The first time I heard the term “lethal means,” I had no idea what it meant. Now I realize how important it is to understand the various ways people attempt suicide.

Nurse Practitioner, California

Lethal means are objects, substances or actions that might be used in a suicide attempt. This can include firearms, poisons, alcohol or drugs, and actions such as jumping from a bridge or building. Limiting access to lethal means (lethal means safety) has been found to be one of the most effective approaches to reducing suicide (DSPO, 2020).

Throughout the U.S., most people who die by suicide use a firearm. In Washington, about half of suicides involve firearms. Less common, but still of concern, are suicide deaths by jumping, falling or cutting (WSDOH, 2016).

Age, gender, intent, mental health status, and timing play a role in the method used. A study conducted in New York found that although the most common method of suicide was firearms, fall from height was a common method by elder residents. A study in Japan found that men were more likely to use lethal methods than women, with similar findings in European populations. The method used in an unsuccessful suicide attempt may predict later completed suicide (Sun and Jia, 2014).

Suicide methods can be divided into violent or nonviolent methods. Violent methods can include firearms, hanging, cutting or piercing with sharp objects, jumping from high places, and getting run over by train or other vehicles. Nonviolent methods can include ingestion of pesticides, poison by gases, suffocation, and overdose. Access, availability, social acceptability of certain methods and some location-specific factors such as access to firearms or tall buildings are important factors to consider (Sun and Jia, 2014).

6.1 Objects, Substances, and Actions Common in Suicide Attempts

Household gun ownership rates at the state level are a significant positive predictor of both homicides and suicides. A substantial proportion of Americans—over 50%, in some states—live in households with guns and may not need to purchase a new firearm to carry out a violent act (Swanson et al., 2015). In 2019, 50% of the more than 47,000 suicides in the U.S. were by firearm and 60% of all firearm deaths were attributed to suicide (Kivisto, 2022).

Although individuals who own firearms are not more likely than others to have a mental disorder or to have attempted suicide, the risk of a death is higher among this population because individuals who attempt suicide by using firearms are more likely to die in their attempts than those who use less lethal methods.

Among non-veterans overall, there were increases from 2001 to 2019 in the percentage of suicides involving suffocation and “other means” and decreases in the percentage involving firearms and poisoning. Among veterans, there were increases in the percentage involving firearms and suffocation and decreases for those involving poisoning and other means (USDVA, 2021, September).

Firearms accounted for over 70% of male veteran suicides in 2019 and nearly half of female veteran suicides in 2019. The proportion of firearm-related veteran suicide deaths increased in 2019 compared to 2001 (USDVA, 2021, September).

Overdose deaths in the U.S. involving prescription opioids increased in 2020, reversing a two-year downward trend from a peak in 2017, and that one quarter of all opioid overdose deaths involved prescription opioids. Despite a decline in the overall opioid prescribing rate in the U.S. over the last 8 years, prescribing rates continue to remain very high in certain areas of the country (Luo et al., 2022).

One of the largest and most comprehensive investigations of the association between prescription opioids and suicide to date found a significant increase in the risk of suicidal behavior among patients with frequent opioid use, particularly at higher doses. Patients prescribed opioid medications for at least 6 months in the past year had approximately five to seven times the risk of attempted suicide compared to those not prescribed opioid medications. Coupled with the effects of psychiatric conditions such as depression/bipolar disorders and psychosis, frequent use of moderate to high strength prescription opioids placed such patients at substantially elevated risk of suicidal behavior (Luo et al., 2022).

Current suicide prevention strategies are primarily targeted towards teenagers, young adults, and elders despite the fact that poisoning (predominantly drug overdose) is the leading mechanism for suicide death among middle-aged females and the third leading mechanism for middle-aged males. This increase in suicide attempts (and suicide death) among middle-aged adults underscores the importance of understanding risk factors for suicide in this age group to ensure that targeted preventive interventions are implemented (Tesfazion, 2014).

Nearly all drug-related ED visits involving suicide attempts among middle-aged adults involve prescription drugs and over-the-counter medications. About half of visits involved anti-anxiety and insomnia medications, 29% involved pain relievers, and 22% involved antidepressants. Within this age group, more than a third of all drug-related ED visits involving a suicide attempt also involved alcohol, and 11% involved illicit drugs (Tesfazion, 2014).

Inert gas asphyxiations such as those from helium have also increased in the United States. The increasing familiarity and lethality with helium is partly the reason for the rise in suicide by helium. There are many internet websites that provide details on helium asphyxiations. Helium suicides have also been publicized as simple and painless. More formal recommendations regarding suicides with inert gas asphyxiations such as helium need to be developed. Besides physically restricting access to helium, one way to curb helium suicides would be to have professionals assess if at-risk patients have read materials on helium suicides (Hassamal et al., 2015).

