*This course has been retired. Please click here for new course, About Suicide: Washington State, 6 units.

The potential for suicide exists when there is no longer a sense of belonging, when a person feels he is a burden, and when there is habituation to self-injury. This can lead a person to gradually overcome the desire for self-preservation and lower resistance to self-injury through rehearsal or observed self-harm actions (WSDOH, 2016).

Imminent harm is a situation in which a person's risk status is believed to indicate actions that could lead to his or her suicide. Healthcare providers working in EDs, acute care, and medical offices must be able to identify, treat, and follow up with those at risk for harming themselves. Risk of imminent harm is especially elevated during the days and weeks following hospitalization for a suicide attempt, especially for people diagnosed with major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Followup and referral are critical components of effective care (WSDOH, 2016).

Recognizing Self-Injurious Behaviors

Self-injurious behaviors and intentions are deliberate acts done with the knowledge that they can or will result in some degree of physical or psychological injury. Self-injurious behavior involves direct and intentional self-injury that causes tissue damage, injury to oneself, or injury to health. It also includes suicide attempts (Xin et al., 2016).

Non-suicidal self-harm is included in some suicide risk measures, such as the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview. However, recent research found that including nonsuicidal self-harm did not provide additional predictive ability to a model including suicidal cognition and behaviors. Overall, there is considerable evidence that past suicidal plans and attempts should be considered for evaluation of current and future risk, but other behaviors, such as nonsuicidal self-harm and communications, may not be valid factors for many individuals (Harris et al., 2015).

Assessing Intent

Intentions are self-instructions that guide engagement in a behavior or lead to an outcome. Measures of intention provide a numerical score that reflect how hard a person is willing to try or the likelihood a person will perform or try to perform a particular behavior. Several theories incorporate intentions as a primary determinant of behavior. These theories argue that intention is an important underlying driver of behavior and that other influencing factors are either mediated by intention or serve as moderators (Williams, 2016).

The ability to perceive intentionality appears to be automatic and by adulthood most individuals share a common understanding of the concept of intentionality. Given the importance of inferring the intentions of others, it is not surprising that most adults are keenly attuned to intentionality cues. The fast and automatic operation of these cognitive processes allows us to make inferences quickly about the mental states of those around us (Brotherton & French, 2015).

A great deal of evidence demonstrates that suicidal behaviors (plans and attempts) can be predictive of suicide. Including an individual’s intent to die in a risk assessment improves the validity of past suicidal behaviors as indicators of current and future risk. Many instruments, such as the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised and the Suicide Intent Scale, include items on communication of suicide ideation and behavior (Harris et al., 2015). However, measures of intention that only capture a person’s general desire to perform a behavior are significantly less robust predictors of subsequent behavior than measures of intention that assess the intensity and level of effort the person is prepared to exert to perform the behavior (Williams, 2016).

Beck Suicide Intention Scale

The Beck Suicide Intention Scale (SIS) examines subjective and objective aspects of the suicide attempt, the circumstances at the time of the attempt, and the patient’s thoughts and feelings during the attempt. It is based on a clinical interview using an instrument with 15 items referring to the patient’s precautions and beliefs of the act. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 2, with a possible total score of 30 indicating the highest intention of suicide and a wish to die.

The SIS questionnaire covers precautions, planning, communication, and expectations regarding medication load, the degree of planning, and wish to die or live. It is divided into two sections: the first eight items constitute the “circumstances” section (part 1) and are concerned with the objective circumstances of the act of self-harm; the remaining seven items, the “self-report” section (part 2), are based on the patients’ own reconstruction of their feelings and thoughts at the time of the act.

Source: Grimholt et al., 2017.

A person’s intent may be inferred from how they describe a “wish to live” or a “wish to die.” These terms have proven useful in assessing suicide ideation and behavior, and are included in Beck’s Scale of Suicidal Ideation and the Suicide Status Form. Overall, there is strong evidence that suicidal affects can be valid indicators of current and future risk (Harris et al., 2015).

