Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia. About 5 million people in the United States live with the effects of Alzheimer’s, making it our sixth leading cause of death. About two-thirds of Americans with Alzheimer’s disease are women (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017).

Adult Day Care

Adult day service centers provide non-residential coordinated services in a community setting for less than a day. There are three types: (1) social, (2) medical/health, and (3) specialized (providing programs for people with dementia) (Siegler et al., 2015). In Florida, a specialty license is needed to provide services as a Specialized Alzheimer’s Services Adult Day Care Center (O’Keefe, 2014). There are approximately 4,800 adult day service centers in the United States (Rome et al., 2015) serving nearly 300,000 people (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016).

Did You Know. . .

Adult day care is a program of therapeutic social and health services as well as activities for adults who have functional impairments. Services are provided in a protective, non-institutional environment. Participants may utilize a variety of services offered during any part of a day, but for less than a 24-hour period.

The social model is designed for individuals who need supervision and activities but not extensive personal care and medical monitoring. The medical model provides more extensive personal care, medical monitoring, and rehabilitative services in addition to structured and stimulating activities (O’Keefe et al., 2014)

In Florida, there are approximately 287 adult day care centers, that provide therapeutic programs, social services, and health services, as well as activities for adults in a non-institutional setting (AHCA, 2017). Overall, approximately one-third of adult day care clients have Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016). Although it is common for adult day care centers to cater to a significant number of clients with dementia, there are approximately 15 specialized adult day care centers in Florida specifically designated to treat clients with dementia. The specialized centers enroll a higher percentage of clients with dementia and require specialized dementia training for their staff.

Adult day care clients are younger and more racially and ethnically diverse than users of other long-term care services. More than one-third of adult day care clients are non-white, 17.3% of services users are non-Hispanic black, and 20.3% of services users are Hispanic (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016).

Two-thirds of participants attend at least 3 days/week (Siegler et al., 2015). Normally the client is collected by a transport service and brought home again at the end of the day. Day care relieves the family caregiver of nursing duties and is effective in reducing caregivers’ subjective burden and depression. The degree of usage of day care varies from 4.2% to 61.0% (Donath et al., 2011).

In this course we will discuss Alzheimer’s disease and other common types of dementia from the perspective of workers and clients in a specialized adult day center. We will describe how dementia affects the brain and how Alzheimer’s disease differs from other types of dementia. We will go over behaviors you may see in people with mild, moderate, and severe dementia and discuss communication issues you might see at different stages of dementia.

The course will also describe activities you can do with your clients and how to assist them with their activities of daily living. We will describe family issues and stressors for people caring for someone with dementia and will share some innovative ideas about “therapeutics environments” as well as how to recognize and handle ethical issues in your clients with dementia.

How the Brain Works

The Human Brain

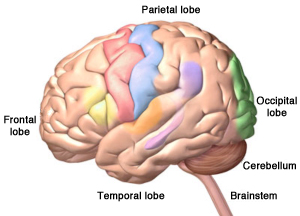

The four lobes of the cerebrum, plus the cerebellum and the brainstem. Alzheimer’s disease starts in the temporal lobe. Copyright, Zygote Media Group, Inc. Used with permission.

Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia are caused by damage to the brain. The most significant and obvious damage occurs in the critically important part of the brain called the cerebrum. The cerebrum fills up most of our skull and is divided into four lobes (one on each side of the brain):

- Frontal lobes

- Temporal lobes

- Parietal lobes

- Occipital lobes

The cerebrum allows us to think, form memories, communicate, make decisions, plan for the future, and act morally and ethically. It also controls our emotions, helps us make decisions, and helps us tell right from wrong. The cerebrum also controls our movements, vision, and hearing. When dementia strikes, brain cells in the cerebrum begin to shrink and die. As the damage progresses, brain cells are no longer able to communicate with one another as well as they did in the past. Not surprisingly, as more and more brain cells are damaged, connections are lost, pathways are disrupted, and eventually people with dementia lose many brain functions.

The human brain has two other important parts: the cerebellum and the brainstem. Touch the back part of your head just below the occipital lobes. The cerebellum is right there. It is involved with coordination and balance.

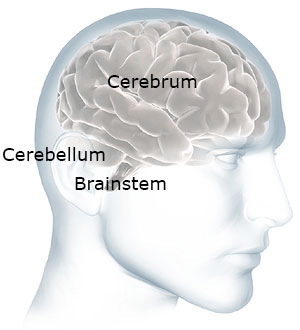

The cerebellum and brainstem are at the back of your head below the cerebrum. Used with permission.

