During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, military suicide rates increased and surpassed the rates for society at large. The Army has had the highest proportional number of suicides compared to the other services; however, the rates in all the services have been increasing in recent years (USDVA, 2021, September).

Why U.S. military personnel and veterans are at increased risk for suicide compared to civilians is the focus of ongoing research. Military personnel and veterans experience both military- and non-military-related trauma, such as combat-related experiences, military sexual assault, difficulty reintegrating into civilian life, and continued access to guns. Some also have a history of childhood abuse and intimate partner violence. Military personnel and veterans also experience high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder, a known risk factor for both suicidal ideation and behaviors (Holliday et al., 2020).

Elevated suicide risk can endure well beyond military service, with veterans carrying a much greater risk for suicide than their civilian counterparts. Veterans have identified suicide as the most formidable challenge they face. Sadly, approximately 17 veterans die by suicide every day (USDVA, 2021, September).

13.1 Veteran-Specific Data

In Washington, over 63,000 active duty, reserve forces, and civilian men and women serve in the military (Governing.com, 2022). More than 560,000 veterans reside in the state. Although the suicide rate for veterans in Washington is higher than the rate for non-military residents, it is not significantly different from the national veteran suicide rate.

Nationwide, more than 30,000 active-duty service members and veterans of the post 9/11 wars have died by suicide, significantly more than the 7,057 killed in combat. A disproportionate number of service members who die by suicide are young males (in their twenties), White, non-Hispanic in the Army or Marine Corps (Suitt, 2021).

In 2019, 67% of veteran deaths in Washington were the result of firearm injuries (51% nationally). Approximately 37% of Washington veterans who died by suicide were 35 or older (55% nationally) (USDVA, 2021, August). Compared to U.S. civilian adults, the risk for suicide in Washington was:

- 21% higher among veterans

- 18% higher among male veterans

- 2.4 times higher among female veterans (USDVA, 2021, August).

Among Washington’s military families with children, data from Washington’s Healthy Youth Survey indicates that children of military families are at higher risk of suicide. A higher percentage of tenth graders with parents in the military reported symptoms of depression compared to tenth graders from civilian families. The children also answered yes more frequently to questions about serious consideration of suicide, making a suicide plan, and attempting suicide, and fewer than half answered yes when asked if there were adults to whom they could turn for help when feeling sad or hopeless (WSDOH, 2016).

13.2 Military Culture

The military is controlled by civilian leaders who may not fully understand the impact military service has on individuals and families. Military service changes and builds a service member’s identity and introduces them to values and beliefs that may be contrary to what they have experienced in civilian life (WSDOH, 2016).

Intense training and reinforcement of military culture habituates traits within service members that can ultimately be at odds with an individual’s well-being. The military reconfigures civilian practices and ways of speaking. It takes language, symbols, and systems of culture—like religion or national pride—and infuses them with new meaning aimed at military superiority. The military manages and organizes service members’ bodies and minds, cares for them, makes them disciplined tools of the state, empowers them to kill, and deliberately exposes them to harm (Suitt, 2021).

The military’s reliance on guiding principles can overburden individuals with moral responsibility, or blameworthiness for actions or consequences, over which they have little control. Exposure to mental, physical, moral, and sexual trauma, stress and burnout, and continued access to guns can contribute to suicidal ideation (Suitt, 2021).

Masculine military culture can contribute to avoidance of help-seeking behaviors. The dominant masculine identity that pervades the military is one that overwhelmingly favors machismo and toughness; asking for help is at odds with military culture. Acknowledging mental illness is likely to be viewed as a sign of weakness and a potential threat to a person’s career. Service members may be less likely to reflect on their experiences or to seek help for their trauma for fear of looking weak or unmanly in the eyes of their subordinates, peers, and commanding officers (Suitt, 2021).

When soldiers are transferred or moved to other units or when a deployment ends, close, intense relationships formed within units are disrupted. When they leave the military, they may experience feelings of unrest, alienation, anxiety, and lack of purpose. During deployment, family members often become more independent and self-reliant, causing a soldier to feel less needed, believing the family can survive just fine without her or him (WSDOH, 2016).

Source: United States Department of Veteran Affairs.

13.3 Risk Factors for Service Members and Veterans

Several risk factors for suicidal ideation and behaviors have been identified in service members and veterans. Being a young, unmarried male of low rank, a lack of advancement, and reduction in rank can be risk factors. Stress that doesn’t seem to let up, a recent return from deployment, isolation from one’s unit, transferring duty stations, or an adverse deployment experience may contribute to increased risk.

