A trigger is a prompt or external stimulus that leads to a behavior or causes a response—something that “sets you off.” Triggers tell us “Do something now!” A trigger can be internal (fatigue, frustration, anger, desire) or external (a crying baby, a remark). It is known that certain triggers and risk factors increase the likelihood of a parent or caregiver’s abusing an infant.

A risk factor is any characteristic of a person, a situation, or a person’s environment that increase the likelihood that a person will engage in a particular behavior.

Triggers and risk factors are often related. For example, a crying baby often affects a mother’s sleep, triggering frustration on the part of the mother. The mother’s frustration may in turn trigger an emotional response in her male partner, telling him to “do something now.” The trigger is associated with the mother’s frustration and tiredness but the acting out often happens with the male. Helping parents and caregivers understand what triggers abusive behavior is the first step in preventing child abuse.

Triggers Associated with Shaking a Baby

Episodes of Crying

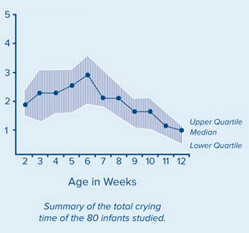

Inconsolable or excessive crying is the most common trigger for shaking a baby. Episodes of crying typically increase in the first month after birth, peak in the second month, and decrease thereafter (Parks et al., 2012). This is expressed in the chart below, which shows the normal and expected hours of fussing and crying from birth to 3 months of age.

Infant Fussing per 24 Hours, Birth to 3 Months

Source: CDC.

Source: CDC.

Infant crying can be a frustrating issue for parent and caregivers who may not understand that crying is a normal development stage and will decline as the baby ages. A parent’s perception of crying as a problem is the most common risk factor for SBS. Problem crying is also associated with early weaning from breast milk, frequent changes of formula, and parent depression symptoms (Cook et al., 2012).

Colic and the Rule of Threes (Wessell Criteria)

According to many experts, colic is inconsolable crying in an infant that lasts many hours a day, starting in the second week of life and lasting until about 3 months of age. About forty years ago, a pediatrician named Morris Wessel conducted a breakthrough study on excessively fussy children. The definition he chose to describe colicky babies was not considered scientific, but it stuck with physicians.

Wessel’s definition of a colicky infant was a child who cried for more than 3 hours a day, for more than 3 days a week, for over 3 weeks. This is often referred to as the Rule of Threes and these rules came to be known as the Wessell Criteria, which are now used in most current studies of babies with colic (Amer Preg Assoc, 2013).

The natural course of infant colic symptoms appear by around 3 weeks, peak at 8 weeks, and remit beyond 12 weeks of a term infant’s chronological age. Infant colic affects up to 20% of infants under 3 months. Infant colic has significant adverse effects on maternal mental health and family quality of life and is a trigger for child abuse and a risk factor for shaken baby syndrome. Infants in whom crying persists beyond 3 months are at risk of adverse outcomes in the school years, including anxiety, aggression, hyperactivity, allergy, and sleep disorders, and at more than double the risk of poor mental health in later years (Sung et al., 2012).

Infant Sleep Problems

Fifteen to thirty-five percent of parents report problems with their infant’s sleep during the first 6 months of life. Common sleep problems include difficulty getting the infant to sleep at the start of the night and difficulty re-settling the infant overnight (Cook et al., 2012).

Preventing infant sleep problems may reduce rates of parental depression, which is particularly important with breast feeding mothers who may be reluctant to accept pharmacologic treatment for depression (Cook et al., 2012).

Maternal Fatigue and Depression

Postpartum maternal tiredness/fatigue is defined as an imbalance between activity and rest. Fatigue is a state which persists through the circadian rhythm and cannot be relieved through a single period of sleep (Kurth, et al, 2010).

Most new mothers report problems with tiredness or fatigue, and disquieting infant crying is the most commonly reported reason parents consult a health professional. Not surprisingly, the occurrence of postnatal tiredness is associated with the amount of infant crying. In the worst case, infant crying and increasing exhaustion can accumulate into a vicious circle and negatively affect family health (Kurth et al., 2010).

Comforting a crying baby while coping with personal tiredness can be a challenge. Maternal exhaustion has been identified as a predictor of postpartum depression, and persistently crying infants are at a higher risk for shaken baby syndrome or other forms of child abuse (Kurth et al., 2010).