Now move your hand a little down and stop before your get to your spine. The brainstem is right there—at the back of the head, above your spine. It connects the brain to the spinal cord. The brainstem oversees automatic functions such as breathing, digestion, heart rate, and blood pressure. Although it is possible for the brainstem and cerebellum to be damaged by stroke or traumatic injury, they are generally not affected by dementia.

The brain is a communications center consisting of billions of neurons, or nerve cells. It is the most complex organ in the body. This three-pound mass of gray and white matter is at the center of all human activity—you need it to drive a car, to enjoy a meal, to breathe, to create an artistic masterpiece, and to enjoy everyday activities. The brain regulates your body’s basic functions; it enables you to interpret and respond to everything you experience and shapes your thoughts, emotions, and behavior (NIDA, 2014).

Networks of neurons pass messages back and forth among different structures within the brain, the spinal cord, and the nerves in the rest of the body (the peripheral nervous system). These nerve networks coordinate and regulate everything we feel, think, and do (NIDA, 2014). Dementia interrupts the efficient function of these networks, affecting every aspect of a person’s life.

Defining Dementia

Dementia is a group of symptoms impacting cognitive functions such as memory, judgment, reasoning, and social skills as well as interfering with the ability to function in daily life. It is progressive, meaning it gets worse over time. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common kind of dementia. AD begins in the area of the brain that makes new memories. That’s why someone with AD forgets something that happened just a moment ago.

Alzheimer’s disease isn’t the only cause of dementia and, unfortunately, there is no way to know for sure what type of dementia a person has. There is no blood test or x-ray that can diagnose Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia. The only sure way to know if someone had Alzheimer’s disease is to examine their brain after they die.

Symptoms are a little different in each type of dementia. It’s good to know the difference to help you understand why someone is acting the way they are. Characteristics of Alzheimer’s dementia will be described in module 2.

Frontal-Temporal Dementia

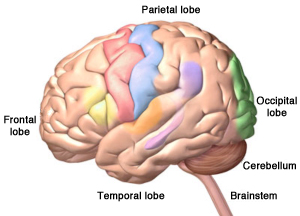

Look at the picture of the brain below. Put your hand on your forehead. The part of your brain just behind your forehead is called the frontal lobe. Now slide your fingers from the front to the side of your head (your temple). This part of the brain is called the temporal lobe.

Damage to the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes causes forms of dementia called frontotemporal disorders. Copyright, Zygote Media Group, Inc. Used with permission.

There is a type of dementia that affects this part of the brain. It is called frontal-temporal dementia. It is thought to be the most common type of dementia in people under the age of 60. It’s not nearly as common as Alzheimer’s and it starts at a much younger age.

We use the front part of our brain to make decisions, to tell right from wrong, to control our emotions, and to plan for the future. Someone with dementia in this part of the brain will have poor judgment and lose the ability to tell right from wrong. They also have less control over their behavior.

So instead of losing short-term memory like people with Alzheimer’s disease, a person with frontal-temporal dementia might start doing things that are confusing to their friends and family. They might steal, even though they have never stolen in the past. They might make inappropriate sexual remarks or engage in inappropriate sexual behaviors, even though they’ve never done these things in the past.

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia is caused by lots of small strokes. This can happen when people don’t control their high blood pressure. Generally, vascular dementia doesn’t affect memory as much as Alzheimer’s. This is because the damage is spread throughout the brain. Vascular dementia causes mood changes that are stronger than the mood changes you might see in someone with Alzheimer’s. It can also affect judgment—but not as strongly as in someone with frontal-temporal dementia.

You might have cared for more than one client with vascular dementia because many older adults have high blood pressure that isn’t under good control. You may also see vascular dementia in someone who has had a stroke.

Lewy Body Dementia

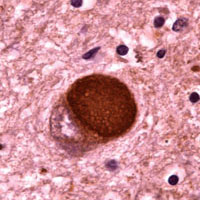

Microscopic image of a Lewy body. Courtesy of Carol F. Lippa, MD, Drexel University College of Medicine. Source: Alzheimer’s Disease Information and Referral Center.

Lewy body dementia is less common than Alzheimer’s dementia, frontal-temporal dementia, or vascular dementia. It is responsible for a little less than 5% of all cases of dementia. People with Parkinson’s disease can have this type of dementia. Lewy body dementia happens when tiny unwanted molecules form in the brain. These unwanted molecules (Lewy bodies) become scattered throughout the brain.