Paradoxically, an examination of U.S. suicide attempters indicated that prior verbalization of suicidality had little relationship with a “wish to die” during the attempt. A large study of French university students found higher-risk suicide attempts, included less communication of suicidality, while a psychological autopsy study of 200 Chinese suicide victims revealed about 60% had not communicated their intentions, in any way, prior to death (Harris et al., 2015).

Self-Injurious Behaviors in Young People

Nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior such as cutting, burning, hitting oneself, scratching oneself to the point of bleeding, or interfering with healing is a relatively frequent behavior in young people. The concern is that it these behaviors can become chronic and evolve into other forms of self-injurious behavior, such as suicide attempts. Because nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior and suicidal behavior often occur together, it is important to consider the nature of the link between these two types of behavior. Some specialists see nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior as a way to regulate negative emotions, while others argue that it is a factor in the emergence of suicidal ideation and attempts (Grandclerc et al., 2016).

Stigma

There is a misconception—even among some healthcare providers—that individuals who self-harm choose to suffer. This creates stigma regarding self-harm. Similar experiences with stigma have been reported by people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. General psychiatric admission is of uncertain therapeutic value for self-harming and suicidal individuals and may even be harmful for those with borderline personality disorder, especially if admissions are lengthy and unstructured. Although often lacking, specialized services are essential—particularly in situations of unique vulnerability, such as suicidal crises. When the risks of suicide and severe self-harm are acute, it is essential that services are offered in a compassionate manner that honors the human dignity of the person who is suffering (Liljedahl et al., 2017).

About Self-Harm—A Nurse Practitioner’s Perspective

Nonsuicidal self-injury often involves people with borderline personality disorders; self-harm is an antidote to psychological numbing. This doesn’t let providers off the hook in terms of assessing safety and lethality but this sort of situation requires a different kind of assessment.

A clinician must decide what direction the self-harm is heading—from superficial and visible self-harm to deeper and less visible self-injury. People with certain types of mental illness are more likely to be associated with escalating self-harm, with an ever-greater likelihood of a completed suicide.

Objects, Substances, and Actions Common in Suicide Attempts

Lethal means are things people might use in a suicide attempt that are likely to result in death (eg, firearms, medications, poisons). This can include objects such as firearms, substances such as alcohol or drugs, and actions such as jumping from a building.

In Washington State, most people who die by suicide use a firearm, suffocation (frequently hanging), or poisoning (drug or medication overdose or swallowing harmful substances). About half of suicides in Washington involve firearms. Less common, but still of concern, are suicide deaths by jumping/falling or cutting. Limiting or reducing an at-risk person’s access to lethal means effectively prevents suicides (WSDOH, 2016).

Possible determinants for different methods of suicide such as age, gender, suicide intent, mental health status, and timing have been identified by researchers. A study conducted in New York found that although the most common method of suicide was firearms, fall from height was a common method by elder residents. A study in Japan found that men were more likely to use lethal methods than women, with similar findings in European populations. The method used in an unsuccessful suicide attempt may predict later completed suicide, suggesting the study of suicide methods may be of significance in suicide prevention (Sun and Jia, 2014).

Suicide methods can be divided into two main categories: violent methods, which include firearm or shotgun, hanging, cutting and piercing with sharp objects, jumping from high places, and getting run over by train or other vehicles. Nonviolent methods include ingestion of pesticides, poison by gases, suffocation, and overdose. Access, availability, social acceptability of certain suicide methods and some location-specific factors such as access to firearms or tall buildings are important factors to consider (Sun and Jia, 2014).

Objects Commonly Used in Suicide Attempts

Household gun ownership rates at the state level are a significant positive predictor of both homicides and suicides. A substantial proportion of Americans—over 50%, in some states—live in households with guns and may not need to purchase a new firearm to carry out a violent act (Swanson et al., 2015).