Risk Factors for Child Maltreatment

There is really no particular personality type that’s at risk. We all are at risk, and I think that it would be unfair of us to think that none of us can get frustrated by a crying baby. And we’ve all been frustrated by babies who are just crying, but most of us have the social support, we have some knowledge, we have self-control that we don’t take these frustrations out on our really helpless young infants. But there are individuals, who because of what’s going on and the stress that they have in their lives and the lack of social supports and their self-esteem and sometimes their lack of knowledge, they do take these frustrations out on babies.

We know that the majority of perpetrators of abusive head trauma are men, but we use that really in terms of thinking about prevention because women can harm children just as well as men. We also know that one of the strong risk factors is having an unrelated adult living in a household; we have many cases where a young mother, or a mother of a young baby, has a boyfriend living in the house. The boyfriend may not be biologically related to the child, and often when that young man is left in a caregiving role for that child, sometimes bad things happen. Those kinds of risk factors help us target prevention efforts and help us think about prevention, but in my mind, really, any adult who is tired and stressed, who is dealing with an irritable crying baby, is at risk.

Cindy Christian, MD

NICHD, 2013

Risk factors are characteristics associated with child maltreatment—they may or may not be direct causes. Certain characteristics have been found to increase a child’s risk of being maltreated or a parent or caregiver’s risk of abusing a child.

Although all caregivers are at risk for shaking a child, the presence of substance abuse, domestic violence, and mental health issues greatly increases the risk for an adult’s committing child abuse or neglect. There is a higher incidence of fatalities and near-fatalities when these three factors are present (DCBS, 2012).

Many abusive parents believe that children exist to satisfy parental needs and that the child’s needs are unimportant. Abusive parents may show disregard for the child’s own needs, feelings, and limited abilities. Children who don’t satisfy the parent’s needs may become victims of child abuse.

Risk Factors for Victimization

According to Child Protective Services (CPS), more than 3.7 million children in the United States were the subjects of at least one CPS report in 2011. About 20% of these children were found to be victims of some sort of abuse (Children’s Bureau, 2011).

Nationally, victims in the age group of birth to 1 year have the highest rate of victimization. This is split between the sexes, with boys accounting for 48.6% and girls accounting for 51.1%. Eighty-seven percent of victims were comprised of three races or ethnicities: White (43.9%), African American (21.5%), and Hispanic (22.1%) (Children’s Bureau, 2011).

Special needs that may increase caregiver burden such as disabilities, mental retardation, mental health issues, and chronic physical illnesses also put a child at increased risk for maltreatment.

In the 2012 review of child abuse cases in Kentucky, the Department of Community Based Services (DCBS) uncovered the following risk factors that appeared to increase an infant’s risk of being shaken, particularly when combined with a parent or caregiver who is not prepared to cope with caring for a baby:

- Babies less than 1 year of age

- Infant prematurity or disability

- Being one of a multiple birth

- Prior physical abuse or prior shaking

Risk Factors for Perpetration

A perpetrator is the person who is responsible for the abuse or neglect of a child. Perpetrators come from all walks of life, races, ethnicities, religions, and nationalities. They come from all professions and represent all levels of intelligence and standards of living. There is no single social group free from incidents of child abuse.

In 2011 the Children’s Bureau, using data from CPS reports, found that for all forms of child abuse and neglect:

- Four-fifths (84.6%) of perpetrators were between the ages of 20 and 49 years.

- Four-fifths (80.8%) of perpetrators were parents.

- Of the perpetrators who were parents, 87.6% were the biological parents. (Children’s Bureau, 2011)

Analysis of perpetrator’s confessions indicate that the majority of perpetrators are male and are most likely to be fathers, followed by boyfriends, female babysitters, and mothers, in descending order (Chiesa and Duhaime, 2009).

Parents who lack an understanding of a child’s needs or who lack child development and parenting skills are at increased risk for maltreating a child under their care. Parents with a history of child maltreatment in their own family and parental thoughts and emotions that tend to support or justify maltreatment behaviors are also at increased risk of maltreating a child.

Substance abuse and mental health issues (eg, depression) put a parent or caregiver at increased risk for committing child abuse. Parental characteristics such as young age, low education, single parenthood, large number of dependent children, and low income are also risk factors for committing child maltreatment. A nonbiological transient caregiver in the home—such as the mother’s male partner—is a risk factor for child abuse.

Family Risk Factors

Social isolation, family disorganization, dissolution, and violence—including domestic violence—are risk factors for a parent of caregiver committing child abuse. If a parent is stressed, has a poor relationship with the child, or engages in negative interactions with the child, they are at increased risk for committing child abuse.