Mental health problems, difficulty returning to civilian life, heavy drinking, and substance use can increase a servicemember’s risk for suicide. Other risk factors for suicidal ideation or suicide include:

- Traumatic experiences and PTSD

- Moral injury

- Military sexual trauma

- Individual moral responsibility

- Access to lethal means (Suitt, 2021).

Modern medical advances have allowed service members to survive increasingly severe physical trauma. However, a person’s quality of life following severe physical trauma can put them at a greater risk of suicidal behaviors. Veterans with severe, prolonged pain stemming from physical trauma are 33% more likely to attempt suicide than those with no, mild, or moderate pain (Suitt, 2021).

Rates were also 24% higher for those who were divorced or separated from their romantic partners or experiencing financial hardship. The Department of Defense points out that these trends follow those of the general population. It is significant that the typical military suicide looks a lot like a typical American civilian suicide (Suitt, 2021).

Reducing risk through safe firearm storage is particularly important for military personnel and veterans because they are more likely to own firearms. Research indicates that the majority of military personnel do not use safe storage practices. Acutely suicidal military personnel are prone to unsafely storing firearms, underreporting suicidal thoughts to military or civilian sources, and failing to disclose access to a firearm (Anestis et al. 2021).

13.4 Interventions

A number of intervention strategies have been successful in reducing suicidal ideation and behaviors. This can include resilience training, stress reduction, and education. Addressing depression and PTSD, encouraging health-promoting behaviors, and the development of programs and crisis lines have had a positive impact.

13.4.1 PREVENTS

In 2019, The President’s Roadmap to Empower Veterans and End a National Tragedy of Suicide (PREVENTS), was signed into law. The program’s goal is to improve existing suicide prevention initiatives and to address gaps in the efforts and services outlined in the first (2001) and updated (2024) National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.

The program includes a website, a nationwide public health campaign, and involvement of individuals and organizations from federal, state, local, and tribal governments, faith-based communities, nonprofit organizations, academia, veteran and military service organizations, and other private industry partners.

For further information, see the VA PREVENTS web page (https://www.va.gov/prevents/).

13.4.2 Defense Suicide Prevention Office

The Defense Suicide Prevention Office (DSPO) provides advocacy, program oversight, and policy for Department of Defense suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention efforts to reduce suicidal behaviors in service members, civilians, and their families.

The DSPO was established in 2011 and is part of the Department of Defense. Its mission is to examine efforts to prevent military suicide. The Department of Defense has developed a holistic approach to suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention using a range of medical and non-medical resources. Grounded in a collaborative approach, DSPO works with the Military Services and other Governmental Agencies, Non-Governmental Agencies, non-profit organizations, and the community to reduce the risk for suicide.

13.4.3 U.S. Air Force Suicide Prevention

The United States Air Force Suicide Prevention Program includes 11 policy and education initiatives designed to change the culture surrounding suicide. The program uses leaders as role models and agents of change, establishes expectations for behavior related to awareness of suicide risk, develops population skills and knowledge, and investigates every suicide. The program represents a fundamental shift from viewing suicide and mental illness solely as medical problems and instead sees them as larger service-wide problems impacting the whole community (CDC, 2022).

The program has been associated with a 33% relative risk reduction in suicide. It was also associated with relative risk reductions in related outcomes, including moderate and severe family violence, homicide, and accidental death. An assessment comparing suicide rates before and after the launch of the program found significantly lower rates of suicide after the program was launched. These effects were sustained over time, except in 2004, during which there was less rigorous implementation of program components than in the other years (CDC, 2022).

13.4.4 Addressing Depression

Major depressive disorder, which is highly comorbid with PTSD, independently increases risk for suicidal ideation and attempts. The Veterans Affairs Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) project uses a depression care liaison to link primary care and mental health services. The depression care liaison assesses and educates patients and follows up with both patients and providers to optimize treatment between primary care visits (CDC, 2022).

This collaborative care supports mental health services by bringing mental health care to the primary care setting, where most patients are first detected and subsequently treated for many mental health conditions. An evaluation of TIDES found significant decreases in depression severity scores among 70% of primary care patients. TIDES patients also demonstrated 85% and 95% compliance with medication and followup visits, respectively (CDC, 2022).

13.4.5 Addressing PTSD

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can occur after someone goes through a traumatic event like combat, assault, or disaster. When you have PTSD, the world feels unsafe. You may have upsetting memories, feel on edge, or have trouble sleeping. You may also try to avoid things that remind you of your trauma—even things you used to enjoy.