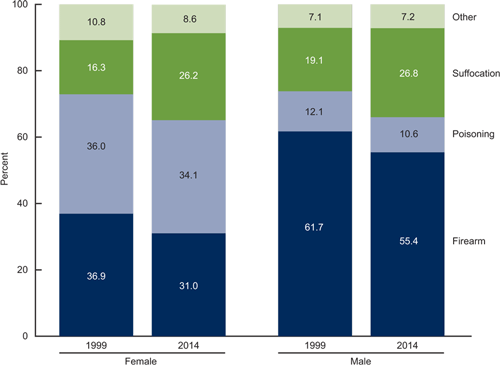

More than half of male suicides (55.4%) in 2014 were firearm-related (NCHS, 2016). Although individuals who own firearms are not more likely than others to have a mental disorder or to have attempted suicide, the risk of a death is higher among this population because individuals who attempt suicide by using firearms are more likely to die in their attempts than those who use less lethal methods (HHS, 2012).

Among veterans, the most common means for suicide is firearms, with approximately 41% of female and 68% of male suicide deaths resulting from a firearm in 2014. The use of firearms as the mechanism for suicide death decreased among civilians from 2001 to 2014, but remained stable among veterans. These results strongly suggest that firearms safety initiatives are likely an important component of an effective suicide prevention strategy for male and female veterans (USDVA, 2016b).

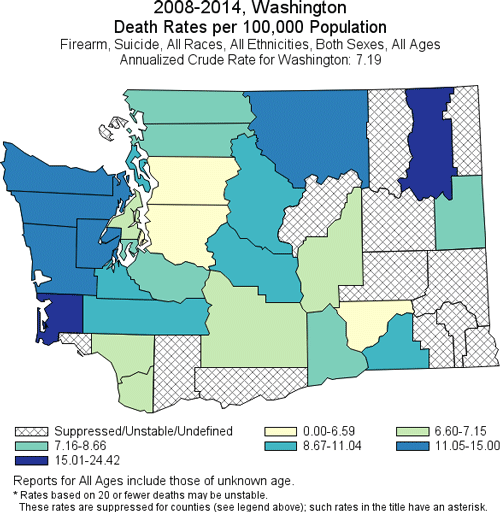

Suicide Deaths in Washington by Firearm (2008–2014)

Produced by: the Statistics, Programming & Economics Branch, National Center for Injury Prevention & Control, CDC.

Data Sources: NCES National Vital Statistics System for numbers of deaths; US Census Bureau for population estimates.

Substances Commonly Used in Suicide Attempts

Poisoning (predominantly drug overdose) is the leading mechanism for suicide death among females and the third leading mechanism for males aged 35 to 64. Despite this, current suicide prevention strategies are primarily targeted towards teenagers, young adults, and elders. This increase in suicide attempts (and suicide death) among middle-aged adults underscores the importance of understanding risk factors for suicide in this age group to ensure that targeted preventive interventions are implemented (Tesfazion, 2014).

Nearly all drug-related ED visits involving suicide attempts among middle-aged adults involve prescription drugs and over-the-counter medications. About half of visits involved anti-anxiety and insomnia medications, 29% involved pain relievers, and 22% involved antidepressants. Within this age group, more than a third of all drug-related ED visits involving a suicide attempt also involved alcohol, and 11% involved illicit drugs (Tesfazion, 2014).

Among female veterans, poison is the second-most common means of suicide—32% who die by suicide use poison. Among male suicide victims, suffocation is the second-most common cause of death (17%, 2014) (USDVA, 2016b).

Inert gas asphyxiations such as those from helium have also increased in the United States. The increasing familiarity and lethality with helium is partly the reason for the rise in suicide by helium. There are a many internet websites that provide details on helium asphyxiations. Helium suicides have also been publicized as simple and painless. More formal recommendations regarding suicides with inert gas asphyxiations such as helium need to be developed. Besides physically restricting access to helium, one way to curb helium suicides would be to have professionals assess if at-risk patients have read materials on helium suicides (Hassamal et al., 2015).

