For reasons inexplicable to many physicians, and unbeknownst to many others, the diagnosis of abusive head trauma/shaken baby syndrome remains a lightning rod for controversy. Public media articles continue to be published. Legal articles continue to be written. And judicial commentary on the science continues to occur.

Narang et al., 2013

Although shaken baby syndrome/abusive head trauma is known by many names, and disagreement continues over its exact causes, abusive head trauma has long been recognized as a clinically valid medical diagnosis (Narang, 2011). As far back as 1974, Caffey described a constellation of injuries that included subdural hematoma, long-bone fractures, and retinal hemorrhages. If this occurred in the absence of a reasonable history of trauma or other medical condition, Caffey referred to these injuries as “the whiplash shaken infant syndrome.” These types of injuries continue to be hallmarks for abusive head injury (Chiesa and Duhaime, 2009).

Clinical Presentation

During the initial interview, healthcare providers should be aware of a possible SBS/AHT injury in any infant or young child who presents with a history that is not plausible or consistent with the presenting signs and symptoms. During the initial assessment, ask who is caring for the child and be alert for the presence of a new adult partner in the home. The absence of a primary caregiver at the onset of injury or illness should be noted. If the parent or caregiver has delayed seeking medical care for the child in the past, or if there is a previous history or suspicion of abuse, child abuse may be suspected.

During the physical exam, physical evidence of multiple injuries at varying stages of healing or unexplained changes in neurologic status, unexplained shock, or cardiovascular collapse are indicators of possible abuse. If a traumatic cause of injury is not obvious, careful assessment is warranted (Chiesa and Duhaime, 2009). Pay close attention to skin, abdominal, and skeletal systems to assess for additional trauma. In addition to a thorough history and physical exam, ophthalmologic examination, computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and skeletal surveys may be used in the diagnosis of SBS/AHT.

Symptoms and Types of Childhood Injuries

In some cases, even though extensive damage may have occurred, there may not be any physical signs of injury (bruising, bleeding, swelling). Accidental childhood injuries usually involve bony areas such as shins, elbow, and knees. Toddlers learning to walk will fall and skin or bruise these areas, just as slightly older children may do the same while learning to ride a bicycle. Suspicious injuries usually occur in areas that are not susceptible to accidental injuries typical for the child’s age (NYSOCFS, 2011).

Evaluating Bruising Areas

Copyright 2011 Research Foundation of SUNY/BSC/CDHS. All rights reserved.

Although subdural hematoma, retinal hemorrhage, and cerebral edema are the best-known indicators of SBS/PAHT, additional symptoms, which can vary from mild to severe, should be noted:

- Brain damage

- Spinal cord injury

- Seizures

- Decreased alertness

- Extreme irritability or other changes in behavior

- Lethargy, sleepiness, not smiling

- Loss of consciousness, pale or bluish skin

- Not breathing or difficulty breathing

- High-pitched cry

- Lack of appetite, vomiting

- Increased head circumference, which may indicate chronic subdural hematoma

A number of conditions can mimic abusive head injury. These include birth trauma, congenital malformations, accidental trauma, genetic and metabolic conditions, infectious diseases, hematologic disorders, surgical complications, toxins, vasculitides (inflammation of blood vessels), nutritional deficiencies, and oncologic processes (Chiesa and Duhaime, 2009).

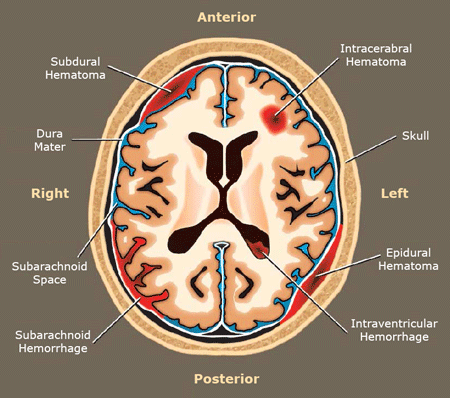

Hematoma Types in the Brain

Source: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2012.

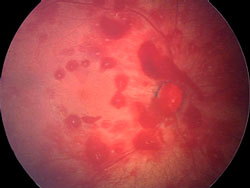

Retinal Hemorrhage

Retinal hemorrhage in an infant subject to abusive head trauma. Courtesy University of Edinburgh students (wiki).

Suspected abusive head trauma may present with a spectrum of symptoms, from mild to severe. In mild cases, signs and symptoms such as irritability, sleepiness, vomiting, or poor feeding are common to a wide variety of pediatric illnesses or injuries.

In the case of more severe injuries, subdural and/or subarachnoid hemorrhage with varying degrees of neurologic signs and symptoms, retinal hemorrhage, physical or radiologic evidence of contact to the head, upper cervical spine injuries, and skeletal injuries may be present (Chiesa and Duhaime, 2009).

Accidental injuries, often related to falls, are a commonly reported cause of head injury in children. When researchers at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio looked at evidence about short falls (a fall of less than 1.5 meters), they concluded:

- When caregivers have been surveyed, they report that short falls are common, but severe injuries from short falls are rare.

- Short falls occurring in objective settings, such as hospitals, have not resulted in subdural hematoma or death.

- Children in large, licensed daycares rarely die from short falls.

- Well-designed, prospective studies reveal that severe injuries or death resulting from short falls are rare events.

- Systematic reviews of the short fall literature indicate that short falls rarely cause death in children.

Completing the Diagnosis

A diagnosis begins with the chief complaint and the presenting symptoms. This is followed by a complete medical history, a detailed trauma history, and a complete physical examination. Gathering information from social services and other medical specialties (radiology, neurology, ophthalmology) provides important history and perspective. Keep in mind that, in the vast majority of cases, the common denominator for subdural hematoma and retinal hemorrhage is trauma (Narang, 2013).

More than any other diagnosis, a clinician who suspects child abuse must consider inconsistencies, which may include a history that is:

- Absent in the presence of severe injuries

- Inconsistent with the known developmental capabilities of the child

- Pathophysiologically inconsistent with the injuries

- Inconsistent with clinical studies and statistical information on subdural hematomas and retinal hemorrhages (Narang, 2013)