In the next 17 seconds, an older adult will be treated in a hospital emergency department for injuries related to a fall. In the next 30 minutes, an older adult will die from injuries sustained in a fall. Falls are the leading cause of injury among adults aged 65 years and older in the United States, and can result in severe injuries such as hip fractures and head traumas. Many older adults, even if they have not suffered a fall, become afraid of falling and restrict their activity, which drastically decreases their quality of life.

As the U.S. population ages, both the number of falls and the costs to treat fall injuries are likely to increase. The annual cost of fall injuries for older Americans is estimated to be $50 billion. Having information on the economic burden of older adult falls can help make the case to fund prevention programs and reduce overall healthcare costs.

Falls and fall-related injuries in older adults are widespread, expensive, and largely avoidable. They are responsible for significant disability, reduced physical function, and loss of independence. More than one-third of people aged 65 and older fall each year, and those who fall once are 2 to 3 times more likely to fall again, making falls an urgent public health issue.

Preventing falls in older adults is a stated priority of the Affordable Care Act, which promotes and strengthens policies and programs to prevent falls, especially among older adults. The act’s goal is to enhance cooperation and collaboration between clinical and community-based prevention efforts and increase the availability and use of falls-prevention programs. It stresses the importance of exercise programs to increase strength and balance, medication review and modification to eliminate all but essential drug treatments, home modifications, and vision screening (National Prevention Council, 2012).

The National Council on Aging (NCOA) updated its Falls Free National Action Plan in 2015 with numerous evidence-based strategies designed to reduce the growing number of falls. It is a blueprint describing what should be done to reduce the growing number of falls and fall-related injuries among older adults. The plan is the product of key recommendations and strategies collected during the Falls Prevention Summit, a White House Conference on Aging event held in April 2015. The strategies focus on physical mobility, medications management, and home and environmental safety. NCOA provides extensive resources through its Falls Free Initiative, which aids communities, states, federal agencies, nonprofits, businesses, and older adults and their families in their fight against falls (NCOA, 2023).

The leadership and direction provided by these and other organizations is bringing much-needed evidence-based falls prevention information to healthcare providers and the public. But identifying whether a person is at risk for falls can be surprisingly complicated, and treating the underlying balance deficit can be even more so. Ideally, the process involves an interdisciplinary team of healthcare providers knowledgeable about when to screen, intervene, refer, and treat. In reality, there are a host of reasons why we often fall short of that goal, which points to the need for education and training across the spectrum of healthcare providers.

Video: News on Falls (3 min, 35 sec)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RaCLbCnktfE

1.1 Balance, Postural Control, and Falls

As a medical professional, you may take balance for granted in your own life and even in the lives of people you see in the workplace. You may find yourself thinking about balance when a patient falls—then perhaps only in terms of administering help, filling out paperwork, contacting family members, or considering whether to order a restraint or medication.

But what is balance and postural control? And what, exactly, is a fall? Let’s begin by defining these terms.

1.11 Balance

A woman demonstrating superb balance by standing tip-toed on a champagne bottle. Source: Wikipedia and the Library of Congress.

For the vast majority of young and middle-aged adults, our feet, legs, torso, and head stay aligned without effort and we rarely think about the danger of falling. In some older adults and in those with balance impairments due to illness or injury, balance can be more difficult. In extreme cases, the body becomes an unwieldy tower of uncontrolled levers that seems suddenly incapable of sustaining itself in the upright position.

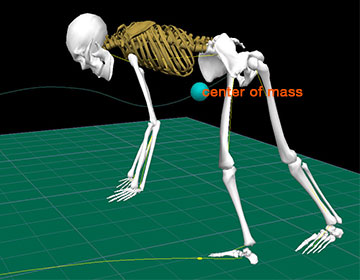

Technically, balance, or postural stability, is the ability to automatically and accurately maintain your center of mass (i.e., center of gravity) over your base of support. Balance is successful because multiple systems interact flawlessly and automatically—coordinating, weighing, and modulating information from both the environment and the central nervous system. This involves both motor input and sensory feedback and is affected by disorders within those systems (muscle weakness, decreased range of motion, pain, neuropathies, and visual and vestibular disorders, among others).

1.12 Postural Control

Postural control involves postural stability (balance) and postural orientation. Postural stability or balance is the ability to maintain your center of mass over your base of support. Postural orientation is the ability to control the segments of your body in relation to one another and to gravity, taking into account the environment and whatever task is being performed.