People with Lewy body dementia usually don’t have problems with memory, at least at first. But they can have hallucinations, mental changes, and sudden confusion. These symptoms can come and go throughout the day. Lewy body dementia can also affect sleep and cause a person to suddenly faint or pass out. This means a person with Lewy Body dementia is at high risk for unexpected falls.

Comparison of Dementia Types | |

|---|---|

Type of Dementia | Characteristics and Symptoms |

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) |

|

Frontal-temporal dementia |

|

Vascular dementia |

|

Dementia with Lewy bodies |

|

How Dementia Affects the Brain

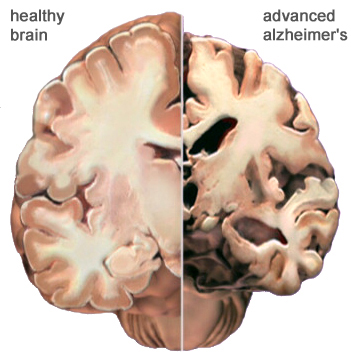

Normal Brain Contrasted with

AD Brain

A view of how Alzheimer’s disease changes the whole brain. Left side: normal brain; right side, a brain damaged by advanced AD. Source: Courtesy of The Alzheimer’s Association. Used with permission.

Dementia changes the entire brain. In Alzheimer’s disease, nerve cells in the brain die and are replaced by abnormal proteins called plaques and tangles. As the nerve cells die, the brain gets smaller. Over time, the brain shrinks, affecting nearly all its functions.

Alzheimer’s disease usually affects memory and emotional control before other symptoms are obvious. Other types of dementia, because the damage is to another part of the brain, will have different symptoms. Although dementia can start in one part of the brain, eventually it will affect the entire brain.

Normal Age-Related Changes

We all experience physical and mental changes as we age. Some people become forgetful when they get older. They may forget where they left their keys. They may also take longer to do certain mental tasks. They may not think as quickly as they did when they were younger. These are called age-related changes. These changes are normal—they are not dementia.

Age-related changes don’t affect a person’s life very much. Someone with age-related changes can easily do everything in their daily lives—they can prepare their own meals, drive safely, go shopping, and use a computer. They understand when they are in danger and continue to have good judgment. They know how to take care of themselves. Even though they might not think or move as fast as when they were young, their thinking is normal—they do not have dementia.

The table below describes some of the differences between someone who is aging normally and someone who has dementia.

Normal Aging vs. ADRD | |

|---|---|

Normal aging | AD or other dementia |

Occasionally loses keys | Cannot remember what a key does |

May not remember names of people they meet | Cannot remember names of spouse and children—don’t remember meeting new people |

May get lost driving in a new city | Get lost in own home, forget where they live |

Can use logic (for example, if it is dark outside it is night time) | Is not logical (if it is dark outside it could be morning or evening) |

Dresses, bathes, feeds self | Cannot remember how to fasten a button, operate appliances, or cook meals |

Participates in community activities such as driving, shopping, exercising, and traveling | Cannot independently participate in community activities, shop, or drive |

In some older adults, memory problems are a little bit worse than normal age-related changes. When this happens, the person has mild cognitive impairment, also called MCI.

Mild cognitive impairment isn’t dementia. You won’t generally see personality changes, just a little more difficulty than is normal with thinking and memory. For some people, mild cognitive impairment gets worse and develops into dementia, but this doesn’t happen with everyone.

Video: Dementia 101 (5:49) Teepa Snow

Other Causes of Dementia. http://teepasnow.com/resources/teepa-tips-videos/dementia-101/

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia is based on symptoms; no test or technique that can diagnose dementia. Nevertheless a thorough examination that includes a physical exam, blood work, biopsychosocial interview, family interview, and a neuropsychological evaluation should be completed.

Neuroimaging shows promise is assisting with early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease by detecting visible, abnormal structural and functional changes in the brain (Fraga et al., 2013). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide information about the shape, position, and volume of the brain tissue. It is being used to detect brain shrinkage, which is likely the result of excessive nerve death. Positron emission tomography (PET) is being used to detect the presence of beta amyloid plaques in the brain.

To guide clinicians, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) has developed the following diagnostic guidelines indicating the presence Alzheimer’s disease:

- Gradual, progressive decline in cognition that represents a deterioration from a previous higher level;

- Cognitive or behavioral impairment in at least two of the following domains:

- episodic memory,

- executive functioning,

- visuospatial abilities,

- language functions,

- personality and/or behavior;

- Functional impairment that affects the individual’s ability to carry out daily living activities;

- Symptoms that are not accounted for by delirium or another mental disorder, stroke, another type of dementia or other neurological condition, or the effects of a medication. (DeFina et al., 2013)