a veteran may be the first to recognize emotional distress and reach out for support when issues reach a crisis point—and well before a veteran is at risk of suicide. The Veterans Crisis Line has specially trained responders who can help veterans of all ages and circumstances. Some of the responders are veterans themselves and they understand what veterans and their families and friends have been through and the challenges they face (DVA, nd).

Since its launch in 2007, the Veterans Crisis Line has answered nearly 2.8 million calls and initiated the dispatch of emergency services to callers in crisis nearly 74,000 times. The Veterans Crisis Line anonymous online chat service, added in 2009, has been used more than 332,000 times. In November 2011, the Veterans Crisis Line introduced a text-messaging service to provide another way for veterans to connect with confidential, round-the-clock support, and since then has responded to more than 67,000 texts (DVA, nd).

Source: VeteransCrisisLine.net