Actions Common in Suicide Attempts

The most frequent “other” suicide methods in 2014 for females were falls (2.8%) and drowning (1.4%). For males, the most frequent “other” methods were falls (2.2%) and cutting or piercing (1.9%) (NCHS, 2016). Although falling from buildings or bridges is a relatively small percentage of suicide attempts, it is a particularly lethal method of suicide (Hemmer et al., 2017). For both females and males, about 25% of suicides in 2014 were attributable to suffocation (includes hanging, strangulation, and suffocation), an increase over previous years (NCHS, 2016).

In the United States, from 2000 to 2010, asphyxiations increased by 52%. The high prevalence of asphyxiations can be attributed to easy accessibility of rope and widespread availability of other means for hanging. Currently, there are no specific formal proposals on how to reduce asphyxiation suicides. The easy availability of ligature materials makes prevention of hanging suicides a difficult task. Research indicates that those who attempted suicide by hanging viewed it as a quick, simple, and painless death. Therefore, one way to reduce hanging suicides would be to challenge perceptions of hanging as a quick, simple, and painless suicide method (Hassamal et al., 2015).

Number of Suicide Deaths by Method (2015) | |

|---|---|

Suicide Method | Number of Deaths (2015) |

Total | 44,193 |

Firearm | 22,018 |

Suffocation | 11,855 |

Poisoning | 6,816 |

Other | 3,504 |

Suicide Deaths, by Method and Sex: United States, 1999 and 2014

Source: NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

Talking About Lethal Means

Professionals who provide healthcare services to patients at risk for suicide are in a unique position to ask about lethal means and work with these individuals and their support networks to reduce access. Providers can educate patients and families about safe firearm storage and access, as well as the appropriate storage of alcoholic beverages, prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, and poisons. However, many may fail to do so, or do so only when a patient is identified as being at a very high risk for suicide (HHS, 2012).

Individuals experiencing significant distress or who have a recent history of suicidal behavior should not have easy access to means that may be used in a suicide attempt, including firearms, other weapons, medications, illicit drugs, chemicals used in the household, other poisons, or materials used for hanging or suffocation.

Providers should talk to patients and caregivers about reducing the stock of medicine in the medicine cabinet to a nonlethal quantity, and locking medicines that are commonly abused (eg, prescription painkillers and benzodiazepines). This approach can be useful in helping to prevent suicide, as well as unintentional overdoses and substance abuse (HHS, 2012).

Talking about Lethal Means—A Nurse Practitioner’s Guidance

Once you have identified that your patient is at risk for self-harm, try to identify any lethal means that your patient might be able to access once he or she leaves your office. Ask direct questions: “While you’re in this dangerous period, may I call your partner or family member and ask them to remove the guns or poisons from the house?”

Ask permission and show concern in a non-judgmental manner—this is more likely to elicit information from your patient. You can continue by saying “I want to let you know that I appreciate and am honored that you’ve shared your thoughts with me. I’m just concerned that you may go again to a place of despair when you leave and I’m thinking of your safety.”

Try to establish and maintain trust with your patient—if you think the person is at risk, there is no reason to cover your concern or to lie.

Restricting Access to Lethal Means

Means restriction is the techniques, policies, and procedures designed to reduce access or availability to means and methods of deliberate self-harm. Among suicide prevention interventions, reducing access to highly lethal means of suicide has a strong evidence base and is now considered a key strategy to reduce suicide death rates (Betz et al., 2016).

Reducing access to firearms is particularly important, since firearm suicide attempts have a high case-fatality rate and firearms account for 51% of all suicide deaths in the United States. Patients with firearm access at home might be considered at particularly high risk for discharge to their home, given that firearm access is a risk factor for suicide, the actual act of a suicide attempt often occurs within only minutes of the decision to attempt, and approximately 90% of firearm suicide attempts are fatal (compared to as few as 2% of medication overdoses) (Betz et al., 2016).