Postural control requires the interaction of musculoskeletal and neural components. Musculoskeletal components include range of motion, flexibility, muscle function, and the biomechanical relationship between body segments. Neural components include: motor processes, which organize the muscles into neuromuscular synergies; sensory and perceptual processes, which integrate input from the somatosensory, visual, and vestibular systems; and higher level processes that contribute to anticipatory and adaptive aspects of postural control (Shumway-Cook and Woollacott, 2016).

1.13 Falls

Finding a simple description or definition for “fall” is a bit more difficult than defining balance and postural control. When we lose our balance, if it is severe enough we fall—to the ground, to a chair, onto a couch, or on top of a friend. If the loss of balance is mild, we generally don’t think of this as a fall—we simply say we lost our balance for a moment but quickly regained it.

Technically, a fall occurs when we are unable to maintain our center of mass over our base of support. In the picture below the center of mass is represented by a blue ball. In standing, the center of mass would be within the gymnast’s body. As she is completing a cartwheel however, her center of mass has moved well forward and outside her body. Whether she falls or not depends on several internal and external factors: her speed, the support surface, her strength, and her sensory awareness.

The center of mass/gravity (blue ball) is outside the body of this gymnast after completing a cartwheel. As the center of mass moves further outside the body the more likely that a fall will occur. Source: D. Gordon E. Robertson. Wikimedia Commons.

Researchers, clinicians, and caregivers often describe falls differently than people who have fallen do. For example, a 92-year old retired nurse recently fell in her garage. Her daughter, a physical therapist, found her sitting next to the washing machine, struggling to rise from the cement floor. When asked what happened, her mother said “I sat down on the ground.” When her daughter said “You lost your balance and fell” her mother angrily replied “I didn’t fall, I sat down.”

Disagreement about how to define a fall is not restricted to retired nurses and their daughters. A nursing assistant in a skilled nursing facility likely knows what a fall is but may be reluctant to report it out of fear of reprimand. A charge nurse may not want to do the extra paperwork required to document a fall. The facility operators or owners may not want to spend the money to repair unsafe equipment and, not surprisingly, an older adult may be reluctant to admit to a fall—perhaps considering it unimportant or fearing the consequences.

To learn more we turn to professional organizations, researchers, government agencies, and consensus groups. Many of these organizations have useful definitions for falls, assisted falls, and accidental falls.

The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI) is a patient-safety and quality improvement program that provides data to participating hospitals and conducts research on the relationship of nursing care and patient outcomes. NDNQI defines a patient fall is “an unplanned descent to the floor (or extension of the floor, such as a trash can or other equipment with or without injury to the patient, and occurs on an eligible reporting nursing unit.” The NDNQI recommends that all types of falls be included, whether they result from physiologic reasons (fainting) or environmental reasons (slippery floor).

NDNQI also addresses a well-known gray area—the “assisted fall,” which they describe as: “a fall in which any staff member was with the patient and attempted to minimize the impact of the fall by easing the patient’s descent to the floor or in some manner attempting to break the patient’s fall. A fall that is reported to have been assisted by a family member or visitor does not count as an assisted fall”.

The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing (HIGN), the geriatric arm of the NYU College of Nursing, is a leading advocate of interdisciplinary solutions to falls in older adults. HIGN defines a fall is “an unexpected event in which the participant comes to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level.” They consider falls to be a geriatric syndrome, the result of pre-existing and precipitating factors (HIGN, 2012).

Clinicians Ann Shumway-Cook and Marjorie Woollocott offer a practical clinical definition in their book Motor Control: Theory and Practical Application. A fall is “an unplanned and unexpected contact with a supporting surface” (Shumway-Cook and Woollacott, 2016). In this definition a supporting surface can be the floor, a wall, a chair, a bed, or another surface that is used unexpectedly to aid recovery of balance.

A culture of safety is necessary to decrease falls and risk for falls among older adults, especially nursing home residents. A culture of safety is dependent upon leadership; it is pervasive and permeates through a facility, affecting how care is provided. A positive safety culture has a significant impact on a resident's care experiences as well as the experiences of staff. It enables greater transparency, better communication, and greater awareness of patient safety risks. Communication among the interdisciplinary team members about each fall in a facility is critical to maintaining a culture of safety as is a positive leadership style among supervisors (Resnick and Boltz, 2023).

There are a number of components that are essential to establishing a culture of safety. They include teamwork, nonpunitive ways to address errors that do occur, effective leadership, and appropriate staffing rate and mix of staff. While recent federal reforms are targeting improved standards for nurse staffing, currently there are no clear guidelines on staffing requirements or mix of staff. There is some evidence that suggests that when there are more licensed nursing hours per day at a facility (i.e., hours worked by registered nurses or licensed practical nurses) falls with injuries among residents tend to decrease (Resnick and Boltz, 2023).

Back Next