Research looking specifically at combat-related PTSD in Vietnam era veterans suggests that the most significant predictor of both suicide attempts and preoccupation with suicide is combat-related guilt. Many veterans experience highly intrusive thoughts and extreme guilt about acts committed during times of war. These thoughts can often overpower the emotional coping capacities of veterans (Hudenko, Homaifar, and Wortzel, 2022).

Veterans and PTSD: Challenging the Misconceptions [2:13]

https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov

Good health is critical to military and family readiness, allowing service members to perform their responsibilities at work and at home to the best of their abilities. Source: Military OneSource.

Practicing good nutrition boosts personal performance. Source: Military OneSource.

With respect to veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, PTSD has been found to be a risk factor for suicidal ideation. Subthreshold PTSD also carries risk. Among these veterans, those with subthreshold PTSD were 3 times more likely to report hopelessness or suicidal ideation than those without PTSD (Hudenko, Homaifar, and Wortzel, 2022).

Veterans with PTSD who felt they have purpose and meaning in life have better outcomes than those who do not. Social support is associated with lower PTSD symptom severity in trauma-exposed individuals. Disrupted sleep is a core symptom of PTSD, and research demonstrates that cognitive-behavioral treatments that reduce insomnia and nightmares can reduce other symptoms of PTSD (DeBeer et al., 2016).

13.4.6 Health-Promoting Behaviors

Health-promoting behaviors, including physical activity and stress management have been shown to decrease suicidal ideation. Those who engage in physical activity or participate in sports are at lower risk for suicidal ideation than those who do not. Individuals who feel they have a purpose in life report lower suicidal ideation than those who did not. In terms of social relationships, there is a significant body of literature identifying social support as a protective factor for suicidal ideation (DeBeer et al., 2016).

Military Stress: PFC Wilson

Background

Private First Class Shania Wilson serves in Alpha Company, 181st Brigade Support Battalion, 81t Brigade Combat Team, Washington Army National Guard. A mother of three, she was stationed at Joint Base Balad for eight months, providing security for the hospital and Iraqi business on base, escorting local nationals working on base, and providing Personal Security Detail services.

A second deployment sent Private Wilson to Afghanistan with the 96th Troop Command based out of Yakima. “I wasn't supposed to be on that deployment, but I was called to duty and had to go,” she reported. She pulled security duty in a variety of places and on several occasions experienced firefights, witnessed the death of three members of her unit, applied first aid to the severely wounded, and on two occasions experienced two separate blasts from an improvised explosive device.

After her deployments, Private Wilson enrolled in college. Several students in one of her classes surmised she was in the military, and she overheard them refer to her one day as a “baby killer.” Recently, a video was shown in her science course that made her feel uncomfortable and since that time she’s had more difficulty concentrating on her studies.

She has not sought any medical or behavioral health assistance for fear that it could interfere with her career in the National Guard and also remove her from the chance to support her unit on another upcoming deployment. In fact, the 81st Brigade Combat Team and 506th Military Police Company received notices of sourcing from the Pentagon, meaning they could be tapped for an upcoming deployment.

Assessment

During a routine medical appointment with a nurse practitioner, the NP noted that Private Wilson kept her eyes down and fidgeted with her cell phone during the initial part of the appointment. When asked how she was feeling, Private Wilson said she was fine except that since returning from her second deployment, she has felt lightheaded with ringing in her ears, has had problems thinking and remembering, and has become more irritable.

”I wasn't supposed to be on that [second] deployment, but I was called to duty and had to go,“ she reported. At school, she reported feeling isolated and uncomfortable and said she wasn’t doing well. She said she wasn’t sleeping well and feels hopeless, like there was no reason to live other than her children and unit. She admitted she had begun to drink heavily. She mentioned that she was worried about a possible deployment and had mixed feelings about returning to duty.

Discussion

Private Wilson experienced significant trauma during her deployments, including the death of her fellow service members. She also appears to be experiencing physical and psychological after-effects of being in close proximity to 2 IED blasts. Although she has expressed mixed feelings about a third deployment, she also expressed a sense of duty and a desire to protect her National Guard career.

What Actions Can You Take?

Private Wilson is clearly having difficulty dealing with her experiences in the war. During the patient assessment, what should you do first?

- Tell Private Wilson that it takes time to recover from a military deployment and she will be fine.

- Report Private Wilson to her supervisor at the Washington Army National Guard.

- Determine Private Wilson’s level of risk for suicidal ideation and behavior by asking open-ended, general questions about safety.