The most frequent “other” suicide methods are falls, drowning, cutting or piercing, and suffocation. Although falling from buildings or bridges is a relatively small percentage of suicide attempts, it is a particularly lethal method of suicide (Hemmer et al., 2017). For both females and males, suicide by suffocation or asphyxiation has increased significantly since 2000, especially in rural areas (NCHS, 2020, August 19).

The high prevalence of asphyxiations can be attributed to easy accessibility of rope and widespread availability of other means for hanging. Currently, there are no specific formal proposals on how to reduce asphyxiation suicides. The easy availability of ligature materials makes prevention of hanging suicides a difficult task. Research indicates that those who attempted suicide by hanging viewed it as a quick, simple, and painless death. Therefore, one way to reduce hanging suicides would be to challenge perceptions of hanging as a quick, simple, and painless suicide method (Hassamal et al., 2015).

Number of Suicide Deaths by Method (2022) | |

|---|---|

Suicide Method | Number of Deaths (2022) |

All Methods | 45,979 |

Firearm | 24,292 |

Suffocation | 12,495 |

Poisoning | 5,528 |

6.2 Restricting Access to Lethal Means

Means restrictions are the techniques, policies, and procedures designed to reduce access or availability to means and methods of deliberate self-harm. Among suicide prevention interventions, reducing access to highly lethal means is now considered a key strategy to reduce suicide death rates (Betz et al., 2016).

Various strategies to reduce access to lethal means have been developed and implemented in several countries. Means restriction is considered a key component in a comprehensive suicide prevention strategy and has been shown to be effective in reducing suicide rates (DVA/DOD, 2019).

Means safety counseling (MSC)—also referred to as “lethal means counseling”—approaches have been developed in an effort to reduce deaths by firearms and other means. Examples of MSC recommendations include storing firearms in locked cabinets, using gunlocks, giving keys to these locks to family, caregivers, or friends, temporarily transferring firearms to someone legally authorized to receive them, removing firing pins, or otherwise disabling the weapon (DVA/DOD, 2019).

Restricting access to firearms is a key part of home safety planning that should be addressed with a patient is being discharged. Safe storage of firearms and other lethal means has been associated with less risk for suicide among adults and youth (Betz et al., 2016).

Reducing access to potentially toxic medications can be a challenge, given that many of the medications used to treat mental illness can be toxic in an overdose. In one sample, 60% of patients reported taking at least one medication for an emotional or psychological problem, and medication overdose was the suicide method most commonly reported as having been considered (Betz et al., 2016).

Access to other lethal means of suicide—such as sharp objects or supplies for hanging—is also difficult to control given their widespread availability for other purposes. Installing bridge barriers or otherwise restricting access to popular jump sites may prevent deaths, depending on specific local conditions.

People tend not to substitute a different method when a highly lethal method is unavailable or difficult to access. Increasing the time interval between deciding to act and the suicide attempt by making it more difficult to access lethal means, can be lifesaving (CDC, 2022).

A suicide attempt using a gun leads to death in 85% to 90% of cases; an attempt by medication overdose or a sharp instrument, leads to death about 1 to 2% of the time. It is important to understand that most people who attempt suicide once, and survive, never attempt again. Putting time, distance, and other barriers between a person at risk and the most lethal means can make the difference between life and death (WSDOH, 2016).

6.2.1 Intervening at Suicide Hotspots

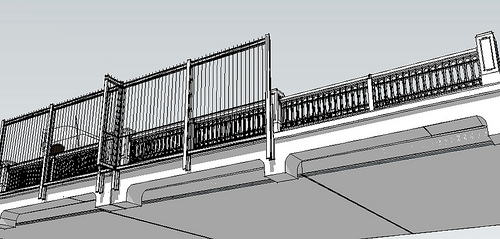

Suicide hotspots include tall structures such as bridges, cliffs, balconies, rooftops, railway tracks, and isolated locations such as parks. Efforts to prevent suicide at these locations include erecting barriers or limiting access to prevent jumping and installing signs and telephones to encourage individuals who are considering suicide to seek help (CDC, 2022).

An examination of the impact of suicide hotspot interventions implemented both in the U.S. and abroad, found associated reduced rates of suicide. For example, after erecting a barrier on the Jacques-Cartier Bridge in Canada, the suicide rate for jumping from the bridge decreased from about 10 suicide deaths per year to about 3 deaths per year. The reduction in suicides by jumping was sustained even when all bridges and nearby jumping sites were considered, suggesting little to no displacement of suicides to other jumping sites. Further evidence for the effectiveness of bridge barriers was demonstrated by a study examining the impact of the removal of safety barriers from the Grafton Bridge in Auckland, New Zealand (see box) (CDC, 2022).