While access to firearms and other lethal means in a patient with suicidal ideation and behavior by itself does not mandate psychiatric admission, restricting access to firearms is a key component of home safety planning that should be addressed with all patients being discharged. Safe storage of firearms and other lethal means has been associated with less risk for suicide among adults and youth, and lethal means counseling in EDs might affect storage behavior (Betz et al., 2016).

Reducing access to potentially toxic medications is also important but can be a challenge, given that many of the medications used to treat mental illness can be toxic in an overdose. In one sample, 60% of patients reported currently taking at least one medication for an emotional or psychological problem, and medication overdose was the suicide method most commonly reported as having been considered (Betz et al., 2016).

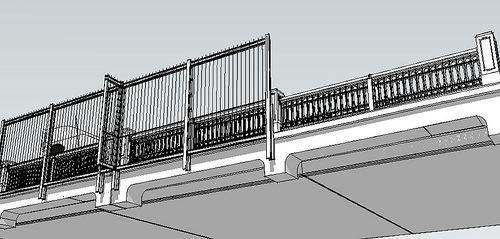

Access to other lethal means of suicide—such as sharp objects or supplies for hanging—is also difficult to control given their widespread availability for other purposes. Installing bridge barriers or otherwise restricting access to popular jump sites may prevent deaths, depending on specific local conditions.

Intervening at Suicide Hotspots

Suicide hotspots, or places where suicides may take place relatively easily, include tall structures such as bridges, cliffs, balconies, and rooftops; railway tracks; and isolated locations such as parks. Efforts to prevent suicide at these locations include erecting barriers or limiting access to prevent jumping, and installing signs and telephones to encourage individuals who are considering suicide to seek help (Stone et al., 2017).

A meta-analysis examining the impact of suicide hotspot interventions implemented in combination or in isolation, both in the United States and abroad, found associated reduced rates of suicide. For example, after erecting a barrier on the Jacques-Cartier Bridge in Canada, the suicide rate for jumping from the bridge decreased from about 10 suicide deaths per year to about 3 deaths per year. Moreover, the reduction in suicides by jumping was sustained even when all bridges and nearby jumping sites were considered, suggesting little to no displacement of suicides to other jumping sites. Further evidence for the effectiveness of bridge barriers was demonstrated by a study examining the impact of the removal of safety barriers from the Grafton Bridge in Auckland, New Zealand (see box) (Stone et al., 2017).

Unintended Consequences—The Grafton Bridge, Auckland, New Zealand

Safety barriers to prevent suicide by jumping were removed from Grafton Bridge in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1996 after having been in place for 60 years. The barriers were reinstalled in 2003. A study compared mortality data for suicide deaths for three time periods:

- 1991–1995 (old barrier in place)

- 1997–2002 (no barriers in place)

- 2003–2006 (new barriers in place)

Removal of barriers was followed by a fivefold increase in the number and rate of suicides from the bridge. Since the reinstallation of barriers, there have been no suicides from the bridge. This natural experiment shows that safety barriers are effective in preventing suicide: their removal increases suicides; their reinstatement prevents suicides.

Source: Harvard School of Public Health, 2017.

Public jump sites are well-suited for suicide prevention, given that a great number of suicides are often limited to a few structures. At these hotspots, substantial suicide preventive effects can be achieved by a few prevention efforts. Most interventions for suicide prevention on bridges are of a structural nature (Hemmer et al., 2017).

Did You Know. . .

The Aurora Bridge in Seattle had the second highest suicide death toll in the United States (behind the Golden Gate Bridge). In 2006 emergency call boxes and signs with a suicide hotline number were installed on the bridge. Suicides continued to occur at an average of about five per year until a fence was installed in 2011. In the 18 months afterward, only one suicide occurred (Draper, 2017).