- To safeguard Private Wilson’s safety, have her admitted to a psych ward.

Answer: c

Bottom Line

Any healthcare provider may come in contact with someone who may be at risk for self-harm. Don’t be afraid to ask your patients if they’ve ever tried to harm themselves—as well as how many times and in what ways. Have you practiced questions ahead of time that allow you to assess risk, safety, and lethality? Take a moment to ask those questions right now.

Source: Adapted from Schmidt, 2012.

13.4.7 Veterans Crisis Line

The Veterans Crisis Line encourages veterans and their families and friends to call when a veteran is experiencing a crisis. Those who know a veteran may be the first to recognize emotional distress and reach out for support when issues reach a crisis point—and well before a veteran is at risk of suicide. The Veterans Crisis Line has specially trained responders who can help veterans of all ages and circumstances. Some of the responders are veterans themselves and they understand what veterans and their families and friends have been through and the challenges they face (USDVA, 2022, May).

Since its launch in 2007, the Veterans Crisis Line has answered nearly 6.2 million calls and initiated the dispatch of emergency services to callers in crisis nearly 233,000 times. The Veterans Crisis Line anonymous online chat service, added in 2009, has been used more than 739,000 times (USDVA, 2022, May).

In November 2011, the Veterans Crisis Line introduced a text-messaging service to provide another way for veterans to connect with confidential, round-the-clock support. Since then, it has responded to more than 253,000 texts. Text the Veterans Crisis line at 838255 (USDVA, 2022, May).

Source: VeteransCrisisLine.net

In 2020, the Caring Letters program was added. It focuses on mailing letters to veterans during the year after their initial documented call to the Veterans Crisis Line. This initiative has been found to reduce the rate of suicide death, attempts, and ideation and provides a unique opportunity to help save veteran lives beyond the call (USDVA, 2022, May).

A Peer Support Outreach Call Center was opened in 2021, staffed by trained Veterans who proactively reach out to Veterans Crisis Line callers who might benefit from additional intervention. Studies show that veterans who have peer mentors are more likely to keep their VA appointments, access additional treatment methods, and meet other important health benchmarks. With this in mind, peer specialists give veterans a sense of empowerment, reduce stigma, and provide guidance on self-help and goal setting (USDVA, 2022, May).

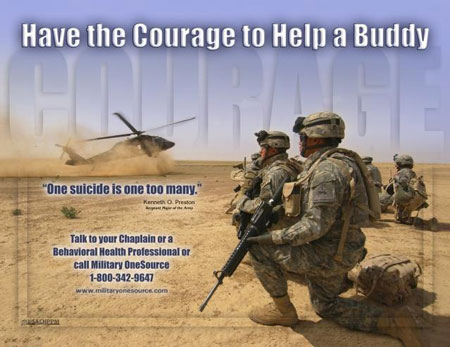

U.S. Army suicide prevention poster. Source: United States Army.

A Soldier’s Story

A soldier who had joined the Washington National Guard after returning from deployment came into the Joint Services Support (JSS)* office at Camp Murray in Tacoma Washington, asking for help finding a job. While talking with the Employment Transition Team, the soldier revealed financial struggles, fear of returning home because of domestic violence, overwhelming depression, and suicidal thoughts.

The JSS multidisciplinary team sprang into action. Five weeks later the soldier had a regular therapy schedule, gift cards for food and gas, an electronic benefits card, a refreshed résumé, a suicide prevention mentor, an order of protection against the abusive partner, and safe transitional housing. Outstanding disability claims were resolved, and, as the soldier was about to move into an apartment, a job offer came through from a prominent Washington company. The soldier’s life moved from a place of desperation to a place of stability.

It is not unusual for a person seeking help to have multiple needs spanning many systems. What is unique is that this soldier had the ability to get all of these needs met in one place by a collaborative, supportive team of professionals, each of whom was well-trained and attuned to depression and suicide risk.

The JSS states that its purpose is to “enhance the quality of life for all Guard members, their families, and the communities in which they live and contribute to readiness and retention in the Washington National Guard.” The JSS at Camp Murray combines strong and supportive leadership, cross-system teamwork, and attention to soldiers’ emotional needs and ability to thrive at work—a program model that improves job performance and saves lives.

*Joint Services Support (JSS) Directorate: a centralized support center for all Washington Guardsmen and women, reserve, veterans, and family members offering family readiness programs and services. Call 1-800-364-7492 (Available 24 hours).

Source: WSDOH, 2016.