A great number of suicides are often limited to a few structures. At these hotspots, substantial suicide preventive effects can be achieved by a few prevention efforts. Most interventions for suicide prevention on bridges are of a structural nature (Hemmer et al., 2017).

An Australian study of looked at the cost effectiveness of installing barriers at 7 bridges and 19 cliff sites. Researchers found that the cost of installing barriers was both cost-effective and an effective strategy for suicide prevention. Barriers at bridge sites were associated with an 84% decrease in suicides, while a reduction in suicides was noted at several of the cliff sites (Bandara et al., 2022).

Unintended Consequences—The Grafton Bridge, Auckland, New Zealand

Safety barriers to prevent suicide by jumping were removed from Grafton Bridge in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1996 after having been in place for 60 years. The barriers were reinstalled in 2003. A study compared mortality data for suicide deaths for three time periods:

- 1991–1995 (old barrier in place)

- 1997–2002 (no barriers in place)

- 2003–2006 (new barriers in place)

Removal of barriers was followed by a fivefold increase in the number and rate of suicides from the bridge. Since the reinstallation of barriers, there have been no suicides from the bridge. This natural experiment shows that safety barriers are effective in preventing suicide: their removal increases suicides; their reinstatement prevents suicides.

Source: Harvard School of Public Health, 2017.

Did You Know. . .

The Aurora Bridge in Seattle had the second highest suicide death toll in the United States (behind the Golden Gate Bridge). In 2006 emergency call boxes and signs with a suicide hotline number were installed on the bridge. Suicides continued to occur at an average of about five per year until a fence was installed in 2011. In the 18 months afterward, only one suicide occurred (Draper, 2017).

Outside view visualization of the Aurora Bridge Fence suicide barrier in Seattle prior to its construction in 2010. Source: Washington State Department of Transportation.

Although blocking access roads to hotspots can deter suicide jumps, this is not a practical measure for most bridges. Although there is evidence that the number of suicides by carbon monoxide poisoning in public parking lots has been reduced by installing aid signs, no studies exist that evaluate the effectiveness of aid signs as the sole intervention when used on bridges or other jumping sites, although they are widely installed. However, when emergency helpline phones are directly available on bridges, they are used on a regular basis (Hemmer et al., 2017).

6.2.2 Promoting Safe Storage Practices

Safe storage of medications, firearms, and other household products can reduce the risk for suicide by separating vulnerable individuals from easy access to lethal means. Such practices may include education and counseling around storing firearms locked in a secure place (eg, a gun safe, lock box), unloaded and separate from the ammunition; and keeping medicines in a locked cabinet or other secure location away from people who may be at risk or who have made prior attempts (CDC, 2022).

In a case-control study of firearm-related events identified from 37 counties in Washington, Oregon, and Missouri, and from five trauma centers, researchers found that storing firearms unloaded, separate from ammunition, in a locked place or secured with a safety device was protective of suicide attempts among adolescents. Further, a recent systematic review of clinic and community-based education and counseling interventions suggested that the provision of safety devices significantly increased safe firearm storage practices compared to counseling alone or compared to the provision of economic incentives to acquire safety devices on one’s own (CDC, 2022).

Locking Devices for Handguns and Other Firearms

Source: Kingcounty.gov.

6.2.3 Policy-Based Strategies to Reduce Suicide

Like most public health problems, suicide is preventable. Progress continues to be made and evidence for numerous programs, practices, and policies exists. Just as suicide is not caused by a single factor, reductions in suicide will not be prevented by any single strategy or approach. Rather, suicide prevention is best achieved by a focus across the individual, relationship, family, community, and societal-levels and across all sectors, private and public (CDC, 2022).

National suicide prevention programs (NSPP) were initiated in the 1990s aiming to take a holistic approach to combat suicide. Prevention programs are designed to identify vulnerable groups, reduce stigma, improve the assessment and care of people with suicidal behavior, and improve surveillance and research. They also aim to raise awareness by improving public education (Lewitzka et al., 2019).

Policy-based strategies that restrict access to lethal means have led to positive results. There is strong evidence that restricting the availability of methods (e.g., firearms) can reduce suicides (Lewitzka et al., 2019). Limiting access to suicide methods such as carbon monoxide has resulted in decreases in suicide by carbon monoxide. Restriction of other suicide methods has also shown positive results. The implementation of enhanced restrictions to purchase firearms in the District of Columbia led to reductions in firearm-related suicides (Hassamal et al., 2015).

Policy measures to restrict access to lethal means can include (1) complete removal of a lethal method, (2) reducing the toxicity of a lethal method, for example, reducing carbon monoxide content emissions from vehicles, (3) interfering with physical access, (4) enhancing safety by encouraging at-risk families to remove lethal suicide means from the home, or (5) reducing the appeal of a lethal method by, for example, changing the perception of hanging as a quick and painless death (Hassamal et al., 2015).