Outside view visualization of the Aurora Bridge Fence suicide barrier in Seattle prior to its construction in 2010. Source: Washington State Department of Transportation.

Some interventions to prevent jumps from hotspots or other methods of suicide are not feasible for bridges. Although blocking access roads to hotspots have been shown to deter suicide jumps, this is not a viable measure for most bridges. There is evidence that the number of suicides by carbon monoxide poisoning in public parking lots has been reduced by installing aid signs. However, no studies exist that evaluate the effectiveness of aid signs as the sole intervention when used on bridges or other jumping sites, although they are widely installed (Hemmer et al., 2017).

Some research has shown that, if in addition to aid signs, emergency helpline phones are directly available on bridges, the phones are used on a regular basis. Other research has shown that, in combination with increased police presence, emergency helplines led to a decrease in the number of suicides at the Sunshine Skyway Bridge in Florida (Hemmer et al., 2017).

Safe Storage Practices

San Francisco VA Health Care System providers are helping prevent Veteran suicide through lethal means safety. Source: U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs.

Safe storage of medications, firearms, and other household products can reduce the risk for suicide by separating vulnerable individuals from easy access to lethal means. Such practices may include education and counseling around storing firearms locked in a secure place (eg, a gun safe, lock box), unloaded and separate from the ammunition; and keeping medicines in a locked cabinet or other secure location away from people who may be at risk or who have made prior attempts (Stone et al., 2017).

In a case-control study of firearm-related events identified from 37 counties in Washington, Oregon, and Missouri, and from five trauma centers, researchers found that storing firearms unloaded, separate from ammunition, in a locked place or secured with a safety device was protective of suicide attempts among adolescents. Further, a recent systematic review of clinic and community-based education and counseling interventions suggested that the provision of safety devices significantly increased safe firearm storage practices compared to counseling alone or compared to the provision of economic incentives to acquire safety devices on one’s own (Stone et al., 2017).

Locking Devices for Handguns and Other Firearms

Source: Kingcounty.gov.

Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (ED CALM)

The Emergency Department Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (ED CALM) has trained psychiatric emergency clinicians in a large children’s hospital to provide lethal means counseling and safe storage boxes to parents of patients under age 18 receiving care for suicidal behavior. In a pre/post quality improvement project, researchers found that, at post test 76% reported that all medications in the home were locked up as compared to fewer than 10% at the time of the initial ED visit. Among parents who indicated the presence of guns in the home at pre test (67%), all (100%) reported guns were currently locked up at post test (Stone et al., 2017).

Policy-Based Strategies

Policy-based strategies that restrict access to lethal means have led to positive results. For example, limiting access to suicide methods such as carbon monoxide has resulted in decreases in suicide by carbon monoxide. Restriction of other suicide methods has also shown positive results. The implementation of enhanced restrictions to purchase firearms in the District of Columbia led to reductions in firearm-related suicides (Hassamal et al., 2015).

Implementation of means restriction is broad and can include (1) complete removal of a lethal method, (2) reducing the toxicity of a lethal method, for example, reducing carbon monoxide content emissions from vehicles, (3) interfering with physical access, for example, using gun locks, (4) enhancing safety, for example, encouraging at-risk families to remove lethal suicide means from the home, or (5) reducing the appeal of a more lethal method, for example, changing the perception of hanging as a quick and painless death. The majority of suicide attempts are transient and the time between contemplating suicide and the attempt is less than 5 minutes for many attempters. The method depends on what is readily available (Hassamal et al., 2015).

Although this goal focuses on reducing access to lethal means among individuals at risk, evidence for means restriction has come from situations in which a universal approach was applied to the entire population. For example, the detoxification of domestic gas in the United Kingdom and discontinuation of highly toxic pesticides in Sri Lanka were universal measures associated with 30% and 50% reductions in suicide, respectively (HHS, 2012).