Children may be in a caretaker role—for example, as a babysitter—and may be responsible for abusing a child in their care. Any adult caretaker may be considered responsible if they delegate care responsibilities to an inappropriate minor caregiver. A mandatory reporter who suspects that abuse has occurred when one child is caring for another is required by law to make a child abuse report.

Community Risk Factors

Certain factors within the community can increase the risk of a parent or caregiver’s committing child abuse. Community violence, high community poverty rates, residential instability, high unemployment rates, high density of alcohol outlets, and poor social connections can increase the likelihood of a parent or caregiver abusing a child under their care.

Six Factors Protective Against Child Maltreatment

Protective factors are those factors that reduce or eliminate the risk of an infant’s being shaken or abused. Protective factors serve as buffers, helping parents who might otherwise be at risk of abusing their children to find resources, supports, or coping strategies that allow them to parent effectively, even under stress.

Certain protective factors decrease a child’s risk of being abused while other protective factors decrease a parent or caregiver’s risk of abusing a child. Six specific protective factors have been shown to be particularly effective in the prevention of child abuse. Research has shown that these protective factors are linked to a lower incidence of child abuse and neglect (CWIG, 2013).

1. Nurturing and Attachment

A child’s early experience of being nurtured and developing a bond with a caring adult affects all aspects of behavior and development. When parents and children have strong, warm feelings for one another, children develop trust that their parents will provide what they need to thrive, including love, acceptance, positive guidance, and protection (CWIG, 2013).

2. Knowledge of Parenting and Child Development

Discipline is both more effective and more nurturing when parents know how to set and enforce limits and encourage appropriate behaviors based on the child’s age and level of development. Parents who understand how children grow and develop can provide an environment where children can live up to their potential. Child abuse and neglect are often associated with a lack of understanding of basic child development or an inability to put that knowledge into action. Timely mentoring, coaching, advice, and practice may be more useful to parents than information alone (CWIG, 2013).

3. Parental Resilience

Resilience is the ability to handle everyday stressors and recover from occasional crises. Parents who are emotionally resilient have a positive attitude, creatively solve problems, effectively address challenges, and are less likely to direct anger and frustration at their children. In addition, these parents are aware of their own challenges—for example, those arising from inappropriate parenting they received as children—and accept help and/or counseling when needed (CWIG, 2013).

4. Social Connections

Evidence links social isolation and perceived lack of support to child maltreatment. Trusted and caring family and friends provide emotional support to parents by offering encouragement and assistance in facing the daily challenges of raising a family. Supportive adults in the family and the community can model alternative parenting styles and can serve as resources for parents when they need help (CWIG, 2013).

5. Concrete Supports for Parents

Many factors beyond the parent-child relationship affect a family’s ability to care for their children. Parents need basic resources such as food, clothing, housing, transportation, and access to essential services that address family-specific needs (eg, childcare, healthcare) to ensure the health and well-being of their children. Some families may also need support connecting to social services such as alcohol and drug treatment, domestic violence counseling, or public benefits. Providing or connecting families to the concrete supports that families need is critical. These combined efforts help families cope with stress and prevent situations where maltreatment could occur (CWIG, 2013).

6. Social and Emotional Competence of Children

Just like learning to walk, talk, or read, children must also learn to identify and express emotions effectively. When children have the right tools for healthy emotional expression, parents are better able to respond to their needs, which strengthens the parent-child relationship. When children’s age, disability, or other factors affect their needs and the child is incapable of expressing those needs, it can cause parental stress and frustration. Developing emotional self-regulation is important for children’s relationships with family, peers, and others (CWIG, 2013).

Professional Training

Providing training about protective factors for all people who work with children and families helps build a workforce with common knowledge, goals, and language. Professionals, from frontline workers to supervisors and administrators, can benefit from training that is tailored to their role and imparts a cohesive message focused on strengthening families.

Strategies for enhancing professional development:

- Provide trainings on protective factors to current trainers so they can teach others.

- Integrate family-strengthening themes and the protective factors into college, continuing education, and certificate programs for those working with children and families.

- Incorporate family-strengthening concepts into new-worker trainings.

- Develop online training and distance learning opportunities.

- Provide training at conferences and meetings.

- Reinforce family-strengthening training with structured mechanisms for continued support, such as reflective supervision and ongoing mentoring (CWIG, 2013)